Editors Note: APF Reporter Vol.11 #3 exsisted only as a photo copy, becuase of this the pictures in this story are of poor quality.

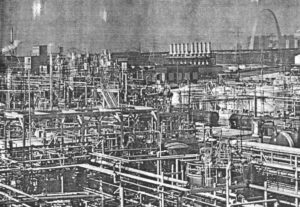

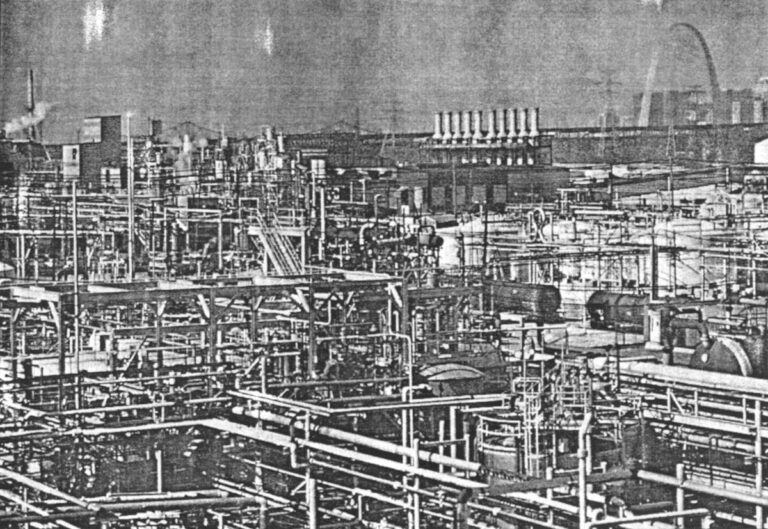

Monsanto Company’s three St. Louis area plants use perchloroethylene to make a bacteria-fighting chemical in deodorant soap, produce paradichlorobenzene to make mothballs and use chlorine to make swimming pool chemicals. In the process, the plants discharged 4.4 million pounds of these and 28 other hazardous chemicals into the air last year.

The company recently filed the emissions numbers with the Environmental Protection Agency in response to a sweeping new federal law that has the potential to revolutionize what the public knows about the toxic chemicals released by American industry into the air, water and land around them.

Perchloroethylene in high doses can cause dizziness, even death. It can endanger an unborn baby or pose a threat of cancer. Paradichlorobenzene is an irritant that at high levels can cause liver and kidney damage. It also causes cancer in laboratory animals. Chlorine overexposure can cause nausea, pain to eyes, nose and throat, coughing and even death.

But what health and environmental risks, if any, do they pose at the low levels routinely wafting into communities beyond the plant boundaries? What is the potential for accidental release at higher levels and how can this be prevented? What is being done to plan for emergencies, should they occur? To what degree can routine emissions be reduced?

Business leaders, elected officials, civil servants, scientific and medical experts, community and environmental activists–and ultimately the public–are being forced to confront a host of challenging questions as a federal law, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act of 1986, goes into effect.

The law requires that, for the first time, information on more than 1,000 hazardous chemicals stored and released, both accidentally and routinely, be made available to the public through local, state and federal agencies. An estimated 500,000 to 1 million facilities–and eventually several million–are affected by its provisions.

“The law will reveal to the public how pervasive chemicals are in our environment,” said Michael Stahl, acting director of EPA’s Toxic Substances Control Act assistance office. “The public reaction will range from hysteria where none is warranted to apathy in the face of data where hazards do exist.”

It “gives citizens an unprecedented opportunity to learn about substances in their environments and to use that information to affect decisions about those substances,” says Susan Hadden of the University of Texas’s LBJ School of Public Affairs. “It is a law of the computer age. There will be so much information that no human being could grasp it.”

A key deadline came July 1. An estimated 30,000 facilities were required to report to EPA and state agencies on total annual emissions from a list of 328 hazardous chemicals. A novel feature of the law ordered EPA to make the information available through a computerized toxic chemical inventory, accessible to anyone with a personal computer. This is not expected to be working until early 1989.

A sampling of initial reports provided by industry shows that large, often staggering, amounts of toxic substances are discharged into the environment by almost every type of business, large and small.

The industries say the emissions are legal, meeting or falling below existing laws. But environmental critics say those laws have too many loopholes. Many toxic chemicals, particularly those going into the air, are not specifically regulated at all. Others are subject to rules that require permits or “best available” technological controls that reduce but do not eliminate the release of chemicals into the environment.

A benchmark of the emergency planning provisions of the law was an October 17 deadline for completion of emergency response plans by newly constituted local committees around the country.

Proponents of the law say it will force changes in the way industry does business, putting new local and national pressures on companies known to have high emissions or store large amounts of chemicals with high accident potential. At the same time, they plan to use the data to help launch a grassroots groundswell for tougher environmental laws.

Sen. Frank R. Lautenberg, D-N.J., who helped craft the law, recently characterized it as the “right-to-know about poisons being dumped into the environment.” He and others hope it will galvanize congressional action on strong new air toxics revisions to the Clean Air Act, which is currently undergoing a heated congressional reauthorization.

House sponsor Rep. James Florio, D-N.J., goes even further: “People for the first time can make polluters accountable by forcing them to make their operations safe. But what really excites me about the right-to-know concept is my strong belief that people won’t stop there.…I think that newly empowered citizens will start pressing for results on a host of other pollution problems that still plague our country. Acid rain, ozone depletion, risks from garbage incinerators, and other problems still need to be dealt with and the effort to do that can benefit from the springboard of right-to-know.”

Government and industry, increasingly nervous about how the upcoming deluge of complicated raw data will be used, have launched their own campaigns to influence the inevitable debate. They warn that the raw emissions numbers, however large, have little meaning in public health terms. But they fear that the figures will further confuse, frighten or even numb an American public already overwhelmed by the array of toxic health hazards publicized over the past decade.

A May, 1987 EPA internal planning document warned of “inevitable confusion” when emissions data are released, with the numbers “highly susceptible to misinterpretation and misunderstanding…. If this information explosion results in major citizen anxiety, EPA is likely to be held responsible, and additional EPA efforts and/or congressional action may be demanded.”

“We’re at a flash point in our relations with our neighbors and it’s important that we get off the defensive and go public in a way we never have before,” said Union Carbide Chairman Robert D. Kennedy. In a meeting last year on the law, he urged industry managers to go “in the community, working the crowd, preparing them to receive information they won’t like…”

“I am not talking about teaching the public to love chemicals. I am talking about helping people to understand the stream of new information…. One reason to communicate the facts up front is that it buys the opportunity to talk sense to the public about chemicals. To tell them about safeguards installed and improvements made. To put risk information in perspective,” he said.

Otherwise, warned Kennedy, the “information is bound to surprise and no doubt frighten some folks…. Frightened, angry people will demand action.”

The law, technically known as Title III of SARA, the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986, passed in the wake of the December 3, 1984 chemical catastrophe at a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India that killed at least 2,500 and injured some 200,000 more. A smaller release at Union Carbide’s Institute, West Virginia plant fueled concerns about whether a major accident could happen here.

Although it was dubbed “Bhopal’s baby” by some, the community right-to-know provisions of the law reflect a movement that began in the 1970’s with efforts to provide workers with the right-to-know what chemicals they were exposed to in the workplace and expanded to include community right-to-know. Some 30 states and numerous localities have passed chemical right-to-know laws.

The federal legislation has four major provisions. It requires state and local efforts to develop emergency response and preparedness capabilities. It requires immediate emergency notification to state and local authorities of releases of chemicals designated “extremely hazardous.” It requires submission of inventory lists involving certain chemicals to local and state emergency planners and local fire departments, including estimated amounts stored at an individual facility. And it requires an annual inventory of chemical releases to be filed with EPA and the states.

It is so ambitious as to be necessarily flawed. “It has too many purposes,” says the University of Texas’ Hadden. “There is a gold mine of data, but we don’t know how to make use of it yet.”

Many companies have missed deadlines and compliance appears to be low. Response to deadlines for reporting on the storage of extremely hazardous chemicals, accidental release of chemicals and safety data to state and local authorities was estimated to be well under 50 percent.

Although many large chemical companies have devoted significant time and money to complying with the law, accompanied by pledges to voluntarily reduce their emissions further, many companies don’t even realize the law affects them. The paperwork burden is enormous: facilities might have to make five different kinds of reports under Title III.

While the national focus has been on the yearly discharge figures, local efforts in emergency planning have been underway. Last year, according to EPA figures, more than 28,000 chemical releases of all types occurred in the United States.

More than 50,000 people in some 4,000 planning districts nationwide are expected to serve on Title III -local emergency planning committees, aided by another 100,000 local fire employees, city officials and industry representatives, according to David Speights, chief of emergency preparedness in EPA’s Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response. But he estimates that only about half of the local emergency planning committees will meet the October deadline for completing their initial response plans.

Many local and state governments are overwhelmed with the complex law’s requirements and have little money to process the data and make it accessible to the public, let alone monitor what industry is doing.

Hampered by limited resources, EPA has stuck to carrying out the letter of the law and has come under attack from all sides for not doing enough. Title III is set to get only $17.8 million of EPA’s $5.1 billion budget for fiscal year 1989, with most of the resources targeted to getting the computer database working.

Industry complains that the government needs to provide better health information to put the raw emissions numbers in perspective. States say they need more help from the federal government. And congressional sponsors and environmental groups question how prepared or committed top EPA political officials are to carrying out the spirit of the new law.

Despite predictions of public uproar, there has been remarkably little reaction to the new law to date, in pan because access to the figures through government agencies is still extremely limited and media coverage has been sparse.

Nonetheless, even critics like Fred Millar, of the Washington-based Environmental Policy Institute, say the law is starting to make a difference. “The law is working. It has laid a base for what can be done next year. Even if only half the committees are working, we’re way ahead of where we were before. This cannot help but improve chemical safety. I’m optimistic that what we can accomplish will be substantial.”

Until the federal computer program gets underway, the dimensions of annual chemical emissions data are difficult to define. Some companies voluntarily have shared their emissions numbers with local communities in which plants are located or responded to outside inquiries before the information becomes available from the government.

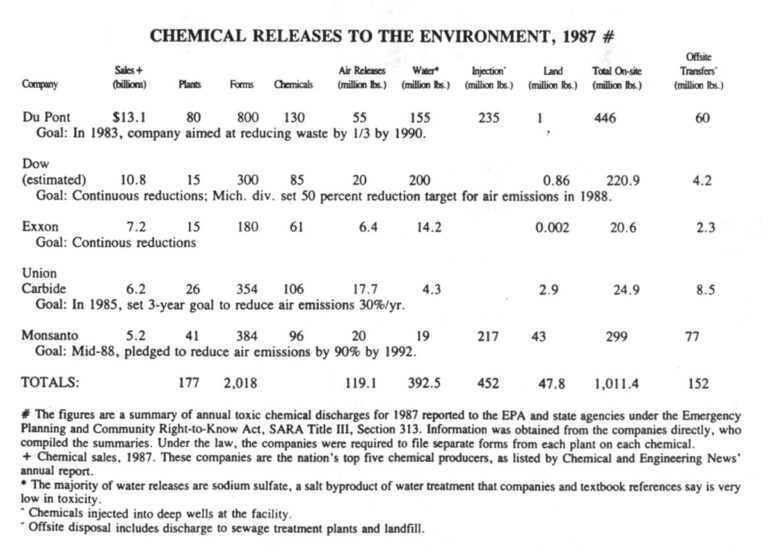

Data gathered from the nation’s top five chemical producers give a glimpse of the magnitude of chemical releases, as well as the problems in deciphering what threats, if any, they may pose. Lumped together, the five companies estimated releases of more than one billion pounds of chemicals to the environment. This includes chemical releases of 119 million pounds to the air, 392 million pounds to the water, 452 million pounds to underground wells and 48 million pounds to the land in 1987-from 177 plants across the country.

A summary:

At Du Pont’s Belle plant in West Virginia’s chemical-producing Kanawha Valley, 1.4 million pounds of chemicals went into the air and 4.5 million pounds to the water last year. The 31 reported chemicals included everything from quick-acting toxics like sulfuric acid to cancer-causing chemicals like formaldehyde. Du Pont, ranked number one with $13 billion in chemical sales last year, submitted about 800 reports from 80 plants and refineries for a national total of about 55 million pounds to the air, 155 million pounds to the water, 235 million pounds to deep wells and 1 million pounds to the land.

Dow Chemical Company’s plant in Midland, Michigan reported annual emissions of 5.5 million pounds of chemicals under the law, 70 percent of them airborne, 26 percent to the water and 3.7 percent to Dow’s licensed landfill. About half of the air emissions involved methylene chloride, a controversial chemical suspected to be a carcinogen. Nationally, based on 300 reports from 15 facilities, Dow estimated that its 1987 emissions totaled about 20 million pounds of chemicals to the air, 200 million pounds to the water and 860 thousand pounds to the land.

Fifteen plants of Exxon Chemical Americas submitted 180 reports on 61 chemicals totaling about 6.4 million pounds to the air, 14.2 million pounds to the water and less than 2,000 pounds to the land.

Union Carbide said that it released 1.7 million pounds of chemicals to the air, 4.3 million pounds to the water and 2.9 million pounds to the land at 26 locations, the largest in New Jersey, West Virginia, Louisiana and Texas. It filed 354 reports on 106 chemicals.

Nationwide, St. Louis-based Monsanto estimated it released about 20 million pounds of chemicals to the air, 19 million pounds to the water, more than 43 million pounds to the land and injected 217 million pounds into underground wells.

These numbers are just the tip of the iceberg. Although widely perceived as targeting the chemical industry, the law’s tentacles extend to “virtually all manufacturers in the country using chemicals who would never have thought of themselves as chemical companies,” noted Charles Elkins, director of EPA’s Office of Toxic Substances.

The initial cutoff for submitting toxics inventory data included facilities with 10 or more full-time employees that manufactured or processed any of the listed toxic chemicals in excess of 75,000 pounds each year or used them in amounts over 10,000 pounds.

Electronics companies, soft drink bottlers, sporting goods suppliers, car manufacturers, building supply producers, even companies like the Arctic Ice Cream Novelties company in Seattle, Washington were among those submitting the complicated federal form R’s to EPA by July 1.

EPA originally estimated that it would receive 300,000 emissions reports, based on an average of 10 reports at five pages each from 30,000 facilities. But, according to EPA’s Charlie Osolin, as of late September, only about 70,771 forms from about 17,200 facilities had been received at the processing center. While individual companies were filing fewer reports each, it still appears that a large number of firms aren’t following the law and are subject to penalties of up to $25,000 a day.

Located on the seventh floor of the L’Enfant Plaza East office complex in Washington, the EPA processing center includes a public reading room where access to paper copies of requested individual reports was expected to be available starting September 1.

EPA has arranged to have the data computerized through the National Library of Medicine. When the federal computer system is up and running, anyone with access to a computer could theoretically assemble emissions data on a given plant, a given chemical, a local area, state or even on the country at large. Companies could be compared to one another in terms of their releases of different chemicals and environmentalists might have new ammunition for a “dirty dozen” list.

Because such information has never before been gathered on such a grand scale, it is likely to locate new hot spots for further study and pour fuel on the fire in communities where there are already environmental health concerns. Real estate agents, some speculate, might even use the data to evaluate property values.

“My vision is that there would be a computer in the public library that was very user-friendly,” said the University of Texas’ Hadden. She is concerned that there are still lots of barriers to getting information to the public in a usable form.

The federal computer system applies only to the annual emissions data. There is no uniform system for handling data submitted directly to states and local communities, she noted.

Hadden surveyed citizens in New Jersey and Massachusetts who had attempted to use state right-to-know laws and found “the thing people talked more about than the information they got was the difficulty they had in getting it. They were entitled to get it. But they didn’t know how.”

EPA’s Osolin said that the agency is considering ways to make the data available even without a computer. It plans, for example, to do a microfilm readout of the emissions information for each state and put it in at least one public library in each county, he said.

Given all the attention to the enormous logistical challenge of assembling the emissions data and making them public, there has been less attention to the more basic and difficult question: What do the numbers really mean?

Raw numbers, ones that estimate gross annual emissions into the environment, by the pound, are required under the law. Environmental groups urged EPA to go further, saying the information would be more meaningful if industry were required to provide more precise information about the timing of these releases. Several major “peak releases” of high levels of chemicals would have different health consequences than a slow but steady stream of chemical releases over the entire year.

In developing the regulations, EPA chose the simpler path. Several EPA officials called this a major shortcoming, with one noting that concern about reaction from the White House Office of Management and Budget and industry pressure had influenced the decision. They said that the agency still was planning to come up with more detailed emissions reporting requirements in the future, but this has fallen behind schedule.

The existing lump sum emissions numbers are easily subject to misleading conclusions if judged alone. Emissions levels alone do not mean human exposure, let alone known human health hazards.

EPA’s Elkins noted that 50 tons of emissions from one plant and 100 tons from another does not mean that the second poses twice as great a problem. Instead, translating the emissions data requires additional knowledge about the toxicity of the chemicals involved and the degree to which the chemical releases are likely to expose human populations.

Several chemical companies cited their water discharge numbers, saying that while the amounts were large, a majority–more than 90 percent in several cases–came from one compound. It is sodium sulfate, a salt that results from water treatment. They say it poses little risk and should be removed from the EPA toxics list.

Among the relevant questions: Does the chemical of concern pose acute (short term) or chronic (long term) health hazards? How potent is it in causing damage, as a small amount of a highly toxic chemical can be far worse than large amounts of a less hazardous one? How extensively have the health or environmental effects been studied? How long does it remain in the environment? Which way does the wind blow from the plant? How many people live close to the plant?

To assess potential human exposure requires computer modeling or actual field measurements to project the path and concentration that chemicals will take once they are released from a plant, information that is difficult to obtain unless individual companies do the studies and make them public. The possible exposure levels should then be compared with known toxic levels.

A major benefit of the new law will be to “find out what people don’t know. It’s a question of identifying the gaps,” said environmental activist Millar. He says that people will be “shocked” not only at the large amounts of chemicals going into the environment, but “at how little actual monitoring of air emissions there is. Nobody really knows where the stuff goes.”

He believes that Title III will “boomerang on the chemical industry,” reversing the burden of proof for those who say, “as far as we know it’s not causing any harm.”

There are concerns about the quality of the data provided in the first year. While large chemical companies have the technical capability to provide better estimates, smaller ones have more difficulties in doing so. An early analysis of the first annual emission forms revealed a high error rate in just filling them out properly.

EPA is preparing a risk screening guide to help decision makers evaluate the seriousness of discharges and plans to distribute chemical fact sheets to the states based on information earlier gathered by the state of New Jersey for its worker “right-to-know” program.

In addition, EPA has launched its own pilot project to see how the emissions data can be used with the best available scientific and decision-making tools to do risk assessment for specific communities.

But there are still severe limits on the available health effects information. EPA’s Osolin said that the agency currently has substantial health information on 235 of the 328 chemicals on the toxic inventory, some information on 43 and limited information on 50. But even for chemicals on which health information has been assembled, few have been scientifically evaluated on a rigorous basis, particularly in terms of chronic exposure at the low levels found in the environment.

Despite the limitations, availability of the emissions numbers will inevitably start a new debate about chemical safety. In the opening round, several companies, following earlier industry advice from the Chemical Manufacturers Association, a trade group, have taken the first opportunity to present their own interpretation of the emissions numbers, largely unchallenged.

A common industry approach appears to be one of reassuring the public that the existing emissions numbers, while large, pose virtually no health or environmental risks. Nonetheless, companies are pledging to step up efforts already underway over the past decade to reduce the emissions and build on earlier emergency planning efforts.

Monsanto was among those that took the lead, launching an open and aggressive effort to present its story to the St. Louis community. While technical experts were preparing the emissions numbers, just as much attention was paid to the communications strategy the company would pursue.

More than a year of preparations were made–putting together informational materials, slide shows, videotapes and test-marketing with community “focus groups”–culminating in a series of extensive briefings to the employees, community and press in late June, just before the reporting deadline.

The presentations outlined in detail the large total annual amounts of chemicals being released into the environment, but stressed that the company’s computer projections found the chemicals that reached the community to be very low. It projected, for example, that concentrations of paradichlorobenzene, the mothball chemical, in the community around its Krummrich plant would average only 0.00003 parts per million in the air, with a high of 0.005 per million. (Federal limits are 75 parts per million during an 8-hour shift).

But the company softened potentially bad news–large emissions totals–with good news–a pledge to reduce air emissions by 90 percent by the end of 1991. “The best scientific and medical data available indicate that the emissions we are reporting do not pose a health risk in our plant communities. However, the public expects no less than a maximum effort to reduce emissions, nor should we,” said Monsanto chairman Richard J. Mahoney.

“We felt we have to be very pro-active. We needed to be out there disclosing our emissions numbers. A lot of other companies are going to file the forms and hope it all goes away,” said Glynn Young, manager of environmental and community relations for Monsanto.

The company’s strategy apparently paid off in the early returns. St. Louis and Chicago papers headlined Monsanto’s promise to cut back emissions and rather than “mass hysteria” at the community briefings, Monsanto officials encountered few questions, said Young. “The reaction was kind of underwhelming. Over time…it may change.”

“In my humble opinion, it’s the best law that ever happened to the chemical industry,” said Monsanto’s Young. “People are going to find out this is a very chemically dependent society. It may raise a lot of concerns in the short run. But in the long run it will help people get a better perspective.”

Roger Pryor of Missouri’s Coalition for the Environment, said, “My concern is an overload of information here. The real purpose was to give the public usable information so they can make intelligent choices about the risks they may be facing. Unless this is interpreted the public will be at a loss to understand it.”

While crediting Monsanto with setting an example for other industries, Pryor is concerned about the ability of outside groups and state and local government to provide their own interpretation of the numbers. “We don’t have the analytical capability to do it ourselves.”

“We are not able to cope. There are no resources,” said Dean Martin, environmental emergency response coordinator of Missouri’s Department of Natural Resources. “We don’t have the ability at this time to evaluate the significance of that data. We have file cabinets filling up. We have no idea what it means.”

Martin, who must oversee not only the emissions data but the emergency planning under Title III, has only temporary clerical help and two unfilled state positions. “I think we need, within a couple of years, 15 to 20 people,” he said. “This is something that is needed badly.”

But neither EPA nor industry will have the last word in shaping public reaction to the law.

Concerned that industry was getting a headstart in presenting its side of the story, Deborah Sheiman of the National Resources Defense Council sent out a press advisory as the July 1 deadline approached. She outlined more than 50 tough questions to ask industry and the government about the new emissions numbers to put them “into perspective,” warning that “industry will make a great effort to characterize their toxic releases in a favorable light.”

Sheiman’s own counterattack, however, went to the other extreme, referring to a “witches brew of hundreds of toxic chemicals” that are “spewed into the air, pumped into waterways and dumped onto the land. Toxic chemicals like these can cause cancer, birth defects, nervous system damage and other killing and disabling diseases.”

At the local level, among the first environmental groups to raise questions about the Title III data was the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition in San Jose, California. It held an August 2 press conference, charging that industry was using the air as an “open sewer” and calling for waste reduction targets similar to those set by Monsanto. The group calculated that 12 million pounds of 34 different chemicals were being discharged by 25 area companies, including a “Silicon Valley Dirty Dozen” that included Hewlett Packard, IBM, Lockheed and other high-tech electronics and defense firms.

Local companies counterattacked, accusing the toxics group of distorting the numbers and mixing apples and oranges by lumping air releases with unrelated off-site waste transfers. “The way the data was mischaracterized was just terrible,” said Gary Burke of the Santa Clara County Manufacturing Group. “The coalition is using those numbers to create fear and anxiety for their own purposes.”

The new emissions information can also pose potential problems for companies already under scrutiny because of existing environmental concerns. In Rochester, N.Y., for example, Eastman Kodak Company was rocked by questions earlier this year about possible chemical contamination of bedrock and ground water at its major film manufacturing plant and allegations that it had failed to notify the surrounding community about potential leakage.

The company went ahead with planned early announcements of Title III data showing that in the Rochester area it was releasing some 26 million pounds of 64 chemicals into the environment, mostly into the air, including 9 million pounds of the same suspected cancer-causing agent, methylene chloride, that was detected underground.

The news was particularly upsetting to some in the immediate neighborhood, said Joe Polito, of Concerned Neighbors of Kodak Park. “I’m more concerned about the air,” he said, adding he is moving out of town to a nearby suburb. Kodak has set up a financial incentives plan to stabilize local housing.

By and large, says Kodak spokesman Ron Roberts, “the pot was boiling enough” that the air emissions information was overshadowed by the original underground pollution publicity, but did heighten overall concerns. “People in this area generally didn’t consider Kodak a chemical company. We were a film company,” noted Roberts. Now, he says, the company “has really tried to go public, if there is any question….We still feel the alarm is for no reason.”

Nationally, after a summer in which environmental issues once again became front-page news, from polluted beaches to the hot climate, the Title III data may attract even more attention in the months to come.

Despite the seriousness of the toxic chemicals debate and the advance preparations by all sides, Title III does not necessarily a story make.

Consider the experience of chemical companies in Port Arthur, Texas who sought to be among the first to present their toxic emissions data last June to the public. After briefing public officials, they found themselves faced with a press luncheon almost devoid of the eagerly anticipated reporters.

Where had they gone? According to the University of Texas’ Hadden, a speaker at the briefing, the hottest story in town was a more immediate environmental threat: The United States Forest Service had gone to court over plans by the Rainbow Family of Living Light to camp in east Texas over the Fourth of July holiday weekend. Some members of the ’60’s-style group, thousands of hippies strong, reportedly cavorted in the nude in past holiday happenings.

Industry “gave a party and nobody came,” said Hadden. “Do you think if we took our clothes off the press would come and hear about hazardous chemicals?”

©1988 Cristine Russell

Cristine Russell, on leave from The Washington Post, is reporting on the risks of everyday life.