Editor’s Note: We’re pleased to publish an excerpt from David Lamb’s latest book, “The Arabs: Journeys Beyond the Mirage,” which will be published by Random House in February. It is a product of his writing and research during his APF year.

In the blissful still of early morning, when Cairo is bathed in the soft blue of desert dawn and the Nile’s waters are smooth as silk, I could see from my balcony the vestiges of beauty in a city that was once among the grandest and most important on earth. Unlike the new, sterile Arab cities built by oil money, Cairo has soul and substance. Its streets throb with life, its neighborhoods are distinct and vibrant, its open-air cafes are crowded until the late hours of the night with men who discuss everything from the cost of bread to the price of peace over countless cups of sweet, thick coffee. In many ways, Cairo is to the Middle East what London is to the English-speaking world: it is an emotional magnet, a place where an Arab has only to step off the plane to know immediately that he is home. Home to his history, his religion, his identity.

The word for this thousand-year-old city in Arabic is Al Qahira, which means victorious. On the southwestern edge of the metropolis are the three Great Pyramids of Giza. On the northeast is an obelisk that marks where, according to legend at least, Plato once studied. The French that Cairo’s elite still speak is a reminder of Napoleon Bonaparte’s scientific and military expedition here two centuries ago. And the architecture–the Romanesque stone doorways, the sand-colored mosques, the wrought-iron balconies reminiscent of Paris, the mullioned windows and the domes of the Mamluks, all darkened with age-is a reminder that Cairo remains a juxtaposition of new and old, of East and West.

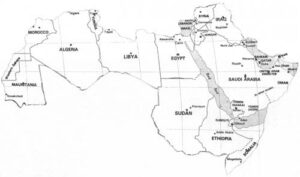

No other city dominates its continent the way Cairo does Africa. It is four times more populous than Africa’s next largest city (Lagos). It is the intellectual, religious and educational seat of the Arab world, and even the Arabs’ displeasure with Anwar Sadat’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel did little to diminish the importance they attach to Egypt and its capital. More films are produced in Cairo, more books published, more newspapers read than in any African or Arab capital. An intelligentsia provides lively and thoughtful debate, and foreign policy emanating from Cairo plays a crucial role in shaping the history of the Middle East. If you drew three circles, as Gamal Abdel Nasser used to do, one each around the Arab, Islamic and African nations of the world, the lines would converge very close to Cairo.

Yet it was never easy to know whether Cairo–and indeed Egypt as a whole–belonged to the First or Third world. After all, how can you speak of civilization’s birthplace as being a “developing” nation? Yet never have I seen a place where the past seemed so distant and irrelevant, the present so unmanageable, the future so unimaginable, for time has not been kind to this shabby old dowager. Yesterday’s grandeur has become today’s urban nightmare. The capital is sinking under the weight of people, people and more people–14 million of them at last count–and Egypt itself seems in danger of becoming a Bangladesh on the shores of the Mediterranean, an impoverished land gripped by lethargy and decay, its illiterate population growing by more than a million people a year, its daily bill for imported food already at $10 million.

Wandering the streets of Cairo, poking through the dark alleyways that smell of urine and are strewn with trash, you can stumble on dilapidated villas where orchestras were heard in the gardens of summer evenings long ago. Handsome Victorian-era apartment buildings stand mirage-like amid rows of tenements, their wrought-iron balconies draped with laundry, their shutters drawn tight against the assault of noise and dirt. Broad boulevards lead into expansive squares that hint of Paris; narrow alleyways that are scented with spices and crowded with goats and black-veiled women wind through mysterious, ochre-colored worlds, almost Biblical in tone and texture.

A City of Banyan Trees

Sometimes on the dusty shelves of unlit bookshops, you can find old guidebooks to a city that is no more. They speak of Cairo’s fine opera house, of banyan trees and patches of green that stretched along the verdant promenade of the corniche clear out to the suburb of Maadi, of the splendidly pampered Japanese garden in Helwan and the excellent restaurant in Groppi’s downtown pastry shop, of days when Cairenes could live and breathe and move easily in what contained, until the 1950s, among the last of the twentieth-century, Westernized enclaves in the Arab world. Cairo, in fact, was really two cities throughout most of the 1800s and 1900s: There was the Cairo for Europeans and the Egyptian aristocracy with manicured gardens, elegant hotels and palaces, fine carriages and well-dressed people, and farther back from the Nile, past the parks and villas, there was the crowded, dirty Cairo for everyone else.

On the day that I was to discuss the decay of Cairo with Hassan Fathi, Egypt’s internationally acclaimed architect, the local papers carried three items that caught my attention: Two apartment buildings had collapsed killing seventy people; a pedestrian had fallen into an uncovered manhole and drowned in raw sewage; and a student had jumped to his death from a bridge after being tormented for months by his neighbor’s blaring radio. He had left a note that said, “Suicide is better than life without dignity.”

Fathi’s creative urban designs had been used in projects from Europe to the United States, his ideas for low-cost housing had been put into practice in India. But in Cairo, where he advocated the construction of satellite cities in the desert, no one paid much attention. It was his great sadness that the people, his people who needed him most, had utilized his genius the least.

Thin and hard of hearing, Fathi was an old man when I visited him. He lived in one of the oldest parts of Cairo. in a rambling apartment full of maps and drawings and books written in English, French and Arabic. Every afternoon he observed the ritual of tea, making sure that each of his twenty cats shared his biscuits. He was, like almost every educated Egyptian I met, gracious and kind and forthright with both his opinions and his hospitality. From the street below his open windows the din of blaring horns and raised voices swelled up, making it necessary to carry on our conversation in shouts.

“What is happening to Cairo is a tragedy, really,” he said, cupping his hands to his mouth. “For forty years I have been fighting to save my city, and I have had no results. No one listens. Does anyone care? I’m not sure. Just look at those TV ads the government is running, then tell me I shouldn’t grieve for Cairo.”

The government’s television campaign he mentioned was intended to bring a little order to Cairo, an undisciplined city whose population generally ignores all traffic regulations, most standards of sanitation and many rules of good neighborliness. The campaign consisted of several one-minute spots interspersed throughout soap-opera dramas. In one, a popular actor walks under a building and is suddenly splattered with garbage dropped from an upper apartment. Wiping the goo from his face, he asks: “Is that what our country has come to? Egyptians, say it isn’t so!”

Alas, though, it is. An apathetic public, economic mismanagement and a wildly out-of-control birthrate have become the cancers of Cairo, sapping its strength and leaving its dazed inhabitants the victims of what is known in Egypt as the IBM syndrome–inshallah (if God is willing), bokra (tomorrow) and malesh (never mind). It doesn’t matter what gets done or how it’s done. If not today, then tomorrow. God decides anyway, so why worry? This sense of fatalism takes all responsibility out of human hands and puts everything from the outcome of wars to the keeping of appointments under the control of a Greater Power. That Cairo is being transformed into a vast slum of rural peasants, attracted to the city by the illusions of a better life, does not greatly concern the individual Cairene because, the reasoning goes, man does not really control his destiny or his surroundings.

A generation ago, when Egypt produced a hundred or more feature films a year, Cairo’s thirteen first-run movie theaters were as grand as any in London. There was not a filmmaker in the Arab world who had not studied in Cairo, not a successful actor or a songstress whose fame was not dependent on the acceptance of the Cairo audiences. Today no first-class theaters are left. And in the flea-ridden theaters still operating, the seats are broken, the air conditioners don’t work, the aisles are littered with trash, and the audiences are made up almost exclusively of sexually repressed young men who hoot and holler in excitement when an actor and actress seem ready to touch.

“Our films used to change every week back when Cairo was the Hollywood of the Middle East,” said Salah Abou Seif, a prominent director. “Opening night was really a gala occasion then. It was Monday at the Royale, Tuesday at the Metropole. Everyone wore tuxedos and gowns and the papers reported the next morning who had sat in what box and who had worn what. A fine era it was.”

“The audience that used to support the first-class theaters just doesn’t exist any more,” said one of Egypt’s widely known character actors, Salah Zoufoukai. “Now, it’s a peasant society. My wife said the other night that she wanted to see a particular film that was playing in Cairo. I said, ‘OK, I’ll bring it home on video cassette, as long as you don’t make me go into the theater.’ Besides, who’s going to go out into the traffic if you don’t have to?”

At every major intersection fifteen or twenty illiterate policemen in soiled-white, ill-fitting uniforms stand frantically blowing whistles and waving their arms, trying to unsnarl traffic jams they themselves have created. But the drivers pay them no heed, for Cairo’s roads are an anarchist’s delight. “We have complete democracy here–you can do whatever you want,” a cab driver chuckled as he bounced over a median divider and headed up a one-way street, the wrong way. Not to worry. Speed limits and safety restrictions are seldom enforced–a twenty-five-cent bribe will pacify most uncooperative policemen–and the only rule-of-the-road is that he who honks loudest with the largest vehicle has the right of way.

Undeniably, though, lives were saved when Cairo’s unruly drivers were immobilized by traffic jams of classical proportions, because the city’s accident rate–eighty fatalities and six hundred injuries per 10,000 vehicles–is the highest in the world, according to a World Bank study. At that rate, the United States’ traffic toll would be 1.3 million dead and nearly 10 million injured every year. The former American ambassador, Nicholas Veliotes, used to peer out at the long lines of motionless cars blocking every intersection in sight and spring from his bullet-proof limousine with the words, “The hell with it. Let’s walk.” And off he would head for his next appointment, jacket slung over his shoulder, followed by his Egyptian bodyguards.

Cairo’s deterioration is of more than passing interest because the conditions that have allowed it to happen were largely avoidable. Yet throughout the Third World, dozens of cities are becoming the Cairos of tomorrow, buffeted by the same forces and awaiting the same fate. At some point even creative urban planning becomes irrelevant and new overpasses to move the traffic and new apartments to house the poor represent not much more than a finger in the dike of a city where housing shortages have forced more than 1 million people to stake out residency in cemeteries.

The first force of destruction was government centralization. Everything is centered in Cairo. If an Egyptian needs a new passport or has a question about his war pension, he must come to Cairo. Industry, government, education, commerce and diplomatic missions are all centered here. One in four Egyptians lives here. Cairo, in fact, is Egypt and nothing of significance happens anywhere else in the country. Appropriately enough, the Arabic language uses the same word for both Egypt and Cairo, Misr.

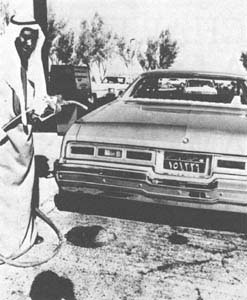

Then there was the constant state of hot and cold war between Egypt and Israel from 1948 to the mid1970s. Millions of peasants poured into the capital to seek safety during the ’67 and ’73 wars, and in the era of confrontation, the nation’s financial resources and its energies were channeled to the military, leaving nothing with which to save a city or build a nation. Every pothole in Cairo’s streets is a legacy of the conflict with Israel, every eyesore represents a decision to buy a tank instead of to repair a building, a sewer or a telephone system. Besides which, Egypt’s leaders never gave much thought to maintenance in the first place. They much preferred to spend money on grandiose projects that were flashy and new.

Compounding these problems were the policies of Nasser, Egypt’s president from 1953 to 1970. In a burst of socialistic enthusiasm, he destroyed the power of the upper class, instituted mass education and in the process reduced school standards to the lowest common denominator–and pushed through a series of rent-control laws that destroyed landlord profits. Suddenly it was no longer economically reasonable for an owner to repair an elevator, hire a janitor or paint a building. Some large offices in Cairo still rent for the equivalent of $25 a month. Not a piaster has been spent on the buildings for a generation, and more often than not, the elevators are dead, cobwebs cling to the ceilings and the trash that has accumulated in the hallways needs to be shoveled out, not swept.

And finally there is the birth rate–the number of births per year per 1,000 people. In Egypt, where a baby is born every nineteen seconds, the rate is forty, compared to just over fifteen in the United States and thirteen in Britain. Already the Arab world’s most populous nation, with 39 percent of the people living on the thin green ribbon along the Nile that constitutes only 4 percent of the land, Egypt will have a population of seventy-five million by the turn of the century. If the present trend continues, it will need nearly four million new housing units by the year 2000 and will have to import one seventh of all the surplus wheat in the world to feed its people. Cairo’s population is growing at the rate of a thousand a day-seven hundred new babies and three hundred arrivals from the countryside.

In Cairo’s most crowded districts the population density has reached 240,000 per square mile, which is tantamount to packing the entire city of Corpus Christi, Texas, into a single square mile. The United States has spent $67 million trying to help Egypt develop a family-planning program and has shipped in condoms by the carton, but to little avail; barely 25 percent of married Egyptians use any form of contraception (compared to more than 50 percent in Mexico, Taiwan and Colombia, three underdeveloped nations where family planning is working). Half the population is under age fifteen, and despite mass education, illiteracy is increasing, opportunities are decreasing. Every year 400,000 Egyptians enter the job market to compete for jobs that do not exist, and every year 40,000 students are graduated from the nation’s thirteen universities. Most find little meaningful employment and are forced to take jobs in government or to drive taxis or wait on tables. In the Ministry of Agriculture alone, there are two thousand Ph.D.s, the majority of whom sit at empty desks without telephones or typewriters or notepads. (Every university graduate is promised a government job, a policy started by Nasser; the bureaucracy as a result has grown from 370,000 to two million in three decades’ time.)

Although educated, financially secure Egyptians tend to have smaller families, the peasant majority still believes–with good reason–that large families are necessary to provide a financial safety net for old age. Some parents also believe it is their duty to promote the growth of Islam, a position religious leaders do not discourage even though Islam’s official policy on birth control is ambivalent. Even educated Egyptians see the empty desert all around them and, figuring it one day will be conquered by Western technology and made habitable, ask, “What population problem?”

For Egypt, though, the population explosion means that serious economic planning is impossible. “By the Prophet Mohammed,” President Hosni Mubarak said after getting a report on the nation’s economy, “if they brought in a government of angels, it wouldn’t make any difference.” And for Cairo, the explosion means that life will continue to be a burden of endurance for all but the very rich and that as the impoverished class becomes larger and more dissatisfied, the call of religious zealots for fundamental reforms in the system will have growing appeal. The scenario is a troubling one for everyone who has a stake in Egypt’s continued stability, including the United States.

Remarkably, though, Cairo, like most Islamic cities, has very little violent crime, and thefts even in the poorest areas of the capital are rare. Just as remarkably, the Egyptians never lose their sense of humor, no matter how desperate life seems. They joke constantly about themselves, their leaders, their lives, about everything except their religion. Their humor is a great safety valve for their frustrations, and without it, I doubt if Cairo could have survived to witness its second millennium of life.

©1987 David Lamb