The quintessential Arab is Goha, a man who lives in the fables and imaginations of the Arab world, and no where in the Middle East is there a figure more revered. He is lovable, eccentric, simple. His optimism is boundless, his generosity has no limits. He is said to be a fool, but he is clever and conniving and usually outwits every sultan he encounters. For the Arabs, Goha is the Walter Mitty of Arabia, the little man living out his fantasies, always triumphing over great odds. And for the Westerner, to understand Goha is to comprehend, to a small degree at least, the character of the Arab.

When the sultan wanted someone to teach his pet donkey to read and write, Goha volunteered. He said the task would take three years and to accomplish it he would need a villa with servants. The sultan agreed and next day Goha and the donkey moved into a splendid mansion. Time passed. Goha’s friends came to visit him and found him lounging about in great comfort while the donkey happily roved over the gardens. They warned him time and again that if he failed to come up with a literate donkey at the end of three years, he would surely lose his head. But Goha was unperturbed.

“I shall not give up hope,” he said. “After all, one of four things might happen: The sultan might die, I may die, the donkey may die or-who knows?–the donkey may learn to read and write.”

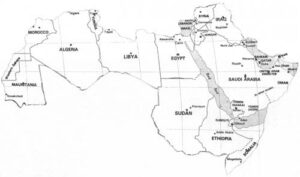

Goha is usually pictured as an old man with a white beard, a floppy hat and black robes. He is said to have been born in Iraq, though whether such a character ever really existed, no one knows. But Goha stories have been passed down through the generations from Syria to Morocco, and in the hearts of adults and children Goha lives today as the buffoon who proves himself more learned than the scholars, the bungler who knows that every problem has a simple solution, the good Samaritan who cheerfully gives street beggars the money his wife has advanced him for bread because the beggar’s need is greater.

Goha is usually pictured as an old man with a white beard, a floppy hat and black robes. He is said to have been born in Iraq, though whether such a character ever really existed, no one knows. But Goha stories have been passed down through the generations from Syria to Morocco, and in the hearts of adults and children Goha lives today as the buffoon who proves himself more learned than the scholars, the bungler who knows that every problem has a simple solution, the good Samaritan who cheerfully gives street beggars the money his wife has advanced him for bread because the beggar’s need is greater.

I like the Goha stories because they added a human dimension to the Arab character that one seldom saw portrayed in the West. If he had traded his robes for slacks and his mosque for a church, kids in the cornbelt of America or the villages of England would have understood exactly what Goha was all about. Yet to be different is often to be stereotyped, and when we are talking about Goha–or more importantly, the Arab–where is the common ground of mutual understanding that enables us to view them as people instead of as political cartoons?

Simply because he does seem so different to us–in dress, religion, language, culture–the Arab consistently has been judged by a double standard in the West. When he buys property in the United States, as Saudi Arabia’s minister of industry, Ghazi Gosaibi, pointed out in a Los Angeles speech, it is a minor scandal; when a non-Arab buys the same property, it is a sound investment. When an American acquires an expensive painting, he is considered cultured and refined; when an Arab does the same thing, he is decadent.

“You know, stereotypes cut both ways,” a Saudi prince, Sultan ibn Salman al Saud, mentioned one day as we sat in his office in Riyadh, talking about the negative image of Arabs in the West. “I remember once, when I was very young, my parents said that we were going to the United States for a visit. I said great, as long as it was Los Angeles or New York. But I told them I wouldn’t go to Chicago. Chicago really scared me. It thought it was full of gangsters and that people were getting killed on every street corner. That’s what TV had taught me.”

Salman, not yet thirty, was a bachelor, articulate and eloquent in his flowing white dishdasha, and as a member of the royal family, was presumably very rich. He was licensed to pilot executive jets, his father was a provincial governor, his degree was in mass communications from the University of Denver, where, yes, his classmates had kidded him about living in a tent and riding a camel. Unlike the political cartoons we in the West see of Arabs, Salman was refined and unassuming, with the build of an athlete and the good looks of a movie star. During our chance meeting in a government ministry he never mentioned anything about himself to make me think he was more than just another civil servant.

I didn’t hear of Salman again until I noticed his picture in the Los Angeles Times a few months ago. He was dressed in a Western business suit and would not have attracted a second glance on any street in America He had just become the first Arab to travel in space, having helped launch a telecommunications satellite, owned by the Arab League, during the eighteenth mission of the shuttle Discovery. The prince, who was headed to Washington to meet President Reagan in the White House, told the Times reporter how the mission had given him a sense of a world community. How foolish it seemed, he said, that astronauts had to carry passports.

“The first day or two up there,” Salman said, “you try to recognize the countries, especially Saudi Arabia. It stands out. It’s very distinct. Then you keep missing the countries and you look only at the continents. By the sixth day, the whole world becomes a beautiful blue and white and yellow painting. Those boundaries really disappear.”

Most Westerners never see an Arab like Prince Salman portrayed on television or in editorial cartoons. Most would be startled to read Will Durant’s The Story of Civilization and learn that during Europe’s Dark Ages, the Arabs “…led the world in power, order and extent of government, in refinement of manners, in standards of living, in humane legislation and religious toleration, in literature, scholarship, science, medicine and philosophy.” And most, if asked to describe an Arab, would probably use the same adjectives Americans did in a public opinion survey published in the Spring 1981 edition of the Middle East Journal–”barbaric and cruel,” “treacherous” “warlike” and “rich.” In short, the West sees the Arab as being a millionaire, a terrorist, a camel herder or a refugee, but not as a real human being.

Probably no ethnic or religious group–blacks, Jews and Hispanics included–has been so constantly and massively disparaged in the media as the Arabs over the past two decades. During Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the Los Angeles Times ran two front-page photographs one day: the first showed an Israeli soldier praying near Beirut, the second, a Palestinian guerrilla firing his rifle in combat. The message, however unintended on the editor’s part, reinforced the West’s general perception of both the Israeli and the Arab. One was a peace-loving man, the other a warmonger. Indeed, being Arab is a liability, for virtually everywhere outside of the Arab world he is stereotyped in negative terms.

When a school in suburban Washington, DC held a Halloween costume party not long ago, eight of the children showed up dressed as Arabs. Their accessories included toy guns, rubber knives, oil cans and moneybags. Among the synonyms for Arab in a recent edition of Webster’s Collegiate Thesaurus are vagabond, drifter, hobo and tramp. Even “Sesame Street,” the widely acclaimed children’s television show, once used an Arab figure to portray the concept of danger. And in 1978 when U.S. federal agents posing as wealthy Arabs from Oman and Lebanon offered bribes to congressmen in return for political favors they called their undercover operation Abscam (for Arab scam). Few people were offended but what would the public reaction have been had they named their operation Jewscam or blackscam? No matter. The Arab is fair game.

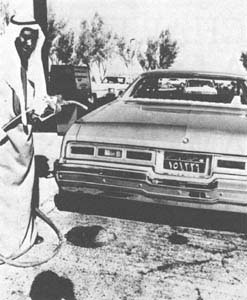

In early movies (“The Desert Bride,” “Son of the Sheik,” and Rudolph Valentino’s 1921 silent classic “The Sheik”) Arabs were characterized with what Jack Shaheen, author of The TV Arab, calls innocuous exoticism. They had harems and they did battle on the desert and they seemed humorous in their base, bumbling demeanor. Later, because of Israel’s popularity in the West and because Gamal Abdel Nasser’s shrill rhetoric about Arab nationalism was perceived as a threat to the West, they became the villains, warlike and untrustworthy. And with the oil embargo of 1973 they became the enemy. One auto bumper summed up the sentiment in the United States then: “Don’t Burn Oil. Burn a Sheik.”

To be sure, the Arabs themselves are partly responsible for the persistence of an unflattering image. The portrait of playboy princes frolicking in London, of terrorist thugs taking credit for repugnant deeds, of leaders who seem intent on establishing Arab identity by simply being noisy, none of this has done much to convince the average television viewer in North America or Europe that the Arabs are different from their stereotype. Recent terrorist attacks against innocents on the Mediterranean and in the Rome and Vienna airports serves, in fact, to reinforce prejudices against the Arabs as people. Yet do we think of the Irish as assassins because of the Irish Republican Army? Do we think of Americans as a nation of killers because of the 20,000 murders committed in the United States every year? If not then why should we hold 167 million Arabs in contempt because of the work of a lunatic fringe?

No Oil Wells Or Camels

The great majority of Arabs have never seen an oil well or ridden a camel. Statistically, they are poor not rich, farmers not entrepreneurs, political moderates not fanatics, pragmatists not idealists, capitalists not communists, law-abiding not crime-crazed. (I once told a Jordanian friend that the United States had half a million people in its jails and prisons and he shook his head in disbelief.) Arabs abhor violence and terrorism just as other civilized human beings do. They may take issue with Washington’s pro-Israel policies in the Middle East, but are genuinely fond of Americans as individuals and are fascinated with the American way of life. They consider Marxism an anathema, believing that anything atheistic must be inherently evil, and are not comfortable with the Soviet Union’s policies (such as the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, a Muslim country) or its diplomats (arrogant and heavy-handed, the Arabs say).

Like most third world people, the Arabs cannot fathom why no one understands them-and they do almost nothing to convince any one to bother. Their governments are inept at articulating their causes and unskilled at using public relations to manipulate opinion. They criticize (and are envious of) the Israelis for exerting great influence over American politicians and the American public, yet except for Egypt and to a lesser extent, Saudi Arabia, they have never made an effort at home or abroad to cultivate the foreign media, to lobby the politicians or to court the public. I asked one senior Arab diplomat who had been based in the United States for four years if he had ever spoken to a Rotary Club or church group, taken a journalist to lunch or visited a university campus, “No,” he said, “but I suppose that would have been a good idea.” He then went on to say that he didn’t understand why the Arabs were still stereotyped in the United States.

One of the losers of this lopsided battle for Western understanding are the 2.5 million Arab-Americans–the last U.S. minority to stand up for its rights. Their community is about half the size of the American Jewish population, yet its voice is all but silent. Unlike Jews, blacks and most other minorities, Arab-Americans have never united for political action. Their community is fragmented geographically, beset by the same cultural differences that divided their ancestors in the Arab homelands and leery of the resentment that might result from high visibility. Many of the older, conservative Arab-Americans see no need for Arab unity. So as a group Arab-Americans have maintained a low, apolitical profile and have integrated quietly into the American system, often dropping the Arabic names that Americans couldn’t spell or pronounce in favor of common ones like George or Frank.

Arab immigrants came to the United States in two waves. The first, between 1890 and 1920, was comprised mostly of unskilled Syrians and Lebanese Christians. They were seeking economic gain, not fleeing persecution or famine, and they tried to be more American than the Americans. Parents often forbade children to speak Arabic at home and eventually membership in the Maronite and Melkite Eastern Rite Catholics churches dwindled as the immigrants drifted to Western Roman Catholic parishes where they mixed with other ethnic groups. The new Arab-Americans worked as salesmen and tradesmen throughout the country and, although some Americans referred to them as Turks or even Chinese and South Carolina backed legislation in the early 1900s that would have prevented Arabs from becoming citizens, they generally found tolerance and opportunity in their adopted home.

The second wave, coming with the birth of Israel in 1948 and political upheavals in the Middle East in the 1950s and 1960s, changed the complexion of the Arab-American community. These new immigrants from Palestine, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Yemen were better educated than their predecessors and they brought with them a sense of Arab nationalism. Most were Muslims or Orthodox Christians. They kept their Arabic names and nurtured their appreciation for the Arabic language and the Islamic culture. Like every other minority in the United States, they had found pride in their roots, and that pride in turn has given them the confidence to take the first steps toward organizing committees for political action in the United States.

But escaping from the shadow of the Arab stereotyping is difficult. Newspaper editors still feel more comfortable dealing with the Middle East from the Israeli perspective. The public still treats Arabs as objects of curiosity and ridicule. Politicians, fearful of offending American Jews, still consider an association with Arab-Americans a potential onus. During the 1984 presidential campaign, Walter Mondale responded to Jewish pressure by returning $5,000 in contributions he had received from four Arab-Americans. A fifth contribution was returned to a woman simply because her name sounded Arabic.

“I would like my two daughters to be able to say with pride that their grandfather is from Lebanon, that they are American-Arabs,” said George Gorayeb, a New Jersey businessman who was once based in Bahrain for his company.

“I know, though, that that’s not going to happen, for a while anyway. I know that at show-and-tell at their school, or when kids wear ethnic costumes on special occasions, that there will be embarrassment, that they’ll have to apologize for their heritage, and frankly that makes me angry as hell.”

©1986 David Lamb

David Lamb, a reporter on leave from The Los Angeles Times, is chronicling the Arabs today.