The bad thing about booms is that they never last. They don’t lead to sustained economic growth and they seldom leave a healthy cultural imprint on society. The riches are spent, the boom ends, people move on. Spain frittered away its gold and silver from the New World four hundred years ago in a binge of high-living that weakened and disrupted the empire. Visit Brazil’s jungle town of Manaus and about the only reminder you’ll find of the Amazon rubber boom is the old opera house where Caruso once sang. Drive through the Nevada desert from Reno to Las Vegas and ghost towns stand in silent testimony to an era when silver was king. Will this one day be Saudi Arabia’s fate? Will twenty-first-century travelers to the kingdom find abandoned industrial complexes and empty cities being reclaimed by the desert?

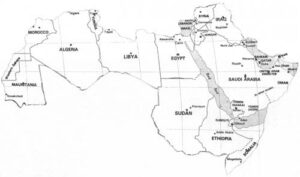

Saudi Arabia is as large as India and flying over it, on the flight from Cairo, one is struck by the emptiness below. It is a land with no rivers and no permanent bodies of water. It contains one of the world’s largest deserts, the Rub al-Khali (Empty Quarter), and only half a dozen population centers of note. Its population density is nine persons per square mile (compared to 10,132 per square mile in Washington, DC). But buried down there in that vast wasteland is one-quarter of the world’s known oil reserves, a reservoir of riches that will not be depleted for at least two hundred years.

As the birth place of Islam and guardian of its two holiest sites, Mecca and Medina, the kingdom is as religiously conservative as any place on earth. It has no theaters, allows no concerts and punishes those who consume alcohol with eighty lashes in public. Saudi Arabia, a homogeneous community of believers, is the only country named after a family, and the four thousand or so Saudi princes run it like a closely held family business, consulting with other power blocs such as the religious elders but holding ultimate authority themselves. Everyone takes life very seriously in the kingdom; it is not a place one goes to for laughs.

For the 75,000 Americans in Saudi Arabia–the largest U.S. business community in the Arab world–the kingdom’s harsh environment and puritanical lifestyle necessitate some mental adjustments.

“To be satisfied here,” said Mickey Lynch, project manager at a $2 billion refinery in Yanbu, “you have to say that you are going to make the most of it, going; to look for the good things–and there are a lot of them, like the Red Sea coral reefs that even Jacques Cousteau says are some of the most beautiful in the world.

“If you start dwelling on the negative aspects of life, you are going to be in trouble. Besides, whoever heard of a refinery being built in a rose garden?”

The modern history of Saudi Arabia began in 1748 when Mohammed ibn Saud, a besieged tribal chief, and Mohammed ibn Wahhab, a religious reformer, formed an alliance in Diriyah outside Riyadh. Together, with the sword and the Koran, they extended their rule throughout central Arabia, at times even challenging the ruling Ottoman Turks. In 1902, at the age of twenty-one, one of Saud’s descendants, Abdul Aziz ibn Saud–who 43 years later would sit in summitry with President Franklin D. Roosevelt–rallied his people and captured Riyadh from the competing Rashid family.

After defeating the Rashids, Ibn Saud set forth on a series of conquests that were to unite the warring tribes and squabbling sects of the Arabian Peninsula into a single nation, the world’s twelfth largest, which in 1932 he declared to be the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia with himself as king. Ibn Saud solidified his dynasty by marrying at least 120 women from tribes throughout the peninsula, but kept within Koranic restraints by never maintaining more than four wives at a time. As soon as a wife bore him a son, he divorced her and sent her back to her village. There she remained as the personal adornment of one man’s nationalistic campaign. “In my youth and manhood, I made a nation,” an aging Ibn Saud said. “Now in my declining years, I make men for its population.” When he died in 1953, his legacy included forty-seven sons and countless daughters. More important, he left his kingdom a legacy of stability, for today every Saudi recognizes Ibn Saud as the father of modern-day Saudi Arabia and thus accepts the legitimacy, politically and religiously, of the Sauds.

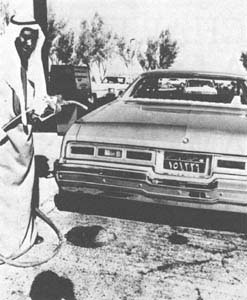

Saudi Arabia seems a strange place to be talking about tough times. Teen-agers roar through the city streets in the spanking-new Buicks and Pontiacs, ignoring signs that say, “Dear drivers: Your life is precious for your family and your country. Protect it.” Saudi families while away the weekends at the national pastime–shopping in glistening malls replete with $15,000 fur coats, diamond-studded watches and American-style soda fountains that serve hot-fudge sundaes. American businessmen sit with their Saudi counterparts in the piano bars of plush hotels, sipping orange fizzes and pineapple delights, discussing deals of Rockefellerian magnitude. The electronic pagers in their pockets beep like a chorus of crickets across the lounges, and Indian waiters hurry over, portable telephones in hand.

But times have indeed turned tough–at least by the standards of the boom years–and Saudi Arabia and the gulf states are coming to grips with a new reality: oil, like any mineral, is a resource of limited value, governed by the laws of supply and demand.

The worldwide demand for oil had been growing at a rate of 7.6 percent annually in the 1970s when prices spiraled skyward. As energy bills mounted, a global recession set in and the industrialized nations were forced to respond to what President Jimmy Carter called “the moral equivalent of war.” National policies encouraging conservation were adopted. Alternate sources of energy were utilized. Non-OPEC production was increased, particularly in Alaska, Mexico and Europe’s North Sea. Huge stockpiles of petroleum grew in Japan, Europe and the United States. And the public’s attitude toward the use of energy changed.

Thermostats were turned down, cars were driven less, speed limits were reduced, commercial jetliners lightened their flying weight–even removing plastic covers from magazines and scraping paint from fuselages–and began using computers to find the most fuel-efficient altitudes for flight. They saved millions of dollars and millions of gallons by keeping their engines shut down during delays at the gate, restructuring routes, adding more seats and reducing speed. On a five-hundred-mile flight, for instance, pilots found they could cut fuel consumption 7 percent by flying at 500 mph instead of at 520 mph.

At the Department of Defense, U.S. naval ships were modified to reduce drag in the water and an aggressive barnacle-cleaning program was ordered. On the highways truckers installed air-deflector screens above their cabs to reduce wind resistance. The result was up to an 11 percent savings in fuel. American-made cars that averaged 13.1 miles per gallon in 1974 were getting 17.3 miles by 1984, and in the span of that decade, according to the American Petroleum Institute, Americans cut their energy consumption by twenty-three percent. At the same time, the annual growth in the world’s demand for oil shrunk to just over one percent, a level that petroleum experts say may be sustained through the rest of the twentieth century.

All this led to an international oil glut and to diminished reliance on OPEC production. The United States’ reliance on oil imports tumbled to 4.3 million barrels a day–half what it had been in 1977–and much of those requirements have been met by newly expanded sources in Mexico and Britain; the United States’ reliance on Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf has fallen to only 2.5 percent of its total oil imports.

In March, 1983, OPEC responded to the downturn by making its first price cut in history, slashing $5 from the benchmark price of $34 per barrel. Saudi Arabia, the cartel’s giant, tried to regulate the flow of oil by closing and opening its taps to match global demands and conditions, just as the U.S. federal government regulates the supply of dollars on the market. But other OPEC members had economic commitments from the wild spending days of the ’70s boom and were often unwilling to abide by the limited production quotas OPEC set. Prices kept falling, and by 1986, for the first time in a decade, had skidded into the $9-a-barrel range, before edging back toward $17. OPEC’s fixed benchmark price became irrelevant; the price that mattered was the one established by supply and demand on the international spot market. Oil became a problem for marketers, not consumers, and OPEC became a cartel that could not control its own members, let alone the global pricing structure. Its share of world exports tumbled from 63 percent in 1979 to 38 percent in 1986, and the group in effect abandoned its attempts to curb production, thus ensuring an even greater glut. It was every man for himself.

The glut and the falling prices have been a boon to the consuming nations. They saved the industrialized West an estimated $100 billion a year, cooled inflation, pushed interest rates down and stimulated investment. There is, however, a flip side to the coin. Low, unstable prices also encourage consumption and discourage production. And this in turn could lead to a scenario that the Saudis and the gulf states are already drawing into their future blueprints: Sometime around the turn of the century, they say, the glut will end, prices will skyrocket again and the oil producers will regain control over the world economy. “Then you’re talking about a real boom,” said Bahrain’s minister of petroleum, Yusef Shirawi.

Although other developing countries would consider themselves blessed to have Saudi Arabia’s “problems,” the reeling economies on the peninsula and in the gulf are no frivolous matter. In three years’ time, the kingdom’s income has dropped from $103 billion to under $42 billion. Kuwait’s has been cut in half, to $9 billion. Budgets have been slashed, development projects put on hold, social expenditures reduced, personal spending habits adjusted.

“I used to give away ten or fifteen BMW’s a year to friends,” a Kuwaiti businessman said. “Now I’ve stopped that, and rather than buying my wife a new car this year, I’ve given her the ’85 Cadillac.”

The concentration of construction cranes that had become so common across every skyline they were referred to as the national bird of Arabia suddenly stood as listless as skeletons. Today they are a reminder of vulnerability instead of prosperity. Many shopping centers are almost morgue-like in their quietness and with their empty shops. One $200 million mall on Jeddah’s seafront boulevard suspended construction in 1986 when financing ran out and its owners began scurrying around for cash. “It’s up to God now,” said a spokesman for the firm.

It was, I thought, to the Arabs’ credit that they didn’t blame their economic vicissitudes on anyone. They have taken the price collapse quietly in stride, without threatening, cajoling or assigning guilt to anything but their own avarice and the fateful twists of the international economic order. It had been an exciting ride, and they greeted the twilight of their boom almost with a sense of relief, exhausted, needing some quiet moments to catch their breath and evaluate what had happened.

“Back in the early 1970s, when oil price quadrupled,” said Suleiman Selim, the Saudi minister of commerce, “we had two ways we could go. One was to advocate rapid development. The other was to go slow in order to keep our balance and disrupt the social structure.

“Now, you cannot yet really judge who was right and who was wrong. But you can say, given the oil glut and the decline in prices, that if we had not gone fast, we would have missed the train. And we did not lose our balance. Our political system is still solid, our country is still stable.”

The Saudis are proud of all that has been accomplished, but no toasts were raised to the pounding of the last golden spike. They know that they have gained their triumph and won their wealth without striving. No sweat has been shed in conquering their land. Their skin is smooth and their hands bear no calluses. The oil had been a gift–a gift from God, many said–and to put its proceeds to work the Saudis had summoned an army of two million foreigners and paid them well to plan, consult, maintain and toil in the blistering sun. This is, I think, Saudi Arabia’s greatest liability: No one has learned how to turn the nuts or tighten the screws, and there will soon come a day when every one can no longer be an executive.

“The Saudis’ biggest contribution was to have had the good sense to let progress happen,” a British businessman in Riyadh said. “They put their names up on the door and shared in the profits. But they’ve gotten good value for money. If Britain had gotten such a windfall, our government would still be in committee arguing how to spend it.”

In many ways, the impact of the oil boom has been surprisingly minimal. The wealth did not lead to any political reforms or give the Arabs much lasting leverage with the West. Nor did Saudi Arabia emerge as the powerbroker Washington had hoped for, though the Saudis had never wanted to lead in the first place. That was a role Washington and other capitals tried to thrust Saudi Arabia into, and it was contrary to the character of this country that had stayed out of the five Arab-Israeli wars and wants more than anything to simply be left alone, a position it secures by paying tribute to Syria, the Palestine Liberation Organization and friend and foe alike. Saudi Arabia is more comfortable building a consensus than pioneering a policy. It works, if goaded, behind the scenes, not on center stage, and it does not take risks. Caution is the trademark of every political decision, for Saudi Arabia remains a vincible country, a desert kingdom with a small population, a one-“crop” economy, an old fashioned political system and an Iranian enemy dressed in the robes of religious rectitude just across the gulf.

Presidents Carter and Reagan both pledged to defend the Arabian oil field-, against outside aggression. It is a promise that would be tough to fulfill. Pipelines running for hundreds of miles across the desert are vulnerable to terrorist attack and the wells themselves, spread over thousands of square miles, would be virtually indefensible in the face of a determined enemy. The security of the oil fields is the responsibility of the tribally based, 30,000-man national guard, commanded by King Fahd’s half-brother, Crown Prince Abdullah ben Abdel Aziz, whose support comes from the Bedouin but whose far-right conservatism often puts him at odds with other members of the royal family. Military analysts say Saudi Arabia would have only fourteen seconds’ warning time to scramble its jets if enemy planes were to cross the Fahd Line, an imaginary line drawn about ten miles inside of Iran, just north of the Persian Gulf coast. The Saudis could meet and hinder a major, sustained attack across that line, but could not turn it back without outside help.

Israeli jets regularly fly up and down the Gulf of Aqaba within sight of Saudi Arabia, and in 1981, apparently wanting to test the Arabs’ response, Israeli planes conducted a series of low-level mock bombing attacks on the Saudi’s northwestern air base at Tabuk. Yet few Saudis see Israel as the real threat. What they fear is that Iran will topple Iraq’s leadership and create a radical, fundamentalist bloc on their northeastern border. On their southern flank they worry about the only Marxist country in the Arab world–miserable, impoverished South Yemen. To the west and south, they are concerned about Egypt’s stability and communist influence in the Horn of Africa. At home they worry that every little sneeze may mask an expression of discontent among the youth, the soldiers or the religious elders. In each of these areas, the interests of Saudi Arabia and those of the industrialized West are in concert.

Saudi Arabia, in fact, has proved itself a better ally to the United States than some European governments. It has fought for price restraint within OPEC–it was Washington’s non-Arab ally, Iran, that first pushed for the wild price increases of the 1970s–shown disdain for the Soviet Union, refused free access to international terrorists, and linked itself to the moderate wing of the Arab bloc. It may rail against U.S. policies and bluster against Israel, but it knows its future, economically and militarily, is inexorably linked to the West and the Sauds are not likely to do much to threaten that relationship. If one wanted to imagine what real tumult in the Arab world would be like and what havoc an unfriendly government in Riyadh could raise with Western interests, one needs only to envision a Saudi Arabia in the hands of a Moammar Kadafi or an Ayatollah Rudollah Khomeni. About five minutes after the kingdom was seized by extremists, the royal families in the Saudi-dominated Persian Gulf sheikdoms would topple like houses of cards, and the eastern flank of the Arab world would become a Mecca of opposition to the West, to Israel, to moderation within the Islamic community, to sensible oil-pricing policies.

“Look at how much little Kadafi has been able to screw things up in Africa with his few billions (of dollars),” William Quandt, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, told the Los Angeles Times. “The Saudis have far greater resources than Libya. So far, when Saudi Arabia has chosen to spend its money for political purposes, it has usually been on behalf of courses we can support. If that money went into troublemakers, it could be difficult.”

Unfortunately, though, Congress often has trouble differentiating between its friends and enemies in the Arab world and has spent little time examining Saudi Arabia’s contributions to Western interests. To many Congressmen, anyone who doesn’t want to join the Washington-Jerusalem axis is a recalcitrant, and potentially an enemy. However politically appealing that platform may be at election time, it is a reckless policy which threatens to throw away the friendship that the Arabs want to maintain. If Saudi Arabia cannot defend itself and the tide of Khomeinism spills through Arabia and flows on to Jordan, Israel’s security–indeed its existence unless the United States is willing to go to war–could be threatened as never before.

With or without genuine American support, though, Saudi Arabia is in a good position to cope with the pressures of the post-boom era. Economically it can withstand a protracted oil-price war better than any producer; it costs the Saudis only $3 per barrel to extract their black gold–compared to upwards of $9 a barrel in the North Sea–and with known reserves exceeding 170 billion barrels, Saudi Arabia remains wildly wealthy by any standard. Politically the House of Saud does not seem a probable victim for the type of internally motivated, vengeful extremism that swept aside the Pahlavis in Iran, as long as it can continue to address the wants of the military, the ulema (religious establishment) and the middle class.

But Saudi Arabia could change–at least in terms of policies even if the system itself remained intact–when Crown Prince Abdullah one day succeeds King Fahd. Abdullah is the black sheep of the royal family. He does not want to be identified with the West, particularly the United States, and he seeks better relations with the hard-line Arab states, such as Syria. He is an ambitious man, more pious and more of an Arab nationalist than Fahd, and a Saudi Arabia with Abdullah as king would be far less responsive to Washington’s interests than has been the present monarchy.

Barring the exportation of Iran’s revolution, the stability of Saudi Arabia and the gulf states may be determined in the long run by the very thing the royal families created through their dispersal of oil money–the middle class. Throughout the Disposable Decade everyone lived beyond his means, and tomorrow was always better than today. There will be displeasure as the gold-plated fairy tale fades, displeasure that will require adjustments and re-education. The House of Saud and the gulf dynasties will have to fine tune their arcane and burdensome decision-making processes that straddle the line between tradition and modernization and that have given money but not power to the burgeoning middle class. The middle class, having known education, prosperity and the passion of unfettered expectations, will set the tone and pace in the Retrenchment Decade as the oil producers try to consolidate their gains from the boom of the ’70s. Its children, having traveled the world and smelled the fruits of democracy abroad, may not gracefully accept forever a tightly controlled society whose freedoms are limited and whose opportunities for significant political change are few. They will make the demands to which the rulers must respond if the House of Saud is to survive into the 1990s and beyond.

©1986 David Lamb

David Lamb, a reporter from The Los Angeles Times, concludes his reporting on the Arabs today.