In a once-forgotten corner of the world, a young sultan has led his people out of the Dark Ages and onto the threshold of the 21st Century. The journey has taken but a second on the clock of history, yet in that flash Oman has moved boldly to challenge the notion that oil-induced modernity is incompatible with traditional Arab values.

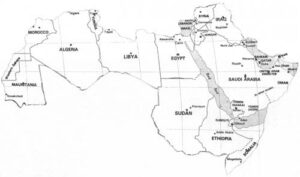

Oman, about the size of Kansas, is situated on the southeastern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. It overlooks the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow passageway for about one-fifth of the world’s daily oil production, then stretches inland through mountain gorges, rocky plains and searing-hot plateaus. The region is so rugged that less than 0.2 percent of the land is farmed and so rooted in conflict that Oman’s borders with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are still undefined and its border with South Yemen is in dispute. For centuries, anarchy, insurrections, invasions, civil wars and tribal fighting racked this starkly beautiful country whose name translates as the “peaceful land.”

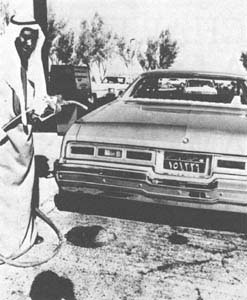

I arrived in Muscat, the capital, at night. The outline of 15th Century Portuguese forts cast long, soft shadows over the desert and the moon was almost bright enough to read by. On the four-lane road from the airport to the hotel, Buick limousines and Datsun 280-Zs roared by my Mercedes Benz taxi at break-neck speed, weaving past motor scooters whose drivers had rifles–old British Enfields or the prized Russian Kalashnikov–slung over their backs as a symbolic mark of manhood. Reaching up the hillside were clusters of modern, spacious homes, air conditioners humming, lights ablaze, and in the gully below them, as though they were a permanent part of the landscape, a dozen tents with TV antennae protruding. Outside each was parked a Toyota pickup truck. Donkeys and camels grew fat and lazy grazing nearby.

Unlike the other oil-producing sheikdoms and kingdoms on the peninsula and around the Persian Gulf, Oman has a long history of contact with the outside world, a history that goes beyond the confines of the desert. Its people were great seafarers whose trade routes carried them to Pakistan and China more than a thousand years ago and whose 17th Century empire included most of the southern Arabian Peninsula and Zanzibar and Mombasa on the east African coast. Except for a brief period of Persian rule, the Omanis have remained independent since expelling the Portuguese in 1650, and their history seems to have made the Omanis more worldly in outlook and less fearful of change than many of their neighbors.

Oman did not start producing oil until 1964, and its reserves are modest compared to those of three nearby super-rich friends, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. But to appreciate how Sultan Kaboos ibn Said has used his resources to transform the sultanate, it is worth opening the time capsule that, less than two decades ago, had made Oman as paranoid and isolated as Albania is today. Oman’s age of darkness began in 1938 when Kaboos’ grandfather abdicated in favor of Kaboos’ father, Sultan Said ibn Taimur. Suddenly the past was gone and for the next thirty-two years, until 1970, the future was to become something best ignored. The new sultan closed Oman’s doors to the world. The country was now secure; it was going back into the past.

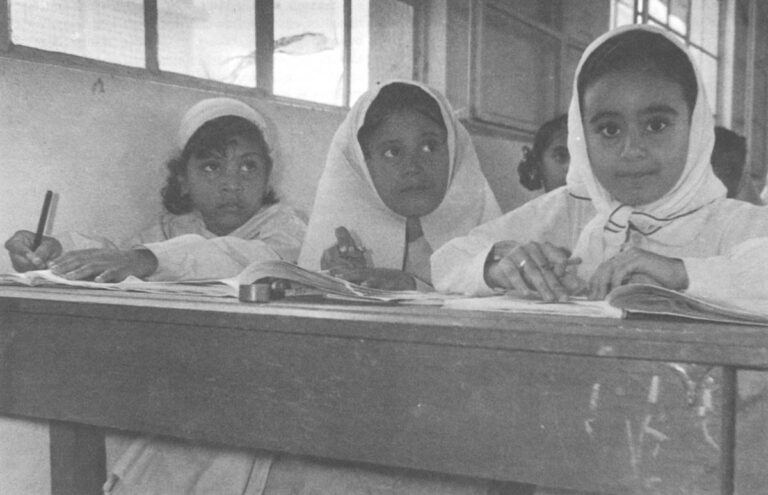

Fearful of any outside influences that would corrupt Islamic and Arab traditions, Sultan Said made it illegal to wear glasses, ride a bicycle or own a radio. Western clothes, dancing and smoking were banned and the ban was enforced with public floggings. Women were not permitted to attend school or appear in public unless cloaked head to toe in black abeyas, a shapeless, sexless garment that gives the wearer a distinct resemblance to a penguin. Oman’s missions abroad were closed, virtually no foreigners were allowed into the country and the few students who had gone abroad to study were denied the reentry visas needed to come home.

As recently as 1970, the year after Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, the wooden gates to Muscat swung shut each evening at dusk. Those walking the streets after dark had to carry a lantern at arm’s length and continually announce themselves to avoid the risk of being shot as strangers. In the entire country, there were only three miles of paved roads, twelve doctors, fifteen telephones and three religious schools, which Sultan Said grudgingly allowed to function despite his opposition to education. The sultan lived in a mud palace in Salalah and kept the national treasury under his bed, communicating with the capital, 500 miles north, via shortwave radio. His people eked out a meager living through subsistence farming and fishing. Their per capita income was $100.

To this day no one can fully explain what motivated Sultan Said. Probably it was nothing more than fear of change, of the unknown, of new ideas, the same fear that grips so much of the Arab population today as it tries to cope with the temptations of imported Western technology and culture that came with the oil boom of the 1970s. But new ideas were spreading, particularly among the young, and they were coming from an unlikely place, Saudi Arabia. By then, in the late 1960s, Said had made two mistakes that ensured Oman could not forever remain immune to the forces of change: He had granted an oil concession to the Iraq Petroleum Company, owned jointly by several of the largest international oil firms, and he had sent his only son, Kaboos, off to Britain to be educated at Sandhurst, the military academy.

Kaboos, a teetotaler and something of a moralist, returned home after graduating from Sandhurst and spending a year with a British regiment in West Germany. He had discovered the world. His new passion was light opera and he would lay on his bedroom floor for hours, listening to Gilbert and Sullivan. His affinity for Western culture so infuriated the sultan that he smashed Kaboos’ favorite album, “The Pirates of Penzance,” over his knee.

Kaboos protested and was placed under house arrest for three years.

But desert justice was to prevail. On July 23, 1970, Kaboos and a handful of his father’s trusted British advisers appeared at the palace with an ultimatum that the sultan abdicate. Sultan Said fired a few harmless shots into the ceiling, then meekly boarded a waiting Royal Air Force plane bound for London. He was installed in a suite at Claridge’s Hotel, where he died two years later at the age of fifty-eight.

I met Sultan Kaboos several days after I flew into Muscat. He was a strikingly handsome, gracious man, fortyish and soft-spoken. His clipped beard was turning from gray to white, his eyes were sharp and dark like those of a falcon. In the belt of his ankle-length dishdasha was stuck an ornate, silver khunjar (dagger). He had divorced his wife because she bore him no son and had remained a bachelor, leading to much speculation about who was in line for the throne. I had been warned before hand that Kaboos would not talk about the coup–”When you overthrow your father you have some painful memories,” the sultan’s British adviser had said–so we talked about Oman’s rapid development since 1970, and I asked if perhaps he, like Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi of Iran before him, wasn’t moving his 980,000 subjects faster than they were prepared to go.

“If you had asked me that nine or ten years ago,” he said choosing his words carefully, “I’d have replied, ‘Well, hopefully we will do all right,’ but within myself I’d be asking, Are we really ready for this? Now I can honestly say, yes, I think we can progress without destroying ourselves, our culture, our way of life. We are enjoying modern ways but we are not losing ourselves in them.”

Per capita income had soared to $1,000 in the years since his father’s exile, 1,300 miles of superhighways stretched throughout the country, the fifteen telephones had grown to 30,000, a $400 million university, Oman’s first, was under construction. “It’s hard to believe that so recently this was a poor country with no progress at all–we were just at a standstill,” said the university’s elderly director, Amor ibn Ali. There was now one hospital bed for every 500 people in Oman, a ratio that compared favorably with that of Western countries, and the 490 schools had an enrollment of 168,000–boys as well as girls. Kaboos was particularly upbeat the day I talked to him: he had just announced plans to create the first national symphony orchestra in the Arab world and the initial group of young Omani musicians was about to embark to Vienna for seven years’ training.

“His Majesty marches to his own drummer,” one of his ministers said, and I couldn’t take issue. Kaboos had struck a close alliance with the United States, giving Washington access to Oman’s military facilities in the event of a threat to Arabian oil fields. He had 525 Britons in his efficient 20,000-man army, some of them in command positions–an oddity in an age when Arab governments pretended they depend on no non-Arab friends–and while most other Arab leaders were condemning the Egyptian-Israeli treaty of 1979 he was calling the accord a significant, though less than perfect, first step toward peace. He was deeply suspicious of the Soviet Union’s global intentions and privately critical of other heads of state who wasted too many idle words espousing the cause of Arab unity.

Although Kaboos ran an authoritarian monarchy–there was no constitution, no suffrage, no political parties–he appeared to have maintained the loyalty of his people. But the monarchy was something less than absolute. Like a desert chieftain, the sultan reached consensus through consultations with tribal leaders and cabinet ministers and he made sure he didn’t lose touch with -the national pulse by taking three-week safaris each year, moving across the desert in a caravan of Land Rovers. He spent the day talking to villagers and slept each night in a traditional black-hair tent.

Kaboos has kept Oman aloof from the Middle East’s turmoil, yet trouble is never far from his shores: He worries about Iran’s announced intention to export its radical Islamic revolution and about nettlesome South Yemen, the only Marxist country in the Arab world, and he casts a leery eye at the Horn of Africa, where Moscow has implanted itself in Ethiopia. As a result entry into Oman is carefully controlled. Western businessmen, for instance, can easily obtain visas, but Libyans and Iranians are persona non grata, and Palestinians and citizens of Eastern Bloc countries are granted visas only after intelligence checks that can take weeks. When I asked one government official why Oman had a policy that seemed to discriminate against Arabs, he replied, “Because Englishmen don’t plant bombs.” That, I thought, summed up an important characteristic of the Middle East: Arabs may embrace their brethren, but they don’t necessarily trust them.

Oman’s future stability may well rest on the shoulders of one man, Sultan Kaboos ibn Said. And that is probably a good omen for the Omanis–and for Western interests. Kaboos has put an Islamic and Arabic overlay on the Western-inspired modernization of his country. The people believe they are moving at their pace, not his. They view the sultan as Oman’s religious leader as well as its head of state, thus bestowing a legitimacy on Kaboos that the Shah of Iran did not enjoy. Having experienced the unpleasantries of being forced to step back into the past, they thirst for a taste of tomorrow as long as they do not have to sacrifice their Islamic or Arab identity in the process. Today, for example, if a father does not enroll his daughter in school, he is visited by an official from the ministry of education and encouraged to reconsider. If he refuses, believing that a Muslim woman has no need of an education or a profession, the matter is closed and his daughter is allowed to dwell forever in the realm of the ignorant.

The lesson of Oman, I think, is that change does not have to be threatening in the Arab world if people are made to feel that they have a choice, that they have control and are the masters, not the victims, of their destiny. New ideas eventually become a greater force than religion. Whether it is in the United States or the Arab world, the strength of the Moral Majority ebbs and flows, the attraction of religion swings like a pendulum. One may cling tenaciously to the past, but change becomes inevitable and the smell of it in the wind is irresistible, especially to the young. The challenge is to graft what is good from other cultures to one’s own society, not to reject all that is foreign out of hand. It is, as Sultan Kaboos has shown, not an impossible task.

©1986 David Lamb

David Lamb, a reporter on leave from The Los Angeles Times, concludes his reporting on the Arabs today.