In late 1982 in a Salt Lake City courtroom, the United States mounted a complex and costly legal battle against a small group of its own citizens who struggled to prove that their government had knowingly subjected them and thousands of others to dangerously high levels of radiation during the nuclear weapons testing program in the 1950s and early 1960s. That exposure, these downwind residents claimed, killed their loved ones and produced an epidemic of cancer among themselves.

The government denied it had harmed these people. It denied it had any responsibility to compensate them for their losses. Yet that assertion was totally contrary to a finding 2 1/2 years earlier by a high-level federal panel created especially to examine these claims. That panel unanimously concluded, in a report that was quickly labeled secret, that the government had injured some downwind residents and was morally and legally bound to compensate them.

What happened in the interim? Why were the people of Utah, Nevada and Arizona–patriotic and conservative Americans who believe they were used as human guinea pigs in this nation’s experiments with the atom bomb–forced to go to court in an attempt to establish their claims? Why were the recommendations of the federal panel suppressed and ignored?

The answer is at once tragic and alarming.

These nuclear guinea pigs were selected by their government to be participants in yet another testing program. They would become the subjects of a legal experiment that, many believe, could set a precedent for countless other Americans now and in the future who have been sickened or killed by dangerous substances. Again, they have become caught up in a government strategy that viewed them only as pawns.

It all began in the summer of 1979. Pressure was mounting on the Carter administration to deal with the thorny question of the government’s responsibility to hundreds of downwind residents who claimed injuries as a result of fallout from the testing program.

Several well-publicized Congressional hearings into the matter had been held, and from Capitol Hill came a request that the administration make its policy clear. The governor of Utah, who had released 11 pounds of secret federal documents pertaining to the tests and the resulting fallout on the residents downwind of the Nevada Test Site, had visited the White House seeking the president’s aid.

A year before, a federal task force had determined that there were no safe levels of radiation and that exposure to radiation at low levels could in fact also cause cancer. But the report ignored the question of government liability for injuries caused by exposures from the testing. And a growing number of people were demanding an answer to that issue.

Out in Utah, Arizona and Nevada, lawyers were busy filing claims against the government on behalf of downwind residents. The amount sought in the claims already exceeded $2 billion and the attorneys were still processing others. They made it clear they were ready to go to court and prove that the only postwar victims of America’s nuclear weapons program were its own citizens.

William Gray Schaffer, a 37-year-old, red-headed deputy attorney general, was summoned to the White House, where members of the president’s domestic policy staff and other advisors debated an appropriate response.

A short time later, on July 20, President Carter announced the formation of a new task force and gave it a dual assignment. First, the group was to study and recommend alternatives for compensating people with radiation-related illnesses as a result of the weapons tests. Then it was to examine other radiation compensation issues, including those involving occupational exposures. The task force consisted of representatives of the Departments of Defense, Energy, Labor, Health, Education and Welfare, the Veterans Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency. Schaffer, as the representative of the Department of Justice, was named chairman.

Schaffer, now a lawyer practicing in Washington, looks back on that assignment with a degree of cynicism. Although he believes the Carter administration approached the issue with an open mind, his experience in government has taught him one thing: “If you want to duck an issue in government,” he said recently, “the way to do it is to create a task force. Give them a deadline and you’re not going to get a report. Then, it would be very easy to blame it on the task force.” Besides, he added, “getting a half-dozen government agencies to agree on anything is also an impossibility.”

In late January, 1980, Schaffer telephoned the White House. The task force’s report on phase one was completed. Its recommendations were unanimous. The response on the other end of the line was, as Schaffer recalls, silence.

When the White House finally did respond, it ordered that the 57-page report be kept confidential. Within two days, however, it had been leaked. Although the report received a limited circulation in Washington, it never was officially published. Copies exist in archives maintained by the Departments of Energy and Justice.

At the heart of the report was a recommendation that the government not litigate the claims filed by the downwind residents. The “serious drawbacks” to a court battle included “substantial” cost and “a risk of establishing judicial precedents which could be harmful to the government in other radiation and toxic substance litigation.”

The task force noted that a court fight “necessarily focuses attention on whether or not the federal agencies and officials involved in the test program behaved properly. Such emphasis on allegations of negligence and wrongdoing of federal officials tends to obscure what the task force believes to be the most important issue–the actual health impact of the test program (even if conducted flawlessly) and the government’s present responsibility to the population affected.”

Another drawback, from the claimant’s perspective, is that litigation requires the individual seeking damages to prove that his injury was directly caused by exposure to the radiation. Such a burden of proof, the task force noted, represents an insurmountable obstacle in radiation-injury cases, because the cause of cancer and the precise health effects of low levels of radiation remain unknown and a matter of much scientific debate.

The task force instead urged the government to compensate victims of fallout-related illnesses through a special administrative system created specifically for this incident. Such a system would, in the words of the task force, fairly and equitably resolve a problem that “is not only legal, but also raises issues of public and social policy.” It would offer a “middle ground” between litigation of the individual claims and a blanket compensation program then being considered in the Congress.

“The government’s test program caused fallout, and fallout emitted radiation which increased the risk of illness in the entire population exposed,” the task force unanimously concluded. “This exposure in all probability caused a small number of cases of death or disease for which the government should accept responsibility.”

The White House promptly disbanded the task force. Its recommendations were ignored. And the government began to mount a major defense of its nuclear weapons testing program.

On Sept. 14, 1982, the case of Irene H. Allen et.al. vs. United States went to trial in a Salt Lake City courtroom. The list of those people seeking damages from the federal government for injuries they believe are fallout-related fills 18 1/2 typewritten, single-spaced pages.

By the time the testimony concluded on Dec. 18, 1982, the transcript exceeded 6,600 pages. More than 2,000 exhibits had been introduced. The federal government had launched a $6.6 million scientific study to reconstruct fallout levels in an effort to bolster its claims that radiation received by downwind residents was too low to cause any adverse health effects.

Decision Pending

The decision in the massive litigation–which actually involved just 24 of the 1,200 named plaintiffs–is pending. Both sides in the case have vowed to appeal the ruling by U.S. District Judge Bruce W. Jenkins if they lose. In the words of one of the 24 litigants, “this will remain in the courts until everybody is dead, buried and forgotten.”

Why did the government proceed with a lawsuit in direct disregard for the unanimous recommendations of its blue-ribbon advisory panel?

Why was the list of “serious drawbacks to litigation” set forth by the task force ignored?

Why did the government initiate a massive legal battle–that already has cost millions of dollars and is far from a conclusion–against a handful of its citizens who can make a compelling case that they were, in fact, considered expendable by federal authorities?

Ironically, the person with some of the answers is William Gray Schaffer who, upon completion of his task force duties, was selected by the Attorney General to head up the government’s defense in the fallout trial. Although he remained convinced the administrative compensation system offered the correct solution to the problem, a conviction he holds today, he accepted the litigation assignment, aware that the compensation recommendations were not without problems for the federal government.

He supervised preparation of the case for a year, quitting Justice in 1981 in a disagreement over funding for the defense. His superiors, he claims, were not willing to spend as much money as he believed was necessary to present a proper case. “I just felt (this represented) a tremendous potential as an educational vehicle about radiation and the whole process of government decision making,” he recalls.

The task force, he admits, initially may have been naive. “A lot of us thought, myself included, that good sensitive people in government could put their heads together and rectify this situation.” But, he adds, the task force “underestimated the complexity of the problem.” Of major concern in the White House, according to Schaffer, was the potential cost of such a compensation program and the precedent it might set in future liability claims against the federal government. (Those same two problems were among the drawbacks of litigation cited by the task force.)

At the same time, he added, there came the realization that “this was not a problem you could draw a circle around and isolate.” The fallout had spread to areas all over the United States. Because no one could say with certainty how much radiation could cause cancer or who is susceptible, a claim could be filed by just about anyone. The problem had no simple solution and an enormous potential for unlimited legal and policy ramifications for the future.

There exists another fundamental reason for the government’s decision to do battle with its citizens which can never be discounted. And that was the concern in powerful places that the claims represented a threat to the future of the nation’s nuclear weapons development and energy policies. Historically and to the present day, those who believe America’s future is inextricably linked to the atom close ranks and fend off the menace when they perceive a challenge to that belief.

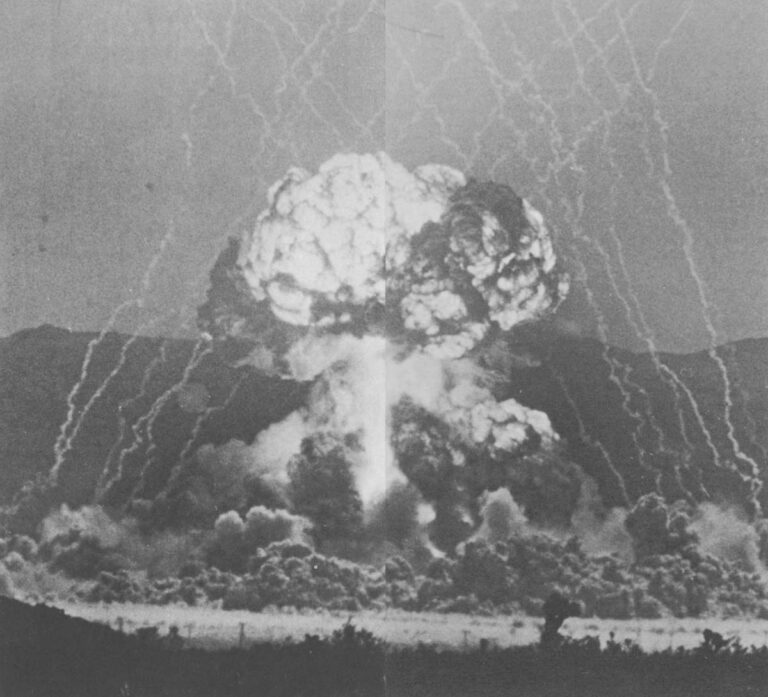

This response has persisted since the first atomic bomb was tested on July 16, 1945. A handful of men have tightly controlled the decisions involving atomic weapons. They have controlled the data relating to it (almost all research into radiation-related health effects has been conducted in national laboratories operated by defense or energy departments). And they have almost without fail controlled debate by the government over the conduct of nuclear programs.

The consequences of this nuclear oligarchy may well be, as Utah Gov. Scott M. Matheson told a Congressional committee in 1979, “that in the name of national security we have lost our perspective about the public health, and the credibility of the U.S. government (has) lost some real ground.”

Downwind Victims

For the people who lived downwind of the Nevada Test Site, the government they revered and trusted has delivered them a one-two punch. It subjected them and their families to high levels of fallout during the 1950s, assuring them all the while that they were perfectly safe. Then, when those assurances proved false, when every neighborhood and every town in the path of the fallout seems caught in an epidemic of cancers, that same government denied responsibility.

“One has to wonder about the justice of a position that says, ‘We convinced the people they were safe; now bar their death claims because they believed it,’ ” observed Dale Haralson, an attorney for the downwind residents, during pretrial arguments in the lawsuit.

People like LeOra Hafen of St. George, Utah (whose husband Karl and daughter Karlene died of cancer) and Blaine Hart Johnson of Cedar City, Utah (whose daughter Sybil died of leukemia), and Helen Nisson of Washington, Utah (whose son Sheldon died of leukemia), and Dwight Pectol of St. George (whose wife Lisa died of a brain tumor when she was five months pregnant), and Jane Whipple Bradshaw of Hiko, Nev. (whose husband Kent Whipple died of lung cancer) believe themselves entitled to compensation for their deceased family members.

To succeed, the victims must prove that government officials were aware of the dangers of fallout and continued nonetheless to subject the populace to it. Or, they must demonstrate that the government acted negligently in its conduct of the weapons testing program. Those burdens of proof are difficult but not insurmountable. To win their case, however, the downwind residents must do one other thing which many consider impossible: They must prove to a court’s satisfaction that the illnesses were the result of exposure to radiation.

U.S. Department Of Energy

To do that, they must rely on scientific data that is far from conclusive. What data exists on fallout from the early weapons tests is spotty and of extremely questionable accuracy. Validity of the numbers represents only a fraction of the problem, however. Scientists just cannot identify with any certainty the health effects of radiation. They speculate that fallout has increased the risk of cancer among those exposed to it. But a radiation-induced cancer cannot be distinguished from other cancers. And speculation about causes carries little weight under the law.

Thus, the downwind residents find themselves caught in a dilemma that confronts a growing number of Americans seeking compensation for injuries they believe were caused by hazardous substances: Science cannot provide them with the proof required by the courts. The traditional system of tort law which governs injury claims is wholly inadequate in its present form to deal fairly with such complex questions.

Task Force Report

For precisely these reasons, the task force created by President Carter in 1979 recommended the government create an administrative compensation system to deal with the radiation claims. According to the task force’s report, the advantage of such a system included:

The ability to provide benefits to those “having the highest probability of radiation-induced” illnesses. The burden of conclusively proving a cause of the illness would be eased for the claimant, who would only have to demonstrate an exposure to the fallout and scientific evidence of a statistical probability that his or her injury could have been caused by it.

Reduced risk of “creating an adverse judicial precedent” that could be applied to an enormous number of environmental pollution lawsuits and open up the government to many thousands of claims.

It rendered moot the issues of government wrongdoing or negligence, and thus sidestepped any controversy about continuing with the nuclear weapons testing program.

And finally, the report noted, “it will not cast the government into an adversarial role vis-à-vis the downwind residents.”

In the end, it is this final aspect of the lawsuit that is most troubling to the people of Utah, Nevada and Arizona. Many of them are Mormons and extremely patriotic. “The people here think the government is next to their church” in credibility and integrity, according to J. MacArthur Wright, a St. George, Utah, lawyer representing the claimants.

Elizabeth Wright, whose father Arthur Bruhn died of leukemia, expressed a sentiment shared by many in that area. “We did what we were asked to do by the government and the community went all out. In return, (we) were used, (we) were conned. They knew (of the hazards). They knew and they did not tell us.”

Two Men Who Loved The Land

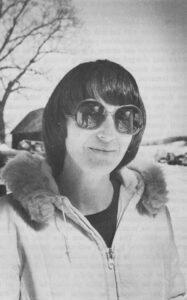

Lewis Bowler and Arthur Bruhn were as unlike as any two men could be, except in one respect: They loved the land in which they lived. They spent as much time as possible in the mountains and desserts of their native state of Utah, awed by the desolate beauty and humbled by the forces of nature that created it.

In the end, their widows believe, it was the love of that land and the out-of-doors that killed them.

Both men died of virulent forms of cancer. Both men had stood amid the splendors of the Utah countryside and watched the dazzling might of America’s nascent nuclear weapons testing program swirl around them, believing the assurances of their government that they were, indeed, a part of “history in the making.”

The final chapter of that history has yet to be written.

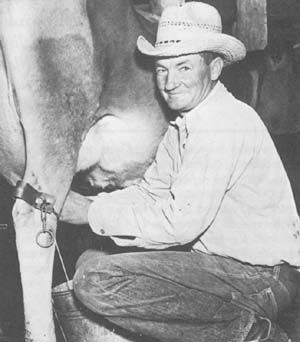

When asked to describe her husband, Mildred Bowler is quick to reply: “He was just a natural cowboy, I would say.” He lived on a ranch in the tiny crossroads of Veyo, in southwestern Utah, for 50 years. After completing his chores in the early morning, the would load his horse into a trailer and drive 50 miles southwest into Nevada to care for his herd of cattle on their winter range along Beaver Dam Wash, sometimes remaining at the cow camp for days at a time.

“Some people work at it because they have to,” recalls Mildred Bowler. “He did it because he loved it. I have said a lot of times he couldn’t have stood the hours and the work if he hadn’t loved it. But it was part of his life. He knew the cattle just like he knew people.”

“We didn’t travel much. Once, we wanted to go to Bryce (National Park). He said, ‘Oh, I see prettier country out where the cows are than I would over there.’ “

At the request of his government, Lewis Bowler began wearing a film badge to measure his exposure to fallout from the weapons testing going on at the nearby Nevada Test Site. The Atomic Energy Commission tested the milk of their dairy herd for radioactive iodine. But it was not until November, 1982–three decades after her husband’s exposures began and 15 years after his death–that Mildred Bowler learned of the results of any of that monitoring. A federal scientist in a Salt Lake City courtroom testified that, based on government estimates calculated almost 30 years later, Bowler had received a cumulative skin dose of 31,000 millirems and a whole-body dose of 4,500 millirems. In the 1950s the acceptable dose of whole-body radiation for the average person was 1,500 millirems. Today it is 500.

Willard Lewis Bowler, cowboy, died at age 56 in December, 1967 of metastatic melanoma–a deadly skin cancer. His cancer had begun as a blackened fingernail that would not heal. Doctors removed his finger, but the cancer had spread throughout his lymph system. As she busied herself canning peaches in her kitchen one evening earlier this year, Mildred Bowler reflected on her husband’s death and its possible cause.

“It’s hard to prove anything. We don’t have definite proof. But you grasp at everything.” As if more explanation were needed, she paused and added: “We just couldn’t find any other reason for his cancer.”

Reluctantly, she joined in the lawsuit against the federal government seeking compensation for her husband’s death.

She, like many of the 1,200 people involved in the lawsuit, make it clear that winning a payment from the government was only a secondary consideration in their decision to sue. “About the money: We didn’t feel that was as important. We felt we should bring the thing out into the open so it won’t happen again.”

Unlike many of her fellow claimants, who remain stolidly pro-nuclear and supportive of continued weapons testing at the Nevada Test Site, Mildred Bowler wonders if the underground detonations will prove as hazardous as the above-ground tests that produced the fallout in question. “Why do they (government officials responsible for weapons testing) continue to subject the people to these things? I don’t know, I’m not a scientist. Are these tests going to help us or destroy us?”

Arthur Bruhn was living proof of his favorite adage: Once you get the red sand of southwestern Utah in your shoes, you never get rid of it. A geologist by training, he was, by all accounts, a born teacher who thrived on sharing his love for Utah’s natural surroundings with anyone who would listen. He turned down teaching offers elsewhere to remain in St. George, a closely knit town that was home of Dixie College, where he taught and where he later served as president.

Bruhn would take his geology classes on field trips, including a number to witness the brilliant explosions, plainly visible 150 miles away at the Nevada Test Site. He was at Beaver Dam Wash on March 17, 1953, observing the detonation of a test code-named “Annie.” The Los Angeles Examiner carried an eye-witness account of that blast from Bruhn, who told the newspaper it was “a most beautiful flash, but (we) felt no shock wave.”

He was given a radiation badge to wear at school. He was never informed of the data collected from that badge.

Bruhn died July 5, 1964 at age 47 of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. His widow, Lorna, joined the lawsuit against the government to fulfill a deathbed request of her husband to “do everything you can to keep this tragedy from happening to another family.” Sitting in her book-filled living room recently, Mrs. Bruhn, a retired school teacher, added: “I don’t want this to happen to anybody else. The heartbreak is too much.”

The Bruhns’ daughter Elizabeth, sitting with her mother, has also joined in the lawsuit. Unlike her quiet-spoken mother, she is vocal in her anger with the federal government and believes it owes an enormous debt to the people of the region who lived amid the fallout from the nation’s atomic weapons testing program.

“This is a population here which has borne the burden of the defense of this country, so everybody in this country should contribute something in return–even if it is only a dollar.”

©1984 Susan Q. Stranahan

Susan Q. Stranahan, editorial writer on leave from the Philadelphia Inquirer, is reporting on victims of environmental poisoning and how they have been compensated.