In June, 1951, Patsy Takemoto Mink received her law degree and the news that she and her husband John were expecting their first child. She went to the University of Chicago’s prestigious Lying-in Hospital for her prenatal care. There, her attending physician prescribed special vitamins to ensure, as she recalls, “a healthy baby.”

Unwittingly, she became a human guinea pig, as did the female child she was carrying. Not for 2 1/2 decades would she even know of her participation in a major medical experiment to test the effectiveness of the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol, or DES. And when she finally did learn, in March 1976, the news came in the form of an ominous advisory from the university: As a result of the 1951 medical care, her daughter, then 24, faced an increased risk of contracting a rare form of cancer and a variety of other health problems, the extent of which remain unknown to the medical profession today.

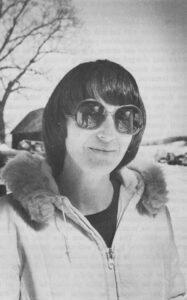

Mrs. Mink, who would later be elected to the United States House of Representatives from her native Hawaii and serve as assistant Secretary of State in the Carter Administration, was among 2,000 mothers-to-be who, without ever being consulted or informed, were part of a 20-month university experiment to test DES on pregnant women. By virtue of the fact that she randomly was assigned an even number on the day she made her initial visit to the hospital’s obstetrical clinic, she and her baby became part of the group selected for exposure to large doses of DES.

That group proved DES of no value in preventing miscarriages and other pregnancy problems. Researchers reported their conclusions in 1953. Unbeknownst to them–or anyone else at the time–the experiment was far from concluded. It continues to this day; the unexpected side effects of DES still haunt the participants in the Chicago experiment and millions of others who were exposed to the drug.

In 1977, Mrs. Mink and two other women who also had been uninformed participants in the Chicago study instituted an experiment of their own: this one legal, not medical. On behalf of the women given DES, they sued the university and Eli Lilly & Co., manufacturer of the DES, for making them guinea pigs. “This was a medical crime,” said Mrs. Mink recently. “My feeling then was that no one ought to get away with it.” Her feelings are unchanged today.

Their claims against Eli Lilly were dismissed by a federal judge who ruled that because the women had suffered no actual physical harm they had no grounds to sue the drug company. He rejected their argument that the increased risk of cancer and other health problems in them and their children constituted an injury under the law That ruling on risk has been consistent throughout most, if not all, DES litigation, as well as other lawsuits over toxic substance exposures.

The DES law suits join those filed by victims of exposure to other hazardous substances such as asbestos, radiation, pesticides or chemical wastes.

But the judge did sustain their claim charging the university with battery (legally defined as the unauthorized touching of the person of another), noting that the university’s administration of DES without the consent, or even knowledge, of the participants did constitute an “offensive invasion of their person(s).” In February, 1982, the university settled out of court, agreeing to pay the three women $225,000 and provide health monitoring for the children exposed to DES in the experiment.

The women in the DES lawsuit are among the rapidly growing number of Americans who have attempted to win compensation for their unwitting exposure to hazardous substances. In legal jargon, these personal injury lawsuits have become known as “toxic torts,” and such litigation is pending in most, if not all, court jurisdictions around the nation. The increase in the volume of lawsuits–and mounting pressure from those who have been exposed but cannot obtain compensation–have touched off a movement to reform the traditional common law system to ease the legal obstacles impeding the toxic tort victim.

The movement is an appealing one politically and emotionally. For it to succeed, however, a fundamental question first must be answered: Are large numbers of victims with valid claims of injury being denied equitable treatment under the existing system of common law? Or, as critics of the reform effort allege, is this simply a politically attractive solution in search of a problem?

Unarguably, the courts already have made some accommodations for the toxic tort litigant. But those changes have been slow in coming. More important, they have been inconsistent from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, giving rise to a situation where one victim can press his claim before a judge or jury, while another cannot even get through the courthouse door to file his petition. This, argue the reformers, perpetuates a system that is extremely unfair and thus warrants change.

That comes as no news to hundreds of the nation’s DES victims.

A Philadelphia jury in 1982 awarded a 21-year-old DES victim $2.2 million in damages against E. R. Squibb & Sons, Inc., concluding that the drug company was negligent in not adequately testing DES before marketing it. A Michigan jury, hearing almost identical evidence about early DES testing by another drug maker, found in 1980 that Eli Lilly & Co. was not negligent and dismissed the DES victim’s lawsuit. A Florida DES victim whose suit against Squibb was dismissed in 1979 because the state’s 12-year statute of limitations had expired successfully appealed the decision to the Florida Supreme Court. The court noted that because of the long latency period between exposure and manifestation of the injury the existing statute unconstitutionally barred her right of access to the courts. Yet a Michigan appeals court rejected a DES lawsuit in 1980 because the statute of limitations had expired.

The inequities of the existing system have not been lost on Patsy Mink, now a member of the Honolulu City Council, who has had recent first-hand experience with the vagaries of the law as it pertains to toxic tort victims. In this instance, her daughter currently is suing Lilly and the University of Chicago for $1 million in damages. The existing system, Mrs. Mink asserts, is “unfair and terribly inequitable.”

The “vitamins” taken faithfully by Mrs. Mink and the other participants in the 1951-52 Chicago experiment were, in fact, DES, a cancer causing drug that was tested on pregnant humans before it was ever tested on pregnant laboratory animals. Although scientists at the time believed a drug would not cross the placental barrier to affect the fetus, the medical community had plenty of evidence that estrogens–natural and synthetic–were potent and potentially hazardous substances. In 1932, estrogenic hormones were linked to cancer in mice, and in 1940 the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association warned in an editorial, “It is hoped that it will not be necessary for the appearance of numerous reports of estrogen-induced cancer to convince physicians that they should be exceedingly cautious in the administration of estrogens…”

Those warnings, and a lack of substantive medical data to back up the glowing claims of the benefits of DES did not dampen the popularity of the drug among many doctors, who believed it would help women with problem pregnancies carry their babies to full term. DES was being extensively prescribed to treat everything from mild cases of morning sickness to heavy intrauterine bleeding. Its leading proponents, Drs. George and Olive Smith, a husband and wife research team with impressive Harvard University training, even boasted that massive doses of DES “rendered normal pregnancies more normal.” Another leading proponent proclaimed, “We can give too little stilbestrol (a form of DES) but we cannot give too much.”’

(Studies have shown that it was the timing of DES ingestion, not dosage, that produced health problems in offspring. The most severe problems, including cancer, were reported in children whose mothers began taking the drug very early in the pregnancy. Although the mean total DES dosage prescribed in the Smiths’ widely followed regimen amounted to 11,913 milligrams, cancer has occurred when the dosage was as low as 135 milligrams.)

Between 1947 and 1971, an estimated 4 to 6 million people–mothers and their unborn children–were exposed to DES, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. A large percentage of those people today carry some physical imprint of that exposure.

The experiment conducted on Mrs. Mink and the other women at Lying-in Hospital was one of several at the time. A Tulane University experiment concluded that DES mothers had more premature births and smaller babies than mothers given placebos. These experiments by no means represented the death knell for DES, however. The drug retained much of its popularity for another full decade and was prescribed by doctors who either were unaware of, or disregarded, the growing body of medical literature warning about the hazards of DES as well as its ineffectiveness.

Unexpected Legacies

Then, in the late 1960s, doctors began to see cases of an extremely rare form of vaginal cancer in young women. In eight reported cases from New England, seven young victims had been exposed to DES during the first trimester of pregnancy. The number of cancer victims around the country eventually grew to approximately 350. One quarter of them died.

Doctors also have discovered other unexpected legacies of DES exposure:

A high percentage of the so-called “DES daughters” have malformed reproductive systems and glandular abnormalities knows as adenosis. These problems mean that many DES daughters experience fertility and pregnancy problems–ironically, often the same conditions that led their mothers to seek medical help a generation previously.

A follow-up study conducted by the University of Chicago on mothers who had been given DES showed that these women faced an increased risk of breast and cervical cancer, a risk that some researchers believe may also threaten DES daughters as they grow older.

DES sons have a higher than average rate of testicular cancers.

Reports of birth defects in DES grandchildren have begun to appear, causing researchers to question whether the legacy of DES will touch yet another generation.

The first DES lawsuit was filed in New York in 1974, and hundreds have followed in jurisdictions all across the country. The DES lawsuits join those filed by victims of exposure to other hazardous substances such as asbestos, radiation, pesticides or chemical wastes. All the victims are seeking compensation from those responsible for exposing them. But, they have discovered, the legal obstacles standing in their way frequently are overwhelming.

Those obstacles are inherent in the very nature of the toxic substances themselves. Injuries often do not appear until long after exposure. The latency period for many substances can be 20 years or more. (The cancer in DES daughters began to appear 12 to 17 years after birth.) After two decades, it can be difficult or impossible to identify the responsible product or manufacturer, especially, as in the case of DES and asbestos, where hundreds of companies were involved.

Cause Of Cancer

An even more onerous task is proving the cause of the injury. A victim of cancer, for example, may argue that the disease was produced by years of living near a chemical waste site. Yet, because the cause of cancer remains a matter of much scientific uncertainty, proving the cause-and-effect relationship to the satisfaction of a judge or jury is extraordinarily difficult. For every expert who links the cancer to the years of exposure to the chemicals, the waste site owners can produce an equal number of experts linking the cancer to some other factor, such as diet or smoking.

Finally, the cost of bringing a toxic tort lawsuit is extremely high because of the vast amount of expert testimony such litigation requires. One lawyer who has handled a number of these lawsuits estimates that preparing and presenting them costs at least $25,000. The average victim cannot afford that expense out of pocket. Although many personal injury lawyers routinely accept cases on a contingent-fee basis (in exchange for about one-third of the final settlement or award), victims with small injury claims (and, thus, the potential for smaller compensation) are hard-pressed to find a lawyer to take their cases. Those seeking reform of the current system argue that these victims are effectively being barred from the courts as a result.

In an effort to cut legal costs by combining the expense of expert witnesses, a number of victims have attempted to file class action lawsuits, seeking damages on behalf of a group of women. Most courts have refused to allow that, contending that the nature and extent of the individual victims’ alleged injuries are too diverse to permit creation of a “class” of plaintiffs. But, as with any other issue in DES litigation, that view is by no means unanimous. A Massachusetts federal court agreed to allow a class made up of the estimated 3,000 to 3,800 DES victims in the state; a Michigan court currently is considering whether to permit a class action lawsuit involving about 180 women to proceed in that state. The Illinois court hearing the lawsuit filed by Patsy Mink rejected a request for class status for the women in that DES experiment.

Courts around the country have attempted to respond to some of the legal problems. In a few cases, judges have eased the burden of proof for the victim by innovative applications of the law. Others have rejected innovation, and as a result, the victim’s request for compensation. These disparities are most glaring in DES litigation because, unlike other toxic tort lawsuits, the factual situations involving exposure of the victims often are almost identical. “What makes the DES litigation so troublesome is that courts are reaching flatly inconsistent conclusions of fact while examining essentially the same documentable series of historical events,” observed Sheila L. Birnbaum, a New York University law professor who has studied DES litigation.

Consider the following cases:

Dorothy Bichler took DES in 1953. In 1971, her daughter Joyce, aged 17, developed vaginal cancer and underwent radical surgery. Bichler sued Eli Lilly & Co. seeking $30 million in damages. Mrs. Bichler was unsure who manufactured the drug she took, and a New York State Supreme Court jury in the Bronx found that Bichler had not proven that it was Lilly’s product. The jury went on to consider a second issue raised by her lawyers. They argued that companies making DES had worked together jointly to obtain federal Food and Drug Administration approval of the product in 1941 and had as a group not adequately tested DES for possible negative health effects before it was widely marketed. Thus, even though Lilly may not have manufactured the actual product that caused Bichler’s cancer, the company’s actions in the overall industry effort to place DES on the market made Lilly just as liable as if it had made the pills. The jury awarded Bichler $500,000 in 1979. New York appellate courts have upheld the so-called “concert of action” theory of liability established in the case, noting that “there was evidence in abundance of conscious parallel activity by the drug companies…”

In Massachusetts, however, a federal judge hearing a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of all DES daughters in the state considered identical evidence about the early activities of Lilly and the other drug makers to win FDA approval of DES, and rejected the “concert of action” theory. In 1981, Judge Walter Skinner noted: “In my opinion, these facts do not even remotely suggest that the drug companies aided and abetted each other in marketing DES.” The California Supreme Court, in an appeal of a DES lawsuit brought by Judith Sindell against Abbott Laboratories and four other drug companies, viewed the evidence about the drug makers’ joint activities in an even different light, noting in 1980 that “parallel or imitative conduct” by drug makers is “a common practice in industry” and thus not a suitable grounds for holding the defendants liable.

The court in the Sindell case went on, however, to break legal precedent in DES litigation by creating a whole new scheme of affixing liability based on the manufacturers’ share of the DES market at the time the drug was taken. Sindell’s lawyers admitted they could not identify the maker of the DES in question. They also admitted that they probably had not sued every company that manufactured DES at its peak of popularity (an estimated 200 or more companies). In any other DES case those admission likely would have resulted in a dismissal by the court.

But the court majority noted that in cases such as this, “the response of the courts can be either to adhere rigidly to prior doctrine, denying recovery to those injured by such products, or to fashion remedies to meet those changing needs. California’s “market-share” liability theory–which would considerably ease a DES victim’s task of obtaining compensation–has not been adopted elsewhere. A New Jersey trial court embraced the concept in 1980, noting “wholly faultless plaintiffs should not be rejected because no other court in this state has as yet considered the legal questions raised against the factual backdrop we have here.” But the lawsuit was later dismissed in light of an appellate decision in another DES case that rejected “market share” liability because it imposed “’liability without fault.”

That does not mean that DES victims have been totally without redress in America’s courtrooms. The $2.2-million jury award to Judith Axler of Philadelphia is by far and away the largest. (The case will not be appealed under terms of an out-of-court agreement between Axler and Squibb.) Many other victims have reached settlements with the drug manufacturers for amounts ranging from $73,000, paid to the family of Victoria Bruck of Ohio, who died of clearcell adenocarcinoma, to several hundred thousand dollars.

Most of the DES cases that have gone to trial or been settled out of court thus far have involved young women with cancer. (According to federal statistics, the number of women at risk of contracting cancer ranged between 1.4 per 1,000 to 1.4 per 10,000 DES daughters.) For each cancer victim, however, there exist hundreds of DES daughters with reproductive abnormalities and adenosis, a glandular disorder that initially was believed to be a precursor to cancer, but now is generally regarded as being noncancerous. As a precaution, however, DES daughters are advised to seek frequent, extensive gynecologic examinations.

Rejecting Risk

A number of DES daughters with adenosis have filed lawsuits seeking compensation for their health problems and for facing the risk of cancer or other unknown health problems in the future. Few of these lawsuits have gone to trial. When they have, however, the claims routinely have been rejected by judges and juries on the grounds that a victim is not a victim merely because he or she faces an increased “risk” of injury.

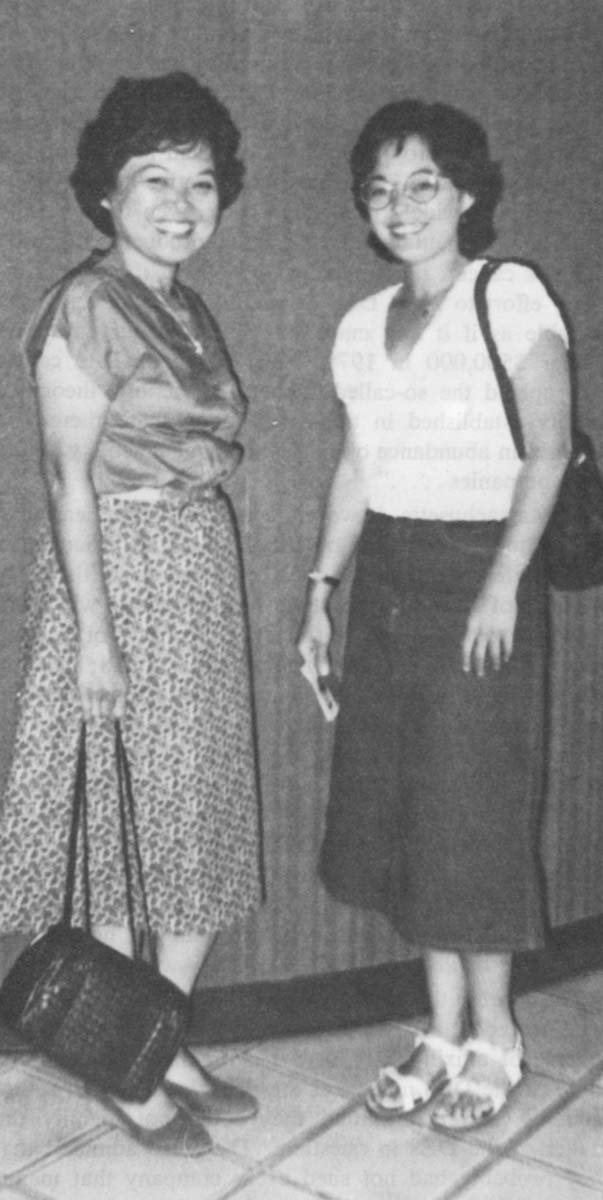

That was the finding in a lawsuit brought by Wendy Mink, the daughter born to Patsy and John Mink in 1952. Mink, a university professor in California, claimed her reproductive abnormalities were due to DES exposure and could increase her chances of having a problem pregnancy and contracting cancer. In March, a federal jury in Chicago rejected her claim. The case is being appealed.

Wendy Mink was confronted with a legal obstacle that has faced many other DES victims: a strict interpretation of the statute of limitations. Under Illinois law, she had only two years after discovering her health problems in which to sue. But the extent of her existing abnormalities and the fact that she could claim only an increased “risk” of more serious problems failed to impress the jury. The decision has angered her mother, who labels the verdict “an outrageous finding.”

“The jury said, well, it’s only a risk. Tough. You live with a risk. Your health problems may or may not happen, therefore it is noncompensable,” explained Mrs. Mink recently. “She had to file within two years and then she is told, It’s premature because it’s only a risk. You ask, Is this justice?”

No one bringing a lawsuit in the courts is ever assured of the outcome. Tort law never was intended to guarantee compensation for every injured person and the record is replete with inequities. But those who have closely observed the progress of DES and other toxic tort litigation through the court system argue that the scales of justice in these cases are heavily weighted against the victim. As a result, victims at least are owed a fairer opportunity to pursue their claims.

“We need to level the playing field,” commented U.S. Rep. Edward J. Markey (D.-Mass.) recently, in explaining the need for reform. Markey is the lead sponsor of a bill in the House of Representatives to do precisely that. His and several other similar hazardous substance victim compensation bills are pending in the Congress.

Although the measures vary in some details, they all provide for the creation of a federal administrative compensation system, somewhat akin to present worker compensation programs. Victims of toxic substance exposure could file their claim with the administrative system instead of in a court and take advantage of relaxed evidentiary rules on matters such as identifying the responsible manufacturer and proving the cause of their injury. In exchange for the relaxed rules, the victim would be eligible for a limited amount of compensation. The Markey measure sets the cap at $50,000.

No one knows the potential numbers of those victims, and that may prove to be the major sticking point to winning approval for some sort of reform. At a recent Congressional hearing on victim compensation legislation, Rep. Norman F. Lent (R.-N.Y.) repeatedly asked witnesses, including his colleague Rep. Markey, for hard data on the number of victims denied compensation. Markey and others supporting reform alluded to studies about victims but asserted that specific numbers as yet have not been compiled.

“I’m a little uneasy relying on an assumption that there’s a problem…,” observed Lent. I’d like to know a little more about this before we proceed with what will be a very substantial solution to a problem.”

Proponents of reform argue that waiting until better data is available will only ensure that the numbers of uncompensated victims will increase. Yet their assertions of a compelling need for new legislation are weakened somewhat by a lack of hard data.

Critics, sensing this weakness, consistently argue that the number of victims may be so small that it does not warrant a major reform of toxic tort law, at least at present.

Among the figures they use to bolster their contention is the federal estimate on cancer rates among DES daughters of 1.4 cases per 1,000 to 10,000 young women. Yet that figure ignores the far higher percentage of DES victims who have other abnormalities caused by the drug or may yet develop cancer. Significantly, they are the victims least able to obtain compensation for their injuries.

Finally, some would argue that numbers are not the most important motivation for reform. That point was compellingly made by Mrs. Albert Green, a Glencove, N.Y., mother who testified before a Senate committee investigating DES in 1975. “You know, if you take statistics, it is very meaningless unless that statistic is one of your own children.” Mrs. Green took DES in 1950 before giving birth to her daughter Susan. In March, 1969, at age 18, Susan died of vaginal cancer.

The legacy of DES and other hazardous substances that have been let loose in the environment represent a “ticking time bomb” for those exposed, according to Markey. “In some areas of our country, this time bomb has already gone off,” he told his colleagues. The victims of that explosion must not be denied fair compensation for the resulting injuries they unwittingly suffer. They will be, however, unless changes in the existing laws are made by the Congress, and the reformers pledge to press for those changes in coming months.

©1983 Susan Q. Stranahan

Susan Q. Stranahan, editorial writer on leave from the Philadelphia Inquirer, is reporting on victims of environmental poisoning and how they have been compensated.