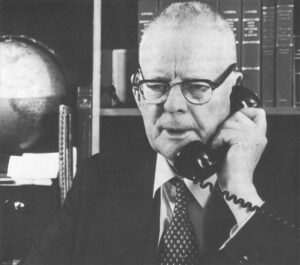

FALMOUTH, MASS.–At long, long last, W. Edwards Deming is a prophet in his own country.

Forty years after he first tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade corporate America to pay attention to the principles of statistical quality control, the 82-year-old retired federal government statistician has suddenly come into enormous demand. Around the country, and for that matter around the world, Dr. Deming has emerged as the guru of a “Third Wave” of industrialization based on the realization that careful, informed control of the materials and processes of manufacturing is an essential element for any business that wants to survive in the global competition for today’s markets.

Dr. Deming, consequently, has finally found an audience among his own countrymen. His four-day seminar here on Cape Cod this spring drew about 250 executives and engineers from places like Bell Labs, Western Electric, Prime Computer, and Digital Equipment who paid $795 each to hear the master explain the chief points of his basic text, Quality, Productivity, and Competitive Position.

It was the sixth Deming seminar this year, and from here the professor moved on to further classes in New York, Miami, Omaha, Washington, DC, San Diego, Johannesburg, London, and other cities. Those who miss the course can buy the videotapes, which are selling briskly at $6,300 per set. Those who want individual advice can join a long list of blue-chip manufacturing firms that have retained Dr. Deming as a consultant.

As Dr. Deming never fails to point out, the concept of “statistical control” is no more essential, and no more valid, today than it was in the 1940’s, when American executives spurned his lectures and turned their backs on his ideas. The only thing different now is that Americans have learned, the hard way, how powerful the Deming principles can be.

Just after World War II, under the auspices of the American occupation, Dr. Deming went to Japan and gave a series of courses to business executives there on the essentials of quality and productivity in manufacturing. Unlike the American audiences, the professor’s Japanese students took the lesson to heart and began to apply his teaching across the board.

“The Japanese businessman is never too old or successful to learn,” the crusty statistician says today. “Americans–you can’t teach them anything. An American businessman is afraid that if he asks questions, he’ll be considered unqualified…but the Japanese is afraid that if he doesn’t, he’ll miss something worthwhile.”

There is no single explanation for Japan’s post-war economic miracle, but the Japanese, at least, give a great deal of the credit to their American teacher.

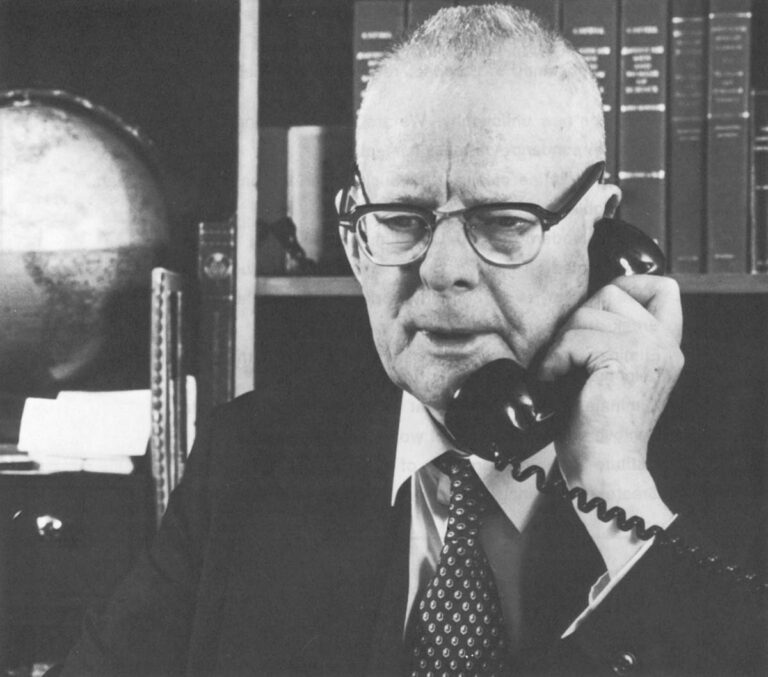

Dr. Deming is the only living American who holds The Second Order of the Sacred Treasure, Japan’s premier imperial honor. His name and profile adorn Japan’s Demingu Sho (“The Deming Prize”), an annual industrial award that carries the stature of our Pulitzer Prize. (The Deming Prize is presented to the proud winners each year during a nation-wide television broadcast somewhat like the Academy Awards.) Tens of thousands of Japanese factory workers, engineers, and executives study his books every year.

Made In Japan

When W. Edwards Deming arrived in the shattered world of post-war Japan, Japanese goods were everywhere considered cheap, shoddy products made from cheap, shoddy materials. Today, the label “Made in Japan” represents the world standard of quality for products ranging from steel, automobiles, and heavy machinery to cameras, scientific instruments, and electronic gear.

For American and European firms that used to control world markets in these fields, the transformation has been calamitous.

The experience of the American electronics industry has been fairly typical. Virtually all of the basic technology stems from American ingenuity; the central elements of the modern microelectronics revolution–the transistor, the semiconductor chip, and the microprocessor, or computer-on-a-chip–were all American inventions. U.S. firms still hold the major share of the $10-billion-per-year world market in electronic devices. But Japanese competitors have moved up so far, so fast, that U.S. firms have gone to Washington for help.

The Semiconductor Industry Association, one of the leading U.S. electronics trade groups, is asking the federal government to help combat what it calls unfair Japanese competition. The association says that predatory trade and pricing practices, together with massive Japanese government assistance, are responsible for the rapid growth of the semiconductor industry in Japan.

There is evidence to support these assertions. But there is also evidence suggesting that the Japanese moved ahead in semiconductor sales at least in part because they moved ahead in semiconductor quality. Some of the evidence was set forth in an infamous–or famous, depending on your point of view–meeting of electronics industry executives in Washington, DC in March, 1980.

Among the papers presented at the session was one that is known today as “The Anderson Bombshell.”

Richard W. Anderson, an executive at Hewlett-Packard, the Silicon Valley computer firm, spoke on his company’s experience with Japanese electronic devices. He explained that Hewlett-Packard began in 1977 to produce a computer that used Random-Access Memory (RAM) chips which store 16,000 digits of information. Such memory chips-known in computerese as “16K RAMs”–were invented in the USA. But American suppliers could not produce enough acceptable 16K RAM chips to meet Hewlett-Packard’s needs, so the firm somewhat reluctantly turned to Japanese manufacturers as an additional source of supply.

Although the point was not immediately obvious, Anderson reported, Hewlett-Packard gradually began to realize that there was a significant difference in the Japanese memory chips. They were far more likely than the American product to pass Hewlett-Packard’s standard factory inspection. And the computers in which they were installed went much longer without a memory failure than did comparable machines using American memory chips. In sum, Anderson said, the Japanese firms were producing higher-quality chips at about the same price as the American product.

In a narrow sense, this particular story may still have a happy ending for our side; Anderson says now that American suppliers have improved quality to the point where U.S.-made 16K RAMS are just about as good as the Japanese competition. In the current market for computer memories, in which the vanguard device is a 64,000digit chip (the 64K RAM), U.S. and Japanese manufacturers get roughly equal grades for quality from customers around the world.

But the larger message of The Anderson Bombshell was the Japanese firms had been able to do a better job than Americans in a complex technological field that was born and bred in the USA For those Americans who had been complaining that Japanese electronics firms relied on cheap labor, unfair trade practices, and government subsidies to get ahead, the Anderson findings–which were largely confirmed by other American computer makers–came as a stunning revelation.

One American who was not stunned, however, was W. Edwards Deming.

“I predicted in 1950 that Japanese manufacturers would come to dominate world markets and have their competitors crying for protection,” Dr. Deming says. “At that time I was the only person in Japan who believed that….But it was so simple. You could see that this society was receptive to the ideas that are necessary for quality and productivity.”

What Dr. Deming could see in Japan was a dedication to the job on the part of everyone involved in production–from the assembly line worker to the executives in the board room. “The Japanese employee has a sense of roots in the company,” he says. “There is a long-term attachment, so he can think about the long-term good of his company.”

Short Term Profit

“In this country, it’s all the short-term, the quarterly profit, the next 90-day appraisal. The American businessman is afraid to look beyond tomorrow because the bank and the stock market and the investors want results now. Why do you think [the American computer firm] Atari just laid off 1700 people? Not because they’re thinking of the future, when they could use a dedicated work force. It’s because [Atari’s parent company] Warner Communications and the banks wanted a profit right now….This is so wrong. It’s so obvious.”

For all his acerbic commentary on American ways of business, Dr. Deming is an old-fashioned patriot who spent much of his professional career in government service. After teaching engineering and physics at the Universities of Wyoming and Colorado in the early 1920’s, he earned a Ph.D. at Yale in 1927 and then took a job in Washington at the Department of Agriculture. He subsequently worked at the Census Bureau and taught at the Agriculture Department’s Graduate School. After his post-war consultations in Japan, he taught at the Business School of New York University. For three decades Dr. Deming has run a consulting business from the basement of his brick home on Butterworth Place in northwest Washington, DC

A tall, gruff, imposing gentleman with a fluffy white crew-cut and a jutting nose that gives him the look of a tortoise poking around outside his shell, Dr. Deming has arranged his life so that he frequently gets two days’ work out of a single calendar day. He takes a nap after he finishes a day of teaching, and at 8:30 p.m., where ever he may be on Earth, his secretary calls him to begin work on his private consultations. Asked recently whether he ever takes a vacation, the professor responded “Well, I’m not going to be doing anything for the next few hours.”

Still, Dr. Deming does find time for evenings at the piano with his wife, Lola, and their three children and seven grandchildren. He has been a member of church choirs all his life. He composes liturgical music, and his oeuvre includes two masses.

14 Points

There is a liturgical quality to Dr. Deming’s professional work as well. In his books and lectures he stresses time and again that the key to quality and productivity in manufacturing lies in certain fundamental rules–he has gathered them into a table of “14 points”–all of which can be summarized in a single, golden rule that should govern all work: “Do it right the first time.”

Crystallized in those six words, the Deming message seems obvious–a point the professor never ceases to make. “It’s so obvious,” he says in his lectures. “It’s so simple!” As the students here on Cape Cod found, however, the simple rules can become fairly intricate in application.

The 14 Points in Brief

Create constancy of purpose; reward improvement of product and service.

Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age.

Cease dependence on mass inspection.

End the practice of awarding business on the basis of a price tag.

Find problems

Institute modern methods of training on the job.

Institute modern methods of supervision of production workers.

Drive out fear, so that all may work for the company.

Break down barriers between departments.

Eliminate numerical goals, posters, and slogans that do not demonstrate methods for improvement.

Eliminate work standards that prescribe numerical quotas.

Remove barriers to pride of workmanship.

Institute a vigorous program of education and retraining.

Create a top management structure to pursue these points.

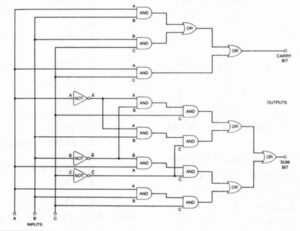

What Dr. Deming sought to teach in the seminar was the concept of “statistical control”–that is, careful, regular measurement of all aspects of a job. “By describing statistically exactly what is done,” he explained, “the method locates your problems, leads to innovations that solves them, and lets you measure your performance so that you can see new problems when they come up.”

The professor belittles the suggestion that “quality control” can be achieved by careful inspection. “Inspection is too late, don’t you see? It’s so simple! When you make toast, do you want to burn the toast and scrape it, burn the toast and scrape it–or do you want to make the toast right before it gets to your inspectors?”

The right way to make toast, under the Deming rules, would involve careful observation of every element of the process–the quality of the bread in the market, the wiring and the timing mechanism in the toaster, the methods employed by the person charged with making toast. If all these variables were tracked on a series of “control charts,” a manager could see what was happening just when any given slice was burned. The problem could be identified and corrected. The control process would be cheaper, more efficient, and far more productive than inspecting and scraping every piece of toast.

Another basic Deming rule is that “good quality does not necessarily mean perfect.” The proper goal should be a consistent, predictable range of quality throughout the production cycle so that goods can be produced at the lowest cost that will result in quality that is acceptable to the consumer. It would make no sense, that is, for a family to invest $5,000 in a toaster guaranteed to burn no more than one in a million slices. A failure rate of one in 500–that is, one burned piece of toast every three months–would be much less expensive to achieve but acceptable in most homes.

In his lectures, Dr. Deming leads up with great fanfare to the central lesson that predictable quality will enhance productivity. The reason–”It’s so simple,” the professor says–is set forth in two words: “less rework”. The time and money previously spent on inspecting and scraping burnt toast can be directed to a more productive goal–making more toast–once a predictable level of toast-making is achieved.

Moreover, it is cheaper to make one piece of toast right than to burn one piece, inspect it, reject it, and then make one right. “The total cost to produce and dispose of a defective item exceeds the cost to produce a good one,” Dr. Deming’s text says.

He cites the case of a beer manufacturer who told him that defective cans were “no problem” at the brewery because the can supplier replaced for free any faulty cans found. “It had not occurred to him that he is paying for the defective cans, plus the cost of halting production and replacing cans. It had not occurred to him that his customers are footing the bill with higher prices which may well be a cause of loss of market.”

It is the fear-and in many cases, the reality-of lost markets that have led American managers to pay tardy attention to the Deming message. To Dr. Deming, that in itself is a positive sign, because “no significant change occurs without the complete involvement of management.”

For all his criticism of American manufacturers, Dr. Deming has only praise for the American working man and woman. “The person on the assembly line has always been interested in quality,” the professor says, “because he knows that quality means jobs. Management is all wrapped up in the quarterly profit or the next stock offering or the fear that somebody is going to take over the company and fire the managers.”

New Age

Today, though, American management clearly is “interested in quality”–if it were not so, Dr. Deming would not have to squeeze two work days into one. The reason is that U.S. business has come to recognize, as Dr. Deming puts it in the “14 points”, that “We are in a new economic age. We can no longer live with commonly accepted levels of mistakes, defects, material not suited to the job…failure of management to understand their job…”

This new economic age has been called the “Third Wave” of industrialization, following from the First Wave at the start of the Industrial Revolution and the Second Wave that came in 80 years ago with techniques of mass production. The Third Wave, suited to a world with higher standards and a clearer recognition of limits, focuses on the most efficient possible use of resources to produce goods of predictable quality and reliability. The world-wide economic struggle among manufacturing nations today is, to a large extent, the struggle to stay atop that third wave.

What are the prospects of U.S. business in this global competition? W. Edwards Deming says the answer depends largely on how Americans respond to international competition. “If they want government protection, if that’s what they put their time into, they cannot succeed.” he says. “What they want is protection for inefficiency. They like it, apparently. But customers do not.

“The way for this country to fight back is to promote efficiency, to practice it, to produce goods of better quality than anybody else is producing. This can be done, if our industries are willing to do it. This is the only way to win an economic competition. It’s so simple. It’s so obvious.”

©1983 T. R. Reid

T. R. Reid, national reporter on leave from the Washington Post, completes his investigation of the U.S. semiconductor industry with this issue.