(SHUNGNAK, ALASKA) – “We are going out hunting tonight, hunting muskrats, beaver, whatever. You want to?” Jamie Commack sat up in a makeshift canvas tent in front of his parent’s cabin. “Let’s go ask Greg if we can use our boat.”

“Take 30-30,” suggested Vernon Douglas, crawling out of the tent after Jamie. “Yeah, 30-30, 30-40,” he laughed.

Jamie walked quickly toward the cabin. “Let’s go get ready, Niqi,” using Vernon’s Eskimo name.

Jamie and Vernon are Eskimos, just completing the eighth grade in Shungnak, Alaska. Jamie is the youngest son of James and Buelah Commack. James is mayor of Shungnak; Buelah is school cook. Vernon is the son of Vera and Leonard Douglas, local Alaska Fish and Game Department representatives. Today, Jamie and Vernon are hunters.

Preparing for the Hunt

“I’m not going to shoot with no gun that’s got a shell sticking out,” Vernon gingerly toyed with the cartridge. “Uh oh, shell’s ruined.”

“It’ll shoot. Just the tip.”

“Ali! It came out!” Vernon exclaimed.”

“It’s all ready to shoot, huh?”

“Try check.”

Jamie shouldered the rifle and aimed across the cabin. “Boom!” He put it down. “I should get my other gun.” He went off in search of a 12-gauge shotgun. When they finally left, the pair had two shotguns, the 30-30 and a .22 caliber rifle. They were ready for anything from a rabbit to a grizzly bear, although mostly they were looking for muskrat and geese. They returned with one muskrat.

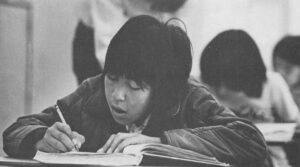

Math Ranks Somewhere Below Geese

“JAMIE! Stop talking to Calvin. Do your math.”

“CALVIN! Turn around.”

The sun shone in on the junior high math class at Shungnak school. A dozen students sat, some fidgeting, some working more or less quietly during the second period.

Jamie yawned, stretched. Vernon yawned. Outside it was a warm, beautiful day. Jamie chewed on his pencil.

“If you don’t hurry, you won’t finish today,” Jamie bent to his math and waited for 10:30. And then he waited for lunch. Then he waited for school to end, because math and social studies rank somewhere below geese and muskrats in the priorities of most 14-year-old boys in Shungnak. The test scores show it.

Standard tests given to students in fall and again in spring showed an average of no improvement in skills practically across the board for Shungnak’s junior and senior high school students. Some actually tested worse in the spring than they did in the fall.

Traditional Eskimo Education

Many parents in Shungnak strongly support education in principle. But in practice they welcome geese for supper more than algebra for homework. Many a father can tell his son the best lake for finding geese. But far fewer can uncomplicate differential equations.

To date, no Native in Shungnak has completed four years of college, though a few are now giving it a try. The 1970 census, the most recent accurate statistics, showed fewer than five per cent of the Eskimos 25 and older in this region have any education beyond twelve grades. Eskimo education has traditionally been at home and in the wild. To survive here, a family must know how to use the land. It’s not clear they need to know algebra.

In a remote village where the major “occupation” is subsistence hunting, where only two businesses operate, where job opportunities are usually limited to manual labor, the priorities don’t seem out of place.

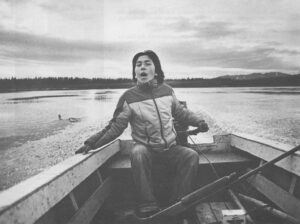

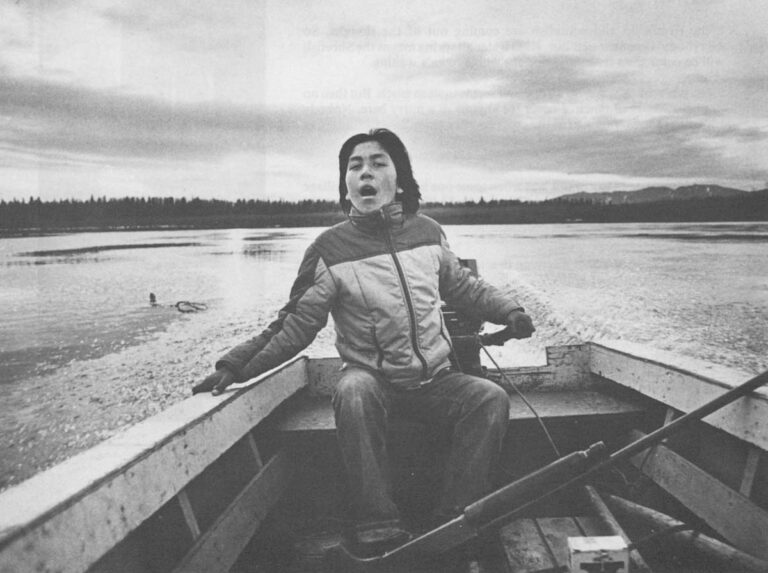

Hunting Ahaalik

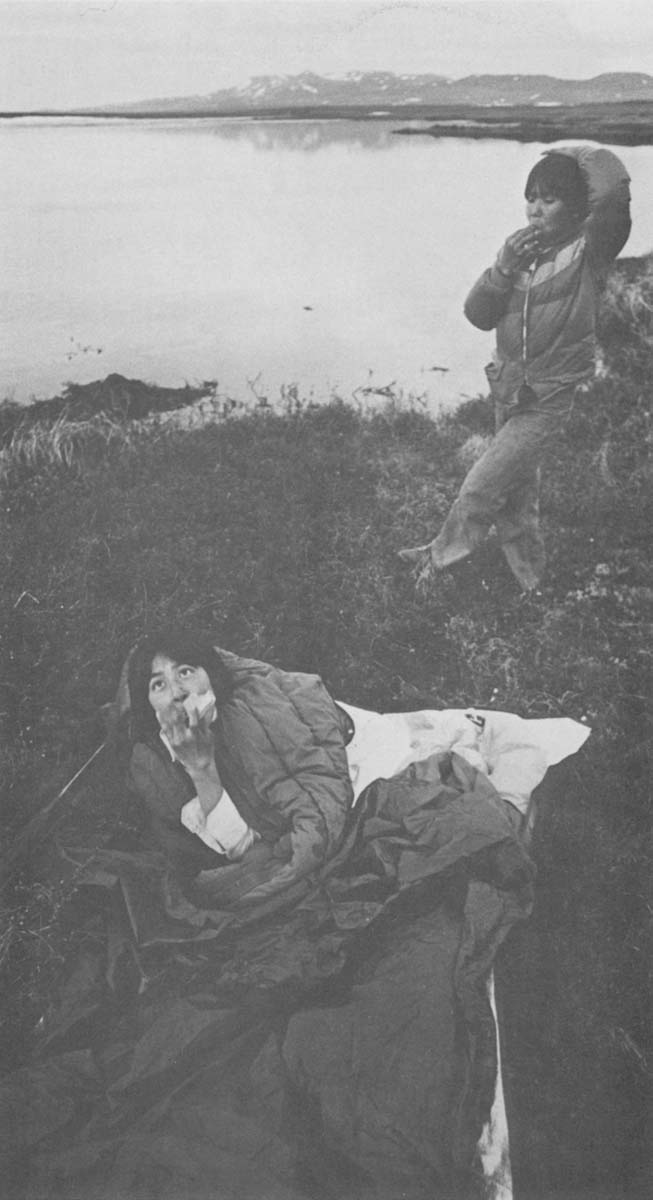

Sunrise came at 4 a.m., which mattered only if you were trying to sleep. Jamie and Vernon were not.

Vernon was off somewhere across the lake toward the mountains. There were ahaalik (old squaw ducks) over there; you could hear them calling, “aaaaa haaaa lik, aaaaaa haaaa lik.” Jamie half-lay, half-crouched behind a low mound of earth at the lake’s edge, waiting.

You could see for miles across the tundra, and the tundra was dotted with lakes. This is ideal waterfowl habitat, nesting grounds for thousands of North America’s migratory birds. Lush marshes support Canada geese, swans, ducks and countless other species. And the birds help support Eskimo subsistence.

Eskimos can hear geese long before the birds break the horizon, so keen is their hearing and so great is the quiet. And they can see them minutes before they wing into shotgun range, so sharp are their eyes and clear is the air.

“GEESE!”

Jamie hugged the earth and laid still. Soon, a pair of iksragutilik (Canada geese) came flying low and slow from the east, talking all the way. Jamie answered them with his own voice, changing the call, as they neared, not moving. But wary after weeks of hunters, the pair veered and continued west.

“They saw us, I think.”

“White Man’s Law”

Eskimos have hunted waterfowl in the spring for centuries, long before anyone in the South worried about stable migratory bird populations. But spring hunting is illegal now, so Jamie and Vernon and countless Alaska natives are breaking the law, “white man’s law.”

A few years ago, dozens of Eskimos in Barrow presented themselves for arrest with illegal spring ducks after one of their number was apprehended by a federal agent. The local magistrate refused to handle the cases, and since then the Alaska Department of Fish and Game does not actively pursue subsistence waterfowl hunters. Officials are trying to change the law.

The Eskimos seem to feel no remorse at breaking the law, only a little anger at the people who made it. They feel seasons are set for sport hunters who could buy a dozen fresh chickens if they needed to feed their families. White man’s law makes little more sense sometimes than white man’s algebra.

Vernon came back with one ahaalik.

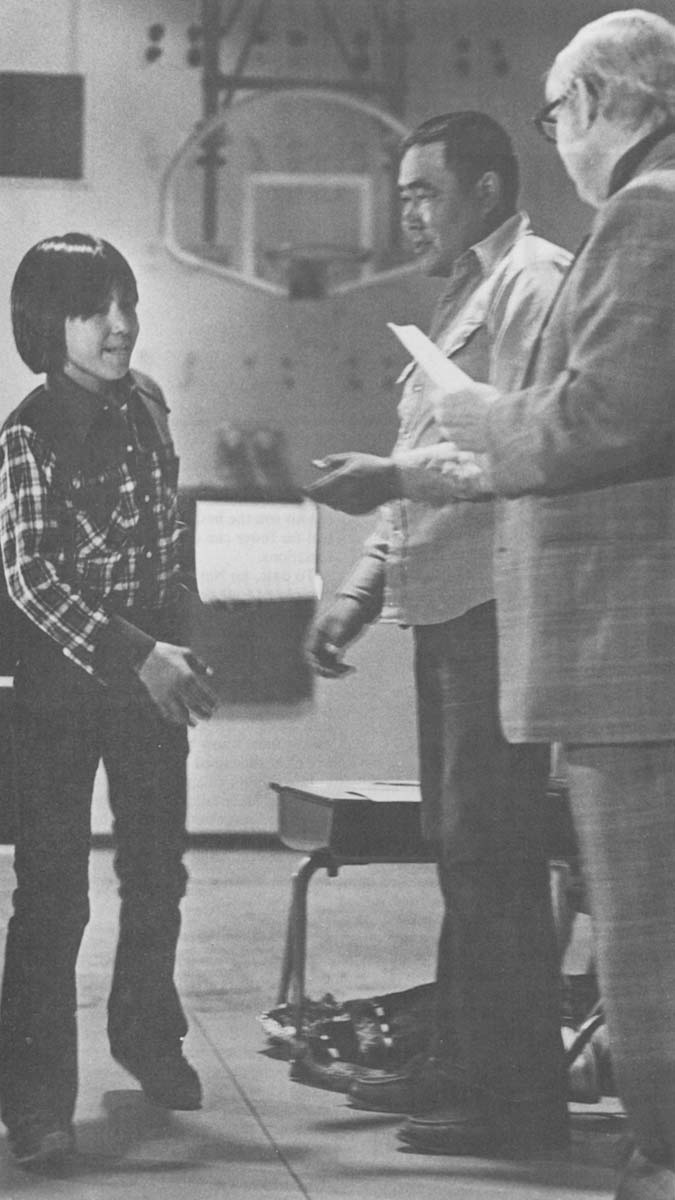

To Venture “Outside”

There is no lack of opportunity should an Eskimo teenager decide to venture Outside. Bureau of Indian Affairs grants will pay all the basic costs of his or her academic education. Other money is available for trade schools. Even transportation to and from the village can be arranged; Money is no barrier to the Outside for a Shungnak native.

There is no lack of opportunity should an Eskimo teenager decide to venture Outside. Bureau of Indian Affairs grants will pay all the basic costs of his or her academic education. Other money is available for trade schools. Even transportation to and from the village can be arranged; Money is no barrier to the Outside for a Shungnak native.

Jamie could go to college to learn practically any discipline, but only if he became a teacher or public administrator would Shungnak have any jobs to offer on his return.

Or he could learn to weld or plumb or build, though the trades are already well represented here. Any contractor faces more men than he can employ.

There is no Native doctor in the clinic, no native lawyer in the city office, no native engineer building roads in Shungnak for them to learn from. And there is no local counselor, other than harried schoolteachers, to give guidance.

So the two learn to hunt and fish, to live as their parents live. Both are good shots and excellent outdoorsmen, skilled at reading trails and signs. Both live for today and enjoy their world.

If you ask almost any Eskimo teenager what the future holds, they respond truthfully, “I don’t know.”

Via Satellite

It was a little past midnight Friday in Commack’s log cabin. On the television-beamed in from Anchorage via a satellite 23,000 miles above the equator-was Wolfman Jack, direct from London.

“Disco rock freak! Disco rock. Whoaaaa…” Wolfman howled. “Rock Freak. Rock FREAK. ROCK FREAK!”

“What’s this?” asked Jamie’s mother.

“Wolfman Jack,” answered Jamie.

“You brought me Giacobazzi?” asked the television.

“Jamie’s dad works in Galena, for BLM, fire fighting,” Buelah explained. On the wall of the cabin is a chart, showing the men of the “Galena Helitak Team.” James Commack is the heliport manager, a longstanding employee of the Bureau of Land Management fire crew. He spends his summers in Galena, 150 miles south of Shungnak by air, earning money to see the family through winter.

“That’s Elvis Costello,” someone interrupted.

“Hey, when you got it, you got it,” Wolfman Jack screamed. “Ladies and gentlemen, Peaches and HERB! On the second time around on the Midnight Special, how’s it feel, Peaches and Herb?”

“The Toyota is a heck of a car for these times,” the TV volunteered. “Am I pregnant? ACU test-at your drugstore now.”

“Jamie will make it,” Buelah said.

“The Minolta XD, the automatic choice for action photography,” Bruce Jenner said.

“Jamie will take Daddy’s place when he gets old,” Buelah said. Jamie watched TV.

©1979 Jim Magdanz

JIM MAGDANZ is spending his Fellowship year in Alaska reporting on Subsistence Living in a Changing Eskimo Village.

Jim Magdanz

Our Alaska correspondent, Jim Magdanz, was on the phone the other night trying to explain what life is like up in Shungnak.

“My 55 gallon drum is over half-full,” he said, “and the canoe has paddles anyway.”

“My 55 gallon drum is over half-full,” he said, “and the canoe has paddles anyway.”

“The river’s up and whitefish are coming out of the sloughs. So everybody’s got their nets out. High water all spring means the Sheefish will be coming up river early and the whole town’s waiting.

“The sun’s up. Always. So no one ever seems to sleep much. But then no one seems to need much. I never see anyone in a hurry here. Nobody runs except kids training for the cross country team.”

So, what’s the news?

“The biggest news in months was when some one broke into the village store in, the middle of the “night” and took $3,000 in checks. But the thief won’t be able to cash them, since they are all stamped ‘For Deposit Only.’

“Besides, if anyone does anything in a town of 200, every one knows about it in a matter of hours.”

Sounds like a poor place for a journalist, we mused.

“Shungnak? No, Shungnak doesn’t need a journalist. The people could survive with or without me.”

“If the world as you know it collapsed, Shungnak would survive. It would be difficult at first, but the Eskimos would survive,” he said, signing off.