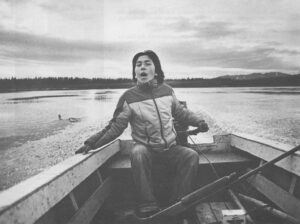

(SHUNGNAK, ALASKA) – The road to the new sewage lagoon runs through a blueberry patch. It’s a small matter. An acre of blueberries was traded for easy access to the lagoon and, coincidentally, to the rest of the blueberries. On a windy day this summer, you could often find village women and children hiking out the new road to gather wild berries for the winter. When their baskets were full, the road carried them home again to Shungnak, past the new school, past the telephone and television satellite dish, past the water and sewer plant and finally home to a new plywood and frame house. Supper was soon readyfresh moose and pilot bread, hot tea and wild berries with seal oil and sugar.

“If I were around when they were trying to put the sewer near the blueberry patch,” said Jenny Norris, the young Shungnak city administrator, “I would have been against getting the water and the sewer.

“If I were around when they were trying to put the sewer near the blueberry patch,” said Jenny Norris, the young Shungnak city administrator, “I would have been against getting the water and the sewer.

“But people didn’t reallv think about what they were getting into. They didn’t realize what the costs would be, especially for people who live in the housings. Bills are coming in airight for water and sewer. Most of them have been real good about paying their bills. But I know there are some people who won’t be able tor pay.”

In the past ten years, the federal government, the state of Alaska and private utilities have built more than $5 million in public works in this remote interior Eskimo village of 200 people. More than half the village residents are now living in federal housing, and nearly all subscribe to residential telephone service.

Ten Years Ago on Subsistence

Ten years ago, a visitor to Shungnak would have found a quiet and picturesque Eskimo village. It spread along a river bluff with mountains on every horizon. The tundra stretched for miles and miles. People lived five, ten or more, sharing 15-by-30 foot cabins. Villagers packed water from the Kobuk River. Kerosene lamps lit the night. The only regular expenses were propane for cooking, fuel oil for heating, gasoline for transportation and ammunition.

Family life was strong. Kids began packing water and chopping wood as soon as they were able. In summer the whole village was nearly deserted as families fanned out along the river to set up fishing and hunting camps to lay in a winter food supply. Worries were mostly about weather and hunting and fishing. Money was short, but people needed little. Those who were truly cash independent could chop wood for all their heat and run dogs for transportation. Clothing came from furs and some store-bought cloth sewn at home.

“I used to trap a bit,” said one villager, a man with a family and a new home. “But now for a couple years, I don’t have time to get out and set traps. I have to pay for my housing, pay for my telephone, pay for my electricity, pay for my stove oil, pay for my water and sewer.”

Their Fair Share

Like so many changes in Alaska, these in Shungnak can probably be traced to the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay. The land claims fight following the discovery led to a new awareness of bush Alaska by federal and state agencies. And Native leaders soon acquired the political savvy to fight for their fair share. Finally, there was new oil and tax revenue to deal with old problems.

In Shungnak, the changes began about ten years ago, when the Alaska Village Electrical Cooperative built a dieselpowered electric generating plant. That same year, the city of Shungnak requested a study to determine the feasibility of a water and sewer system. Eventually it was to cost taxpayers $1.6 million and serve 29 homes. Then the NANA Regional Housing Authority asked villagers if they wanted new frame houses to replace log cabins. Understandably, many villagers applied. Eighteen were accepted into an HUD housing subsidy program, at a cost of more than $1 million.

Independently of these local developments, in 1975, the Alaska legislature voted to revolutionize the state’s communciation system with a $5 million program to build satellite receiving stations in 100 scattered villages and towns. Now telephone and television signals from Anchorage are beamed to a satellite 23,000 miles in space and back to small earth stations. There is no comparable system in the world. Villagers watch ABC World News and The Incredible Hulk. They can dial direct anywhere in the U.S. The earth station in Shungnak cost approximately $100,000.

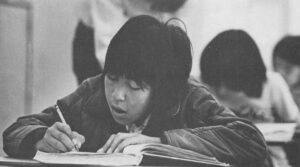

More recently, a young Alaska student named Molly Hootch sued the state because she was forced to leave home to attend school past the eight grade. The State Supreme Court ruled in her favor. So that Shungnak students would no longer have to travel 1,000 miles to Sitka, Alaska, or more thousands of miles to Salem, Oregon, to attend high school, a new $2.7 million school was built in Shungnak.

Paved With Good Intentions

The changes came from every direction, all at once, with no seeming logic, and evidently with all of the best intentions.

Whereas living in Shungnak ten years ago took very little money and lots of hard work, now it requires lots of money and lots of hard work. The problem now is there is very little work available in Shungnak. The government agencies built everything for the village except a viable cash economy. The largest employer is the school, with 10 Native positions, and there is neither industry nor opportunity for immediate development.

“In two and a half years, I have probably paid over $200,000 in wages,” said Fred Brown, the field engineer in charge of the water and sewer construction. “At full force, I employed 16 men.” But only one man has been retained, part time, to maintain the system.

“I did some figuring,” Brown continued. “I came out-without buying food-it costs the people $600 a month to survive. These houses probably cost $70,000 to build. They pay $50 to $150 a month. They used 100 gallons of fuel. That’s $140. I’m sure electricity bills run them a good $ 100 a month. Utilities for water and sewer costs them $50. That doesn’t include gasoline for hunting and fishing.

“They suffered a hell of a transition.”

“They wonder why the alcoholism and suicide rate is so high.”

“We did it. White man’s ingenuity.”

“I don’t see a future for Shungnak. I’ll be honest. I don’t see a future in white man’s world. I’ve lived in 52 villages from Pt. Barrow to you-name-it. Eskimo villagers are basically the same. They are subsistence. When they have that, they’re happy.”

A Dream of Gardens

Tony Schuerch is an Eskimo who agrees with Brown. Schuerch grew up downriver from Shungnak, went outside to school, and came back more determined than ever to live in harmony with the wilderness. His dream is gardens, to reduce Eskimos’ dependence on the outside for food. “We have millions of acres. If we can put a tiny fraction of that into horticulture, we’d be the best fed people on earth. We’ve got the high protein diet now. Take subsistence hunting and fishing, add to that subsistence farming, and we’ve got a diet that won’t quit. If we have a good agricultural base and we know how to preserve the food and distribute it, we can prosper.”

Tony Schuerch is an Eskimo who agrees with Brown. Schuerch grew up downriver from Shungnak, went outside to school, and came back more determined than ever to live in harmony with the wilderness. His dream is gardens, to reduce Eskimos’ dependence on the outside for food. “We have millions of acres. If we can put a tiny fraction of that into horticulture, we’d be the best fed people on earth. We’ve got the high protein diet now. Take subsistence hunting and fishing, add to that subsistence farming, and we’ve got a diet that won’t quit. If we have a good agricultural base and we know how to preserve the food and distribute it, we can prosper.”

Schuerch has been all over Northwest Alaska promoting his dream. He teaches hunters and fishers how to garden, sells them inexpensive seeds and donates roto tillers to interested villages. It costs very little initially. It costs even less to maintain. Gardening is high in return, he’s found, for a surprising number of vegetables grow incredibly well in the 24-hour sunlight of the Arctic. Even fertilizer can be locally produced, from the plentiful remains of fish caught for other uses. The only outside support necessary is gasoline for the roto tiller (even that is optional) and seeds.

Mauneluk

Another “subsistence” effort is being initiated by Mauneluk, a non-profit corporation concerned with the health and welfare of Northwest Alaska Natives, which is experimentally building a log cabin in nearby Kobuk. Using local labor and local materials, the cabin construction may prove to be a more logical alternative than plywood and frame homes shipped from the lower 48.

In Selawick, 150 miles away, a new sewer system is being considered that would provide each house with a self-contained disposal system. Engineers are discovering that expensive collection systems invariably freeze up. For instance, Shungnak’s sewer system didn’t make it through its first winter. “Eighteen hundred feet froze in March,” Brown said, “with more than 100 gallons of crap that’s not supposed to be in the sewer-towels, diapers, cloth. Took six weeks and $7,000 to clear.” While it was frozen, village sewage flowed across the tundra toward the blueberry patch. No one seems to know if Shungnak’s sewer system will make it through the coming winter, or the next winter, or the winter after that. Once one freezes solid in the winter, it’s usually frozen until spring.

Hunkering Down

Two brand new NANA houses stand empty, their owners working outside the village to earn money to pay bills. Several villagers are talking of moving out of the expensive new houses and back into their old cabins, at least part time. They would be nearer the river and farther from bills. Several families moved old wood stoves into their new homes to reduce the need for fuel oil. The new houses seem to require much more fuel to heat. The village actually ran out of fuel in March this year and had to airlift in emergency supplies.

One family decided to do its own redevelopment project. Napoleon Black tore down his small log cabin this summer, after planning for several years and ordering materials. The family was joined by volunteers from all over the community and built a new plywood and frame house, heavily insulated and solidly built. The project was in keeping with Eskimo tradition-a helping hand to those who need it. The Blacks will still be packing water and have no sewer. But they will have few bills and no mortgage.

One night, a third of the village gathered at Blacks to help move a trailer out of the way of the construction. It was heavy, and took some sixty people pulling on three strong ropes to pull the trailer up a small hill beside Black’s home. The spirit of cooperation was high. People seemed to regard it as fun, not work.

Meantime, those families who availed themselves of little or none of the government “assistance” seem to be doing quite well in Shungnak, still a picturesque village framed by mountains and surrounded by tundra, though not as quiet as before, with the diesel generator running 24 hours a day.

Life in the Arctic was never easy, but now it is probably more confusing. People ask themselves: Should I live in a new house or stay in the cabin? Should I look for a job outside, or should I stay here and set up fish camp? Will I have money to buy food and oil?

“We have been colonized,” Willie Hensley, the Native leader, says, “by the toughest possible political and economic system. We may have let too much happen too fast. But what could we do? It was like the Land Claim Act. We had to get on top of that wave and ride it or we’d go under.”

Tony Schuerch, the gardener, is more optimistic. “I’m sure the Eskimos are going to survive as a people, because survival is that thing we do best. We’re like moss on a rock, not very high, not very fast, but we sure hang on.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: The day this story was mailed to New York, Fred Brown returned to Shungnak with the news that the village of A mblerjust downriver had shut off its sewer system. Operation and maintenance of the lift stations proved too costly, he had heard, and he was on his way to investigate.

©1979 Jim Magdanz

JIM MAGDANZ is spending his fellowship year in Shungnak, Alaska reporting on Subsistence Living in a Changing Eskimo Village.