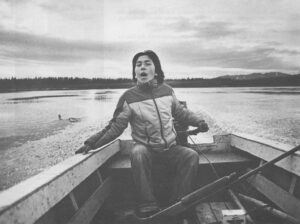

(SHUNGNAK, ALASKA) – Napoleon Black is a small man, made smaller by the vastness surrounding him. He was standing, quietly, sipping hot coffee. Before him, vapor still rising in the cold air, was a pair of lungs, a pool of blood and a bit of hair. Around him were the tracks of hundreds of caribou. One answered his rifle and stayed behind.

Napoleon Black is a hunter, good with a gun and tough enough to survive in a land few people ever visit. His home for sixty years has been Shungnak, a small Eskimo village on the Kobuk River in interior northern Alaska.

His land is a roadless wilderness, his water comes directly from the river, beautiful mountains frame his sunsets, wild animals roam free and-until recently were his for the taking.

Now, through no action of his own, he is being pressured by another world.

All of America wants Alaska. Congress is apportioning her resources. The state is struggling for her land. The Natives are choosing allotments. Private citizens want hunting rights and homesteads.

And of all the people who will feel the consequences of America’s decisions about Alaska, none will feel them more than the rural Natives like Napoleon Black. Scattered across the “wilderness” are thousands of American citizens-Athabascan Indians, Aleuts, Tlingit Indians and Eskimos. Some decisions could spell the end of their culture. And in some places, the native culture is running out of its own inertia. But not here. Not in Shungnak. Not yet. People here are too close to the old ways of subsistence. The Eskimo survives.

Levi Cleveland

Levi Cleveland just wants to be able to live here.

Levi is a large man, strong enough to swing a twenty-foot section of steel pipe over his shoulder single-handedly. He’s worked on the oil pipeline and in copper mines, seen a bit of the rest of the United States, and always comes home to Shungnak.

“In 1972, I went to Michigan for five days with the National Guard,” he remembers. “First time I’d been outside of Alaska. Five days was just about enough. This sergeant showed me quite a bit. I enjoyed staying there for the day.

“I’d rather stay in Shungnak. I was born here and was raised here. Everytime I go away, I can stay away about a month. But then I start feeling I’m missing things. Especially the food, I always start missing. I hunt ptarmigan, rabbits, fish.

“My dad lived halfway between Shungnak and Ambler. We lived off the land there. All we used to have was flour, rice, sugar, tea. If we didn’t have it, we lived without it for months at a time.

“We used to wake up in the morning and walk across the river to our fishing camp, chop a hole in the ice and fish for pike.

“Now the log cabin is collapsed. We still keep our fishing camp down there, and go down a week in the spring, then a couple weeks in the fall. That’s my type of life.

“Those parks, if they say what they do, like hunting will be open, trapping will be open, it shouldn’t be too bad. It won’t hurt much. If it’s going to preserve wildlife, I think it’s gonna be good.

“But if they’re going to restrict us from using it, I think it’s going to be a problem.”

Subsisting on Monuments

For the moment, regulations allow subsistence use of the national monuments created by President Carter in Alaska in 1978. Shungnak and Ambler, downriver, are nearly surrounded by the Kobuk Valley National Monument, the Gates of the Arctic National Monument and the Noatak National Monument. The National Park Service is drafting regulations that would continue subsistence use – hunting, fishing, trapping for personal consumption.

Levi Cleveland supports his family with subsistence and a government job. He works for the U.S. Public Health Service installing a new water and sewer system in Shungnak. So he can afford many of Shungnak’s new conveniences. His new house has oil heat, electricity, running water, television and a telephone.

But life here is expensive. Gasoline for boats and snowmobiles costs nearly $2.00 a gallon. Households using electricity only for light and refrigeration pay $50 to $100 a month. Fuel oil for heat costs $104 a drum and may last less than a month. People who don’t have jobs are hard pressed to afford the new life. Even those with work need subsistence food.

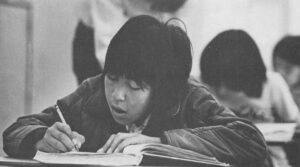

Florence Douglas is a bilingual teacher in the Shungnak school. She works part time teaching elementary children to speak, read and write Inupiat, the Eskimo language.

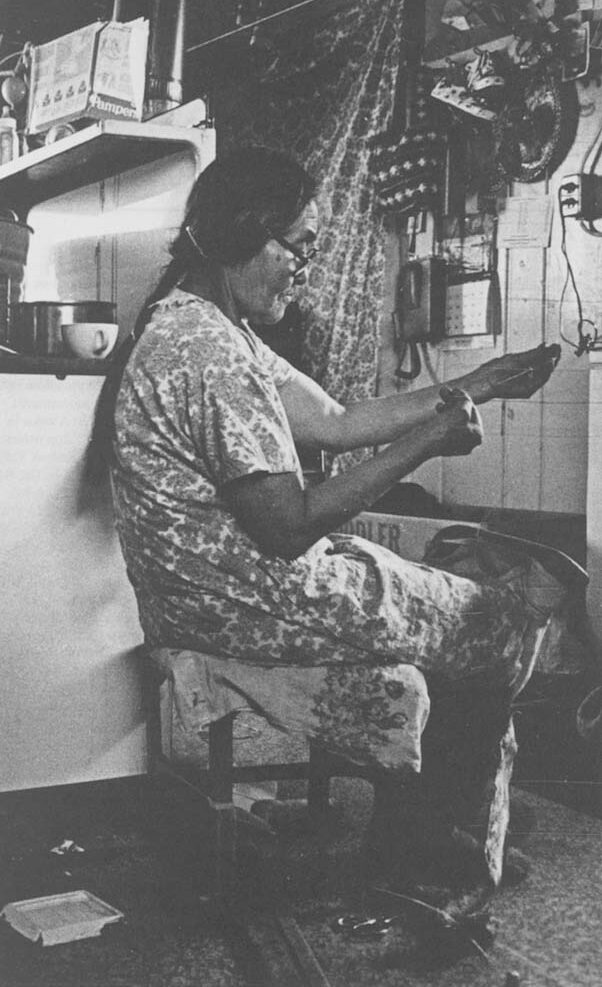

Her husband, Walter, is a subsistence hunter and trapper. Between them they support a family of eleven.

“Long time ago, when we used to go camping, fish camping, up the river, two or three months, school started late. We camped late, up the river.

“Only two or three families stayed in the village all summer. Now we stay all the time, even in summer. Last summer we just camp for a short time before school starts.”

“Long time ago, the whole family always go to the camps. But right now it’s different. Go out for two or three weeks. Before I got this job at school, I used to sew to earn a little money, sew and make birch bark baskets (which sold in Kotzebue and Anchorage as native handicrafts). But this year I didn’t make any baskets.”

The Douglas family depends on the fish they catch and the caribou they hunt. “When the game wardens make a limit for caribou, we ate chicken or hamburger. Before that, we didn’t buy chicken or hamburger because there was no limit on caribou. Caribou meat is real good. We buy those meats from the store just when we have no other meat.”

If she didn’t fish and he didn’t hunt, they wouldn’t have enough to pay for everything-oil, gas and electricity. It doesn’t take long to realize that there is one thing Shungnak depends upon: the land.

The Wilderness as Necessity

Eskimos here don’t see it as wilderness or mineral resources. It is their livelihood. They know and name every bend on the river and every mountain on the horizon. They use them. They depend on the game and fish as much as most Americans depend on paydays. They earn their living directly from the land.

In the debates over Alaska lands, one rarely hears about the subsistence use of the land. People in most of the country – though not in Alaska-don’t seem to realize how much the “wilderness” is being used to its utmost by people who’ve lived here practically forever.

Yet now Eskimo leaders worry about more and more outsiders seeking wilderness havens, and about the increasing Native population. Shungnak has been listed in most census reports as having 165 residents. A count of people living here this winter revealed more than 200. This means more game and fish are harvested.

“This region has 5,000 people, spread out in 11 villages in an area as big as Illinois, ” said Dennis Tiepelman, a native leader in Northwest Alaska. “We’re overcrowded. We’re overcrowding the resources.”

At the same time, the Western Arctic Caribou herd has been fluctuating. A few years ago, counts showed the population down drastically. Shungnak Eskimos and others were limited to one animal per person. It was a hard time then, for many people couldn’t afford store-bought meat.

Some blame oil drilling for the decline. Others think the count may have been in error. Still others point to historical fluctuations in caribou herds and say the decline was a natural phenomenon. Now, the herd population may be swinging upwards again.

For those who suspect oil exploration or drilling has an adverse effect on caribou migration and calving, though, the future is threatening. The herd’s summer grazing grounds are in Naval Petroleum Reserve Number Four. Congress is awaiting studies now being prepared to decide how to use the vast reserve.

And there’s more. More and more people outside the region seem to want to hunt Caribou: urban hunters on charter flights and even people from around the world on trophy hunts.

The Natives’ challenge is to protect their livelihood. So far they’ve been pretty successful defending their land, maddeningly successful if you’re a develop-Alaska booster. The land bill was largely the Native’s baby. It grew directly out of their own land claims settled in 1971.

The Natives are fighting still, this time to protect their use of the land they garnered in 1971. The battle cry is subsistence. And they have some important allies.

Zorro Bradley

Zorro Bradley is head of the Cooperative Park Studies Unit at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. He has been a ranger/ anthropologist with the National Park Service for many years. He commissioned an exhaustive study of subsistence in the Kobuk River Valley several years ago. And he’s sold on subsistence protection, even if his bosses are not.

“You have to fight off the [National Park] Service,” he says. “They’re already making plans for roads, visitor centers, picnic areas.” For remote Gates of the Arctic, he was asked. He nodded.

“Plans I’ve seen on the drawing boards frighten me, like access to areas through a village. I’ve seen what that can do to a Navajo village in the Southwest. Tourists walk into a hogan uninvited taking pictures…”

Indeed, Shungnak residents have heard that a ranger may be stationed in their village. It makes sense; they are close to the monument.

“The thing I’d like to see, if we can ever get it off the ground,” continued Bradley, “is to have the management handled by Natives. We have done that elsewhere, in and around the Navajo reservation in Arizona, New Mexico. We’ve done it in Hawaii, also…”

Instead of picnic areas, he thinks the National Park Service should be protecting subsistence. “The whole National Park Service attitude has been wildlife management, not to regulate the continued taking of wildlife.

“Because of the situation right now, people in transition, subsistence should have high priority. Perhaps in 30 or 50 or 100 years, there will be no need for this. I would hate to see these people denied access. So much of their history is there.

“In the South, so little is known of the old ways [of the Indians]. But here you have centuries of knowledge. It’s in the minds of the people right now. Let’s keep it up there. We’re running out of time.

“There are people out there who can remember the first white man they saw, remember when rifles were introduced.”

The Natives’ plea for subsistence protection has reached the Department of Interior and President Carter. At Carter’s direction the Department is committed “to protecting the opportunity for rural Alaskans to engage in a subsistence lifestyle.”

A spokesman for Interior Secretary Cecil D. Andrus said, “Alaskans who truly live in rural villages and are dependent on local fauna and flora for their food should be able to continue to live from hunting’ fishing and gathering for their personal use.”

NANA

In Northwest Alaska, land-use decisions are partly controlled by NANA Regional Corporation, Inc. The largest landowner in the area except for the government, it was established in 1971 by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act to choose and administer native lands and to manage money paid Natives for land relinquished to the United States.

NANA President John Schaeffer is concerned. “We’re trying to protect subsistence. We can see no alternatives. Not even intensive mining. The adverse effects are worse than the benefits, at least for now. That has been the cornerstone of our land selection and management purposes.

“The only viable alternative to subsistence is welfare. To us, it is not a viable alternative. We don’t like welfare. It has a detrimental effect on persons’ personalities.

“We’ve tried to keep the villages’ subsistence. We try to provide village people with jobs in other areas. But we can’t find enough right now, since the pipeline.”

So Schaeffer joins Tiepelman and Bradley and Cleveland and Douglas. Without the sustenance the land provides, Shungnak would be in trouble.

The Choice

Two vital ways of life-urban, technological, energy-intensive America and rural, subsistence Alaska – may be becoming mutually exclusive.

To some, it’s a very simple matter. U.S. Representative Huckaby put it bluntly during committee hearings in Fairbanks this year. “Today, America imports 40 per cent of its oil. We’re heavily dependent on the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Shell Oil estimates 50 per cent of our oil reserves are in Alaska.

“It’s possible OPEC will cut off our oil. Are you willing,” Huckaby asked an environmental witness, “to cut off right now 50 per cent of your consumption of electricity, gasoline, oil…?

“We didn’t say a little. We said completely change your lifestyle…”

Huckaby wanted to allow oil exploration near the Porcupine Caribou Herd calving grounds in Northern Alaska, east of Prudhoe Bay. West of Prudhoe Bay is the Naval reserve, “Pet Four,” the summer grazing ground for the Western Arctic Caribou Herd that Napoleon Black and his fellow Shungnak Eskimos hunt. Congress already has commissioned a study of the possible uses of that reserve.

National Park Service biologist Sverre Pederson has been working with a team on that study. He’s graphically mapping local subsistence use of wildlife and plant life. He hopes the report will “give Congress a feeling for what life is like in the villages.

“Congress is going to have to make decisions,” he said, “about how to best use this reserve, how to integrate the uses so they will interact least harmfully with one another.”

Will the decision be in the interest of the several thousand hungry subsistence villagers or the millions of oil-hungry Americans? Can both be satisfied?

“If you eliminate the natural biological reserves locally available,” said Pederson, “you are destroying the people who live there. It’s that simple. It’s up to Congress.”

©1979 Jim Magdanz

JIM MAGDANZ is spending his Fellowship year in Alaska reporting on Subsistence Living in a Changing Eskimo Village.