(DENVER) – In early August, shortly after President Carter proposed his dramatic shift in U.S. energy policy-the federally subsidized production of millions of barrels of synthetic fuel per day from coal and oil shale-I was in Denver talking with people about water and how its relative availability or scarcity will affect the future of the arid Rocky Mountain and High Plains states. It is toward this region, of course, that the President’s new energy creation, in whatever form it appears after having been disassembled and rewired by Congress, will come lumbering, because most of the nation’s coal and nearly all of its high-grade oil shale lie roughly within a 600-mile oval in the states of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and Utah.

My first interview was with Alan Merson, who had just resigned as regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. Merson, an amiable, intense man with a disarmingly candid manner, is a former law professor and occasional tester of political waters; he upset Congressman Wayne Aspinall in the Democratic primary of 1972, but lost in the election to the Republican candidate, James Johnson. He had acquired a reputation as an unapologetic environmentalist during his tenure at EPA, and it soon became apparent to me that he must have been at war, especially over water, with almost everyone else in the state.

“Dick Lamm”- Lamm is the governor of Colorado-“is a perfect symbol of what’s the matter with this state,” Merson told me. “He was elected as an environmentalist, but then I think he got religion late in life-he saw that the great capitalist machine cranking out filth and ugliness and devastation was also making his constituents fat and sleek and happy, and he realized that, out here, the whole damned machine runs on the impoundment of water, so he thought, by God, we’d better impound some more water. His man Harris Sherman” -Sherman is Lamm’s director of natural resources–is the same way. He’s not big on industrial development, but he loves irrigated agriculture, and he shows how fast you can go from being a lawyer for the Environmental Defense Fund, which he was for a short while, to being a guy who never met a water project he didn’t like.” Felix Sparks, the head of Colorado’s Water Conservation Board (in the and West, the phrase “conservation of water” usually means capturing every available drop and putting it to some economic use before it runs out to sea) was dismissed by Merson as “an absolute disgrace”, and, he said, “the whole Congressional delegation, except for Pat Schroeder, is on the run from the water developers and irrigators-not even all the irrigators, but just that small bunch lucky enough to be out there sucking off the big federal teat.”

Kind Words For Everyone

Merson went on like this for over an hour, stopping every now and then to apologize for “character assassination” and then starting all over again. I had come to Colorado with visions of John Denver in his Rocky Mountain aerie, an environmentalist governor, an environmentalist Congressional delegation, and hundreds of thousands of people who had moved there only because it was one of the latest unspoiled places and everyone wanted to keep it that way-a state in which some sort of mystical harmony existed among the various citizenry, where the lion lay with the lamb-so I was rather startled by Merson’s diatribe. How could he be saying such things? Why was all this feuding going on?

Then I went to see Felix Sparks, the scowling, blustery head of the Water Conservation Board, and found him even more incendiary than Merson. I had hardly settled down in his office before he was complaining about the “goddamn bunch of jackasses in the EPA.” He told me that Merson, whom he called “an idiot”, ran “the most dictatorial agency, the most dictatorial body in the United States!” and that he-Merson-was the most powerful person in the state (Merson had just told me that Sparks was probably the most powerful person in the state). His sentiments about most of the state’s political leaders were at least as negative as Merson’s, except that he felt they were behaving in exactly the opposite manner than Merson had indicated.

Cursing Over Water

Sparks and Merson were an extreme juxtaposition, but there was obviously a lot of fighting going on in Colorado, and most of it seemed to be over water. As the days went on, I interviewed upstream farmers who cursed downstream farmers, ditch irrigators who cursed pump irrigators, East Slope Coloradoans who cursed West Slope Coloradoans, West Slopers who cursed East Slopers, boosters of industry who cursed boosters of agriculture and visa versa, water lawyers who spun conspiracies before my eyes, and environmentalists who, railing against nearly everyone, were in turn railed against by nearly everyone else. Even in my home state of California, where battles over water have been going on almost from the day the first white settlers arrived, and where so many sides are now fighting each other that the imperial alliances formed before the First World War had, by comparison, an infantile simplicity about them, I have rarely seen such intensity of feeling or levels of exasperation as I saw in Colorado.

The reason why soon became clear enough. California, despite its semi-arid climate, its 23,000,000 people, its huge industrial base, and its ten million irrigated acres, gets enough rainfall in the mountains and along the North Coast to allow nearly half of its water to run out to sea without having first been put to some purportedly beneficial use. What is more, nearly ail the rivers with their headwaters in California also empty into the sea in California, so all of their water belongs, in a legal sense, to the state. Colorado’s rivers carry only slightly more than one-fifth the annual run-off of California’s-the state is more and than many people realize-and they all cross into neighboring states which are mostly desert, so Colorado has to share a great deal of the water in its rivers wit], them. The result is that Colorado, second only to California in the arid West in population, industry, and irrigated acreage, has available for its use just over one-tenth as much surface water. Between the demands of agriculture, population, industry, and environmentalists not to mention the potential explosion in energy development- there doesn’t seem to be enough to go around.

Era of Limits

Easterners often blink uncomprehendingly when it is explained to them that the amount of run-off in rivers has generally been the key to population growth, prosperity, and development in the and West. The fact that Colorado has a permanently fixed quantity of only 7.7 million annual acre-feet (an acre-foot is 326,000 gallons) of surface water at its disposal, compared with California’s 70 million or so acre-feet, means that Colorado is approaching an era of limits much faster than the state whose incumbent governor popularized the phrase. The first principle of an era of limits is that, as resources become scarce, some means must be found to allocate them. The first means of allocation is usually price.

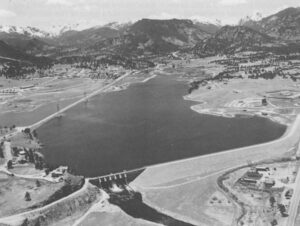

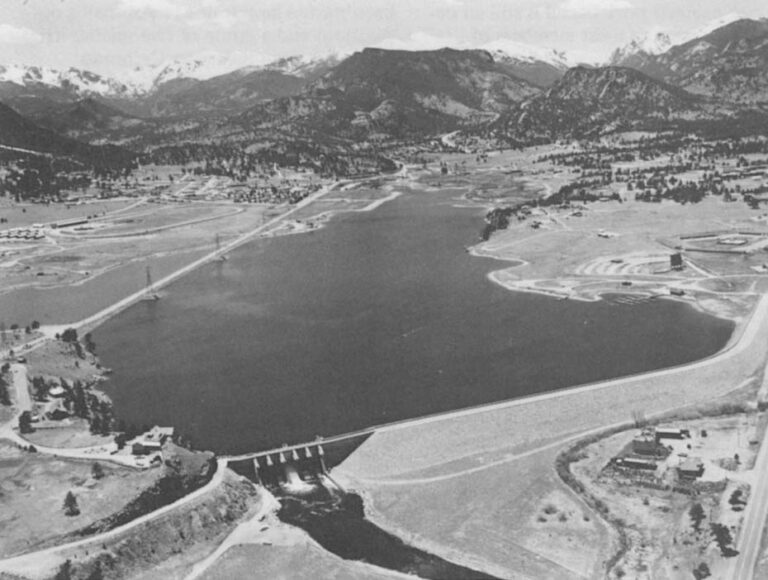

In 1947, the Colorado River, which had, by then, already had a number of unnatural acts performed upon it, was made by the Bureau of Reclamation to flow toward the Gulf of Mexico instead of toward its usual destination, the Pacific Ocean. The means of accomplishing this feat was the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, an engineering wonder which took several hundred thousand acre-feet of water per year out of the headwaters of the Colorado and piped it across the Continental Divide through a 13-mile tunnel underneath Rocky Mountain National Park. Irrigators along the Front Range could buy shares in the project for $40, each share entitling them to one acre-foot per year, and, in the following years, paid a few dollars per acre-foot toward the operation and maintenance of the project.

Those who bought the shares did the smartest thing of their lives. The growth of population and industry along the water-short Front Range exceeded anyone’s expectations, and today the same shares of Colorado Big Thompson water that originally sold for $40 are being sold for about $1700, a rate of appreciation matched by only a few items in contemporary American life-perhaps Xerox stock certificates, New York City taxicab medallions, or certain Washington, D.C. or Beverly Hills, California real estate. (One must note, in passing, the irony in this: the construction of Colorado-Big Thompson was heavily subsidized by the American taxpayers, who assumed-as they do with all Bureau of Reclamation enterprises-the interest obligation on the entire irrigation component of the project, and by the purchasers of the hydroelectric power it generates; without such subsidies, it is unlikely that the project would have been built at all, and young retired farmers who inherited good water rights would not be buying Winnebagos and moving their families to Fort Lauderdale.)

Forty Times What They Paid

Meanwhile, on the other side of the state, there are strong indications that energy companies are quietly purchasing water rights from irrigators and leasing them back until they need the water. Through such an arrangement the contract need not be recorded and its very existence, along with the price paid for the water, can be kept secret, but the general feeling seems to be that farmers are selling water for ten to forty times what they paid for it-thanks again, in part, to federal subsidy.

From an economist’s point of view, and perhaps even from the point of view of certain environmentalists, all of these developments are a good thing. They mean, first of all, that water is searching for its highest use, which encourages efficiency and maximizes (to use that economists’ verb) the economic benefits obtained from each unit of water. And, since irrigated agriculture is far more water- consumptive than any other use-it currently accounts for between 80 and 90 percent of all water consumption in Colorado, but returns a much smaller fraction of the state’s income-it means that economic growth need not have as its price the damming of every riparian wetland, and the flooding of every beautiful river valley in the state.

However, water use in the West has never been a matter of mete economics. Much more, it has been a matter of politics. Colorado is no exception to this rule; it is, in fact, almost a paradigm of it. No better illustration of this fact exists than was provided by Colorado’s contribution to the Carter Administration’s so-called water projects hit list.

The hit list was a group of nineteen authorized water projects which, the President announced in 1977, he wanted to terminate on the grounds that they were too expensive, wasteful, and destructive of the environment to merit continuation. (Carter was blown head over heels by the reaction to his announcement, which proved that the water projects pork barrel is still an object of veneration to most members of Congress.) Of the nineteen hit list projects, five were in Colorado-an achievement matched by no other state, and a pretty good indication that Colorado had somehow become America’s wonderland of water development. Even such impregnable bastions of pork barrel politics as Tennessee, Mississippi, and Oklahoma were left behind.

The Wizard of Water

Every wonderland needs a wizard, and in Colorado’s case it was Congressman Wayne Aspinall, a crusty political genius who was chairman of the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee throughout much of the 1960s. What Aspinall did was both brilliant and simple. In 1922, the waters of the Colorado River and its tributaries had been apportioned among the upper basin states (Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico and Utah) and the lower basin states (California, Nevada and Arizona). California, which was growing at a phenomenal rate, quickly diverted its entire apportionment and the unused portion of Arizona’s toward the Imperial Valley and Los Angeles. Within a couple of decades, Arizona was growing nearly as fast as California and already over-drafting its groundwater, so it began to lobby strenuously for the project which had, for many years, been the gleam in its eye: the Central Arizona Project, a scheme of truly Herculean proportions which would hoist its Colorado River water over the Black Mountains and send it into the populated central part of the state.

Colorado, whose Colorado River allocation was the next largest behind California’s, didn’t really need to begin developing its apportionment until later. But it became extremely uneasy watching the blooming deserts and sprawling cities of its and neighbors to the south, and wondered whether, in a crunch, they might not have the political power to rewrite the Colorado River Compact to their advantage. At the same time, according to Clarence Kuiper, the recently retired Colorado State Engineer, the Bureau of Reclamation-which is always looking for something new to build-began raising the specter of prior appropriation, the terrible “use it or lose it” imperative that has always haunted the West. If you don’t let us build you some projects so you can start using your water, said the Bureau to Colorado, you might lose that water to California and Arizona.

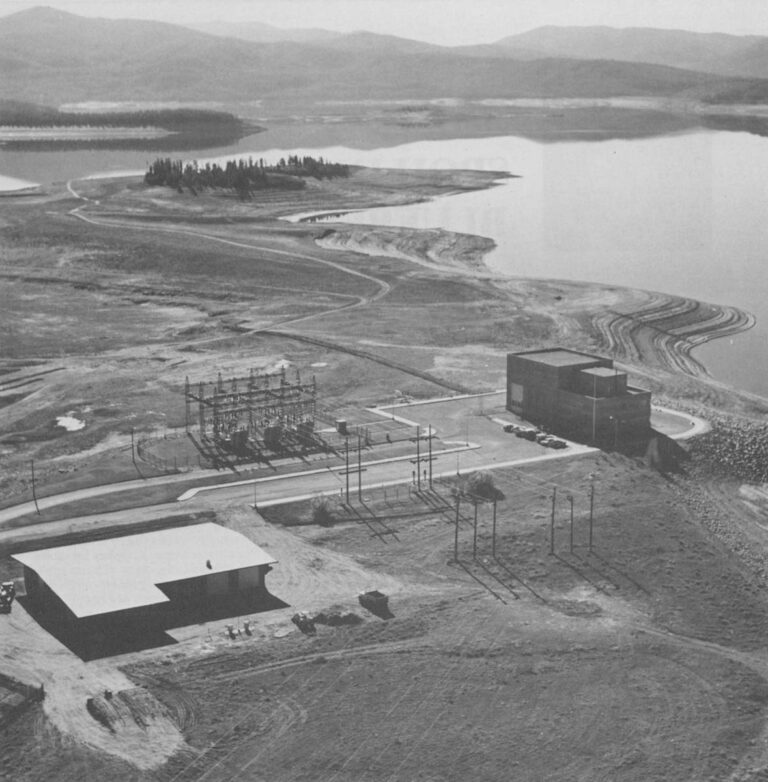

Finally Aspinall decided that it was time to do something. Together with Floyd Dominy, the then Bureau Commissioner (and a brilliant politician and inveterate dam-builder), he cooked up a deal with Arizona. The Bureau would build both the Central Arizona Project (which had not been started largely due to Aspinall’s opposition) and a group of five smaller irrigation projects in the upper Colorado basin all of which were located, coincidentally, of course, in Aspinall’s district. What is more, the Arizona project and the Colorado projects would have to be completed at the same time. It was a clever move on Aspinall’s part, because many people, including Kuiper, were rolling their eyes over the Colorado projects, which would consume a great deal of water irrigating very few acres and subsidize some farmers to the tune of several hundred thousand dollars apiece. (The Bureau now says-having corrected its two million acre-foot overestimate of the flow of the Colorado-that the five projects, together with several other Aspinall-inspired projects which were authorized later, could also use up Colorado’s entire remaining apportionment from the river.)

With a provision thrown in that nobody was even to think about diverting water from the Columbia River to the parched Southwest-that was there to mollify Senators Henry Jackson and Warren Magnuson, who had been hearing too many suspicious rumors-the Colorado River Basin Project Act was ready for the President’s signature, and, in 1968, it became a part of the body of enlightened legislation which issues forth from the United States Congress.

Interviewing Aspinall

I visited Wayne Aspinall in August at his home in Palisade, Colorado, on a bluff overlooking the Colorado River, and asked him if he was embarrassed by the fact that most of the water projects he championed had been on the Administration’s hit list. His answer was absolutely not, they were good projects. I then asked him if it made sense to tie up so much of Colorado’s scarce water in some irrigation projects which will contribute virtually nothing to the nation as a whole but which might inhibit future growth in other parts of the state, not to mention their effects on the environment. His answer was essentially that Colorado is first and foremost an agricultural state, and that there would be plenty of water in the future for everyone.

But others are not so sure, and the display of emotions I had seen earlier in Denver makes me believe they are right. Surface water is, in fact, already being spread too thin; in some areas, farmers were devastated by the recent drought because there was too little emergency storage. The cities on the Front Range, which contribute far more to the state’s prosperity per acre-foot of water consumed than marginal irrigation on the West Slope, could bring more water across the Divide and could certainly use it, but this option may be circumscribed if the West Slope projects are built and the Colorado River entitlement is used up. Even the production of oil shale requires much less water than irrigated agriculture, and it might contribute significantly to the nation’s security; while there appears to be enough water in the immediate vicinity to supply a 400,000 barrels per day shale oil industry, if the OPEC nations were drastically to tighten exports and we decided to develop the industry to its full potential of perhaps 2-3 million barrels per day, there could be too little water storage in the right places, and too much in the wrong places, to support it. A substantial part of Colorado’s economy is maintained by tourism, and many tourists visit the state wanting nothing more than to fish in a mountain stream in the middle of an unspoiled mountain valley, but Colorado’s continuing obsession with irrigated agriculture will leave them with fewer and fewer valleys to visit, and with precious few streams that have much water left in them.

Something of a Mystery

There are large unused reservoirs of groundwater in Colorado, and the state may eventually fall back on them. But groundwater development has its own host of problems, not least of which are that it often causes land subsidence and depletes stream flows downriver; it has a nasty habit of creating bitterness, distrust, and lots of work for lawyers. In any event, the state is doing little about groundwater, and continues instead to follow blindly an archaic philosophy of water development, usually at the expense of many and for the benefit of few.

Why Colorado, a rapidly changing state with a predominantly urban population, should be behaving in this way is something of a mystery. It has a lot to do with the entrenched power of agriculture in what has been primarily an agricultural state; with the fact that there have been too many boom and bust periods in the past, making the state value, almost to the point of sacrosanctity, the stabilizing influence of an agricultural economy; and with a perennial desire on the part of Westerners to watch the desert bloom, an attitude which Mason Gaffney, a professor of economics at the University of California at Riverside, refers to as an “atavistic cultural twitch”.

There is a certain pathos in the spectacle of a state where water has always been scarce, blindly continuing policies, which will rapidly bring it up to the absolute limits of its water supply. However, Colorado can only afford to give 80 or 90 percent of its water to irrigated agriculture, at the expense of everything else in a coming era of shortages, if the federal government continues to build all the subsidized water projects the state asks for. Coloradoans seem to feel that they have a right to those projects, but, in this age of inflation and environmentalism, the rest of the nation no longer agrees. So, this adds a national dimension to the water wars in Colorado, which though they have been going on for more than a century, have in a sense just begun.

©1979 Marc Reisner

MARC REISNER is continuing his fellowship investigation into the Effects of the Federal Government’s Water Resources Policies on the Nation.