(First published Feb. 3, 1979 in the APF REPORTER)

Three-quarters of a century ago, the United States embarked upon a policy, the results of which would mock its own intentions. Because it has been an obscure policy–or, more accurately, a policy which dwells in that special kind of obscurity reserved for the very obvious–it has managed to continue virtually unchanged into the present day, despite an accumulating burden of poignant and bitter ironies. As one looks closely at the policy and its results, one begins to see striking parallels with our Vietnam experience. Those who were to benefit from the policy have become the losers. What was conceived as a reform measure ended up creating a powerful and corrupt order, which is largely dependent upon the United States government for survival. A landscape — or, at least, some of its most exquisite natural features –has been destroyed in order to “save” a region-at-large. What was supposed to be a great benefit to society has, in some respects, turned into an enormous liability. And there is no end in sight.

No easterner who has never traveled in the West can fully appreciate how arid the region is. West of the hundredth meridian –an imaginary line running roughly through the middle of the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma down to Laredo, Texas — the continent simply dries up.

In the East there is, or seems to be, a stream in every deeper valley, a brook or freshet in every wooded hollow; creeks appear on topographic maps like capillaries. In the West, one can drive for an entire day without crossing a trickle of water. For Wisconsin or New York or Mississippi to endure three weeks without rain is a drought; for much of the West to go for five months without rain is normal.

Precipitation is both seasonal and, due to continental weather patterns and the caprice of topography, geographically isolated. It rains considerably in the coastal regions of the Pacific Northwest and northern California, where the Pacific weather systems move inland. It rains and snows on the western slope of the Sierras, Cascades, and northern Rockies, which rise in the path of the continental fronts. It rains and snows in all the higher mountain regions, whose great updrafts create orographic precipitation. But in the western Dakotas and Kansas and Nebraska and Oklahoma and Texas; in the southern half of California and the eastern two-thirds of Montana; in the greater portion of Wyoming and Colorado and New Mexico and Arizona and Utah; in virtually all of Nevada; it hardly rains at all.

Water Would Follow the Plough

Few of the settlers who moved westward in the 1800s knew or believed any of this. Water, they thought, would “follow the plough.” God would reward their determination to civilize the wide continent.

They were ferried across the Mississippi and disappeared by the hundreds of thousands, into the mournful distances of the Great Plains, where a blazing and freezing wasteland awaited them. Those whose destination was California were more fortunate, for numerous rivers flowed out of the Sierra Nevada into the Central Valley, which was dry but exceptionally fertile, and the groundwater aquifers there were shallow and easily trapped. But much of the West, left as it was, was virtually uninhabitable. The rivers often flowed in steep canyons, and the settlers, staring into those bottomless chasms, were dumbstruck at the prospect of having to move the water onto arable land.

Riparian rights along farmable bottomlands were quickly seized, leaving the majority without a drop unless they were prepared to steal or fight (it is likely that as much blood was shed over water as was spilled over gold and women). Major John Wesley Powell, the legendary explorer of the region, told the Congress in the first official report on the and lands that a great federal reclamation effort would be necessary if the West was ever to be permanently settled; neither the settlers nor the states could do it by themselves.

Congress, however, was fearful of creating a pattern of federal paternalism in the West, and resisted the pressure for reclamation. It did try some backdoor approaches, notably the Desert Lands Act, which offered cheap acreage to anyone who could prove that he was irrigating it; and the Carey Act, which was designed to encourage state reclamation initiatives in reclamation programs. But neither was particularly successful at bringing irrigated acreage into production. The Desert Lands Act simply prompted thousands of speculators to buy and lands and hold onto them, intensifying the pressure on Congress to launch a federal reclamation program.

The Reclamation Act

Reclamation’s day arrived at the end of the nineteenth century. Major Powell, Senator Francis Newlands, and officials in the Department of Agriculture were lobbying vigorously for it (and supplying optimistic figures and cost estimates which later turned out to be grossly erroneous). President Theodore Roosevelt and the person who may have been his most influential advisor, Gifford Pinchot, were for it. The West clamored ceaselessly for it.

In 1902, the Congress finally acted, no doubt prompted by the fact that by then 90 percent of the private irrigation companies in the West were in or near bankruptcy. The federal government would assume complete responsibility for reclamation: it would build the dam and diversion projects, organize the distribution systems, manage the projects, and market hydroelectric power produced by the dams to help pay back the construction costs. Irrigators would be charged for the water they consumed, but the payback period would be long, and most important of all, there would be no interest costs. There were only two stipulations, both designed to drive away the speculators who had wheeled and sailed around the earlier settlement and homesteading laws like buzzards around hunks of carrion. First, no one receiving federal water could own more than 160 acres (if he did, he would have to dispose of the excess land at a pre-irrigation price); and second, he would have to live on or near the land he owned. Signing the act into law, President Theodore Roosevelt said, “The money is being spent to build up the little man of the West so that no big man from East or West can come in to get a monopoly on the water or land.”

The law was named the Reclamation Act of 1902, and the agency, which would carry out its work, became the United States Bureau of Reclamation. Together, they would transform the American West.

The Changes

The West, seen from the window of an airplane at 39,000 feet, doesn’t look much different today than it did a hundred years ago. It is still, for the most part, an uninhabited semi-desert, a harshly beautiful spectacle of mountains, mesas, and distant plateaus. Looking more carefully, however, one can see three obvious changes.

The first is that, in a few places, great numbers of people now live. One finds them in the immense urban concatenation that is Los Angeles-San Diego, a desert basin where some ten million have gone in search of a secular mecca. They live in the Bay Area, which, with its three-and-a-half million inhabitants, is perhaps thirty years behind Los Angeles. They live in the sprawling regional capitals of the Far West-Denver, Salt Lake, Phoenix, Albuquerque, Spokane, Seattle, and Portland-and in booming ex-towns like Billings and Boise and Rock Springs and Reno, spilling into the barrenness around them.

The second change is agriculture. Suddenly, in the middle of the palest desert, a vast garden materializes below. One sees it in the Central Valley of California, an Indiana-sized grid of angular green shapes; in the scorching and rainless Imperial Valley further south; on the eastern slopes of Colorado and Montana, where wheels of fortune-huge rotating sprinklers-have left irrigated circles on the landscape, as if some mile-high giant had walked through the region dropping coins. One sees it in the Snake River Valley in Idaho; in barren Arizona and New Mexico; in the arid reaches of eastern Washington and Oregon; in the Texas panhandle. The desert has bloomed.

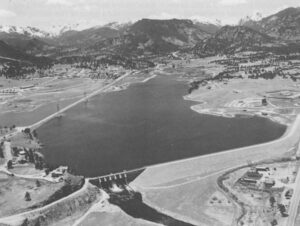

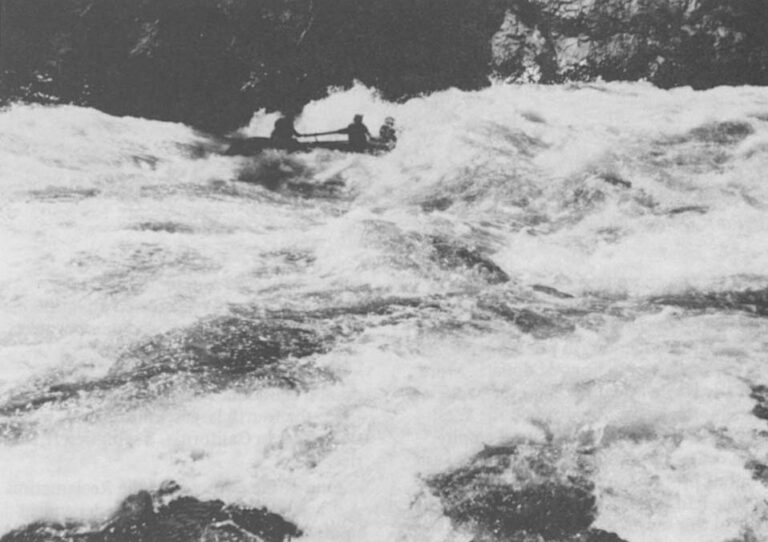

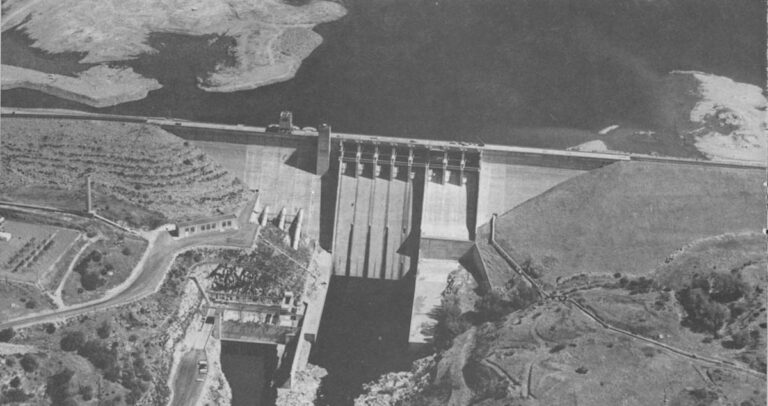

And then the third, and the most significant change: the dams. Except for intermittent free-flowing stretches, all the western rivers are now dammed. Flying a zigzag course over the West from Minneapolis to San Francisco, one sees the Missouri, the old riverine highway into the high country empire, now a series of giant reservoirs from the Rockies to the Iowa border. All the rivers one crosses over-the Green, the Platte, the Snake, the Flathead, the Arkansas, the Yellowstone-are dammed repeatedly. The lower Colorado, once the most tempestuous stretch of water on the continent, is now a series of endless canyon pools. And then, flying over the snow-piled Sierra summit toward the California coast, one sees the landscape of reservoirs on the western slope, dozens of pools backed up behind chinks of concrete wedged into the canyons and valleys. All the Sierra rivers – the Sacramento, the Feather, the Yuba, the Bear, the American, the Cosumnes, the Mokelumne, the Calaveras, the Stanislaus, the Tuolumne, the Merced, the Chowchilla, the San Joaquin, the Kings, the Kaweah, the Tule, the Kern-have been dammed once, twice, even a dozen times.

The Cost

The majority of the dams in the West — there are thousands in all — were built by states, municipalities, private enterprise, or the Army Corps of Engineers (whose mandate is primarily to control floods). However, most of the bigger dam projects, and those few which are so large that they have become legendary were constructed for irrigation by the Bureau of Reclamation, at a cost, in present-valued money, of tens of billions of dollars. More than any single thing that has ever happened there, they have transformed the West. They have made it both an agricultural empire and a center of population and wealth vastly out of proportion to what it might have become had there been no federal reclamation. In this sense, the Reclamation Act has served its purpose. In other ways, its purposes have been terribly distorted, and at times, upended.

Although the Reclamation Act was written expressly for the purpose of helping small farmers, western agriculture — particularly in the Central and Imperial Valleys of California –is dominated by large corporate farmers and landowners, many of whom receive water from the Bureau of Reclamation. For a variety of reasons, the explanation of which must come later, the bureau has violated the spirit, if not the letter, of its enabling legislation for over half a century.

The Awful Ironies

The Reclamation Act was never conceived as a federal handout to western farmers least of all giant agribusiness corporations — but the Bureau of Reclamation has turned western agriculture into one of the most heavily subsidized industries in the nation. By building projects whose extravagance can fairly be described as grotesque (some Bureau projects provide subsidies of over a million dollars per farm), the Bureau has created an insatiable demand for more water and more projects, and at the same time moved western agriculture outside the realm of rational market economics into a fantasy world. In 1972, the fourth largest consumer of irrigation water in California, a semi-desert, was rice.

One of the purposes of the Reclamation Act was to make the West less dependent upon the East for food and fiber. It has accomplished that purpose, and much more. Now it is the East that is dependent upon western agriculture, and the farmers in the East, not the settlers in the West, are the ones deserving pity. According to some estimates, nearly twenty million acres of agricultural land in the East has gone out of production as a direct result of reclamation in the West. While family farmers in the East struggle, and frequently fail, to survive, agriculture in the West has never seemed a better business.

The proponents of the Reclamation Act sold it to Congress as a conservation measure — conservation in those days meant, after Pinchot, the “wise use of a natural resource” — but today, with the definition of the word changed, the Bureau of Reclamation is hated by conservationists with a passion reserved not even for the likes of the Army Corps of Engineers. The toll of reclamation in free-flowing rivers stopped, mountain valleys inundated, wetlands drained, fish and wildlife eliminated, and desert canyons drowned has been incalculable.

The Reclamation Act was intended to promote the economic health and growth of the United States, but its implementation at the hands of the Bureau (together with the ordinary perversity of mass bureaucracy) has turned the Act into a burdensome economic liability. In the heyday of reclamation projects, in the 1950s and 1960s, millions of acres in the West were brought into production at federal expense, while millions of acres in the East were taken out of production, also at federal expense. The Central Valley project in California is now, according to an Interior Department report, heading toward an eight billion dollar deficit (the water user charge, which is fixed for forty years by the Bureau, will soon be unable to pay even the operating and maintenance costs of the project). Meanwhile, the salinity problems associated with irrigated agriculture – which were recognized eighty years ago but ignored, and which, according to some historians, have brought down more than a few civilizations in the past — are just now appearing. Solutions, if they exist at all, will be extremely expensive and, in all likelihood, federally subsidized.

How all of this has come about makes a long and extraordinary story. While it waits to be told, the Bureau of Reclamation, supported by influential western members of Congress, is planning and building dozens of new projects, and, despite the efforts of environmentalists, eastern farmers, and the President of the United States, it cannot be stopped.

©1979 Marc Reisner

Marc Reisner expects to write more about California’s water problems in our next issue.