Being an Account of a Brief Apprenticeship in an Obsolete Trade

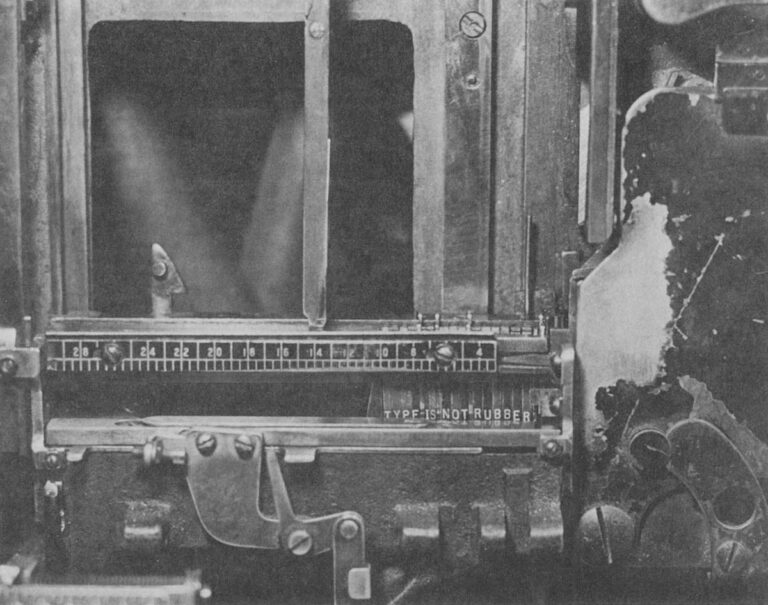

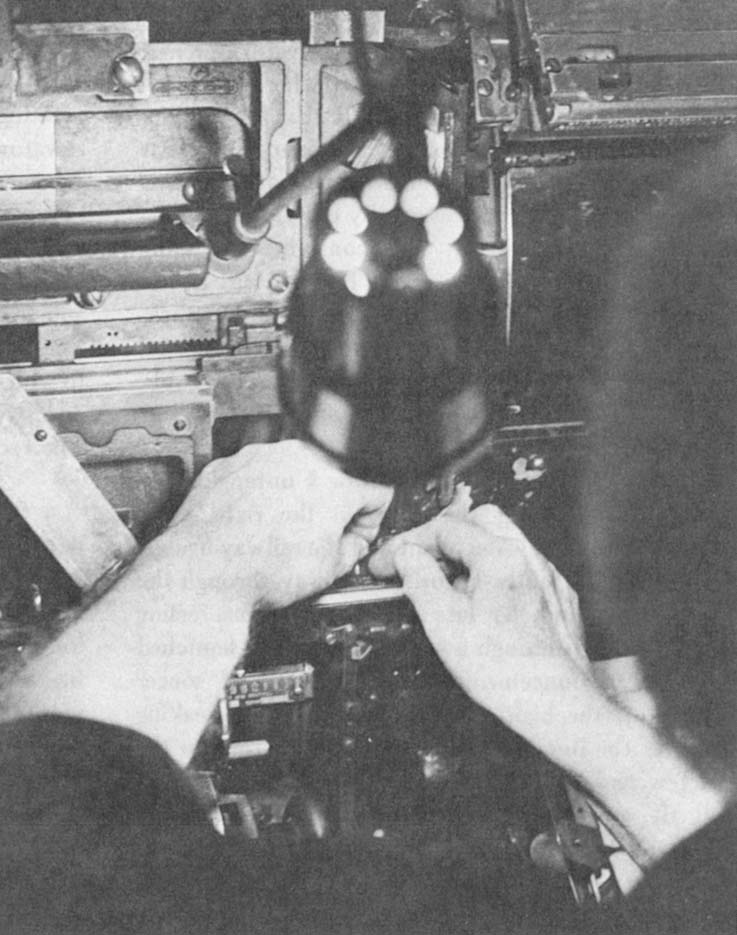

On the cover-A Linotype assembly elevator with the gate closed. This is the center of an operator’s attention as the mats tumble down and are arranged automatically in lines. The spacer bands adjust themselves to fill out the line but only so many letters can fit in any measure, proving the old trade adage that “type is not rubber.” Modern photocompositors have lenses that can distort the image of the letters to fit where they couldn’t .Today, type is rubber.

“The linotype is a machine that depends entirely on its operator. It is not like an indifferent robot, that needs but an electronic impulse to propel it. On the contrary, it is a highly specialized apparatus that obeys only to the one that treats it properly. One might be tempted to compare the linotype with a wellbred race horse, responding to even the slightest move performed by its master.” from Ottmar Mergenthaler and the Printing Revolution by Willi Mengel translated (somewhat clumsily from the German) and published in 1954 by the Mergenthaler Linotype Company of Brooklyn, New York to mark the centenary of Mergenthaler’s birth.

Friends and newsletter readers who know something of my obsessive interest in these matters were not surprised when I announced that I was going to Ohio to learn how to operate a linotype machine. Of course, some of them merely understood that I am fascinated by old printing machines the way hobbyists collect butterflies and others seek out steam locomotives in remote parts of the world. But there is more method to my madness for the linotype is the very sign of the first American Industrial Revolution, a machine that Thomas Edison declared in all sincerity, was the eighth wonder of the world.

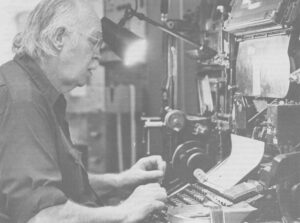

This is a terrible time to take up linotyping. Obsolete high school shops still teach it but linotyping is not a skill in fresh demand. The world, at least the American part of the world, is filled with more linotypists than it needs. There isn’t even time to take proper linotype lessons. When he was a boy at the Yellow Springs News, Carl Champney practiced on a dead keyboard for two years before his father switched on the power and let him try his skills on the living machine. Carl thought it would be an all-purpose skill, a way to earn his keep no matter where he wandered. Now even in his father’s shop, his linotype skills will soon be in small demand. Carl prefers to work in the office of the Yellow Springs News anyway.

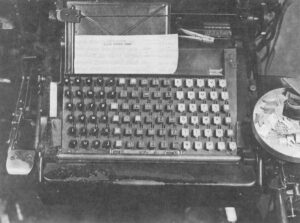

My first and only formal linotype lesson was very brief. Ken Champney turned on the Comet Linotype and, while I watched over his shoulder, he showed the keyboard, the assembly elevator and tile casting lever. “Lift it gently. Some people try to put it through the roof,” he said. Then he set a few demonstration lines. End of lesson. Ken handed me a legal notice, adjusted the mold to cast 6 point type and left me to begin my career as a novice operator.

The novice operator was soon at sea. The legal notice concerned the Common Pleas Court of Montgomery County sitting as the Conservancy Court of the Miami Conservancy District. It dragged on line after line in describing a section of river bank that was to be condemned for a park. The notice was chocka-block with legal phrases concerning “lands on the west side of the Cincinnati-Dayton Road between the south West Carrolton corporation line and Miami levee” and “located within 450 feet of the river channel from the north end of Miamisburg to the railroad bridge south of Miamisburg, the recreation area south of the Miamisburg Wastewater Treatment plant south to Montgomery County line” and so on and on and on. The text wound back on itself, repeating these legalisms until I lost my place and ran one 450 foot line into the next 450 line, leaving out the railroad bridge. Soon I was gingerly holding the hot slugs under the light, straining to read 6 point type. What had I done with the wastewater treatment plant? Keeping my place was complicated by my fear that a wrong move would cause the machine to explode. That or Jam beyond recall. Or maybe both. I was acutely aware of the pot of molten lead just beyond my left hand.

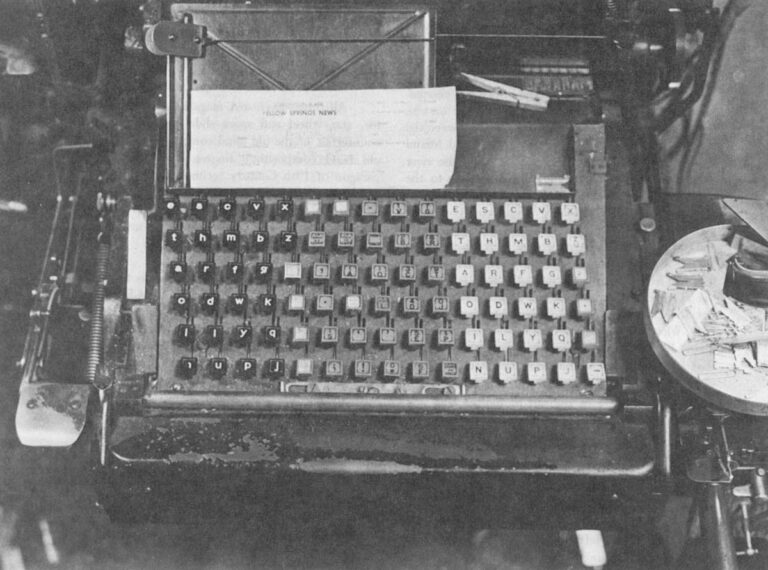

You must understand that a linotype is essentially three machines working in complex alliance. The power keyboard is quick and a heavy touch brings down double letters on the ham-handed novice. It is actually three keyboards side by side-lower case to the left, upper case to the far right with “figs” and punctuation in the middle. Unlike the standard Remington typewriter keyboard, the linotype’s is vertical with most of the vowels in the left hand column. The left hand is supposed to work with a rocking motion of thumb and index finger. The right hand works the other columns in each section. Spacing bands are brought down by the heel of the left hand hitting a steel lever that has been polished by the millions of times it has been struck.

Directly above your head are the aluminum magazines that hold the brass matrices from which the slugs are cast. Each keystroke opens a channel at the bottom of the magazine and gravity carries the mat down a chute into the assembly elevator. At eye level is an indicator slide that shows how much space you have left in the line. The assembly elevator is to the left of the slide. Here the matrices and space bands come together. A gate at the front of the elevator opens so you can reach in with your fingers to correct mistakes or handspike the line.

At the right side of the elevator is the constantly spinning star wheel, three leather flippers that keep the matrices from falling over. The star wheel bites the fingers of novice operators who try to push in more than the measure will allow.

All these-keyboard, magazines, assembly elevator, star wheel and space slide-are ‘Mergenthaler’s counterfeit of the old hand composing stick and the old hand compositor’s fingers. The Linotype, this paragon of 19th Century technology, displaced tens of thousands of craftsmen who set type by hand. Now in its technological twilight, the Linotype was the breaker of a much older profession and the ruin of many a hand compositor’s fortune.

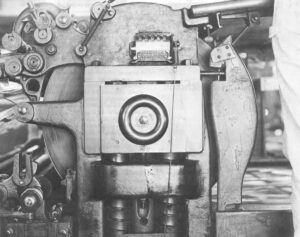

The second part of the linotype is the casting apparatus directly to your left. Once the line is composed, the operator grabs the fat stock of the casting lever and presses down. If all goes well, the assembly elevator carrying the mats and spaces goes straight up where a shuttle snatches it out of the mechanical stick and carries it to the mold. The casting proceeds without human intervention while the operator is supposed to be hard at work on the next line. But the novice usually watches in awe as the mold closes, the pot pumps a shot of molten lead against the face of the mats, a second elevator lowers an arm down to grab the mats, the slug is ejected, sawn smooth and slid into the galley rack.

The slug is still very hot and while veteran operators think nothing of picking it up between their callused fingertips, the novice is in for a nasty initiation the first time he attempts the trick. The process is not called hot type without reason. A time honored prank of wizened linotypists is to hand a freshly cast slug to an apprentice or better yet a nosy neophyte from the editorial department. As the victim reaches out for the slug, the linotypist drops it into the tender palm and the reflexive closing of the hand doubles the pain. The trick only works once.

The third section of the linotype is the sorter. One of Mergenthaler’s inspirations was to circulate the same set of matrices automatically and thus dispense with the time consuming business of distributing type back to the cases. The lead type slugs are melted down after use and the automatic distributor allows the machine to cast an unlimited amount of type from a limited number of matrices. The spacing bands drop out of the released line and are carried back to their original position by a slide. The matrices are picked up by a second elevator arm and lifted to the top of the machine where they are pushed onto a pyramid-shaped track that has notches cut into the sides. The notches are arranged so that they end over the open channels of the mat magazine. A clicker sends the matrices one by one running along the track, propelled by two constantly spiraling matrix return rods. Each matrix has a V cut at the top to correspond to the notches in the carrier track. When the notches run out, the mat drops off and falls down into the channel of the magazine, ready again for another circuit through the machine.

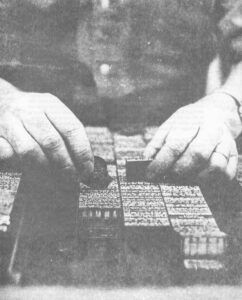

That is the theory. Somehow I untangled my legal notice, getting the river in the right place between the wastewater plant and the railway bridge. Slowly but diligently I worked my way through the whole thing and, by late afternoon, I was feeling cocky. I raced through a society notice and launched into an announcement of the opening of soccer practice at the high school. The lines were breaking well. As the line fills, the operator gets down to the last few lines and must decide if another whole word will fit or if he should hyphenate the word and carry the tail over to the next line. This is the chief skill of a good operator-to set tight lines that don’t end in orthographic deformity. To do it right, your attention is divided between the copy, the spacing, slide and the assembly elevator. The mats have their characters printed on the outer edge so that you can read the line as the mats drop into place. To fix a mistake or rearrange the spacing you can open the gate and reach in with your fingers. The soccer story, was going well until I ran into a patch of names which either had to be chopped in unnatural places or spread out by acres of white space. Distracted by the copy, I sent up a line with the gate open. The elevator jammed. Using the screwdriver that is always parked on the caster, I gingerly pried back the slide. The mats and slides rained down the front of the machine and onto the floor. For the next half hour, I hunted around amidst the lead splashes and shavings to find them. Then I compounded the mistake by sending the wreckage of the line back up with some of the punctuation matrices in backwards, creating an unholy tangle in the distributor on top. Then I had to climb up on the back rail, open the top of the distributor and work the mats off the track to get at the offenders. At one, point, I had 40 or so mats spread out on the top of the machine, in both hands and across a convenient table top. Night found the novice operator greatly chastened with the soccer story still undone.

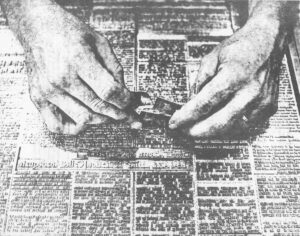

Next day things went from difficult to exasperating to painful. I set new records in jamming the elevator, in mixing magazines and dropping mats. Around noon, I sent up a line that for reasons unknown slipped out of the elevator at the top of its lift. The brass matrices came cascading down, pinging off the cast iron, jumping into nooks and crannies and scattering in all directions on the concrete floor. The other linotypists froze as the last few mats jingled to rest. Lynton looked up from the next machine and stroking his Jaw opined. “It sure sounds funny when somebody else does that.”

The situation worsened. After collecting the wreckage from the floor, I circled the machine, screwdriver in hand, winkling out mats that had taken refuge in the innards. Thus I came upon a cache of long lost mats on a ledge behind the keyboard. Feeling extremely proud of myself, I set them up without realizing that many of the fugitives were from another magazine. I had committed one of the cardinal sins of linotyping-mixing mats from other magazines and overfilling the channels with too many mats. Further, some of the refugee mats were bent. The jam was of colossal scale. Lynton patiently showed me the little serial numbers on the sides of each mat that identified the magazine it belonged to. There was nothing for it but to empty out each channel completely and sort out all the mats. I had domino rows of brass on every available surface. Once the sorting was done, I sent up a line and then climbed up behind again to pull out the extras and the bent ones from the distributor. Late in the day, the machine was running tolerably well but I had to hand over my copy to Dot so that she could finish the story. Time and deadlines wait for no operator.

Setting type gives you a different perspective on words. It’s not their meanings that make words different, it’s how fat or skinny they are and whether they can be broken at the end of the line. Fat clumsy words become extra passengers in a boat, throwing their weight where it is least needed and threatening aesthetic upsets. Little words are best, full of “1”s and i’s” You can pack them like sardines. When a word must be long, let it end in “ing” which can always be neatly carried over to the next line.

A paragraph can turn ugly on you without notice. One moment, those prefixes and suffixes are falling beautifully into place, the next, the word “gargle” is snarling at you. Can you break “gargle” after “gar?” Is there room after “death?” When things are going poorly, you read sinister meanings into the simplest sentences. Or outrageous double entendres. A softball story says, “The Robinettes go head-to-head Tuesday with the Progressive Printers, the team that now ties them for the top spot in the women’s ‘Red (upper) league.’ “What exactly goes, on in the “Red (upper) league?”

As the days wore on, my speed did not improve but at least I became adept at the standard remedies for the standard mistakes. I still sent up the occasional line with the gate open but I could judge when it could be saved by careful prying and when dumping the line was the better part of valor. Clearing the assembler and the distributor were tricky but I grew confident that with enough fiddling, I could get the machine going again. I drew the line at problems inside the caster. Horror stories of lead squirts and a good look at the precisely machined interior surfaces of the mold disk wisely convinced me to call for help if the caster balked. A Linotype teaches respect.

The News has six Mergenthaler Linotypes, the oldest, the Model 5, sits near the window with its original keyboard replaced by a standard electric keyboard-a short-lived experiment in having non-linotypists run a Linotype. Next in seniority is the old reliable Model 14. Then come the technological refugees, the machines the News picked up dirt cheap as other papers cast them off. They acquired nicknames after their origins- “Clyde” being from Clyde, Ohio, “Waverly” from Waverly, Ohio and “Bucky” from Dubuque, Iowa. “Slick” came from Oil City, Pennsylvania. A reporter suggested the name of “Gusher” but the linotypists, ever fearful of lead squirts, wouldn’t give any machine so unlucky a name. But what about the old ones? Does the Model 5 have a name? Ken laughed at the notion. “The Model 5 was here before any of us.”

A Linotype teaches respect. Despite all the foolish mistakes the novice operator may commit or maybe because of them, the machine has dozens of clever safeguards- levers that keep the mold from casting if the line isn’t right and springs that take the strain off key parts when something goes wrong. The Linotype manual from the Mergenthaler Company waxes rhapsodic over the failsafes built into the system. Hovering over the operator’s head is the, spirit Of Ottmar Mergenthaler. Dead 77 years, his mind lives on in the shape of cams and in the arrangement of gears. Says Ken, “You can’t run a Linotype without developing a tremendous respect for the guys who invented it.” When Lynton was discussing some of the troublesome features of the two “new” Model 32s, that have side magazines and special adapters to set larger sizes of type, he brushed off these postwar gimmicks, “That couldn’t be one of Otto’s. Otto would never have done it that way.”

The way Otto did it, everything was adjustable or replaceable. “That Model 5, it’s one of the early machines. It’s like the Model-T, you can always fix them.” And they don’t wear out, says Lynton. “Look at the cam roller (under the typeboard), it has an eighth of an inch groove worn it. You can imagine how many millions of times that thing has gone around. it’s like going to Philadelphia and seeing a stone step worn down from use.”

Young or old, a Linotype is temperamental. “it works well when it works well. Little things are always going wrong. Any of them can give you trouble.” It takes a good operator to keep one going.

Another morning I battled through a long letter about energy, a topic much on the minds of Ohioans. I even figured how to set the signature flush right in boldface. Having filled half a galley with type, I fetched a tray to clear it off and slipped a precut 16 pica lead at the foot of the type to mark the end of the letter. The lead was wider than the type. I measured the type. The slugs were 15 picas. My half-morning’s work went into the hellbox and I started over.

By noon, I had recouped my losses and pulled a proof. As I set my corrections, it all seemed to come together. Line after line went up, cast and redistributed without hang-up. when I jammed the assembly elevator, I fiddled with some aplomb (and the screwdriver) and managed to save the line. I thought I glimpsed the art of operating. The key seems to be in holding a steady rhythm. Steady as she goes. Dink, dink, dink on the keys. Lever up. Ka-chunk, the line goes over. Thunk. She casts. The second elevator carries away the mats. Click, click, click. The mats are counted off. Concentrating on the keyboard, I nearly Jumped out of my seat when the falling matrices came roaring down the channels of the magazines, catching me unawares.

Spacer bands remind me of fish. They are a stainless steel double wedge with the rivet at the bottom resembling a fish eye and the arms on the upper slide the fins. Looking at the spacer from the side. you can see the taper from head to tail.

Later in the week, a new wrinkle was introduced. Each mat has two letter forms incised on its face, one in the Roman face and the second either in boldface or italic. To get the second face, you throw a lever on the left of the keyboard that raises a second rail inside the assembly elevator and makes the mat you want to cast boldface sit up higher.

I was setting a question and answer interview. The names at the start of each entry were italic, requiring the lever forward, then the answer had to be set normally with the lever back. The space mats to indent the start of a paragraph had to be set in the normal position or they would cast as hyphens. To get italic and boldface in the same line requires the heretical mixing of mats from two magazines, a procedure both time-consuming and fraught with complications. Lynton has always held it to be the height of editorial folly. “It’s damn nonsense to use both boldface and italic,” he declares.

But even without that twist, I found myself tortured on the rack of setting italic. I kept forgetting to throw the lever forward and then had to open the gate and lift the mats onto the second rail by hand. My clumsy fingers either knocked the others loose or they were caught by the stinging slap of the star wheel. The proof revealed that my spaces were up when they should be down. Late in the afternoon Lynton looked across to see why I was moaning and cursing. “This damn italic,” I cried. He nodded sympathetically. “Nobody considers the poor linotypist.”

The text was set on an IBM Composer and the headlines on a Varityper by Mrs. Hazel Richmond at the UCLA Department of Journalism, Los Angeles.

Photographs and layout by John Fleischman.

Proofread by Louis Watanabe.

Received in New York March 1978

TO BE CONTINUED

©1977 John W. Fleischman

John W. Fleischman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Human Behavior Magazine. His fellowship subject is “The Medium of Print: A Craft Becomes a Computer Function.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Fleischman as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to Human Behavior Magazine. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.