Indications and Intimations

All photographs courtesy of the Los Angeles Times.

The editor who has teenage children but who doesn’t like to think of himself as a relic of a bygone era had noticed the work going on in the Composing Room. He had even heard of the plans for a hot lead exhibit. But when he actually looked through the glass partition to see a linotype machine set up with all its associated paraphernalia under a sign proclaiming, “Los Angeles Times, A Corner of the Composing Room, 1881-1974,” a feeling of horror came over him. Here, under glass, in a museum, was the workday world he had inhabited nearly all his adult life. Three years ago, linotypes were as common as pencils right where he was standing and now they had one under glass. He moved on, contemplating a dark paranoid theory that this was some enigmatic corporate message, that perhaps next week he might come back to see a stuffed reporter set up next to the linotype. It was a feeling not unlike being buried alive.

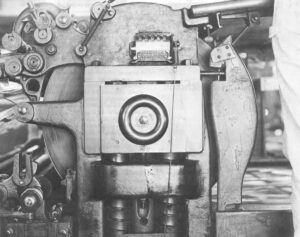

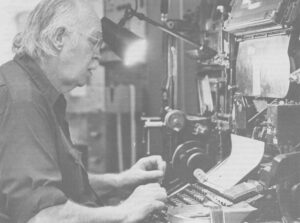

Will Davidson unlocked the door, flipped on the light and stepped back into the long lost era of 1974, when compositors were men and lead was hot. The linotype exhibit room was Davidson’s baby. During the years when the great metal Composing Room was being dismantled and room cleared for the new electronic equipment, Davidson was busy squirreling away bits and pieces of machinery. Once the dust had settled, Davidson who is the Superintendent of the Composing Room secured this room fronting on the central corridor and began rebuilding a working hot lead shop. The original wooden block floor was uncovered. The Times machine shop overhauled the machinery including a complete disassembly and refit of Mergenthaler No. 61296, a Model 31 the Times paid S8,478.81 for in 1949, the year Davidson Joined the paper. Today, No. 61296 is in mint condition, the brass magazines gleaming, its Mergenthaler nameplate repainted in blue with the letters picked out in silver.

Will Davidson unlocked the door, flipped on the light and stepped back into the long lost era of 1974, when compositors were men and lead was hot. The linotype exhibit room was Davidson’s baby. During the years when the great metal Composing Room was being dismantled and room cleared for the new electronic equipment, Davidson was busy squirreling away bits and pieces of machinery. Once the dust had settled, Davidson who is the Superintendent of the Composing Room secured this room fronting on the central corridor and began rebuilding a working hot lead shop. The original wooden block floor was uncovered. The Times machine shop overhauled the machinery including a complete disassembly and refit of Mergenthaler No. 61296, a Model 31 the Times paid S8,478.81 for in 1949, the year Davidson Joined the paper. Today, No. 61296 is in mint condition, the brass magazines gleaming, its Mergenthaler nameplate repainted in blue with the letters picked out in silver.

Besides the linotype, Davidson has a Thompson caster for display faces, a table saw for cutting, leads, two typecases, a make-up dump, a galley press, a denim apron and a green eye shade. It’s a first class shop which, according to Davidson, is the way it has always been at the Times. “Everything about it was great-the people, the employer, the tools. Everything was first rate.” It was a welcome change after the job shop Davidson had been working in. At the Times if you needed a four inch rule, you threw the other foot of it into the hell box. Spacing leads were only used once instead of being dug, greasy and inky, out of the chase for the next job. “We’d melt everything down. It was such a luxury after working in a small shop,” he says.

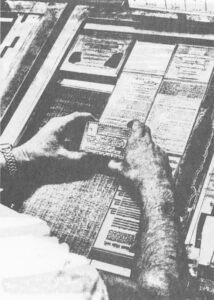

Davidson has also filled a display case with some of the hand tools peculiar to the trade-composing sticks, type high gauges, ink brayers, wooden mallets, planers and makeup rules. A make-up rule is a steel rectangle about the size of a business card. In the hands of an expert, the make-up rule could pop loose the most tightly jammed slugs, slip lengthy corrections effortlessly into place and bring order to the most slopped up form. Over the years, a rule would wear to the owner’s hand. Many printers, Davidson included, still carry theirs as keepsakes. He reaches into the display for an angle gauge, one of a home grown variety that the Times machine shop used to manufacture. It is a steel V joined at the base by a pin, used to measure angled lines. Say you had a furniture ad. The advertiser wanted the words, “Last Four Days” in big black letters slanting uphill across the page. You measured the angle from the paper dummy, says Davidson, and then you carried the gauge over to the saw to slice up a lead block into wedges that held the slanted line in place. “It was like a puzzle.”

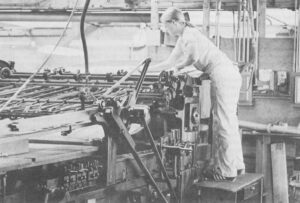

Certain advertisers believed that the more type they got into their space, the more they got for their money. “They’d have lots of angles in them with as much type as they could squeeze in.” He steps over to the saw and demonstrates how the angle gauge worked. “In paste-up, you can do so much more. These angle pieces, you can just paste them down. It could take us a half hour to make angles.” Davidson remembers the big two-page department store ads. “You start in on a double truck ad and you’d never get done with it in a shift.”

Certain advertisers believed that the more type they got into their space, the more they got for their money. “They’d have lots of angles in them with as much type as they could squeeze in.” He steps over to the saw and demonstrates how the angle gauge worked. “In paste-up, you can do so much more. These angle pieces, you can just paste them down. It could take us a half hour to make angles.” Davidson remembers the big two-page department store ads. “You start in on a double truck ad and you’d never get done with it in a shift.”

The work today is easier, faster and cleaner, says Davidson, but it’s just not the same. Little things that were habits and rituals are hard to forget which is part of the reason he set up the exhibit. Take the case of “Etaoin Shrdlu” who was not a Frenchman of Rumanian ancestry but the way a good linotypist cleared the odd matrices that accumulated over a shift before going to lunch. Davidson turns on the Model 31 and sets a few lines. Odd sorts and mistakes are pulled out by hand and set aside. After a few hours, you would cast them just to get them off the machine, he says. The last line would usually come up short so to fill out the line you would run your fingers down the first two rows of the keyboard–etaoin shrdlu. Davidson picks up the hot slug in the time honored grip between thumb and index finger. “It’s nostalgic as heck,” he confesses.

The LA Times isn’t the only newspaper to have a linotype museum. The Lafayette (Indiana) Journal and Courier has one. Linotypes are also in vogue as an interior decorating touch at some papers. The San Jose Mercury-News has one set up in the lobby, nestled amid the potted palms. And a linotype will usually draw a tour group’s attention, say public relations types, the way a VDT will not.

Coming back from lunch, Jim Robertson stopped with his visitor to admire Davidson’s exhibit. In 1969, Robertson had a brand new BS in physics from the University of Texas at Austin and a job offer from RCA to go out to Los Angeles to join their new Graphics Division. “At the time,” he recalled, “I knew nothing about graphics.” Now eight years later, the systems analyst was standing before this trophy of the technological wars. “That is an incredible machine. I remember the first time I ever really looked closely at one of those machines. It was just after I came to RCA. It’s just an incredible machine.”

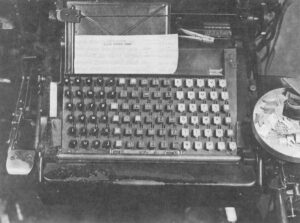

As a onetime brash outsider, Robertson professes a respect for the skills of the metal craftsmen. He joined the Times in 1971 and helped develop an extremely sophisticated terminal that makes up display ads on a screen with the use of a sonic pencil. Using the pencil, the operator specifies typefaces and sizes by pointing to a type “menu” and then marks their position on the screen. The terminal logs the coordinates of each touch of the pencil so that the operator is no longer pasting up tiny scraps of paper type. The job requires nothing like the manual dexterity of the old metal ad row that was once the preserve of men like Will Davidson. Yet Robinson says that the make-up artists, many of whom worked the old ad row, have developed methods on the terminals that astound him. “I watch the people who do our display ads and a lot of the skilled things they used to do, they still do. I designed the display system but I couldn’t do the things they do with it.” Every so often, Robertson is taken aside by a make-up artist with the prefatory, “Did you know it could do this?” Robertson is then shown some variation or added convenience that was certainly not envisioned when the system was set up. “They’re not afraid of it. People have taken it over without seeming to resent it.”

During his first few years at the Times, Robertson worked almost exclusively with the Production Department. With the coming of the NES, editors have taken an interest in the activities of Robertson and his colleagues in Information Systems. “The people who were using the older systems were production people. They were hired to run the machines. But their Job wasn’t to report the news.”

The electronic newsroom will return the total responsibility for the news to the editors and writers while giving them the means to cope with it. The Production Department will not disappear, Robinson believes. They will be turning ads into type for the foreseeable future. But the NES will get Production out of the news business. “It’s a matter of the news people doing everything they’ve done before and everything that has been done for them by the Production Department.”

Turning editors into editor-typesetters is not a simple task even through the agency of a giant computer and its attendant hardware. The bottom line in printing is laying down type. If there is one thing Herb Mann knows, it is how to lay down type which is something that the new editor-typesetters can’t be expected to understand. Since editors will be doing just that in the future and printers like Mann will not, it is up to Mann to write formats so the computer will make up the difference. So Herb Mann spends his days in the Editorial R&D Room, trying to pass on a lifetime in the trade to a computer.

Mann is very insistent about his field of expertise. “I’m not a programmer. That’s the first thing you should know about me. I’m a printer. I know how to set type and essentially that’s all I know. Along the road in helping to develop all these typesetting methods, I’ve worked with programmers. I can talk with them so that they can understand what I’m saying and I can understand what they are saying to me.” Turned into programs by an outside software contractor, Mann’s formats will be setting the Times long after he retires this coming November. It is a curious kind of immortality.

It is not how Herb Mann thought he would be spending the last years of a 44-year career as a printer. His hands are clean. A typesetting machine hasn’t spat molten lead at him in years. At times, it can be disorienting. Mann will go walking through what is left of the composing room, past the rows of terminals and special typewriters and, for a second, he will see it all as alien. “I still haven’t gotten used to it. It’s just not like a newspaper to me. I’m so used to hearing the clank of linotypes. It’s something I’ll never get used to.”

It is not how Herb Mann thought he would be spending the last years of a 44-year career as a printer. His hands are clean. A typesetting machine hasn’t spat molten lead at him in years. At times, it can be disorienting. Mann will go walking through what is left of the composing room, past the rows of terminals and special typewriters and, for a second, he will see it all as alien. “I still haven’t gotten used to it. It’s just not like a newspaper to me. I’m so used to hearing the clank of linotypes. It’s something I’ll never get used to.”

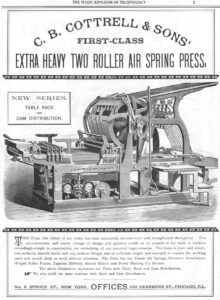

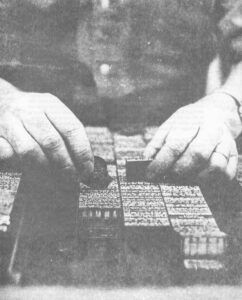

What is missing is the distinctive sound of brass matrices falling through the metal channels of a linotype. The sound was in the air when Herb Mann first walked into the shop of a small newspaper out in the Imperial Valley of California. It was 1933 and although Mann had ambitions to study engineering, the offer of a job sweeping out the shop of one of El Centro’s two newspapers was, after all, a job. Being bright, curious and standing right there, Mann was set to work setting headlines on a curious hybrid machine called a Ludlow Typograph. The Ludlow combined the traditional skill of hand setting by which everything had been composed from 1450 when Gutenberg invented the technique with the hot lead linecasting process that was the heart of Otto Mergenthaler’s linotype. Instead of type, the Ludlow had separate brass matrices which Mann assembled on a specially slotted composing stick and then locked onto the machine for casting into a slug of lead. Then Mann unlocked the stick and redistributed the matrices to the job case before moving onto the next line.

Mann was soon moved from the Ludlow to the make-up stones where all the type, headlines and engravings were assembled into a solid mass inside a steel frame called a chase. Long leads were slipped in between the columns to hold them tight and the page was then locked with wedges to stand the final test. A corner of the chase was lifted from the stone and the make-up man drummed on the type with his fingers to see if any of the hundreds of pieces of metal would drop loose. Getting a page to lock on first try requires considerable skill and some luck. The luck diminishes for a good make-up man and the skill increases. Mann became a highly skilled make-up man and was quickly moved to ad row where the vagaries of advertising typography can try the true measure of craftsman’s ingenuity.

As an apprentice, Mann was fair game for the ancient initiation rites of the shop such as “type lice.” The novice is called over by a veteran to see these curious vermin. The veteran has set a block of loose type down in a pool of half dissolved ink and the victim is told to took closer. As he bends over, the veteran squeezes the type together and the liquid shoots up through the cracks into the victim’s face. Gutenberg probably pulled it on Peter Schoeffer in 1455.

Once Mann was sent out in search of a “type stretcher.” There being two newspapers in El Centro at the time, the foreman had some scope for a wild goose chase. The other foreman solemnly raised a great search for the type stretcher before sending Mann back empty-handed. Mann shakes his head at the memory. “I came back and all the old hands gave me a hard time. And the boss said, ‘I know they got one. They borrowed ours so they’ve got two.’ And he made me go back.”

Mann survived and gradually picked up all the skills of the backshop. When a wiseacre linotypist taunted him about not having the brains to tackle a real man’s job, Mann took a linotype lesson from the foreman and then came in on Sundays for six weeks to practice. Within four years, Mann became foreman himself. By 1943, he felt he had climbed as high as he could go in El Centro and drove into Los Angeles one day to get hired on at Times-Mirror. “Down in the valley, I was an ad man so they put me on make-up which I had done the least of. It’s like the Army.”

Mann survived and gradually picked up all the skills of the backshop. When a wiseacre linotypist taunted him about not having the brains to tackle a real man’s job, Mann took a linotype lesson from the foreman and then came in on Sundays for six weeks to practice. Within four years, Mann became foreman himself. By 1943, he felt he had climbed as high as he could go in El Centro and drove into Los Angeles one day to get hired on at Times-Mirror. “Down in the valley, I was an ad man so they put me on make-up which I had done the least of. It’s like the Army.”

Mann prospered on the Chandler papers. He was made assistant make-up foreman on the Mirror in 1948, and then assistant linotype foreman on the Times when the Mirror folded in 1962. (The Mirror and the Times shared the same linotype and ad row but maintained separate make-up areas where the pages were assembled. Composing Room employees shifted back and forth, even within the same shift, if the work demanded it.) In 1965, Mann was made a foreman of the Composing Room.

Automation did not arrive at the Times overnight. Taking advantage of its nonunion shop, the Times was one of the first papers in the country to bring in TTS (teletypesetter) paper punch machines. The goal was to automate the hot lead process completely and Mann was involved from the beginning. To Mann, it was a challenge but to many of the old-timers, it was merely threatening. “I remember one fellow in particular who used to set the horse race charts. This one fellow used to say to me, ‘Now you’re trying to figure out a way to set the horse race charts. What’s going to happen to me when you get that figured out?’ And I told him, ‘Carl,’ I said, ‘I think before I get that one figured out, I bet you’ll be retired.’ And that’s the way it turned out. He retired about two years before We were ready to do that. By the time we got around to do it. we weren’t on hot type anymore. We were in photo composition.” Mann admits that the sudden switch in signals from automated hot lead to photo composition caught him flat-footed. “I was one of those that didn’t think it was going to come that fast,” he recalls. “The world was passing me by.”

(The Times has a company policy that no permanent employee will lose his or her job as a result of automation. However, the Times virtually stopped hiring full-time Composing Room employees in the early ‘60s .The remaining linotypists shifted to proofreading assignments after the cold type conversion in 1974 were men with 22 and up years of seniority. However, many “part-time” linotypists who had been working for as long as eight years were let go. The largely female pool of typists brought in to run the tape punches and then the optical scanner typewriters were hired as temporary employees with the clear understanding that eventually they would be laid off.)

Then in 1973. his wife had a stroke and for a while, it looked as if Mann would retire early to care for her. Gradually Mrs. Mann’s condition improved so that he could work through to 65 and claim his full benefits. He was assigned to the Will Locke and the Editorial R&D Room. At first, Mann held onto his Composing Room desk until he realized that he was in Editorial for keeps. Thus Herb Mann became the first of what Locke believes will be a new kind of editorial technician with strong typographic skills and a head for production problems. Mann isn’t sure what title his successors will carry but he is positive that while “printers” may disappear from the Times, “There will be people around that will in some way or somehow know a lot of what I know today. There’s going to have to be. You’re always going to be laying down type in one form or another. You’re going to be setting type no matter how you do it. And you’ve got to do it esthetically and you’ve got to know the language although the language may change. It probably will with the metric system.”

Then in 1973. his wife had a stroke and for a while, it looked as if Mann would retire early to care for her. Gradually Mrs. Mann’s condition improved so that he could work through to 65 and claim his full benefits. He was assigned to the Will Locke and the Editorial R&D Room. At first, Mann held onto his Composing Room desk until he realized that he was in Editorial for keeps. Thus Herb Mann became the first of what Locke believes will be a new kind of editorial technician with strong typographic skills and a head for production problems. Mann isn’t sure what title his successors will carry but he is positive that while “printers” may disappear from the Times, “There will be people around that will in some way or somehow know a lot of what I know today. There’s going to have to be. You’re always going to be laying down type in one form or another. You’re going to be setting type no matter how you do it. And you’ve got to do it esthetically and you’ve got to know the language although the language may change. It probably will with the metric system.”

Metric conversions and front end systems are a long way from the pica sticks and Ludlows in El Centro where Mann walked into his trade. What does he tell youngsters today who are interested in printing? Mann says he would recommend mathematics as a good foundation and a touch of computer programming couldn’t hurt. He thinks electronics installation and repair require some of the manual skill that metal printing used. But what advice would he give a novice printer? “This is interesting because I had it happen to me. A few years back when I was linotype foreman and they were just getting into paste-up and I thought, ‘Well, I used to be a make-up man, it would be interesting if I took a course in paste-up.’ So I signed up for a course in paste-up over in Woodland Hills and they had some linotypes over there. These guys who were signed up for the linotype course found out I was the linotype foreman at the LA Times and right away, they started cosying up to me, figuring that if they learned linotype, I could get them a job. And I told them, ‘What are you taking up linotype for? This is going to be as extinct as the dodo bird. Take paste-up.’ That’s what I told them ‘cause at that time I couldn’t foresee we were going to get into pagination and that paste-up was going to be going out.”

“So you ask what should I say today?” Mann pauses for a moment and then answers in a quiet voice, “I really don’t know.”

The text was set on an IBM Selectric Composer in Bodoni Medium by Mrs. Hazel Richmond at the Department of Journalism, University of California at Los Angeles.

Received in New York on July 25, 1977

©1977 John W. Fleischman

John W. Fleischman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Human Behavior Magazine. His fellowship subject is “The Medium of Print: A Craft Becomes a Computer Function.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Fleischman as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to Human Behavior Magazine. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.