Yellow Springs is not your average country village and the Yellow Springs News is not your average country weekly. There are about 5,000 people in Yellow Springs but no one seems in any hurry to proclaim the place a town. The people of Yellow Springs feel they have something special in their village. They want to keep if that way. Growth is an unpopular word in village politics and the hottest battles rage over zoning changes and building permits. The sprawling tracts of Dayton and Fairborn are marching over the pastures and corn fields to the west but the village has an ambitious greenbelt program to halt the advance. It is a college town that draws a lot of its bohemian flavor and its high technology economic base from the generations of Antioch students who came to study and remained for the small town atmosphere.

The main drag is Xenia Avenue. It’s got one hardware store, one supermarket, one bank, one undertaker, two gas stations, and one variety store. There are also a few other outlets of traditional midwestern commerce, the vendors of haircuts, beer, drycleaning, sparkplugs and the like. Next to the drugstore is a lunchroom decorated in early Andy Hardy maltshop and down the street is a first-class rib joint. The rest of Xenia Avenue is almost a roadmap of our postwar cultural fashions. The beatnik fifties are represented by the wonderful Little Art movie which is both little and arty. Up the street is the always marginal art gallery. The turbulent sixties left a genuine “head” shop and the Big Bill Hayward bookstore which is named after the famous Wobbly and was keeping erratic hours this summer. The whole grain seventies show up at the organic grocery, the organic restaurant and the shops of the crafters-the beaters of gold, the throwers of clay, the dippers of wax, the weavers of wool, the cutters of stained glass.

The News is down a short alley from Xenia Avenue, between a silversmith and a wood carver.

Before the woodworkers moved in, the front of the building used to be the domain of F. Faye Fluke, who, with his wife Edna, held the political plumb of Registrar of Motor Vehicles for the village. Whether it was a change of administration in Columbus or merely the ravages of time, the Flukes are gone. The News occupies what was once the garage of the local Chevrolet dealership.

The history of the village, the college and the newspaper intertwine. The village’s first attraction was its namesake mineral springs that in the early days drew the ill and the weary from as far away as Cincinnati. The healthy image even attracted an extremely shortlived Owenite utopian community to the springs. Antioch College was founded in 1852 by local promoters in league with local Unitarians. Horace Mann was the first president, coming to this frontier backwater fresh from his triumphs in reforming the Massachussetts common schools. Mann was a platform orator of some note, even in un-amplified mid-century America. He was known as the “Great Thunderer.” Mann insisted, to the great scandal of the surrounding countryside, that Antioch admit women and blacks. The college’s ruinous finances were the death of Mann but in his final oration when the grim reaper was already at his elbow, Mann burned the reforming gospel deep on the college’s soul with the exhortation, “I beseech you to treasure up in your hearts these my parting words. Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” Mann was buried on the front lawn of the college until his loved ones had him dug up and reburied in the more congenial soil of Massachusetts. But Mann started a pattern that persists to the present for Antioch-lofty ideals and threadbare finances.

The college staggered from one crisis to the next until it collapsed into bankruptcy in 1920 and was bought lock, stock and barrel by another great reformer, Arthur Morgan. Morgan was a fervent Quaker, an engineer and a regional celebrity. He was a friend of the Wright Brothers and suggested the hilly pasture to them as the site for a flying field that is now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. After the terrible flood of 1913, Morgan helped design the Miami Valley Conservancy District. He later left Antioch to become the first head of the Tennessee Valley Authority until he quarreled with Roosevelt over the direction of that great experiment In regional development.

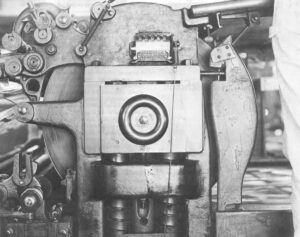

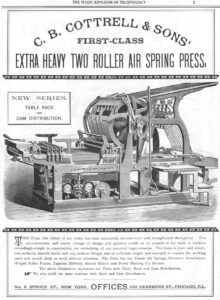

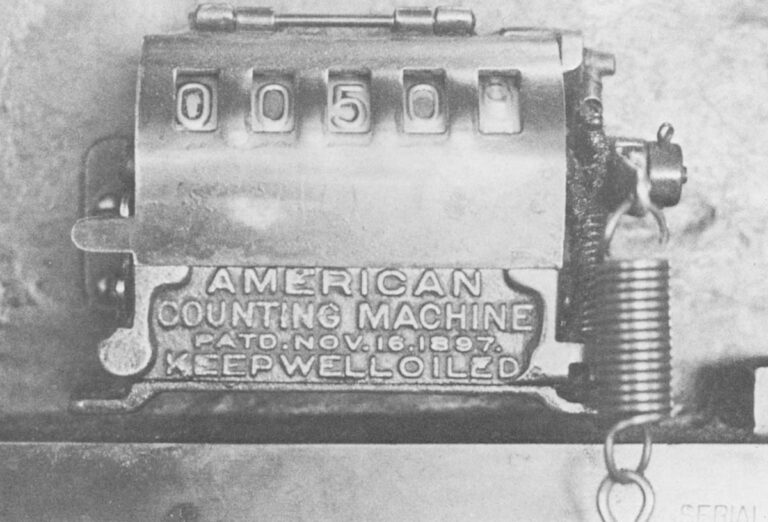

Morgan believed that work and study together would form the character of Antioch’s students. It was also the only way to keep the institution going. Besides maintaining the college grounds and buildings, students staffed the college press and ran a shoe factory that made a model known as the “Antioch Shoe.” Morgan also founded the Antioch Bookplate Company which continues today in family hands. In the process of acquiring the buildings and equipment for the Bookplate Company in the early 1940s, Morgan picked up the assets of the Yellow Springs News, a weekly that traced its undistinguished heritage back to 1880. Morgan hired a young Christian pacifist named Keith Howard as editor. The paper was a continual drain on the Bookplate Company so it was sold to Howard and Leland Bullen who was the printer. The News consisted of the name, an antique Babcock single revolution press and an old Model Five linotype.

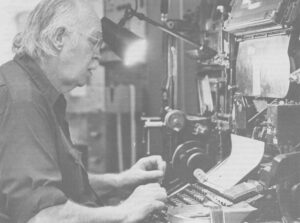

In 1949, a local Quaker boy named Ken Champney, finding himself “out of money and interest” in going to college, hired on as an apprentice printer. “Actually they tried me out as a Society Editor for one week before they decided I was a bust.” Champney knew little or nothing about printing but he remembers, “They obviously needed help as they were coming out a day late.”

Champney was a quick study and when Bullen left to take a better paying job as a typesetter in Springfield, Champney became chief printer and part-owner. From the beginning, the News was Ken’s entire life but instead of deserting his family for the business, he brought his family into the business. “That’s why I married Peggy,” he says only half in jest, “She said she’d come in to help. I figured if she’d do that, she’d do anything.”

Peggy took over the printing of the News completely from 1952 to 1954 when Ken was sent to Ashland Federal Penitentiary in Kentucky as a conscientious objector. When he got out, the, cold war had moved even closer to home. A group of local conservatives angered by the pacifist and liberal stance of the News put up the money for a rival weekly patriotically called the Yellow Springs American. After a modest start, the American went in for red-baiting in a very big way, denouncing Antioch as a Bolshevik nest of treason and demanding a congressional investigation. Frightened by the increasingly bloodthirsty editorial tone, the chief backers withdrew and the Yellow Springs American died, aged 10 months. The competition was good for the News. It was forced to increase its news coverage and run more pictures. More importantly, the villagers saw that whatever its quirks, the News was the local paper and the short-lived American the outside agitator.

Peggy took over the printing of the News completely from 1952 to 1954 when Ken was sent to Ashland Federal Penitentiary in Kentucky as a conscientious objector. When he got out, the, cold war had moved even closer to home. A group of local conservatives angered by the pacifist and liberal stance of the News put up the money for a rival weekly patriotically called the Yellow Springs American. After a modest start, the American went in for red-baiting in a very big way, denouncing Antioch as a Bolshevik nest of treason and demanding a congressional investigation. Frightened by the increasingly bloodthirsty editorial tone, the chief backers withdrew and the Yellow Springs American died, aged 10 months. The competition was good for the News. It was forced to increase its news coverage and run more pictures. More importantly, the villagers saw that whatever its quirks, the News was the local paper and the short-lived American the outside agitator.

Kieth Howard edited the News according to his convictions. Hometown boys In the service received equal billing with pacifist speakers addressing the local Fellowship of Reconciliation. Over and over, the News came out against racial discrimination, nuclear weapons, war and liquor. This was not merely knee-jerk suburban liberalism. Many residents were career Air Force who worked in the Strategic Air Command at Wright-Patterson. They took the News’ ban-the-bomb pronouncements personally. Well into the 1950s, the public racial manners of Yellow Springs were those of a small southern town. Things were never as rigid or openly hostile as they were in Xenia where the Klan was rumored to have a following but the rigid code of small town segregation made certain Yellow Springs restaurants, job, and services off-limits to blacks.

This, of course, infuriated the children of Stevensonian liberalism at Antioch. In 1962, demonstrations against a local barber who refused to serve black, spilled over into it wild traffic-blocking “confrontation” between students and police that briefly made the national headlines. The barber shop riot was a sort of out-of-town preview of the civil rights clashes soon to come in the South. In its reporting, the News played the racial turmoil close to the chest but the editorials thundered the brave and righteous truth. Great issues in small towns have a way of jumping unexpected fences to strain friendships and hurt business. The civil rights issue cost the News ads and subscriptions but the people who ran the paper could see no other course.

Time and causes change. In 1976, the News decided it would no longer list meetings of the local gay activist association. Great was the anger of the gays and their supporter before the News struck its colors. The paper occasionally rubbed local opinion the wrong way on less cosmic issues. When the village water tower burst during the savage winter of ’77, Ken loosed off an ill-tempered attack on the new village manager that all but blamed him for the cold. When the second Ken saw his editorial in print, he knew he had gone too far and immediately drafted a retraction and an apology. But local writers had already taken up the cudgels. The letters column smoked for weeks. It was a clear case of the arrogance of the News, the correspondent fumed.

Under Kieth Howard, the News was ardently prohibitionist. Until recently you could not buy hard liquor in any form in the village. License applications to sell beer and wine were gone over in print with a fine tooth comb by Kieth. When a local beer merchant ran afoul of the state sales tax collector, it was front page news again and again. To this day, Kieth gives a vivid dramatization of the New Year’s Eve 1938 when he consumed the last beer of his life and swore off the demon brew forever.

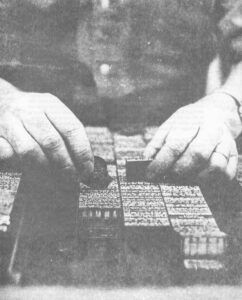

Headlines had a peculiar ring to them–“Easter is Observed” being my favorite. Kieth also had his own priorities. One Wednesday afternoon, I strolled into the eerily quiet pressroom to find the make-up man standing by the stone with his fist holding open an enormous hole in page one. A poetic friend of Kieth’s was wrestling with the last stanza of an ode to autumn in the front office. Disgustedly, the make-up man explained, “We’re holding for a late-breaking poem.”

Kieth Howard retired in 1976 to loud choruses of praise from friends and former foes. For over 35 years, Kieth was the News and when he left, the whole burden fell on Ken Champney who became editor, publisher and printer. Even for a manic worker like Ken, it proved too much. Long deferred decisions about the future of the News had to be made and chief among them was the question of converting cold type composing and offset printing. In 1969, the News made a study of the question and concluded that hot lead was still viable but recommended a re-consideration in five years. The changing of the guard came at the time when the case was called again.

As chief active owner, Ken was forced to concede that he could not carry on under so many hats. New blood was needed in the editorial office. In the shop, either a young hot lead printer had to be found at the low News wages or a cheaper and easier production method had to be introduced. As it turned out, the choice of a new editor settled the hot lead issue.

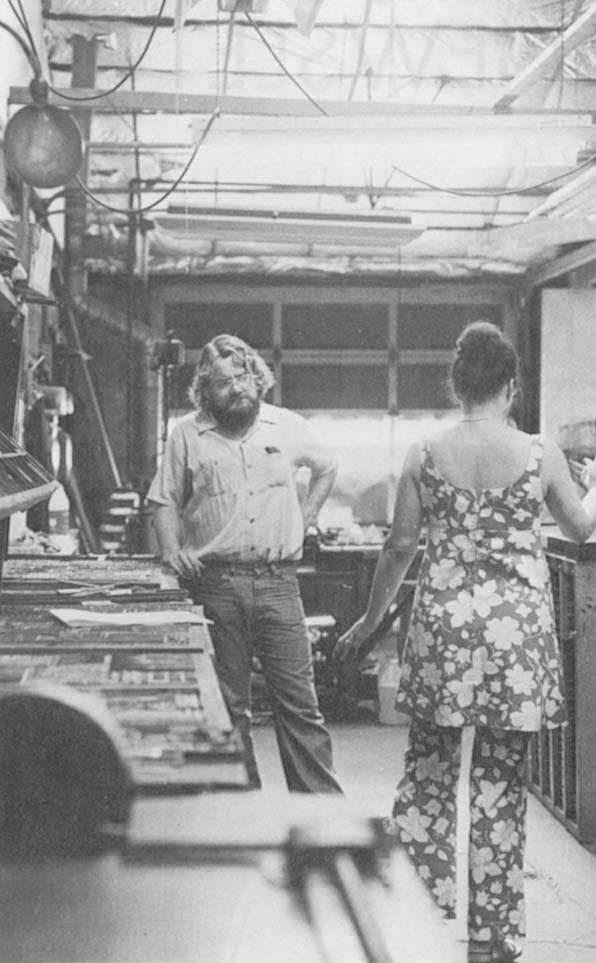

Don Walls is the third generation of newspaper editors and owners. His family runs a daily and a string of weeklies in southern Indiana. Don was editing the Vevay Reville-Enterprise in a picture postcard town near the Ohio River. Don is a barrel-chested, full-bearded man who looks like he slipped ashore from a pre-Civil War river raft. In his soft drawl, Don comes over as a gentle, thoughtful, almost poetic newspaperman. Don wanted his little girls to grown up in a slightly more cosmopolitan area than Vevay. Vevay is called the New Switzerland of the Ohio Valley because of its rugged scenery and its isolation. He was pleased with what he saw of Yellow Springs and of the possibilities of the News. And like most editors his age, his experience was totally in cold type production.

The Reville-Enterprise had long been offset. The labor savings of jobbing out the capital-intensive printing are especially attractive to small papers. The number of advertisers and subscribers in a rural area is limited so cutting back on fixed costs is virtually the only way small papers have of coping with inflation. Contrary to the expected order of things, the new technology of printing was taken up first by small dailies and weeklies, leaving the giants to wait for the technology to catch up with their more complicated requirements. Today the number of hot lead papers of any size is shrinking fast. In the summer of 1977, it was the turn of the News. Don Wallis bought in for a third share of the News and with the understanding that the paper would eventually go offset. Once that decision was made, the eventuality came on much faster than anyone had imagined.

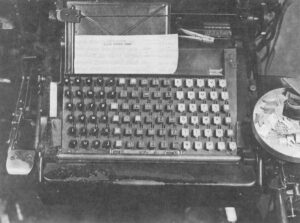

To say that the News was going cold type was to put a grander name on it than the reality allowed. The successor to the faithful linotypes is a very second hand compugraphic photocompositor that runs on punch tape. Pasted to the side of its scratched gray cabinet are curling cardboard charts of set sizes from its last shop. Well worn but functional, the Compugraphic fits right into the decor of the backshop. Only the small light-tight box where the type is exposed on film marks it as alien from the race of hot lead machines around it.

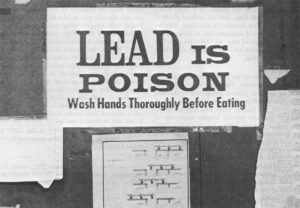

The cold-type conversion gathered steam. One Thursday afternoon, Don Wallis cleared off space on the mailing table for one of the recently assembled paste-up easels. On hand for this look into the brave new age were Julie Monroe as the advertising department and Dot Thomas as the soon-to-be-created paste-up department. Don taped down a paper dummy and then picked up the hand waxer that had just come in the mail. The wax holds everything in place but the little gadget which melts the wax pellets refused to heat up. Dot suggested parking it on the back of a linotype lead pot. It worked for soup cans, Dot said, although she recalled that the old timers who threw raw potatoes into the molten lead had a way of dying of lead poisoning.

The cold-type conversion gathered steam. One Thursday afternoon, Don Wallis cleared off space on the mailing table for one of the recently assembled paste-up easels. On hand for this look into the brave new age were Julie Monroe as the advertising department and Dot Thomas as the soon-to-be-created paste-up department. Don taped down a paper dummy and then picked up the hand waxer that had just come in the mail. The wax holds everything in place but the little gadget which melts the wax pellets refused to heat up. Dot suggested parking it on the back of a linotype lead pot. It worked for soup cans, Dot said, although she recalled that the old timers who threw raw potatoes into the molten lead had a way of dying of lead poisoning.

Eventually the wax was prevailed upon to work. Taking a test galley of type produced by the Compugraphic, Don carefully trimmed the strip to size, waxed the back and pressed it into place on the dummy. A little Jiggling with a T square and an exacto knife followed. Voila. The story was pasted up. Dot laughed at the simplicity of it. “It’s going to be fun. It’s going to be just like working with paper dolls. When I was a kid, we had these little hats and dresses that we pasted on cutouts. It’ll be like going back to my childhood.”

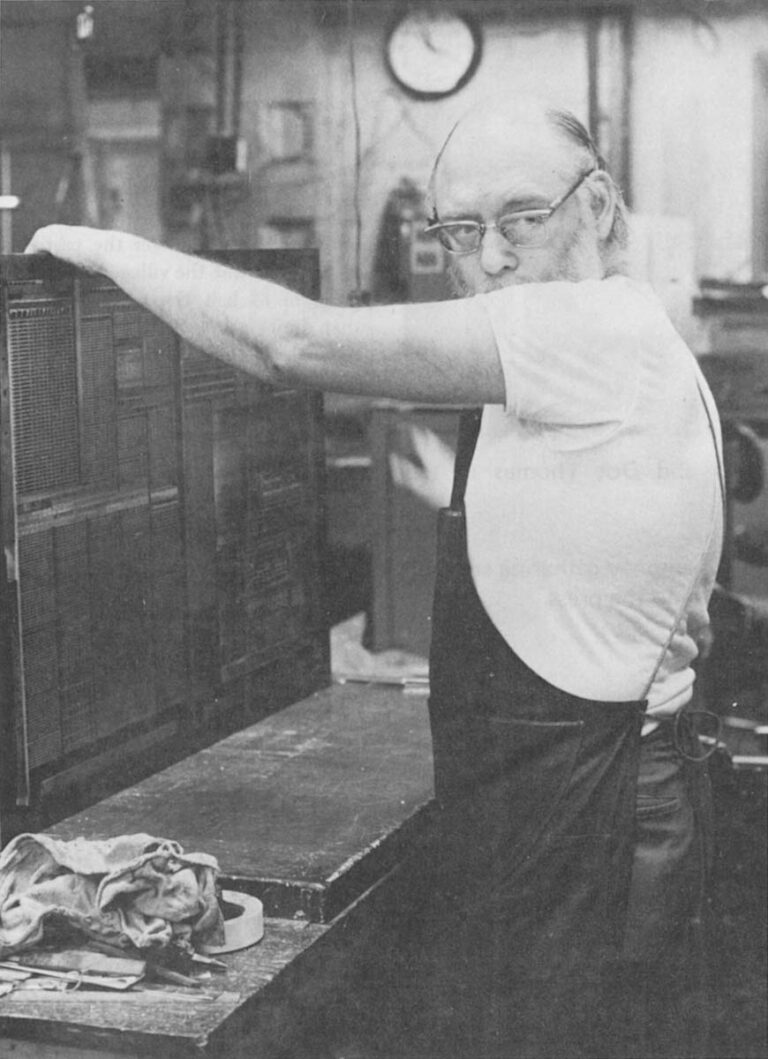

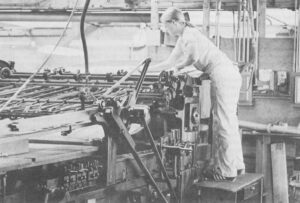

Dot’s childhood was a little different from that of the average paster of dolls coats and dresses. Her father ran his own print shop and when Dot was 12, her father stood her up on a wooden box and set her to feeding a press. All through her teens, she learned her father’s trade. She enjoyed the work and besides, she earned her clothes money right through high school. Now, she has worked 27 years as a full-time printer in a variety plants including job shops, a poster printer who did promotions for stockcar and motorcycle races, even a stint setting news and classifieds at the Springfield Daily News where she held a union Card from ITU Local No. 117. The money was good but money isn’t everything. “Up there, it was a steady push to get the paper out. You didn’t have any free time.”

Dot’s childhood was a little different from that of the average paster of dolls coats and dresses. Her father ran his own print shop and when Dot was 12, her father stood her up on a wooden box and set her to feeding a press. All through her teens, she learned her father’s trade. She enjoyed the work and besides, she earned her clothes money right through high school. Now, she has worked 27 years as a full-time printer in a variety plants including job shops, a poster printer who did promotions for stockcar and motorcycle races, even a stint setting news and classifieds at the Springfield Daily News where she held a union Card from ITU Local No. 117. The money was good but money isn’t everything. “Up there, it was a steady push to get the paper out. You didn’t have any free time.”

By free time, Dot means working on her own and at her own pace. Take ad make-up. Dot marks up her copy, sets the varied faces and sizes from the Iinotypes and then saws and leads and tapes and mitres the whole together. Free time also includes the supply and clean-up chores-breaking up old pages, straightening up the stones and slug racks, distributing handset type-that keep the shop from running out of vital materials or strangling on its own debris. Free time and the congenial workmates at the News were the attractions that brought Dot back from Springfield to the Yellow Springs News. Now Don’s little waxer was going to relieve her of a lot of her free time chores but she figures that she will learn to live without all the fussing that hot lead requires. “It’ll be great. All your do is paste things down. You don’t have to saw your slugs, cast your mats, keep your slug racks filled. It’s going to be a lot easier.”

By free time, Dot means working on her own and at her own pace. Take ad make-up. Dot marks up her copy, sets the varied faces and sizes from the Iinotypes and then saws and leads and tapes and mitres the whole together. Free time also includes the supply and clean-up chores-breaking up old pages, straightening up the stones and slug racks, distributing handset type-that keep the shop from running out of vital materials or strangling on its own debris. Free time and the congenial workmates at the News were the attractions that brought Dot back from Springfield to the Yellow Springs News. Now Don’s little waxer was going to relieve her of a lot of her free time chores but she figures that she will learn to live without all the fussing that hot lead requires. “It’ll be great. All your do is paste things down. You don’t have to saw your slugs, cast your mats, keep your slug racks filled. It’s going to be a lot easier.”

What she’ll miss most is the noise of the linotype. “When a machine’s running, there’s a lot of noise and I guess I’m used to it.” Cold type means the end of her labors at the tablesaw or the stone but it isn’t the end of the world for Dot. Cigarette dangling from her lip, she hefted the little waxer in her hand. “I look forward to changes. I haven’t reached the stage where I can’t learn something new.”

The text was set on an IBM Composer and the headlines on a Varityper by Mrs. Hazel Richmond at the UCLA Department of Journalism, Los Angeles.

Photographs and layout by John Fleischman.

Proofread by Louis Watanabe.

TO BE CONTINUED

©1977 John W. Fleischman

John W. Fleischman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from Human Behavior Magazine. His fellowship subject is “The Medium of Print: A Craft Becomes a Computer Function.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Fleischman as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to Human Behavior Magazine. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.