Madison, Wis. — Dr. Victor Wayland is a cheerful man, the kind of children’s dentist who makes you wish you could repeal your dental history and start over with a new set of baby teeth.

The fact that he’s sold on behavior modification as a tool of his profession might seem odd, if you imagine behavior modification to be the robot-producing brand of medical terrorism portrayed in popular literature. But Dr. Wayland believes that a big part of successful dentistry involves overcoming the fear and trauma that make people avoid dentists and neglect dental care far into their adulthood. And he is now persuaded that the use of scientific behavior management principles is the most effective way to help children cope with those fears and learn about their bodies.

“It’s civilization,” he says, “it’s not punishment. It’s helping children to use their rational powers rationally, and it’s beautiful.”

Dr. Wayland is risking something in making statements like these in Madison today. Behavior modification in children’s dentistry is a controversy. Another pedodontist, Dr. William Mortell, is currently awaiting judgment on charges of unprofessional conduct for allegedly striking children in his office, inflicting bruises, black eyes, and bloody noses, and calling it “behavior modification.” Four children aged four to seven testified before the Wisconsin State Dental Examining Board in November that Dr. Mortell struck them during treatment. A mother of one of the children said she protested the alleged abuse and received a “lengthy lecture on behavior modification” from Dr. Mortell.

Behavior therapists at the University of Wisconsin were scandalized by the case and six of them issued a public statement disassociating themselves, and behavior modification, from any practice involving violence against children. Dr. Mortell denied the charges and a hearing examiner backed him up, discrediting the testimony and recommending dismissal of the charges. Dr. Mortell has declined to explain his views on behavior modification to reporters, saying they are “too complicated.”

Dr. Wayland’s views on behavior modification are not simple, but they are clear. He agreed to discuss them in order to clarify the issues and explain procedures which are receiving increasing attention in the professional literature. Dr. Wayland received his training in behavior management at the University of Wisconsin as part of his studies in communicative disorders. (He is a doctoral candidate. In addition to his regular practice he lectures at the UW Medical School, serves on the staff of three Madison hospitals, and does research and clinical work on children with cleft palates).

“When you’re talking about behavior modification you’re on touchy ground,” he says. “You have to be specific that it’s in terms of getting a job done and not of changing children’s lifestyles in the least. The goal of pedodontics (children’s dentistry) and preventative dental treatment is to prevent disease, oral disease in this case. The goal is treatment. What we’re interested in is getting Johnny to accept this treatment and the need to go on with it.”

The first step, Dr. Wayland says, is to find out just how well prepared a child is to accept novelty — new people, new settings. He checks this out in a preliminary interview. The result is a behavioral assessment.

“We’re working with many variables and we have to find out what they are,” he says. “Our assessment actually starts with the phone call the mother makes for an appointment. Is she belligerent? Is she worried? If there is something here, my receptionist gives me notes on it. I also have the report from the referring pediatrician or dentist. But you have to weigh all of these things without prejudice and pay attention to what happens when the parents and the child are in the office.”

Dr. Wayland’s office is like a den, a small room with bright furniture and books. T here is a couch, a desk, and a chair next to the desk. “It’s a homey room and I dress casually,” he says, “but I do sit behind the desk. I don’t want it to be so relaxed that my leadership of the situation is not plain.”

“I welcome the parents and invite them to ask questions. They’re in charge of Johnny’s health and it Is their responsibility to find out what a doctor is like — what his goals are, what his techniques are, what kind of person he is. Then I might make a statement on what is going to happen that day — we’re going to look at Johnny’s teeth, we may take some pictures of his teeth, we’ll clean his teeth, and he’ll get to know me.”

“Then I’ll make a direct command to the child and say, ‘Now, Johnny, come over here and sit next to me. I want to look at your teeth.’ What happens then tells me a lot. Sometimes the mother will pick the child up and carry him over to the chair. Sometimes the child will jump into his mother’s lap and start screaming. Or, he may hop up very boldly into the chair and open his mouth. It’s important to find out how the child reacts to meeting a stranger and how he takes direction. By making this command I can ascertain what kind of learning has gone on, what social skills the child has, and something of what the parents are like. Often the parent has been the child’s sole teacher up to this point. This is the time, then, for some new teaching to help the child cope with a new teacher.”

If Johnny is cooperative, Dr. Wayland checks his teeth, his bite, and his general oral health briefly and gives the parents some preliminary information. Then he takes Johnny to the treatment room.

However, “if the child reacts inappropriately and the mother doesn’t react appropriately, I halt the whole show right there,” he says. “I buzz for my dental assistant. I tell her to come in and take Johnny out to show him around the office while I talk to his parents. Then I repeat the instructions to Johnny: ‘Barbara is going to come in. She is going to show you around the office. I am going to talk with mommy. Then I’m going to clean your teeth and I may take some pictures of your teeth. Mommy will be waiting here for you. When we are finished you will get out of the chair and go home with mommy.’”

Once Johnny has been taken out and it’s quiet again in the office, Dr. Wayland asks the mother what caused Johnny to react like that in his homey office. “There’s nothing strange here. There are no funny smells. I look like a daddy. I’m not wearing a white coat. Why does she suppose he reacted like that?”

Finally, he says, it will come out: “Well, I did tell him you were a doctor and I told him what kind of doctor you were.”

“I feel them out to get feedback on their own fears of dentists, their own learning history,” Dr. Wayland says. “But I don’t spend too much time on this. It’s Johnny’s treatment time, not theirs. So I will explain to them that these are not hurtful procedures. I assure them that I will take the pain away. And I will suggest that if Johnny is crying through a new experience even though he’s not being hurt, it may be that Johnny has learned to manipulate adults with this behavior. Johnny is intelligent, he is not ill, he is not retarded, he can cope. His behavior is not bad, it’s just inappropriate.” (Like all behaviorists, Dr. Wayland sees responses as “appropriate” and “inappropriate.” “I never make moral judgments,” he says, “you can go to a priest or rabbi for that.”)

“‘If Johnny has learned to cry to manipulate, it has to end here,’ I tell the parents, ‘because he cannot manipulate this situation if we are to reach our goal.’ Usually this turns light on,” Dr. Wayland says.

He gets a broad, signed permission from the parents before he uses any behavior management techniques with the child. “It’s a terrible responsibility,” he says. “You’re taking a little darling of someone’s and doing what you think is necessary.”

The techniques Dr. Wayland uses are applications of “operant conditioning” theory which holds that behavior is shaped and maintained by the immediate consequences that follow it. If, for example, Johnny sits screaming in the chair and succeeds in getting the dentist to throw up his hands and ask Johnny’s mother to take him away, Johnny is actually being rewarded (reinforced) for screaming. “He’ll learn to scream even louder the next time to get the dentist to give up even quicker,” Dr. Wayland observes.

So Dr. Wayland takes steps to show Johnny that he can’t gain his goal of escaping by screaming. “You may have to hold his legs, steady his head, and let him scream it out,” he says. “The important thing is to set limits — to show Johnny that this behavior just isn’t going to work.”

The next step is crucial. “You go to work in an orderly fashion. You teach him your predictability. You have told him what you plan to do. You must now do it. Your behavior must be predictable and consistent. The most insecure children I’ve seen are those who have an inconsistent parent, model, or situation around them,” Dr. Wayland says.

In a few extreme cases where children have become uncontrollably hysterical, Dr. Wayland has used a technique known in the professional literature as Hand-Over-Mouth Exercise, or HOME. “A psychiatrist dealing with a hysterical adult can slap his face, but children are not capable of receiving a slap like adults,” Dr. Wayland says. “There are ways of helping a hysterical child without resorting to slapping him. The ‘hand-over-mouth’ method is very effective but it is used very, very seldomly. I can hardly remember the times I’ve done this. If you are using the technique you must have the parent’s permission, although I will not harm the child in any way. That’s not what he’s here for.

“The idea is to quiet the child while you’re talking in the child’s ear. It’s difficult to calm the child unless you can get his attention. So you hold your hand over his mouth firmly and say, ‘I want to take my hand away but I can’t until you stop screaming. You can’t hear me if you’re screaming.’ You have to be very calm and stable about this. You ask him to nod if he’s ready to stop screaming and when he nods you take your hand away. Then you proceed without mentioning the screaming. It’s a thing of the past, and now you’re rewarding cooperation again.”

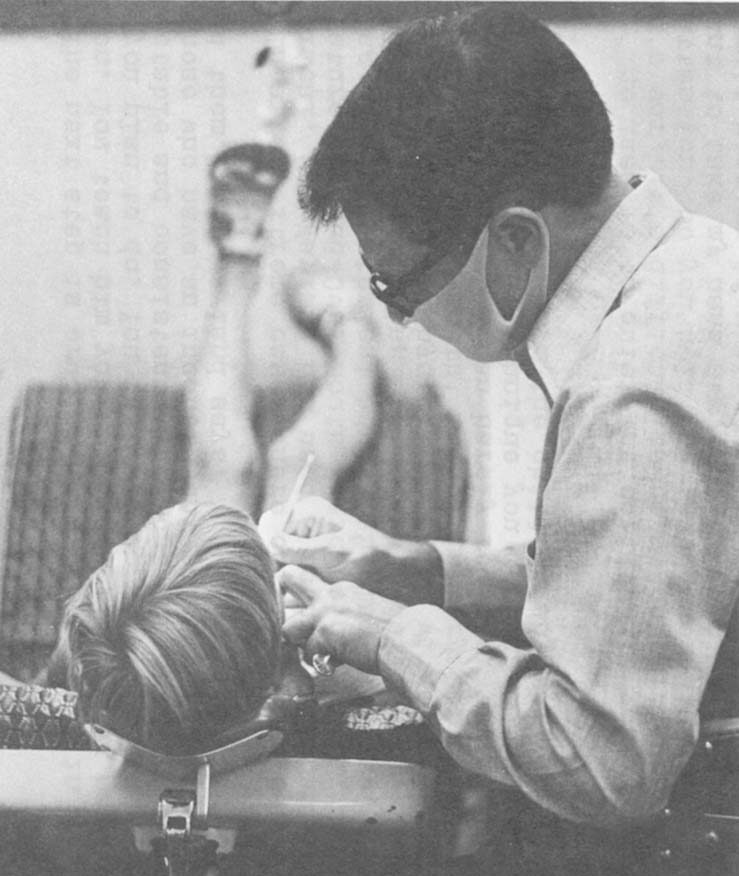

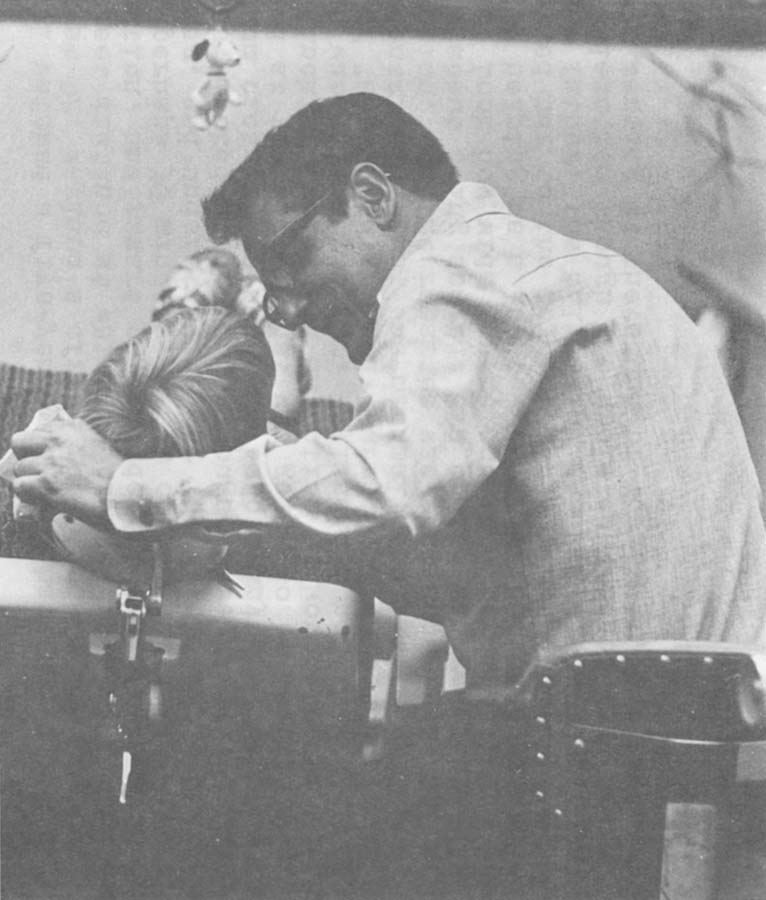

I watched a five-year-old girl have her first major dental work at Dr. Wayland’s office recently. It was obvious — from the discreet distance at which I observed it — that continuous information, attention, and reward pay dividends. The office procedure, which took perhaps 30 minutes, was a continuous experience of touching, looking, and understanding for the little girl. She touched her x-rays, looked at where the “bugs” were, felt the water stream and “vacuum cleaner” on her hand before anything happened in her mouth, looked at the silver that was going to be her filling. There was no flinching during the injection of Novocain or during the drilling, which was extensive. (Dr. Wayland did not talk of “needles” or “drills,” but of “sleepy water” and “burrs.”) The doctor’s communication with his dental assistant was minimal; the little girl was the center of attention, and the repartee was continuous; she had no time to think about being scared. His praise was generous — “Hey, you’re great! Look how wide you’re opening your mouth! You know, you’re really helping us a lot to get those bad bugs out.” At the end he escorted her to the toy box to pick out a prize. As he praised her to her father, the only thing she wanted to talk about was her new toy. Her relaxation through the whole experience was remarkable. I found myself tensing at the sound of the drill, but she was almost blissful.

Dr. Wayland enjoys beginning dentistry with children around the age of three. “Three is a beautiful age for most children,” he says. “They’re so teachable. They can rationalize. They can be worked with for 15 to 20 minutes at a time. It can be an hour as long as you take the pain away. I tell parents that if their child comes to school looking ill, the teacher will send him home. The teacher is not going to try to teach him anything. The same goes for children here: if their child is in pain while we are trying to treat him, we can’t teach him anything either. So we take the pain away.”

Dr. Wayland, however, opposes pre-medicating children with tranquilizers or nitrous oxide gas, and he reserved general anesthesia for children who must be hospitalized — severely retarded children, physically handicapped children who cannot assist the dentist, and emotionally disturbed children.

“I want my children there and learning,” he says. “I want them sharp. I will take the pain away. The other drugs are there as tools if we need them. But I’ll always try the natural way (using only local anesthetic) first.”

Thumbsucking: Behaviorists Put the Bite on Dr. Freud

The correction of dental problems caused by thumbsucking is one of the most interesting issues in children’s dentistry because it involves direct aversive techniques and because it brings dentistry into a direct collision with the traditional assumptions of Freudian psychology.

Freud held that thumbsucking is instinctive in early infancy, but that if thumbsucking continues into late infancy and early childhood it is a sign of emotional disturbance. He also held that “breaking” a child of thumbsucking will bring trouble in the form of “symptom substitution” — the child will replace the thumbsucking “symptom” of his emotional disorder with another pathological “symptom” like tantrum behavior or masturbation.

Dr. Wayland, and a growing body of professional literature, says this is bunk. “We went through a terrible phase when Freud had us so bugged we were afraid to do anything for fear of hurting a child’s psyche,” he says. “The research shows that ‘symptom substitution’ is a myth; it just doesn’t happen. We know a lot about intrauterine development today. For the organism to survive, the perioral (mouth) region must be highly developed, to allow the child to cry for help, to eat, etc. The mouth becomes a very pleasurable organ very early. It’s for survival. How easy it is to suckle anything that comes into range! And how easy it is for this to become habitual. What I’m trying to say is that thumbsucking does not necessarily mean a child is emotionally disturbed.”

Thumbsucking can cause serious health and speech problems in some children. The alignment of teeth and the bite depend on a balance of muscle forces, with the lips pressing in and the tongue pressing out. Thumbsucking creates a tremendous drag on the upper jaw and can throw the muscle balance out. The jaw grows outward, the teeth move out, and an opening develops. The child may begin to lisp and thrust his tongue out to fill the hole. The jaw searches for a bite and sometimes finds it only by moving sideways into a “convenience crossbite” which throws the jaws out of line.

“Sometimes I tell parents to let the kid do it for a while. He may have great muscles to bring his mouth back into line,” Dr. Wayland says. “If he has weak lips, we can exercise them by giving him a button on a string and having him hold the button between his lips and tug on it.”

If the problem is advanced, a formal behavior modification procedure may be indicated. Again, Dr. Wayland assesses the family situation before he moves ahead. “If I have a kid who has nothing but his thumb — his father and mother obviously don’t give a damn about him, or you can see other stresses — there’s no way I’m going to remove that thumb! I’m not going to take his thumb away if that’s all he’s got. You can always do corrective surgery later.

“And if you can see that his parents aren’t going to give him support through this treatment — if he has the kind of father who says, ‘No son of mine is going to suck his thumb’ — then you might as well stop right there because it’ll be a failure.

“But if you decide you want to start therapy and you’re dealing with supportive parents, you begin by having the child study models of his mouth and compare them with models of a normal mouth. ‘Look how crooked it is, and look at this big hole.’ you tell him. ‘If you fall off you bicycle, see how easy it will be to break your teeth?’ The kid looks and says, ‘Yeah, I can see that.’ Most kids are inquisitive and want to help.”

Then Dr. Wayland installs an appliance, a “palatal crib with spurs.” (See photo, p. 7.) It is a wire banded to the back molars which runs around the inside of the upper jaw. At the front of the mouth, behind the front teeth, five fork-like barbs stick down.

“The barbs are not sharp enough to cut tissue, but they are sharp enough to deny the thumb contact with the roof of the mouth,” he says. “They are also bent and curved to retrain the tongue to stay back in the mouth.

“The appliance is a deterrent. It is effective in both waking and sleeping hours. The thumb gets a message at all times.”

Dr. Wayland prepares the child for the experience of wearing the device. “’I know it’s hard to keep the thumb out of your mouth, just like it’s hard for your daddy to stop smoking,’ I tell him, ‘so I’m going to make something to remind you to keep the thumb out,”‘ he says. “Kids are rational; they see the connection.” He also gives the parents instructions on how they can support their child emotionally through the experience. (Many parents are already expert at this, he says, and he enthusiastically promotes parent training programs).

The habit stops almost immediately, he says, and usually the problem is corrected within six months. “When the appliance comes out it’s a happy day,” he says. “The child is the center of attention: ‘Hey, look what you did! Aren’t you proud? You did it all yourself!”‘

Many things are possible with the use of behavior management techniques, Dr. Wayland says, and the reason is that such techniques emphasize the capacity of children to learn. “People forget that kids are reasonable,” he says. “I can’t say that I have ever had an unreasonable kid. I’ve had obnoxious kids, but after a few sessions they change when they walk past the door into my room. I never spend much time conditioning any child.”

Discussion

The appearance of behavior modification techniques in children’s dentistry is yet another example of the widening scope and increasing penetration of the behavioral persuasion in everyday life. Principles which only recently were confined to laboratory testing and experimentation are now being popularly adapted by schools, corporations, institutions, and individuals like Dr. Wayland.

His profession is, of course, not psychotherapy but dentistry, and his approach to children does not represent a “model” of behavior modification. His use of behavioral principles is selective; together with a good deal of common sense and an orientation toward child growth and development, they merely complement his dental practice. The things he tells children to demystify their dental experience are not necessarily “behavior modification,” but the way he reduces anxiety and disruptive behavior to pave the way for learning certainly is. Also, his awareness of environmental stimuli and his perception of parents’ and childrens’ behavior as response patterns created and maintained by definite patterns of reinforcement are very much in the behaviorist mold. Such a perception allows him to manipulate the environment and “rearrange the contingencies of reinforcement” to bring about change, rather than resigning himself to deal with children who are “unexplainably” and “constitutionally” difficult or fussy.

Dr. Wayland calls behavior modification “civilization,” and in some respects there is a good case for the descriptive. In his practice, at least, behavior modification seems to be a means of making the child patient more of a subject and less of an object. Because Wayland uses behavioral techniques the child need not be drugged into semi-consciousness or unconsciousness. During his treatment the child is alert to everything that is happening and he learns about the maintenance of his health rather than being alienated from the care of his body by fears and fantasies. It could be argued that the dentist who operates in the child’s mouth but neglects the child’s understanding of his mouth and the dentist’s relation to it is unscientific and probably less than professional.

Still, there is the question whether behavior modification does not really objectify the child by manipulating his responses to suit the doctor. The first part of the answer probably is that it is romantic to insist that a child have the freedom to refuse medical treatment or make serious judgments affecting his health. Until a child has the information and maturity to make those judgments, parents must make them. Dr. Wayland says he is careful to specify his goals and techniques to parents, and their consent is probably enough to eliminate the issue of manipulation at its basic level.

The second part of the answer to the question of manipulation is that Dr. Wayland deals with children through negotiation rather than by simple commands. He tells them what he wants, lets them know how they can cooperate, and rewards them when they do. He makes deals, and while the children cannot negotiate the basic activity that is taking place (except perhaps with their parents), they can make limited choices within the basic framework. (He will pause when they ask him to, and they can choose which side of the mouth they want him to clean first, for example). This is not autonomy, but neither is it dictatorship. It is soft authoritarianism, and that term defines parenthood as well as any.

Unfortunately, “soft authoritarianism” could also describe much of adult corporate and political life in the United States, and the most troubling question surrounding the use of behavior modification with children is whether it will train them to be good Orwellian citizens who “love big brother.”

One answer may be that much learning is “situation specific,” that learning to trust one kind of authority in one kind of setting does not mean learning to trust all authority in all settings. (Indeed, behavior therapists must learn special techniques to help their clients “generalize” their therapy gains — so that, for example, a person who has learned not to fear snakes in the woods will also not fear them in other places). So a child who learns to cooperate with Dr. Wayland may not cooperate at all with the dentist up the street, if the child perceives that the situation is radically different.

If there is enduring learning going on, it may be this: that Dr. Wayland’s patients are learning to cope with medical environments and personal health matters rationally and without anxiety; and that they are learning to behave reasonably in those environments with people who behave reasonably, consistently, and respectfully toward them.

Received in New York on September 12, 1975.

©1975 Ron McCrea

Ron McCrea is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin). This article may be Published with credit to Mr. McCrea, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.