Madison, Wis.–Put yourself in the situation:

You are having lunch with a friend when suddenly she asks you if you would lend her $30 until she gets paid next week. You have the money but you were planning to spend it for something else. She says, “Please lend me the money. I’ll pay you back next week.”

What do you say? Now try this one:

You are meeting with your co-workers to discuss a topic you feel strongly about. The majority of your peers disagrees with your position. The director of the meeting comments that time is running out and calls for a vote before you have spoken about your views.

What do you do?

If you handed over the money with a smile and let the vote go through without a word, you lack assertive skills and could profit from behavior modification training, in the view of professionals at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Behavior therapists do not prescribe tranquilizers or chat with you about your childhood experiences with authority. In their view your problem is not biochemical nor is it a “symptom” of an underlying personality disorder that must be excavated, like a lost city, from your past. Rather, they see your difficulty as a problem of learning. You have learned a set of responses that does not serve you well. The task is to help you learn a more useful set of responses.

“Assertiveness training” is but one application of the psychology of behaviorism now being tried at the University of Wisconsin under the auspices of the UW Family Health Service Counseling Unit and the newly-formed Wisconsin Behavior Research and Training Institute.

Other projects address problems ranging from migraine headaches and bedwetting to smoking, obesity, and family conflict. All of these are considered problems of training potentially within the command of the individual. They are, by definition, not illnesses.

Behaviorism, or “learning theory,” as its practitioners prefer to call it, sees human nature as chiefly a collection of learned responses. Behavior is shaped mainly by its immediate consequences in the environment; we gain our virtues and vices by being rewarded for them systematically and immediately. Reward, or “positive reinforcement,” is the most powerful dynamic in human living. Punishment, or “negative reinforcement,” is held by behaviorists to be less effective in shaping behavior than something that feels good, except in situations where punishment comes through as “attention,” which feels good in a bad sort of way. Such “punishment” may actually promote the behavior that the punisher is trying to stop.

Interestingly, behaviorists say that change does not require that the subject be oblivious to systematic rewards in order for new learning to occur. (Flattery, for example, is often effective even if a person knows he is being flattered). A subject can be fully aware of his own therapy without hindering it, because even consciously administered rewards are compelling when they are regularly delivered.

Behaviorism does not discount human will entirely, but it does hold out the possibility that a person–especially a vulnerable person in an institution–can be manipulated with or without his knowledge by anyone in a position to control the environment and deliver systematic rewards: a teacher, a parent, an employer, a prison warden, a government.

Behaviorism also suggests, on the positive side, that anyone with proper instruction can train himself to change in any way that he wants, purging the habits that impede his life, building confidence where none exists, and creating new options–the behavioral definition of freedom.

In the universe of behaviorism the human context writes the human text. The average individual is so little aware of the reward patterns that govern his life that his role is reduced to making minor revisions. With behavioral training, the individual can be raised to the status of co-author, and potentially can assume full authorship of his life. That is behaviorism’s promise. Its peril is that the individual will remain ignorant and that authorities will learn to use behavior systems to write their text on his blank page.

At Wisconsin, the humanistic promise of behavior training is evident, and the example of assertiveness training illustrates it well.

Recently three graduate students in social work, Sandy Stern, Shelley Krompier, and Nancy Weissman, met with a group of budding behaviorists and interested community people to discuss the results of a six-week assertiveness training workshop for professional women held this Spring on the UW campus.

Six women in professional jobs had answered an ad in a local newspaper announcing the workshop. At the first session the leaders made plain their operating values: “Every person has the right to be and to express himself, and to feel good (not guilty) about doing so as long as he does not hurt others in the process.”

They called assertiveness “behavior which enables a person to act in his own best interests, to stand up for himself without undue anxiety, to express his honest feelings comfortably, or to express his own rights without denying the rights of others.”

The leaders separated “assertiveness” from “aggressiveness” because “the aggressive person may respond too vigorously, making a deep and negative impression, and may later be sorry for it. A sense of worth is often lacking in the aggressive person, whose aggressiveness may mask self-doubts and guilt.

“The person who carries his desire for self-assertion to the extreme of aggressive behavior,” the leaders went on, “accomplishes his ends usually at the expense of others. Although the aggressive person may achieve his goal, he may also generate hatred and frustration which he will later receive as vengeance.”

The leaders were also forthright about the politics of their therapy with women. “Unassertive women are anxious and inhibited, let others make choices for them and don’t realize their own goals,” said Stern. “Society uses this unassertiveness to perpetuate the status quo and reinforce the idea of women’s dependency.”

The women in the group, then, were made aware immediately of what norms they were going to be conditioned to meet. The goals of therapy were announced and shared, not held back in a hidden agenda as a manipulator might hold them back.

The strategy of the assertiveness group leaders was to make the group a hothouse in which a new breed of behavior could grow amid the most protective and supportive of environments. Gradually the hothouse protections would be withdrawn and the now-hardy behavior would be transplanted into the real world.

The “gardening tools” for this workshop were fairly simple. A series of role-play situations was developed. Each member in the group would go through one role-play twice each session. The leaders would “model” each situation first by playing it out themselves. Then each member in the group would play out the situation themselves twice, with someone else in the group taking the role of antagonist.

After the first try the role-player would tell the group how she rated her satisfaction with the exchange, on a scale of 1-10. She would also rate her feelings of anxiety or distress from 1-10. (The anxiety rating was called SUDS, or “Subjective Units of Discomfort.” Behaviorists have an affinity for acronyms). If she felt she had gotten across what she wanted to say she would rate herself high in satisfaction; if she felt flustered or uptight at the same time, she would also rate herself high on SUDS. The assertive ideal was high satisfaction with low SUDS.

After the woman had rated herself, her antagonist would rate her on assertiveness from 1-10, offering specific praise and suggestions for improvement. Others in the group would follow suit then, giving the woman a great deal of feedback. With these rewards and suggestions in hand, she would try it again, rate herself a second time, and be rated and evaluated again.

In addition to the examples at the beginning of this article, the following were some of the devilish situations the women had to respond to:

You are one of five administrators in an office but the only one who is a woman. One of the secretaries of the supervisor just above you is going on vacation and he asks you to fill in as a typist.

You have just been promoted to the position of supervisor and a man who works with you says, “It’s great that you got the job, considering that you’re a woman.”

You have been waiting to pull into a parking space for several minutes. As the space empties, another car cuts in front of you and pulls into the space.

Your boss asks you to work late for the third time this week. You have an appointment this evening.

One of the professionals you supervise has not been handing in his reports although you have reminded him to do so several times in the past.

Sandy Stern and Shelley Krompier modeled an assertiveness situation similar to the last, in which a lab supervisor is having trouble getting her workers to clean the lab at the end of the day. She is to tell one of them to do it tonight. The exchange, feedback, and replay went like this:

Sandy: Um…we’ve been having a problem with the lab being pretty messy here at night. I’ve been asking people to try to clean up at night and I was wondering if…if you have the time, whether you could try maybe to clean it up.

Shelley: Yeah, well, I’m pretty busy.

Sandy: Yeah, well, it’s really a problem and I’ve been asking everyone to try to help out.

Shelley: Yeah, well, I’ll try to do something about it if I have the time.

Sandy: Okay, thanks.

Sandy: I guess my satisfaction is 5 and my SUDS is about 7.

Shelley: I’d give you about a 6 for assertiveness. You had good eye contact with me and you didn’t move your hands a lot. I would have rated you higher if you had made it more personal, used my name rather than telling me what you were asking everybody else to do. It would be better if you could give a deadline too.

Sandy: Those are good suggestions. Okay, let’s try it again.

Sandy: Shelley, the lab has been a mess lately and I want you to clean it before you leave work tonight.

Shelley: Yeah, it’s a problem but I’m pretty busy.

Sandy: I appreciate that you’re busy, Shelley, but I’ve been asking everyone to clean up and I want you to do it tonight before you leave.

Shelley: Okay, I’ll do it.

Sandy: Okay, thanks a lot.

Sandy: I rate myself a 9 for satisfaction and about a 4 for SUDS.

Shelley: I rate you a 9 for assertiveness this time. That was really good! It was good the way you used my name and set a definite deadline. Your eye contact was still good and you made me feel good about doing the job when you told me that you appreciated that I was busy. You still talked a little about how you asked other people to do the job, and it would have been better if you just kept it to me.

This exchange contained a number of “behaviors” which the workshop leaders consider to constitute the repertoire of assertiveness: Positive Affective Responses, or PARS (for example, “That was really good!”); leadership responses, including Direct Commands (“I want you to clean it”); and Suggestions (“It would be better if you could give me a deadline”). Other categories of assertive responses are Negative Affective Responses, or NARS (“I don’t like your attitude, Joe”); Indirect Commands (“Let’s begin, okay?”); and Refusal Responses (“I don’t want to go with you”).

During the workshop sessions observers noted these responses as the women exhibited them. It was one way to measure success: if the women uttered more assertive statements per hour with training, that was progress.

Between meetings the women became their own observers and behavior-counters. They kept diaries listing situations in which they were called upon to be assertive. They noted the setting of the exchange, their response or lack of it, their SUDS and satisfaction levels, their PARS and NARS and other assertive responses, and their feeling in the situation–anger, frustration, confidence, fear, whatever.

This kind of self-monitoring is commonplace in behavior modification therapy and serves several purposes. First, it puts the subjects into a scientific relation with their own behavior. They become trained really to notice what they do and how they’re reinforced. Second, self-monitoring serves as automatic feedback on progress or lack of progress, in the same way a bathroom scale shames or praises a dieter.

In the assertiveness group, self-monitoring also provided material for group discussion and support. The women brought their diaries to each session, discussed confrontations and their consequences, and received support and suggestions.

With these procedures in effect, it remained only for the group leaders to turn the screws. Beginning with the third session, the leaders turned the modeling and conduct of the meeting over to members of the group. In the fourth session videotape was introduced and the women could actually see themselves act out their roles on “instant replay.” In the fifth session, men unknown to the women were brought in to play the antagonists in the role-plays.

Intensifying the situation is another common behavioral technique. As the individual becomes progressively “desensitized” to anxiety-producing situations, the encounters are made more challenging. In many groups like this the last stage of training involves “field” experience. A nonsmoking group will go to a smoke-filled bar; a fear-of-flying group will board a plane and finally take a flight. The idea is to carry the support of the group into the final, most intimidating arena. Thus, introducing strange men into a women’s assertiveness group was raising the stakes about as high as they could go.

What were the results?

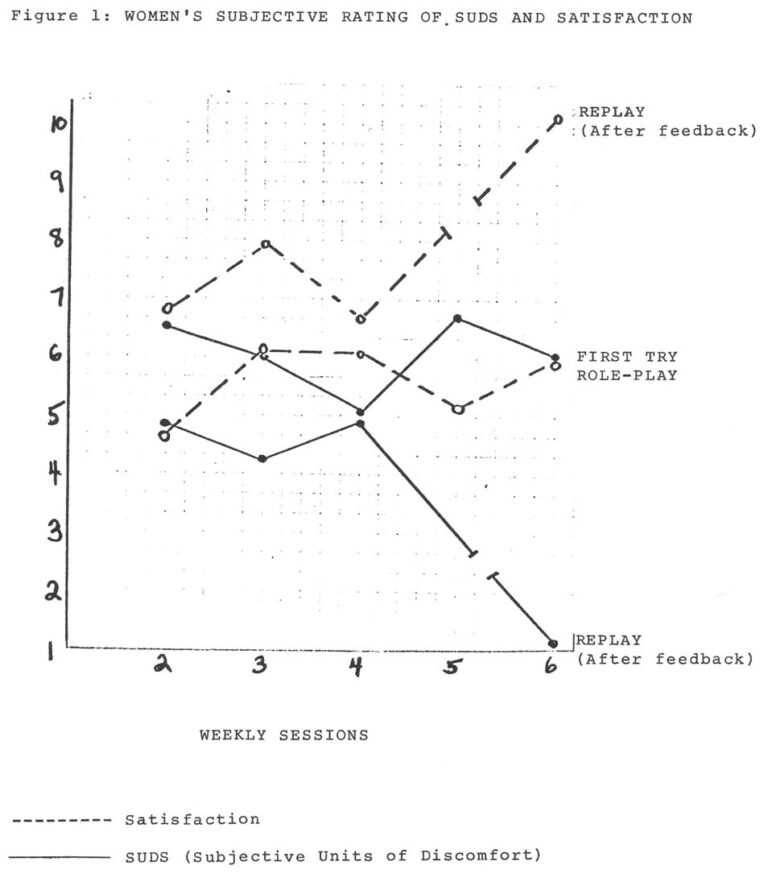

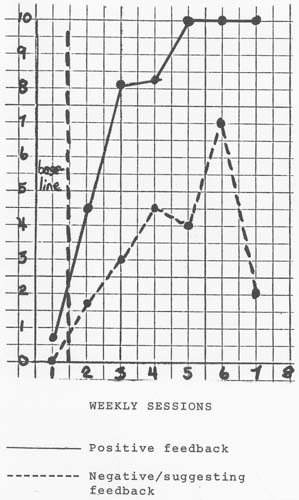

The full data, including pre- and post-testing that were done by the group leaders, are not yet complete. But Figure 1 shows what the women said about their own feelings of satisfaction and anxiety in role plays from session to session. By the third session the women reported clear increases in satisfaction and decreases in anxiety, particularly in the replay after they received praise and suggestions. Tensions went higher and satisfaction dropped in the fourth session when videotape was introduced, but there was a recovery in succeeding sessions. (“There’s always a drop whenever a new element is introduced,” one leader said).

Figure 1: Women’s Subjective Rating of SUDS and Satisfaction

First-time tensions soared in the fifth session as men were introduced, but dropped significantly on the replay. By the sixth session, first-time role-playing tensions and satisfactions had improved measurably and the women reported extremely high satisfaction and very low anxiety on the replay. Training was paying off.

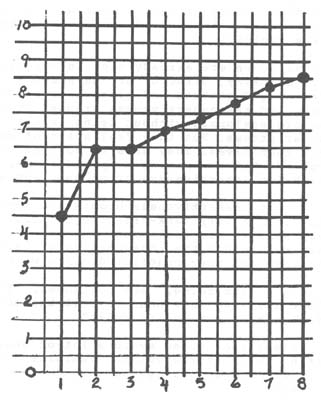

Figure 2 shows how women in an identical assertiveness group conducted in the Fall rated their assertive behavior, on the average. The progress of this group is perhaps more clearly displayed: beginning with an average rating of 4.5, the women doubled their sense of assertive satisfaction in eight sessions.v

Figure 2: Average Rating By Group Members of Their Assertiveness On A Scale of 1 to 10

Figures 3 and 4 show other kinds of progress that can be measured more objectively. Figure 3 shows the average number of positive and negative feedback statements (PARS and NARS) counted by observers for each member in each 50 minute time segment in the Fall workshop. (Negative feedback here includes suggestions). Clearly, the women in this group learned to be bolder and faster in expressing their pleasure and displeasure at what was going on. By the last session negative feedback had dropped off; the women were performing well.

Figure 3: Average Number of Positive and Negative Feedback Statements Made Per Member

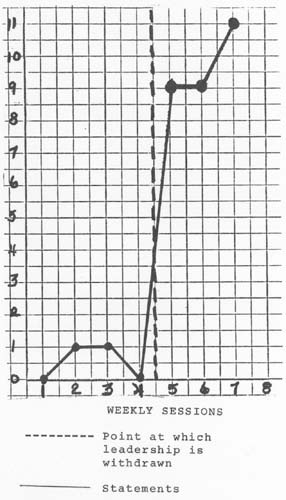

Figure 4 shows what happened in the Fall when leadership was withdrawn and the women had to conduct the sessions without prompting. Direction-giving statements counted by observers (Direct and Indirect Commands) jumped from none or one to nine or 11 in each 50-minute segment. Given opportunity, the women took charge rapidly.

Figure 4: Average Number of Direction-Giving Statements Made Per Member

“Professional women are already high in assertiveness,” said Dr. Barbara Brockway, director of the Wisconsin Behavior Research and Training Institute and supervisor of the social work students who led the assertiveness groups. “They couldn’t become professionals without being assertive. They perform well under stress. But they feel a lot of anxiety when they assert themselves. They have to contend with the whole stereotype of what a woman is supposed to be, and the consequences of being assertive are often very punishing.”

The women in both assertiveness groups now meet monthly as a follow-up. “It’s a very task-oriented consciousness-raising group,” Brockway said. “They talk about the specific situations that occur, they talk about the consequences of being assertive in those situations, and they practice dealing with them.

“I think it’s a good thing,” she continued. “They are a minority, after all, and they need to feel the cohesiveness of the group just like any minority does.”

Couldn’t professional women avoid a lot of heartache just by exploiting their stereotypical “feminine charms” to manipulate people rather than going through the ordeal of confronting them?

“I hate to be melodramatic,” Brockway said, “but in many ways these women are a generation of martyrs. They have broken barriers but they may not go much farther. These people are seeking internal rewards because the external ones may not come. Manipulating people doesn’t make you feel good about yourself. These women have no interest in that. They want to say who they are and what they want, and they want to feel good about it.

“That’s what this training is about.”

©1975 Ron McCrea

Ron McCrea is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin). This article may be Published with credit to Mr. McCrea, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.