Ann Arbor, Mich. — David Lebowitz has a problem. One of his supervisors at the large hospital he manages in New York state is supposed to be interviewing new interns after their first six weeks on the job to tell them how they’re doing. The problem is, the man is not doing the interviews; he is submitting the post-interview checklists without ever seeing the interns. Lebowitz knows this; the supervisor doesn’t know he knows it.

Now Lebowitz is talking with Carol Dunford, a training representative from Maryland National Bank, and Jim Hanley, the personnel director for the Hooker Chemical Co. They are all younger management types, and they are trying to work through David’s problem using the novel techniques of applied behavioral analysis they have been hearing about all morning. It is the second day of a five-day workshop entitled “Managing for Performance Improvement: Principles of Behavior Modification Applied to Work Settings.” The workshop is run by the Graduate School of Business Administration of the University of Michigan, and 20 organizations ranging from Ohio Edison, First National Bank of Chicago, and the Phillips Petroleum Co. to the U.S. Forest Service and the Social Security Administration have paid $495 to enroll their representatives for the week.

Lebowitz scratches his head. It’s a puzzler. “I’d like to get him to improve his performance by telling him he’s doing a good job on the interviews, but if I do that I’m just rewarding his skipping the interviews,” he says. “I could accuse him, but I still wouldn’t know if he’s doing any interviews.”

“You’ve got a faulty feedback loop because your only source of information is the person who isn’t doing the job,” says Hanley.

“What if you have the interns send a separate form to your office after they are interviewed?” suggests Dunford.

“How would I explain that to him?” says Lebowitz. “It would be obvious that I was policing him, and that would be pretty punishing. He’s not a bad guy, he just doesn’t like to do these interviews for some reason.”

“You could just say that you want to get feedback about how these interviews are designed, to improve them, and you could give him just the good comments. You’d have something to reinforce him with” Dunford says.

“And the forms would be a way of making sure the interviews were done,” says Lebowitz. “It’s not a bad idea…but he would have to give them out, and what would stop him from faking them too?”

Dr. Richard Malott, the seminar leader, joins the group and is told what’s going on. Malott, a tall, thin, solemn man of 39 with a long beard, takes in their ideas reflectively.

“Yeah,” he says, “it would be better to build everything into one form, both the checklist and the employee evaluation. Spell it right out on the form: ‘Your supervisor will evaluate your work in several areas during this interview. He will go over the checklist he has made out below. At the conclusion of the interview he should ask you to evaluate the interview. You should write out your comments in the space provided below.’ And make sure the questions are open-ended so the supervisor can’t just fake it by checking boxes. Questions like ‘What did you like most about this interview?’ and ‘What did you like least?’ and ‘How can these interviews be improved?’ It’s always best to build the controls into the system.”

Malott backs up and comments on the situation behaviorally. “Your supervisor must find these interviews pretty aversive,” he says. “It’s hard for some people to tell others they’re not doing so well. Sometimes it’s hard to tell others they’re doing a good job. Anyway, the consequences of doing the interviews are punishing for the guy, while faking the reports gets him out of it without any consequence that’s negative. It’s reinforcing in the short run. It would probably be a good idea, in addition to tightening the consequences, to sit down with the guy and role-play some interviews. Give him some practice, help him feel more relaxed.”

Malott’s prescription involves two behavioral techniques: first, assertive training (role-playing) to solve a skills deficit (not knowing how to tell people good things and bad things without feeling anxious); and second, contingency management to sharpen the results of poor performance (the boss will automatically know if the interviews are faked) and provide Lebowitz with feedback he can then use to reinforce good performance (he can praise the man for something specific).

“This is what behavior modification is always about,” said Malott earlier in the day as we drove to Ann Arbor from his home base at Western Michigan University at Kalamazoo where he is an associate professor of psychology. “It’s about bringing in additional rewards and/or punishers that will shift the balance of consequences for appropriate or inappropriate behavior so that more appropriate and less inappropriate behavior will occur.”

Malott’s approach to the management of businesses and organizations — he prefers to call them “systems” — is a far cry from traditional practices. An ordinary executive might deal with the Case of the Phantom Interviews by confronting Lebowitz’s staff man and chewing him out, or by saving up the evidence and firing him. A behavior analyst would find these solutions wanting. The chewing-out, for example, might work in the short term, but it might also create bad side-effects such as resentment; or the employee might actually increase his chicanery to get more attention from the boss. Firing the supervisor would be a waste of talent since the problem isn’t the man’s evil intent. The better solution, in the behavioral view, is to correct performance by restructuring the work setting — building performance into the job — and by strengthening the worker with training where there appears to be a deficit of know-how.

Behaviorists use recognition, praise, and a regular feedback system to tell the worker how he is doing. They analyze the work situation rather than the individual, and their solutions emphasize manipulating the milieu rather than the actor himself.

Malott begins the day by trying to get his audience of executives to think like behaviorists.

“What does a person have to do to have you call him ‘appreciative?’” he asks.

“Says thanks,” one executive suggests.

“Gives bonuses,” says another.

“Right. Now, what do we mean when we say a person is ‘friendly?’”

“He asks you personal questions.”

“He requests things instead of ordering them.”

“Says hello and smiles.”

“Right,” says Malott. “If someone seems unfriendly, five will get you ten they haven’t learned the behaviors that go into being friendly. How many of you have people in your office who are considered ‘unfriendly’ but you’re really talking about their tone of voice?”

Two hands go up.

“Okay, here’s the point: any human or psychological problem is best thought of as a behavioral problem. Behavior is what you do. Let’s take another word: ‘responsible.’”

“On time.”

“Reliable.”

“By ‘reliable’ you mean a person is able to predict his own behavior accurately,” Malott advises. “Many people are skilled at volunteering but lack follow-up skills. We call them ‘unreliable.’ See, we’re used to thinking of these things as ‘traits’; it’s important to think of them as behaviors. What about ‘pride?’ What does a proud person do?”

“Says good things about himself.”

“Walks in a certain way…”

“Says good things about the company.”

“Okay,” says Malott, “how about ‘loyalty’”?

“Does extra work.”

“Comes in early.”

“Good,” sayd Malott. “The more specific about behavior you are, the more effective you are. Now. What’s ‘professionalism?'”

“Sophistication?”

“What’s that?”

“Using proper English and technical terms.”

“Okay, what else goes into ‘professionalism?’”

“Worrying.”

“Dressing well.”

“Maintaining secrecy.”

“Huh?”

“You know, keeping confidences with clients.”

“Okay, good.”

What Malott is doing is getting these people to be observers. You can’t measure an attitude, and if you’re talking about scientific management you’ve got to have something to measure. So you break down an attitude into the sum of its parts: behaviors. Things you can see and hear and count. Now you’ve got something you can keep track of — and the beginning of a quality control system.

Now Malott is talking about rewards and punishments, the tools of all managers.

“There are two basic kinds of rewards,” he says, “unlearned rewards and learned rewards. Another name for a reward is a reinforcer. An example of an unlearned reinforcer is food. Another is sleep. What would be an example of a learned reinforcer?”

“Getting a thank-you?”

“Right. What’s another?”

“Money.”

“Yes. Do you know why money is a learned reward? Because it is paired with other rewards, some of them unlearned, some learned. What would be an example of an unlearned punishment?”

“Illness?”

“Yes. And a learned punisher?”

“Getting criticized.”

“Good. The point is, if you as managers can give approval to yourselves, your co-workers, and your employees at the right times, you can manage a lot of behavior. You’ve got a lot of rewards and a lot of them don’t cost you much. What are some of the rewards you people have to give, for example?”

“Recognition and awards.”

“Time off.”

“Consulting with an employee.”

“Giving a person authority.”

“Letting people come to meetings like this.”

“Country club memberships…perquisites.”

“The best rewards are those that you can deliver almost immediately when a person performs well,” says Malott. “Give out small doses. You can get a lot more than $100 worth of behavior out of a $100 bonus.”

“What about giving raises?”

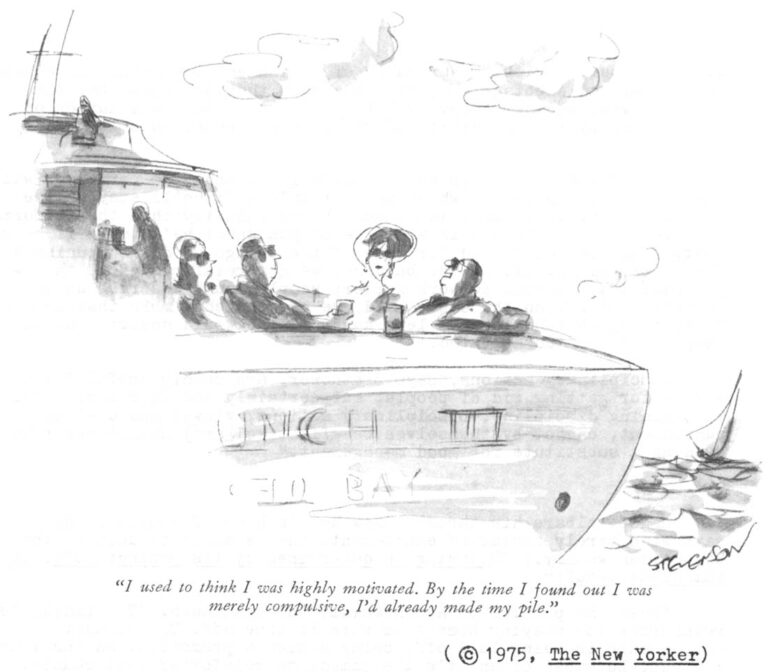

“Right. Dollars are love,” says Malott with a smile. “‘How much do you love me?’ ‘Oh, about $10,000 worth.’”

This is the Behaviorists’ Love Song, and business executives are beginning to see profit in singing along. Behavioral psychology has demonstrated that reward produces high rates of behavior; punishment suppresses it. Researchers say that punishment can stop an undesirable behavior, but that the by-products of punishment are often depression, avoidance, and sabotage against the system that punishes. Dr. Dale N. Brethower, another behavioral business consultant and author of a text used by the University of Michigan workshop, puts it this way:

“Reinforcement increases the probability that the performer will stay in the situation in which he is reinforced; he’ll stay on the job if he can. Punishment increases the probability that the performer will leave the situation in which he is punished; he’ll quit if he can. Most of us are reinforced for some of the things we do and punished for other things. If, on the balance, we get reinforced more than we get punished, we tend to work harder; people would describe us as ‘motivated.’ If, on the other hand, we get punished more than we get reinforced, we tend to work less hard; people would describe us as ‘depressed’ or ‘unmotivated.'”

Disciplinary actions, says Brethower, are mainly useful “as a device for getting rid of people, but certainly not as a device for maintaining discipline. Disciplinary actions, viewed and used as punishment, cannot by themselves be effective [and] should never be used as a substitute for good management.”

Malott clears his throat. “Now here’s kind of a point,” he says with barely contained excitement. (He is about to deliver the Skinnerian whammy). “Behavior is determined by its consequences. By immediate results.”

“Take the problem of absenteeism,” he continues. “The immediate reinforcer for staying home from work is time off. The distant consequence is being laid off, being denied a promotion, having your pay cut. But most often it’s the immediate reinforcer that counts. The same is true with exercise. The road to hell is paved with closets full of unused jogging equipment.”

The executives laugh sympathetically.

“See, it’s what I call the Fallacy of Historic Control. I’m going to say that 80 per cent of our behavior is controlled by immediate consequences; only about 20 per cent is controlled by historic factors. Here’s the overall human dilemma: our behavior is controlled, essentially, by immediate results. And often the immediate results cause us to behave in ways that have disastrous long-range results.

“For instance, smoking cigarettes is a behavior which is controlled by very powerfully reinforcing immediate consequences — the little nicotine rush. The long-range consequences are disastrous. Everybody knows that, but knowing it doesn’t have much effect. So you have to bring immediate consequences to bear that will counteract it, counteract the rewarding consequences of smoking. The same is true of the absentee problem. So industries and organizations are gradually coming to realize that their problems are more often behavior maintenance problems rather than training problems.”

Malott is in a mood to explode myths, so he moves on to the next one — the Fallacy of Resistance to Extinction. (Extinction is the gradual death-by-starvation that happens to any behavior which is ignored).

“Don’t bank on being able to phase maintenance out,” he warns. “You may have to maintain the contingencies for life. If you can fade it, thin out the density of rewards, fine. But the search for the autonomous employee, the self-starter, is somewhat a vain search.”

“Don’t bank on being able to phase maintenance out,” he warns. “You may have to maintain the contingencies for life. If you can fade it, thin out the density of rewards, fine. But the search for the autonomous employee, the self-starter, is somewhat a vain search.”

But isn’t pride in a job well done reward enough for anybody?

“This is another fallacy,” he says. “We say a person ought to want to do a good job. But it doesn’t work that way. People need feedback from other people. Almost always intrinsic rewards are not enough. That’s why we call it work. It’s almost impossible to design a job that’s so fulfilling that you don’t need extrinsic rewards.”

Even a paycheck isn’t much of a motivator, behavior analysts say, because you get the same reward whether you perform well or only marginally. Brethower says that if employees’ wages are the only incentive, “then we should expect the very minimum level of performance, just high enough to avoid being fired. Performance below that level has a very clear consequence: they get fired and do not receive the incentive. But performance above that level has no consequence; they do not get more of the incentive, they do not get more money.” Behaviorists say this is not lazy, it is only the typically efficient way in which humans organize their energies toward results in any setting.

So Malott is urging his seminar students to become behavior boosters.

“One of your major roles as managers is to be feedback mediators for rewards and punishments. It’s tough to do. You often punish people behind their backs and reward people behind their backs. It’s important to get it all out front. In general I recommend structure. I recommend a weekly performance review of maybe ten minutes. It’s good if you can give the positive feedback right away, but too much fast negative feedback has bad side-effects. Save the negative things for the weekly review. I recommend this procedure for marriages, by the way.

“But here’s a big point, one of my rules of behavior modification: nothing in moderation; be consistent! People with performance problems are very good at coming up with reasons for not meeting the criteria. You can always rewrite the criteria. But as soon as you start making exceptions and being reasonable, the situation begins to deteriorate.”

If this sounds ruthless, it is no more so than Malott is with himself. He told me that when he and Donald Whaley, another psychologist, were writing a textbook together they set up strong aversive contingencies (punishing consequences) to keep themselves on deadline.

“We had a weekly assignment and if we didn’t get our assignment done our paycheck for that week was held up by one week. Then I went to daily assignments.”

Didn’t the weekly assignments work out?

“Not as well. You have to make the units as small as possible. Then I even went to hourly assignments whereby I specified that each hour I would write 300 words, then 600 words, and if I failed to do that I would pay a fine of $5 or $1, depending. That’s generally pretty effective.

“Even then the system falls apart sometimes and you have to recycle and redesign it. Whenever you’re implementing behavior systems like that you’ve always got to be on top of ‘em looking at ‘em and be ready to reevaluate and change them, patch them up with a little scotch tape.”

Prospect: A Total Performance Future?

Lectures are fine, but business banks on results. Some early favorable results have come in, and not entirely from the white-collar settings in which one would expect to find behavioral techniques most effective. Safety specialists at the Kroger Co., for example, reported a dramatic drop in back injuries after they adopted a procedure of systematically praising workers when they displayed proper lifting techniques. The annual million-dollar price of insurance premiums, lost time, and training replacements was considerably reduced. And Edward J. Feeney, vice-president of systems performance at Emery Air Freight Corp. was able to save his company $520,000 a year by establishing a feedback system which encouraged packers to use large containers to forward small packages. Feeney’s triumph is the subject of a documentary film, “Business, Behaviorism, and the Bottom Line,” which is now being shown widely in schools. In the film Feeney appears with the father of the modern behavioral movement, B.F. Skinner. Feeney has now started his own behavioral consulting firm, as have a few others. The ground appears to be fertile.

Malott himself organizes his college courses as behavioral systems and has been able to achieve personalized, small-group instruction for one course of 1,000 enrollment by using paraprofessionals and a tight, multi-layered quality control feedback network. The School of Business at Western Michigan University now requires all of its undergraduate majors to take Malott’s introductory behavior modification course.

The behavioral approach seems to offer the possibility of greatly enhanced working lives if it is correctly used. Hierarchies of all kinds are short on praise and long on disorganization and the stupid use of punishment. People are happier when they know what is expected of them and are told how they are progressing. A system which would plug recognition into traditionally “thankless” jobs would be a boon to social morale.

Yet corporate culture already exerts such profound influence on the values and manner of life of all who participate in it that a system which promises nearly perfect management of human behavior takes on an ominous cast. Herbert Marcuse, in One-Dimensional Man, makes the point that “In this society, the productive apparatus tends to become totalitarian to the extent to which it determines not only the socially needed occupations, skills, and attitudes, but also individual needs and aspirations. It thus obliterates the opposition between private and public existence, between individual and social needs. Technology serves to institute new, more effective, and more pleasant forms of social control and social cohesion.” Would a rich schedule of reinforcement purchase corporate efficiency in the short term at the expense of social disorganization in the long term?

Behaviorists in business reject this idea. “There is no more manipulation involved in this than there is in the management task of directing people where to go and what to do,” says E. Daniel Grady, division traffic manager of Michigan Bell Telephone Co. Malott’s own view is this: “Behavior modification is a powerful technology and I know no powerful technology that cannot be used for good or bad, including the written word, the printing press, newspapers, and newspaper reporters. Apologists for behavior modification argue that there’s something intrinsic in it that causes it always to be used for the better. I don’t think that’s true. And again, the attackers of behavior modification say there’s something intrinsic in it that causes it always to be used for the worst, and I don’t think that’s true either. As the technology is now being diffused into receiving systems and user groups, it will tend to reflect the values of the people who are using it, whether those people are school teachers, businesspeople, or whatever.”

One can hope, then, that the managers and organizational leaders who adopt behavioral techniques will use them to humanize work, reduce tedium, and promote excellence. But one can also hope that behavior consultants will broaden their audiences to include not only corporate executives, government officials, and school administrators but also labor unions, citizen groups, and student organizations — user groups that may not manage the systems they work in but have an interest in shaping them nonetheless.

For further reading:

Dale N. Brethower, Behavioral Analysis in Business and Industry: A Total Performance System. Behaviordelia, Inc.(P.O. Box 1044, Kalamazoo, MI 49005), 1972.

Richard Malott, Humanistic Behaviorism and Social Psychology. Behaviordelia, Inc., 1972.

Fred Luthans and Robert Kreitner, Organizational Behavior Modification. Glenview, Ill.: Scott, Foresman & Co., 1975.

Robert Schwitzgebel, “Can We Automate the Good Society?” Interplay, Vol. 3 No. 6 (February, 1970), pp. 28-37.

Received in New York on November 5, 1975.

©1975 Ron McCrea

Ron McCrea is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin). This article may be Published with credit to Mr. McCrea, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.