Mexico City — The psychology of operant conditioning pioneered by the controversial American experimenter B.F. Skinner is spreading through Latin America with the force of a crusade.

Its strongest apostles are young, activist Latins in universities who want to liberate academic psychology from its philosophical past, and educational designers who want to use the technology of behavior modification to transform the social landscape of their countries.

Much like the situation in the United States ten years ago, the Latin behavioral movement is mainly a campus phenomenon and the largest practical adaptations of theory are to be found in instructional technology. Behavior modification has not yet been adapted for the kinds of social control purposes which have made it controversial in the U.S. — possibly because Latin regimes have little need for subtle tools. There is ideological debate over behavior modification on the campuses, but interestingly many of the most ardent Skinnerians are to be found on the Left.

The younger behaviorists are loyal to the Third World and highly sensitive to any move which suggests direction or co-optation by institutions in the United States. But prominent U.S. scientists are widely involved in the activities of the Latin movement, lending advice as well as giving credibility and security to their Latin colleagues’ work. In November and December of last year, for example, both Skinner and his longtime associate Fred S. Keller were brought to Mexico as honorary chairmen of behavioral conferences in Mexico City and Xalapa, Veracruz. Both men received the kind of press and public attention accorded culture heroes.

The Mexican behavioral movement is really two-pronged, with one stream of energy coming from younger, more independent and research-oriented psychologists at university campuses, and another coming from generally older but equally committed educational psychologists promoting the Keller Plan.

The Keller Plan, also known as the Personalized System of Instruction or PSI (SIP in Spanish), is a teaching method grounded in reinforcement theory. In ten years it has achieved immense popularity in Mexico. The key components of a Keller Plan course are small units of study paired with carefully specified study objectives; the use of proctors to give students face-to-face feedback and guidance on their performance; the reduction of professorial lecturing to an “inspirational” role; and, perhaps most importantly, self-pacing by the students through their units of study.

In a PSI-designed course each student studies carefully programmed units of material and offers himself for testing when he feels ready. If his performance falls short of perfection (which is the only criterion), he receives immediate remedial help on the unit from his proctor and gets another chance at the test. He may not progress as quickly as other students, but this carries no penalty and when he does progress it is with mastery. The system seeks to allow for individual differences and build a string of successes for every student. It aims to avoid the usual educational trap in which a few skilled students learn and are rewarded while the rest fall behind, receive no help, and are increasingly punished by the system until they drop out.

PSI is based on the operant conditioning theory that behavior which is reinforced, including study behavior, will increase in frequency while behavior which is punished will decrease and also become escapist and possibly hostile. According to Keller, “the designers of the system had the goal of maximizing rewards for educational behavior, minimizing chances for extinction (dropping out) and frustration, eliminating punishment and fear, and facilitating the development of precise discriminations.”

Fred Keller is one of American behavioral psychology’s grand old men. He and Skinner both pioneered in the field. They share an association that stretches back to their graduate days at Harvard in the ‘30s, and each man has dedicated books to the other. For many years Keller was chairman of the psychology department at Columbia University. Today, at 77, he devotes his time to PSI at the recently formed Center for Personalized Instruction at Georgetown University. Keller is wiry and vigorous, with snow-white hair, wide blue eyes, a sparkling wit, and the kind of permeating kindness that comes from decades of caring contact with students.

Keller established North American behaviorism’s first ties with Latin America in 1961 when a former student arranged for him to teach at the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, as a Fulbright-Hayes Professor. PSI was not hatched until three years later when Keller and three associates were asked to organize an ultra-modern psychology department using the latest techniques of instruction at the University of Brasilia. The associates, still active in the behavioral movement, were Carolina Martuscelli Bori and Rodolpho Azzi of the University of Sao Paulo; and J. Gilmour Sherman, a colleague of Keller’s at Columbia who had also received a Fulbright grant to teach at Sao Paulo.

The PSI squad made a tour of United States behavioral centers, interviewing luminaries and taking notes. They were especially impressed with the teaching methods used by Skinner in his natural science course at Harvard, and by Skinner’s associate Charles Ferster, who was holding courses in behavioral technology at the Institute for Behavioral Research, a think-tank outside Washington, D.C. (Ferster himself later became the first person to introduce PSI methods to Mexico). The four psychologists regrouped in front of Keller’s fireplace in Englewood, N.J., in March of 1963 and laid out the blueprint for PSI in one night.

There was a brief delay due to political turmoil in Brazil, but finally the system was planted at Brasilia and took seed. Its growth was boosted substantially in 1972 when UNESCO financed a training workshop for 40 teachers from 12 Latin countries. Sherman, who conducted the workshop with Bori, says those teachers have multiplied the numbers of PSI-trained instructors considerably by holding their own workshops. The PSI center at Georgetown keeps all of these teachers in touch with one another and current with the latest refinements in PSI through a regular newsletter.

Today, Sherman says, the Keller Plan is used to teach “hundreds if not thousands of courses, putting them all together. There are a few courses in Chile and a few in the Argentine, but mainly in Mexico, Brazil, and Venezuela.”

According to Sherman, “there seem to be some attributes of PSI that each country finds useful to solve its own particular-problems. In Brazil, PSI is primarily being used in technical schools. There are hundreds of these federal institutes all over the country and PSI has more or less been officially adopted as the teaching mode.

“In Venezuela they have a center and I think they are doing more research than other countries. In Mexico the biggest concentration is at the University of Monterey, which is a huge university. There are probably more PSI courses at that campus than at any other single campus in the world.

“They’re doing a thing that is kind of interesting. They’re setting it up so that every student must take one PSI course. From then on he can choose regular lecture courses or PSI courses as he wishes, but he has to have one so he can make an enlightened choice.” Sherman, who directs the Georgetown center, said he thought it would be a year or two before the Monterey students’ verdict was in.

Behaviorists say their teaching systems may not cost less, but because students tend to learn more when they are used, behavioral education is more cost-effective.

The Campus Movement: “It’s the Chinese Technique…”

The campus-based Skinnerian movement in Latin America has had a more colorful history than PSI, and it may be the more significant of the two since its origins and present leadership are completely indigenous. The campus Skinnerians, though most are in their 20s or early 30s, are already seasoned power brokers who hold a long-term vision of their role in national development.

Emilio Ribes, at 31 one of the “oldest” of the founding fathers of the Mexican movement, has been teaching, experimenting, and organizing behaviorists for nearly ten years. He is a dark, bearded, charismatic man with piercing eyes and an ironic wit. His manner is at once low-key and high-intensity.

While visiting a conference on behavioral technology in higher education at the University of Veracruz at Xalapa — the campus where the movement was born — Ribes took time to assess the position of Mexican behaviorism.

“There are at least three schools of psychology that are called behavioral,” he said, “Xalapa, San Luis Potosi, and Iztacala (a new branch campus of the Mexican National University in Mexico City). The south campus of the National University has a lot of people, Nuevo Leon has a lot of behavioral people now, and it’s beginning to spread like…like a disease! Even the scholastic schools have to have a course on behavior modification. Even if they don’t agree, they have one course. They have to have it.”

Ribes is about to do some major empire-building at Iztacala, where he has taken charge of a newly-formed psychology department. “We’re going to have 3,000 students taking just psychology, nothing else,” he said. (Students in Mexican colleges, or licenciaturas, specialize in one subject for four or five years). “So when you have 3,000 guys, you don’t have to worry too much about what’s going to happen. In a centralist country like this, what happens in Mexico City, if it’s definite, is going to happen sooner or later in the rest of the country.”

Three thousand behavior modifiers?

“Yes, nothing else. It’s the Chinese technique. We’re just going to flood the country with people.”

There will be no deviation in Ribes’s faculty. “I am just choosing very young people, operant people and intelligent,” he said. “I don’t care if they don’t know nothing; they are going to learn it. It will be a good training example for the students: even the teachers are going to learn it.

In addition to Ribes’s department at Iztacala, another new campus of the National University, this one in the city of Saragossa, is also being consolidated along Skinnerian lines by his friend Carlos Fernandez, the chairman there. “That means a school of 1,500 students,” he said.

“A Kind of Machiavellian Project…”

Like many social movements, the behavioral movement in Mexico had its origins in a small group of frustrated but adventurous young people. Ribes was one of them. He tells the story this way:

“We were trained in the National University in 1960 when it was a very psychoanalytic department. We learned from people in neurophysiology that there was an experimental psychology and we were quite interested in it. We were always fighting against the department chairman, who was a philosopher, asking for a more objective kind of psychology, more labs and all that. We never succeeded and we weren’t learning anything. We were really concerned about it because we had to find jobs afterwards and we weren’t learning anything useful.

“There was an opening at the Xalapa behavior clinic in 1960 and one of our group was appointed because he happened to be at a cocktail party and met the secretary of the university. A few months later two of us joined him. There were a lot of mathematicians and physicists at Xalapa and we felt we had more in common with them than with other people. So we planned a kind of Machiavellian project and we founded a School of Sciences where psychology was included in the sciences for the first time in Mexico.

“We designed a new curriculum that stressed experimental psychology. None of us knew anything about experimental psychology but we learned along with it. We said, ‘Well, the first experimental psychologist made it by himself and he had to write it up too. We already have it written for us, so it should be easier!’ So we decided to make it by ourselves and there were three or four years when we really learned a lot by teaching.”

“In 1966 we invited O.H. Mowrer (an American learning theorist) to come to Xalapa for a lecture, and he accepted. He then invited us to come to Champaign, Ill., to visit him. A group of us went — I didn’t go that time — and Mowrer introduced them to Sidney Bijou (a leading figure in behavioral psychology).

“Bijou urged them to visit Nate Azrin’s lab at Anna State Hospital

(also in Champaign), so they went to see Azrin and Ted Ayllon was there.” (Nathan Azrin and Teodoro Ayllon are also prominent Skinnerians. They conceived the “token economy” now widely used for behavior shaping in U.S. schools, mental institutions, and juvenile homes).

“So we invited Ted Ayllon to come in February of 1967 and Bijou stopped in Xalapa during his vacation in Veracruz. After their visits people began to read and became fond of the applied perspective that operant conditioning had. So one of us, Florente Lopez, began the first behavior modification program. He founded the Center for Training in Special Education. He began with five retarded children that the special education school of the university didn’t want because they weren’t progressing.”

Meanwhile Ribes went to Toronto for his master’s degree. On his way, he had a bitter revelation.

“I stopped in Champaign to visit Bijou. My wife Sylvia and I stayed for three days. At that time I was not very operant. I knew about operant conditioning, but we all had the prejudices that people have against Skinner — you know, ‘They are interesting people but they are very limited.’ One day I told Sylvia, ‘I am going to tease Bijou. I want to know what he says about certain problems that I am sure Skinnerians cannot answer.’ So I began teasing…and Bijou began answering! That night I told Sylvia, ‘How stupid can a person be for so many years? What have I been doing?'”

“It was a very frustrating thing because I realized I was on my way to study for a master’s degree in something I wasn’t interested in. It was a cave of cognitive people in Toronto, statistical people. I really know what aversive control is!” By the time Ribes got back to Xalapa in 1968, 70 per cent of the department was Skinnerian.

“There were two groups in Xalapa. There was the conservative group that said, ‘Yes, we know a lot from reading but we shouldn’t begin anything applied because we have not been trained.’ We called them the British Group. We called ourselves the Chinese Group. We said, ‘When Bijou began working with retarded children no one trained him; he just began, and so we have to begin.’ And we began and we did a lot of stupid things and we learned a lot. That’s the way, you know, things begin growing.”

“Skinner? Who’s Skinner?”

By 1967 the Xalapa campus had “got religion” and was ready to proselytize. The Xalapa behaviorists organized the first Mexican Congress on Behavior Analysis and invited students and psychologists from around the country to attend. Ribes remembers it with amusement:

“People came from Mexico City to Xalapa saying they were ‘going to the ranch.’ We began just shutting them down, saying they didn’t know anything about psychology. We were like the angry children who shout, ‘We are here and we know more than you, Daddy!’ They were very shocked. Many people had never heard of Skinner. ‘Skinner? Who’s Skinner?’ So they began worrying about who Skinner was, what operant conditioning was about, and they began changing things.

“A lot of new students were interested, too, and many moved from Mexico City +o Xalapa. We began a program here in behavior modification. People like Bijou and Ayllon came to help us set it up, and we got assistance from others in Colombia and Brazil. Things began growing. Some people from Xalapa moved to the National University and consolidated more things there. And then students from Xalapa moved to other universities and that spread it everywhere. So Xalapa was a model.”

Cultural Imperialism from Kansas?

By 1974, behavioral centers in the United States were aware that something was cooking south of the border. The pace of international exchange had quickened. Professors were flying south and students were flying north to attend the Skinnerian schools of psychology — principally the University of Kansas and Western Michigan University. But the Mexicans were not prepared for the news that Kansas was planning to begin a Latin American journal of behavior analysis.

“We had thought of beginning a journal, but not just then,” Ribes recalls. “We found the idea insulting. I mean, they could do a Midwest journal of behavior analysis or an Out-West journal — I don’t know where Kansas is — but why do they have to do it for Latin America?

“The idea was to make the journal to ‘shape’ people. ‘Shaping’ is sometimes a pejorative thing. It means, ‘We know there are going to be high-quality papers, but you have to learn how to do them. So we’ll help you.’ Half the articles were going to be Spanish translations of articles from JABA and the other half were going to be articles by Latin Americans who were going to be taught how to write something decent.” (JABA, the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, is the preeminent journal of behavior modification. It is edited at Kansas).

The Mexicans acted immediately. They announced the formation of their own journal and at the same time sent word to Kansas that their competition would be considered offensive. “They just stopped,” Ribes recalled. “I think they’re doing a newsletter or something.” The Latins’ journal has just published its second edition with a distribution of 3,000 copies . Ribes is general editor.

“It is designed with the idea that not now, but in 20 years, the Spanish language is going to be important in behavior analysis,” he said. The journal is edited by a group of psychologists from several universities.

“I think the outcomes will be seen in five or six years,” Ribes said, “but it’s a good journal. It has standards. People are learning to write for it but not by shaping. We set the same standards that you have: you do a lousy paper and you get it rejected and you learn how to write it correctly. By not reinforcing bad writing you are going to get good writing.”

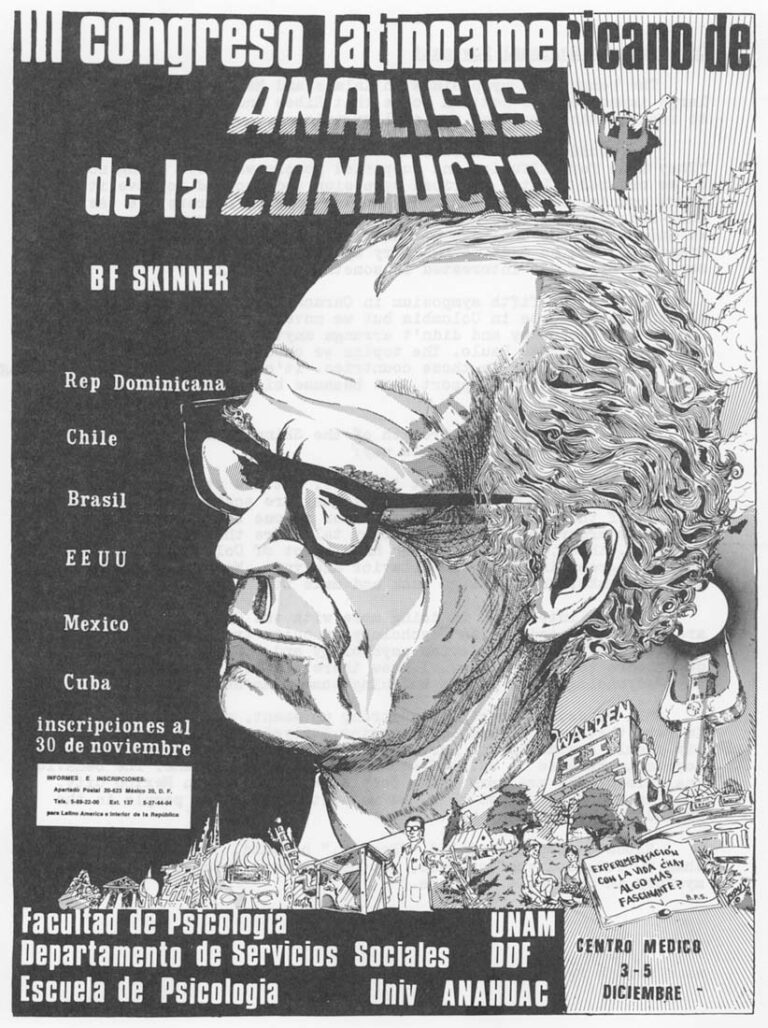

THE CONVENTION POSTER of the Third Latin American Congress on Behavior Analysis, shown at right, dramatizes the cult of personality which has grown up around B.F. Skinner in Latin psychology. Skinner was the honorary chairman of the Mexico City conference held in December, 1975. In the poster the countenance of Skinner looms over a tableau which includes the Greek columns of the academy; a human head cut away to reveal what appears to be solid-state circuitry; a rat pressing a lever in a Skinner Box and awaiting reinforcement from an experimenter who holds the controls in one hand while pointing to the future with the other. The future is a mixture of bucolia and science fiction — Walden Two. At the summit there is a temple in the shape of a psi, the symbol for psychology, with the letters E:R emblazoned upon it to signify “stimulus-response” (estimulo-respuesta). A flock of birds ascends in the sky. They appear to be doves but they are undoubtedly pigeons, Skinner’s famous experimental animals. The convention insignia, a pigeon perched on the map of Latin America with a psi superimposed on it, is reproduced over Skinner’s head. At the lower right, a book is opened to reveal some Skinnerian scripture: “Experimentation with life: is there anything more fascinating?” The countries listed at left were the countries that sent speakers. (EEUU is the United States. The Cubans never arrived). Students and professors from many Latin countries not listed also attended. There were nearly 2,000 of them.

Organizing a Regional Movement

The behavioral symposiums in Xalapa and Mexico City had such a large impact on the Mexican scene that Ribes and his group decided to use the same tool for regional organizing.

“We decided that these symposiums were important,” he said. “They made for diffusion and supported people who were doing something. So we created a Latin American symposium and decided to move it to every country in Latin America that was growing a group. We set a full schedule and we organized a Latin American steering committee. We made Bijou the chairman of the first one. He had quality decision standards, and he made things very apolitical besides. No one could say that Bijou was interested in something special.

“We had the fifth symposium in Caracas last year, and this year we were going to be in Colombia but we moved it to Panama because they didn’t give us money and didn’t arrange anything. We plan to have the next one in Sao Paulo. The topics we choose are topics that are important for people in those countries. It’s a supportive kind of thing. They can get a lot of support just because big people come and talk about it.”

Asked to assess the strength of the Skinnerian movement outside Mexico, Ribes summed it up this way:

“It was growing very fast in Chile, but now it’s decreasing very fast. Brazil has a big movement, but they are scattered. They are not joined. If they could just get together in one big group they could make some progress. In Colombia they talk more than they do. They have two, three, four people. We have a lot of Colombian students taking degrees in Mexico in behavior analysis. We have about eight or nine students. They will go back and make it.”

“We are interested in doing more with the Cubans because they are quite isolated. Cuban psychology is quite traditional still. It’s a mixture of Soviet Pavlovian psychology and other psychologies. They don’t care too much anyhow. I know there are more important things than psychology when you’re building something new.”

“In Venezuela they have a strong movement, and Panama is strong. In Peru they have a Peruvian Behavior Analysis Society, with five or six people beginning it. Peru was a very traditional country psychologically because it was influenced by the Argentinians. The behavior analysis people are very young people. We met them in Mexico City. They came and we helped them and we sent them to see people in the United States and they went back.”

Ribes paused and smiled. “Really,” he said, “if you have more than 90 I.Q. and you can read, you can do good things. There’s no mystery in the whole business.”

Received in New York on February 6, 1976.

©1976 Ron McCrea

Ron McCrea is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin). This article may be Published with credit to Mr. McCrea, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.