In the January 1972 issue of Harper’s, I wrote an article called Soul In Suburbia, in which I tried to show that it was futile for the black middle class to think that it could escape from the problems of underclass blacks. I stressed that as long as a floating, black, poverty-stricken class existed, there would be no security for blacks in this country, because their problems here remained, fundamentally, political ones to be exploited at any time, by any politician of sufficient rightist charisma. I argued, further, that middle-class blacks had been seduced by the myth of individualism and had come not only to enjoy their seduction, but to believe that their salvation lay in Individual conquests of poverty. All these notions, I said, tended to make some middle class blacks wary of offering a helping hand to the despairing poor of the urban ghettoes. And I ended the piece by saying that there could be no relaxation for the black middle class, no false lull in the struggle for selfhood, as long as the underclass black gazed at the world from a garbage can.

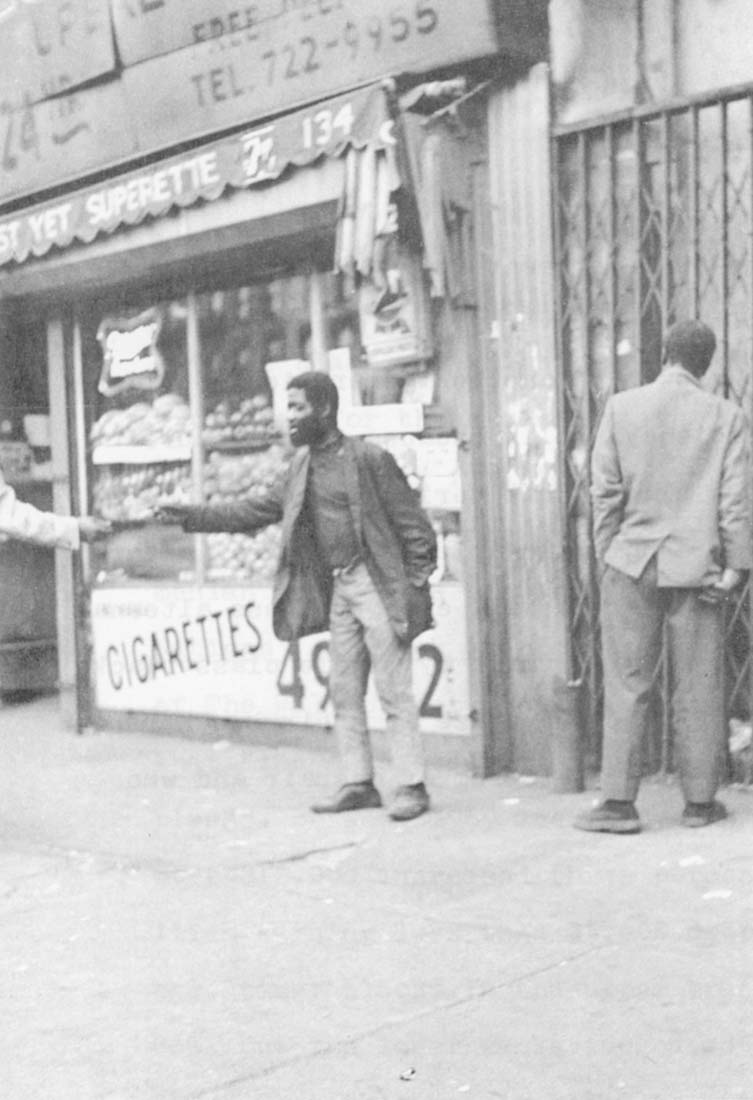

I see, now, that I may have done the black middle class an injustice. For what is apparent in my conversations around the country, is that the black middle class is not retreating from its responsibility to help poorer blacks, but that it is afraid of the chaotic black underclass as are most white peoples For there exists in America today, three broadly defined black groups: (a) The black middle class: An amorphous group whose members may earn from $12,000 – $100,000 per year. (b) The black working class, which consists of a rural farm proletariat that is barely self-sufficient or a hardworking, urban proletariat whose lack of education and skills dooms it to live in the ghettoes. (c) The black underclass: A strictly urban phenomenon consisting of a band of men and women whose hopes are of the moment, and who exist in a whirligig of poverty, welfare and crime from which there seems to be no escape.

A black middle class – through luck, fortitude, sacrifice and discipline – has been around since the generation after the Civil War. But its position in American society has, until recently, remained rather precarious. In 1959, James Baldwin went to Atlanta to look at the city that reputedly had the largest number of middle class blacks. In a piece called Nobody Knows My Name: A Letter from the South that appeared In the Winter, 1959 issue of Partisan Review, he wrote that the wealthy blacks of that city were in “a really quite sinister position.” He buttressed his argument by noting that:

Though [the blacks] and the mayor are devoted to keeping the peace, their aims and his are not, and cannot beg the same. Many of those lawyers are working day and night on test cases which the mayor is doing his best to keep out of courts The teachers spend their working day attempting to destroy In their students – and it is not too much to say, in themselves – those habits of inferiority which form one of the principal cornerstones of segregation as it is practiced in the South…. They are in the extraordinary position of being compelled to work for the destruction of all they have bought so dearly – their homes, their comfort, the safety of their children. But the safety of their children is merely comparative; it is all that their comparative strength as a class has bought them so far; and they are not safe, really, as long as the bulk of Atlanta’s Negroes live in such darkness. On any night, in that other part of town, a policeman may beat up, one Negro too many, or some Negro or some white man may simply go berserk. This is all it takes to drive so delicately balanced a city mad. And the island on which these Negroes have built their handsome houses will simply disappear.

Well In the 15 years since that piece was written, some of Atlanta’s blacks have prospered beyond their wildest imagination. Their showpiece homes are now Included In bus tours of the city, and it comes as some surprise to hear old white bus drivers extolling, in Dixie accents, the loveliness of the homes of “our magnificent black citizens.” Of greater importance, naturally, is that the present mayor, Maynard Jackson is black, and that the only national political star from Georgia is black, middle class Julian Bond who lives in Atlanta.

Much has changed in the lives of the black middle class in the last decade. In fact they have radically altered their lot; they have been the prime recipients of the gains of the civil rights movement and they have begun to speak with more than a modicum of self-assurance, with the distinct feeling that they count in American society and that, soon, they too will become power brokers In a land that once despised them. But I have found that concomitant with these positive feelings, there is among many members of the black middle class, a general uneasiness about their Inability to change the lot of the black underclass, and a morbid fear of that this class hates them, and views them with as much animosity as it does whites. The result of this has been both a physical retreat from the black underclass, and a psychological retreat that has at its base the realization that there is very little one can personally do to change the tide of disaster that is washing away young black lives every day.

A young, black teacher from Charlottesville, Virginia tells a visitor, “I have become absolutely terrified of my own people and in consequence have planned a lifestyle that has taken me as far away from congregations of them as possible. Of this I am not proud.” And a 36 year old mother of three who lived In Harlem by choice, until her public relations husband, fearing for his family’s safety moved them to Montclair, sits in her spotless kitchen and tells this writer: “It got so bad that whenever I saw two or three black boys walking toward me, my heart would begin to beat quickly and I would cross immediately to the other side of the streets As soon as it got dark, I developed X ray eyes. My boys will soon be 14 and 15, and I wondered how many other black women crossed the street when they approached.”

Peter Bailey, an associate editor of Ebony who lives in Harlem because of his commitment to its people, and who is tireless in his community efforts, tells of getting on the elevator in his building and noticing a 12-year-old black girl in the corner. As soon as it became apparent that only both of them would be in the elevator as it ascended, the girl’s eyes bulged as she looked at him, and she “escaped” through the closing doors. She had been taught never to ride in elevators alone with black men, and Bailey, a gentle man, was devastated when he realized that in the eyes of that young girl, only his blackness mattered, and that although she was black, she had learned through experience that her own skin was a threat to her safety.

Still many middle class blacks are trying to do what they can to change the plateau of despair in the ghettoes. They have their work cut out for them. A doctor from Los Angeles who lives In the fashionable, black section called Baldwin Hills, and who is always, quietly, starting projects in Watts says: “I try and I try. But I am constantly ripped off. They think I’m a chump for helping and because they can’t even begin to see any value in themselves, they can’t see any in me, But we – the lucky ones have to continue to help even at the risk of bodily harm, because things can’t get much worse and then they are bound to get better.”

Not many members of the black working class take so sanguine a view of the people they are forced to live among. Since they lack education and skills, they cannot easily leave the ghetto, and their earning power is being whittled away by inflation and taxes. They must live with the knowledge that on some crowded or deserted street, near to their homes, they will be attacked by the muggers and junkies who are their neighbors. They know that sooner or later they will return to their homes and find their meager possessions of a lifetime gone.

They are understandably bitter, and, unorganized, they have begun to fight against the criminals in their midst. A young shipping clerk, Carl Malloy, was robbed at knifepoint of a ring and $5 by two thugs at 155th street and St. Nicholas Avenue in New York. Furious he rushed home, borrowed a gun from a neighbor who offered his cart and together they went looking through the streets of Harlem for his assailants. They found them, drinking wine and laughing at 145th street and St. Nicholas Avenue. Malloy dashed out of the cart took all the money they had, tore it up, and with his neighbor holding the gun on the thugs, he beat them to a pulp. Later in the summer as he recalls the story, he would says, “This shit has got to stop. I work everyday for whatever little I have, and I’ll go to hell before I’ll let every mugger walk over me.”

And in Brooklyn, a taxi driver who lives on Quincy street in the Bedford Stuyvesant section of that borough, and who can barely support his wife and four children, sits in front of his television set drinking Budweiser and telling a visitor of the rage that follows him through the streets of his community:

“I thought if you gave people a chance they would help themselves. But these people don’t want to. They want what you have. Nobody gave me a dime in life. It was ten of us and my father tried his best with his farm In Alabama. He died from overwork. And here I am trying so that my children can go to college, maybe, and we’re like suckers for these muggers. They’ve robbed us at home twice. I’ve been held up in the cab twice. My wife was mugged once. No more Mr. Nice Guy with me, I have a gun in the cab, one at home and my wife has one. They are not legal, but shit, man, all I’m doing is giving my family a fighting chance. The mothers wont get us so easy now. They’re going to have to expect some lead.”

It Is because of the cycle of welfare, crime, drugs and poverty among the black underclass that the black middle class sees a cloud on its horizon. For its future can never be limned with greatness if it continues to be afraid – justifiably so – of members of its own race. There is no question that discrimination and segregation ravaged the psyches of many blacks, and that even if, today, the opportunity to be whatever one wanted in this country beckoned, many blacks would be unable to take that first step toward their pot of gold. So blaming the past cannot help the future although it may make the black middle class more understanding when it sees that In the eyes of the black underclass it has become a potential enemy.

In July, the Census Bureau revealed that the income gap between black and white Americans that had been narrowing up until 1969, had for three consecutive years begun to widen. The median income for black families was in 1973, 58% of the median for white families. Or to state it more graphically, black versus white median income was back to the 1966 level. In an article The ‘Two Nations’ of Black America that appeared In the September 19 Issue of The Wall Street Journal, writer James Ring Adams pointed out that “income distribution is growing more and more unequal among blacks. Between 1969 and 1973, the proportion of whites earning over $12,000 increased three percentage points to 53%. White families earning less than $5,000 dropped one point to 13%. At the same time, blacks in the upper bracket increased three points, to 26%. But the lower ranks increased by two percentage points to 34%.” What this really meant as Adams noted, was that “the black rich are getting richer. The black poor may not be getting poorer, but their numbers are increasing. As a result, income distribution among blacks alone is far more unequal than Income distribution among whites.”

The black middle class sees what is happening and does not like it, but there is little that this class can do since it is still mainly a wage earning professional class, and what industry it owns can be passed through a camel’s eye. “Government action is the only solution,” says a civil rights lawyer In Washington, but he doesn’t know what kind of government action he should propose. Welfare programs have not ended poverty, and they have, if anything, contributed to the growth of another generation of blacks who are lacking in self-sufficiency. It is because this posture is becoming endemic among some blacks that serious attention must now be paid to some heretofore-unmentionable governmental alternatives. In a subsequent newsletter, I will explore these alternatives and. the responses and suggestions made by middle class blacks as, from their comfortable bastions, they gaze at their brothers who have been caught in an unending maelstrom of despair and who they achingly want to help.

Received in New York on September 30, 1974.

©1974 Orde Coombs

Orde Coombs, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Coombs and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.