The end came suddenly so that although Rosa Victoria Jones Holloman had been ailing for over three years. It was something of a shook to learn that she had died. She had gotten frail and time had finally withered her. But although she remained bedridden for the last years of her life, there was still a gleam in her eyes as she watched you and as she silently let you know that she was still the matriarch to a family of achievers.

The last six months of her life had seen her have her moments of despair, for she realized that she was the last surviving child of Robert Shelton Jones, the slave who after Emancipation had walked home from Tallahassee, Florida to Albemarle county, Virginia to start a family; and it bothered her, for she would whisper: “I’m the last to go. I don’t like it one bit.” It troubled her that she could no longer attend the Sunday church services at the Second Baptist Church In Washington, D.C., where her husband had been a pastor for fifty-three years. At first she had Insisted on going to the services even though she had grown infirm, and when she could no longer climb the steps of the church, she would have one of her daughters sit with her In a car outside of the church so that she could savor the church’s ambiance and receive the good wishes of the parishioners. But all that had had to stop, and she was obliged to spend most of her days in bed.

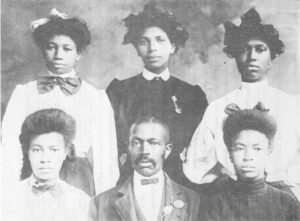

From a distance of five generations: | |

| Margaret Jones The old and blind mother of Robert Shelton Jones who was born a slave about 1820, and who took care of Rosa Jones Holloman and her sisters after their mother died in 1894. |

| In 1947, her great, great grandsons pose with an Easter Bunny on the streets of Washington, D.C. (Left, Jason, Right, Danny Parker). |

Two weeks before she died she had told a visitor to ask her grandchildren who lived some distance away to come to see her, and she had held this visitor’s hand a little longer and a little more tightly than usual. Now, on March 19, 1975, this visitor is attending her funeral services and hearing her eulogized as a “good and gracious woman.” But because she had lived such a long and productive life, there seemed to be little cause for overt grief. As her grandson, Barrington Daniels Parker, Jr. noted: “If you look at her life you will find some reason for celebration. The distance she traveled from her birth, as the daughter of a slave, to her death as the head of a functioning, tightly knit family unit is sufficient justification for us to eschew mourning. With her death, an era ends and that, of course, makes us sad.” Parker is a corporation lawyer In New York, and at 30, he will be arguing his first case before the Supreme Court In the fall.

His brother, Jason, a doctoral candidate In Chinese studies at Princeton University observed on the day his grandmother was buried: “With the exception of our cousins Edward and Fanny Brown In Profitt, Virginia (See newsletter 4) there are no surviving members of our family who grew up close to the earth. In some vague and undefined way, that bothers me a bit, for we are now a totally urban family.”

The funeral services for Rosa Holloman were simple and moving. It was as if her illustrious family wanted to stay on the sidelines, and let the parishioners of the church in which she had worshipped for 58 years claim her and thank her, in death, for having walked among them. And so while the Washington rain poured that chilly Wednesday March morning; while the dignitaries of the city scrambled from their limousines and into the warmth of the church; while all around the Second Baptist church one saw media faces, only those who had known “Mother Holloman” for a long time rose to eulogize her. Just before the formal eulogy was delivered by The Rev. Dr. John Malcus Ellison, the Chancellor Emeritus of Virginia Union University, and a man who had known the Hollomans for nearly 40 years, a young member of the congregation got up and rather nervously read the following statement:

Sorrow tugs at us. We want to mourn, not so much for her passing, but for the space that her passing leaves in our lives. But maybe instead of tasting bitter sorrow, we ought to rejoice in the wonder of her life. She was born black and poor in a country so teeming with racism, that it would not then recognize her moral weight. But no venom ever spouted from her lips, no despair ever shadowed her eyes; no malice ever touched her heart. So that by the time she died, she had given us all that she had to give and that was the proper measure of herself. And are we not all broader, fuller human beings for Mama Holloman’s 86 years passage on this earth? Are we not nobler because she touched us or smiled at us, or loved us gently without expectation or hope? So as we gather around co gaze at our loss, maybe we should also look at this generous woman’s life as a wonderful oasis in the terrible Sahara that surrounds us. This is and will always be the legacy that she leaves us. And what a legacy it is: What a light to guide us through all of our shadowed, despairing tomorrows!

Soon it was over and the cortege made off in the downpour for the Lincoln Memorial Cemetery. In the mid-afternoon a wake was held at the home of Judge and Mrs. Barrington Parker In Northwest Washington. Ms. Parker is the daughter of Rosa Holloman and at 57 has recently retired as chairperson of the Department of Education and Psychology at the D.C. Teachers College. Dr. Marjorie Parker had also been a D.C. city councilwoman since 1972 when then President Nixon nominated her to the nine-member council. After the home rule referendum was adopted in May 1974, Dr. Parker decided not to run for elective office. Her husband as a U.S. District Court Judge was prohibited by a code of ethics from taking part in partisan politics, and because so many people were urging her to run for elective office, her husband felt it necessary to write to a special advisory committee on judicial ethics about the propriety of having her run for the city council. When she decided not to run, theme was an audible sigh of relief from the advisory committee. In fact, last February, Senior Judge Albert Tuttle of the U.S. District Court in Atlanta, who would have had to advise Judge Parker, was moved to state that Marjorie Parker’s decision “simplifies the matter for us considerably.” And indeed it did, for Marjorie Parker takes a back seat to no one, and my guess is that if they had ruled against her she would have fought the case all the way to the Supreme Court. With the load of women’s rights grievances cases now before the courts of this country, Ms. Parker would hardly have accepted an adverse decision calmly.

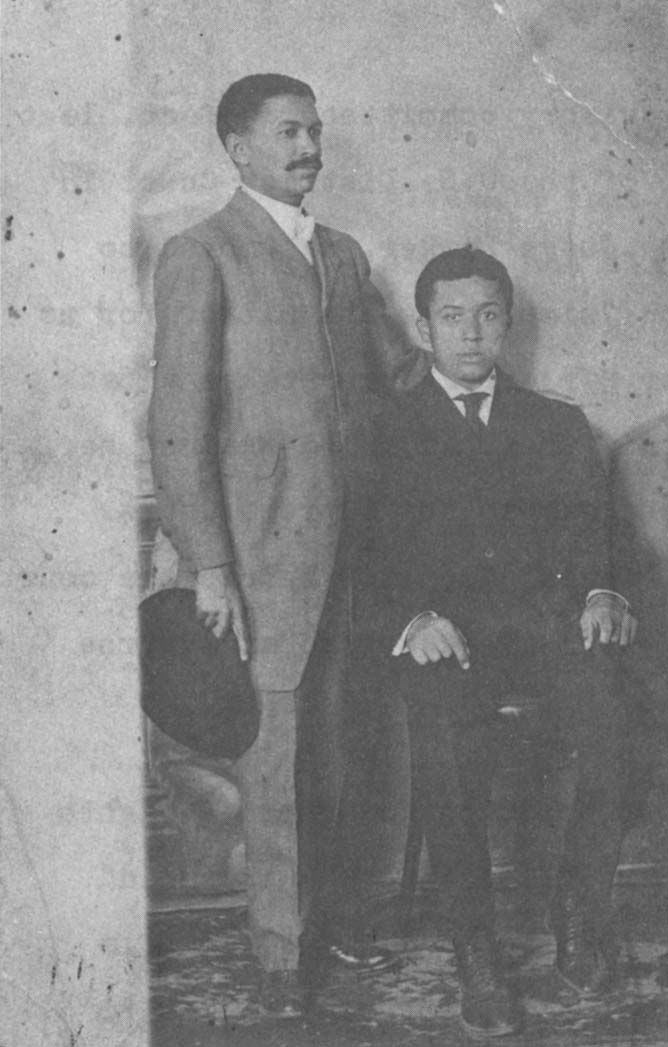

At any rates such questions about politics and women’s rights were kept In the background as mourners filed into the splendid home of the Parkers to talk about Rosa Holloman and the end of a generation, But the talk about Rosa Holloman kept coming back to the man she had married on June 12, 1912, and who had died in 1970. His name was John Lawrence Sullivan Holloman who, as the oldest of ten children, took over when his father died. They owned a small farm and John L.S. Holloman began to preach on Sundays and farm during the week. From being a pastor of several “one-Sunday a month” churches, he progressed to being the full-time pastor of Second Baptist Church in 1917. He received a doctor of divinity degree from Virginia Union University in 1937 and became president of the Interdenominational Ministers’ Alliance of Washington, D.C. in 1938.

In a booklet entitled Gold Everywhere that was published in 1945, Dr. Holloman, who in a life of service to his community and on a salary that never amounted to more than $6,000 per year, enunciated the philosophies that guided him from his life as an ex-sharecropper to the eminence he held at his death, A few of these quotations and statements are listed below:

“Again other people wherever you announce the doctrine of “Gold Everywhere,” almost invariably say: “Well, I want to get my share.” But “Gold Everywhere” is not a promise of a formula for easy money, but It Is a series of suggestions which we believe if adopted by an individual or group of Individuals will Invariably result in a great improvement to their Intelligence and to their standard of living, and consequently lead them on to extraordinary success in their chosen fields of endeavor. Let us scorn then the idea that there is an easy road to permanent and effective success. It is for us to subscribe again to the age-old doctrines “Without great labor, there is no excellence.”

“It would be a fortunate thing indeed if the citizens of the United States as they are now passing through the crises of World War II, would suddenly realize as never before that they are capable of becoming the very best hope of the whole world.”

“There can never be any substitute for hard work. No matter how clever or brilliant human beings may be, in the last analysis somebody must do the hard work.”

“It is possible for people to dwell too long on their disadvantages and handicaps and consider too seriously their frontiers and limitations, and forget entirely the dynamic circumstances which may lead to sovereign power. Take up no time with people who tell you how a thing cannot be done, or who tell you what you cannot dog but always be inclined to the man who has a formula of how it can be done and who has the genius for inspiring you to do what should be done.”

“It is necessary that men should always be in quest of knowledge, for there will always be so many things that we do not know. It is a most distressing fact to discover that a large section of the human family does not seek to extend its horizon at all. A man settles down to the humdrum of life, to do the same thing in the same way for forty or fifty years and then at the end has the nerve to call himself a success.”

“Probably there will always be In every society powerful organized groups that will be seeking to shut out and. put to disadvantage the unorganized minorities…. The American Negro should never forget however, that as long as it is possible for two men to stand together and plan together, to work together -his condition is not only not hopeless, but it is fraught with the greatest possibilities.”

“If I were a public educator assigned to the task of creating new school curricula, I should certainly emphasize the study of those extraordinary human beings who by dint of courage and Industry have projected themselves beyond the rank and file of their fellows and. have become the leaders of their day. For American Negro children I would want to make the examples of Frederick Douglass, Booker To Washington and a host of other black men who counted their lives not dear unto themselves that they might win some new heritage of freedom for themselves and for their people, as sources of eternal Inspiration.”

When one examines this extraordinary family, one frequently has to ask oneself: “Why has there been such a continuity of excellence? For all family members seemed determined to excel and to share their expertise. On the February 1975 cover of Black Enterprise, there is a picture of Rosa Holloman’s son, Dr. John L.S. Holloman, Jr., and a caption: “America’s Most Powerful Hospital Administrator.” He Is certainly that, for as president of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, he has under his wing 19 municipal hospitals with a capacity of just under 15,000 beds and a budget of nearly $1 billion a year. He is also New York City’s highest paid civil servant at $65,000 per year.

I can only suggest that the drive and energy that this family has exhibited in every generation may have something to do with the appearance in every generation of very strong men who were determined to resist the buffeting of racist winds. I know that this vague hypothesis is fodder for the Moynihans who see black family life as being in complete disarray and who blame feckless black men for their own victimization. Daniel P. Moynihan it must be remembered, as Assistant U.S. Secretary of Labor, asserted In 1965 in his Moynihan Report, that all vestiges by slavery. He went on to state that after blacks migrated to the cities from their agrarian base, high unemployment and lack of skills prevented the males from working and thus effectively destroyed their traditional husband/father roles. The sons, despairing of their father’s ineffectiveness, grew up like them, and were unable to take full advantage of the educational and occupational opportunities that were# however difficult to grab, still essentially attainable. The “heritage of slavery” became the catch-all phrase to explain away the despair and degradation of the ghettoes of this country. And It seemed for awhile, that Moynihant the descendent of Irish Immigrants would have black people behave as Irish peasantst faithful to the land and the Virgin Mary.

When one examines this extraordinary family, one frequently has to ask oneself: “Why has there been such a continuity of excellence? For all family members seemed determined to excel and to share their expertise. On the February 1975 cover of Black Enterprise, there is a picture of Rosa Holloman’s son, Dr. John L.S. Holloman, Jr., and a caption: “America’s Most Powerful Hospital Administrator.” He Is certainly that, for as president of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, he has under his wing 19 municipal hospitals with a capacity of just under 15,000 beds and a budget of nearly $1 billion a year. He is also New York City’s highest paid civil servant at $65,000 per year.

|  |

| Judge and Mrs. Barrington Parker at a reception in Washington, D.C. | Judge and Mrs. Barrington Parker at a reception in Washington, D.C. |

I can only suggest that the drive and energy that this family has exhibited in every generation may have something to do with the appearance in every generation of very strong men who were determined to resist the buffeting of racist winds. I know that this vague hypothesis is fodder for the Moynihans who see black family life as being in complete disarray and who blame feckless black men for their own victimization. Daniel P. Moynihan it must be remembered, as Assistant U.S. Secretary of Labor, asserted In 1965 in his Moynihan Report, that all vestiges by slavery. He went on to state that after blacks migrated to the cities from their agrarian base, high unemployment and lack of skills prevented the males from working and thus effectively destroyed their traditional husband/father roles. The sons, despairing of their father’s ineffectiveness, grew up like them, and were unable to take full advantage of the educational and occupational opportunities that were# however difficult to grab, still essentially attainable. The “heritage of slavery” became the catch-all phrase to explain away the despair and degradation of the ghettoes of this country. And It seemed for awhile, that Moynihant the descendent of Irish Immigrants would have black people behave as Irish peasantst faithful to the land and the Virgin Mary.

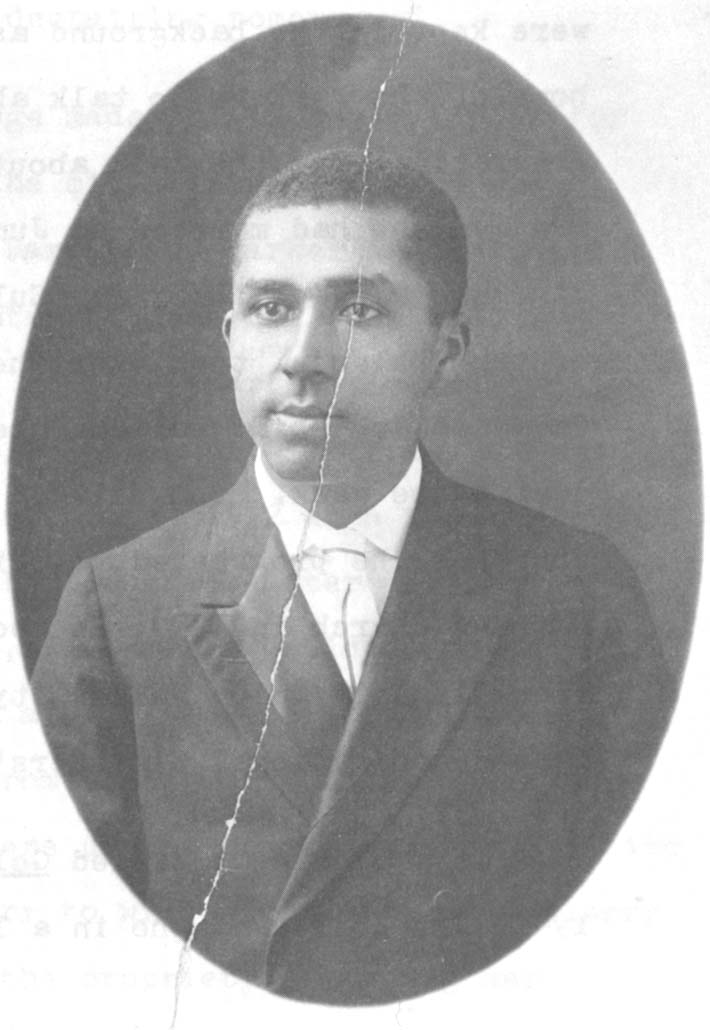

There is now a new “revisionist trend” In black family studies, and Dr. Richard A. English, a professor of social work and associate vice-president for academic affairs at the University of Michigan is part of that trend. He wants to examine the 75 percent of the black families that Include husbands and wives Instead of the 25 percent that do not. He says: “Unlike any other domain of American social life, the study of black families has been characterized by myths, stereotypes and unvalidated generalizations.” To expose theme myths, English and his colleagues are using federal census data. English notes that: “One study found that 77 to 90 percent of the black families in several northern and southern cities in the late 1800’s were two-parent households. The same was true for 76 percent of all black households In Philadelphia in 1880 and 1896, and for 82 percent of all black households in Boston in 1880.” What all this means, of course, is that more study is necessary before we can begin to authoritatively speak of the cohesion, success or failure of any black family. But Dr. Marjorie H. Parker, one of the winners (along with Senator Charles Mc. Mathias and Les Whitten) of the Henry W. Edgerton Award given yearly by the National Capital Area Chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union may have signaled to the assembled luminaries that the end to easy answers about black people was upon us, when at the Awards dinner held at the Sheraton Park hotel In Washington, D.C. last December, she called upon them to find cut about the character and brains of the people they would easily dismiss, and when she challenged them never to accept placidly any man’s degradation. Robert Shelton Jones must have smiled from his grave.

| The Parkers of Washington, D.C. In January 1970, at the swearing-in ceremony of Barrington D. Parker, Sr., as a U.S. District Court Judge. |

Received in New York on May 6, 1975.

©1975 Orde Coombs

Orde Coombs, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Coombs and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.