She sits in the morning room of her daughter’s house on Fessenden street in Northwest Washington, and as the memories come surging back, she struggles with her tears and says: “You must remember that I am 85 years old. I’m the only one left.” Her face is still smooth even though her hair is white, Her eyes are rheumy from the toll of years, but her voice is still strong and her hearing good. She is covered up this spring morning because she has not been feeling well lately, and. the stroke she had two years ago has diminished her strength, so that she now spends much of her waking hours In a wheel chair and Is constantly watched by a full-time nurse with a ferret face, fluttering hands, a gold dot pierced in the center of her forehead and whom everyone calls Frenchie.

The old woman is Rosa Jones Holloman, the daughter of a slave, born November 7, 1888 to Robert Shelton Jones and Carolyn Freeman Jones who were slaves In Albemarle County, Virginia, on the Dabney and Wingfield plantations. Of the seven children born to this couple, two died In infancy: The only son, who was named after his father, and the last child, called Carolyn after her mother who died giving birth to her. Of the five daughters: Minnie, Sarah, Louise, Rosa and Nellie who survived childhood, only Rosa lives. Last year Nellie died, and in telling this, the old lady says: “We were close, you know. We lived in Washington, we raised our children here, and we saw them become men and women we were proud of. I’ve been blessed, I know. Still its lonely being the last of your generation.”

But there is no reason to shed tears for the current loneliness of Rosa Jones Holloman. For her life is a thundering affirmation of the ability of the human spirit to prevail. And as she sits in this white and green brick house on a quiet street in Washington where houses sell for over $150,000; as all the symbols of solid American middle class status float around us, as her nurse and the housemaid patter around this elegantly furnished house, it is easy to forget the terrible days of 1888 when this gentle woman was born.

She tells the story calmly enough: “All of my father’s people worked for the Dabneys, and they had lived in Albemarle County for a long time. But in 1862 or 1863, the Dabneys sold my father and his younger brother to a plantation in Tallahassee, Florida. To this day I am not sure why they did it. Maybe they were short on money or something, and I seem to remember something about a gambling debt being mentioned, but I don’t know, and I only want to say what I know for sure, However, there was a lot of sadness because they had been sold, and he promised that he would come on back as soon as he could. Don’t ask me how he planned to do that. Well, as you know, there was a war going on, but that was way before my time. From what I can find out, though, there wasn’t too much disruption where my father’s family lived. At the end of the war, he made good his promise, and he came home one day in fine style. He had walked from Tallahassee to Charlottesville. It must have taken him months, but when he got near to Charlottesville, he jumped on a train, and came home as if he had traveled in luxury.”

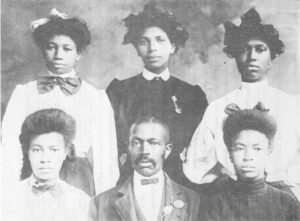

| The family of Robert Shelton Jones: Rose Jones Holloman is seated at the left. |

Robert Sheldon Jones set out to raise a family. He courted Carolyn Freeman Jones who had worked as a cook for the Wingfield family, and after a little while, he began to work for that family also. After a few years, he bought a piece of land from a man named Worthenbaker and after working for the Wingfields; he would then cultivate his own land. “He didn’t know the meaning of not working, ” says Rosa Jones Holloman. “He was a small man, and very disciplined and controlled. He felt that hard work had been his life when he was a slave, and that if he could work hard for someone else, he could work harder for himself.”

The children began to arrive. He had always wanted a son, and when his only boy died, he kept on hoping for one as he added to his family. With the death of his wife in childbirth, he became both father and mother to his daughters. Rosa remembers: “He would come home from the fields bone tired, and then he would begin to ask us how things went, if we had taken care of this, if we had learned that. Oh! he was a great one for discipline and education.”

It was his penchant for education that made him take advantage of what schooling could be found for blacks In Albemarle County, and made him send all of his children to the County school in Albemarle that had been erected after the slaves were freed. In l904, Rosa, now 16 went away to Hampton College. She had been an alert and diligent student in high school, and her father was readily persuaded that she should leave home to try to get an education. She stayed five years at Hampton# because she had to pay her way by working in the laundry, and so she could not complete the course of study in four years. When she is asked if she has fond memories of Hampton in those days, she smiles and mutters to herself. And then says, loudly, “The arrival of those colleges in the South saved us. We knew that people cared and we knew that no matter how bad it could get – and remember around the turn of the century it was very bad – we would do better every year.”

In 1909, Rose Jones left Virginia for North Carolina. She had been offered a position at Waters Training Institute In Winton, N.C., and although she had given some thought to going on with her studies, she felt that she could not turn down this job, since her younger sister, Nellie, was going to enter Hampton in the fall and money would be needed to pay tuition fees and for her upkeep in the college. Waters Training Institute was entirely supported by missionaries from the North, and the twenty-year-old Rosa Jones found it exalting and rewarding, “We would got a lot of students, from the country who were eager to learn but had not been properly prepared. And we would look at the faces of the parents who brought them. They seemed to think that we could do wonders for their children, that we would teach them noble things and that they would find their way in the world and that God would always be with them. It always seemed to me to be such a big responsibility but I knew that if I did my best, I would find a way to help those who needed help.”

She not only found her way but also a husband. John Lawrence Sullivan Holloman was a teacher of Mathematics and Latin at Waters Training Institute. He was born on April 24, 1885 in rural Bertie County, North Carolina, and when his father died, young John, at 16, the oldest of 10 children, took over as the head of the family. He had been educated at Waters, and had developed such a gift for speaking in rural churches, that he was channeled into the ministry and educated at Virginia Union University, a Baptist school in Richmond, Virginia.

On June 12, 1912, Rosa Jones and John Lawrence Sullivan Holloman were married on Robert Jones’ farm in Albemarle County, Virginia. From this union there were five children: Carolyn, Jessie, Marjorie, Lawrence and Grace. And when John Holloman died on May 6, 1970, he had spent 53 years as pastor of the Second Baptist Church in Washington.

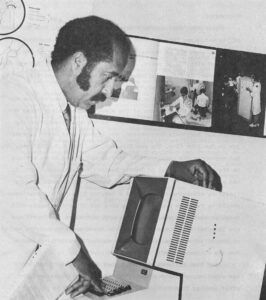

| photograph: Dr. J.L.S. Holloman, Jr., the new Director of the Health and Hospitals Corporation, New York City. |

Asked what she remembers most about her husband, Rosa Holloman smiles and says: “His devotion to us, to God, to the goodness in Man.” And when she is pressed for a sharper definition of the man she lived with for 58 years, she says: “An achiever. My husband was an achiever. He didn’t believe that anything was impossible, and he gave all of us that belief.”

She must be right, for on April 3, 1974, the son of Rosa and John Holloman, the grandson of the slave Robert Shelton Jones was sworn In by Mayor Beame of New York as the new Director of the Health and Hospitals Corporation, the highest paid civil service job in New York City. The new Director, Dr. John L.S. Holloman, Jr., had announced his commitment to service and change in an article in the American Journal of Public Health in September 1970. He had stated that: “A national health program which would address itself to achieving and securing a healthy life for all Americans should be designed now. It can be done now if professionals will remember that they are part of society, not above it. Physicians are licensed by and are privileged to serve society, and the health of the nation must be accepted as a nonprofit national endeavor for the ultimate benefit of mankind.”

When Rosa Holloman was asked what she thought of her son’s new position, she said simply: “He cares and he works hard for other people. That is always a good combination.”

Received in New York May 17, 1974

©1974 Orde Coombs

Orde Coombs, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Coombs and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.