Manuel Aceves is so hip that a leading Mexico City newspaper has suggested that the death penalty should be invoked in his case despite the fact that Aceves has committed no crime.

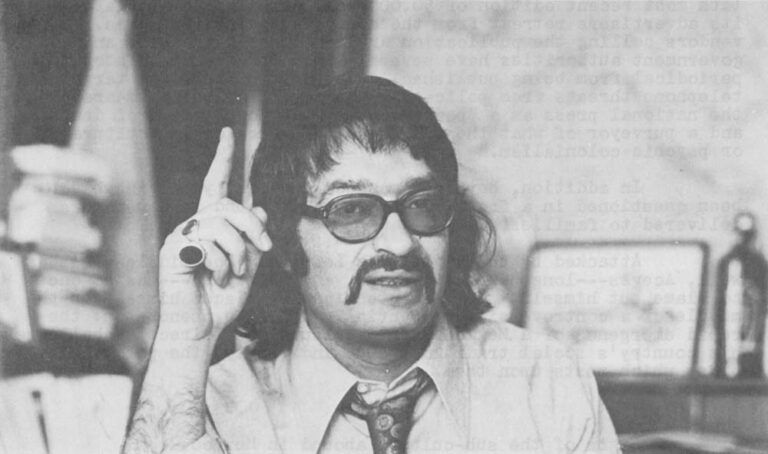

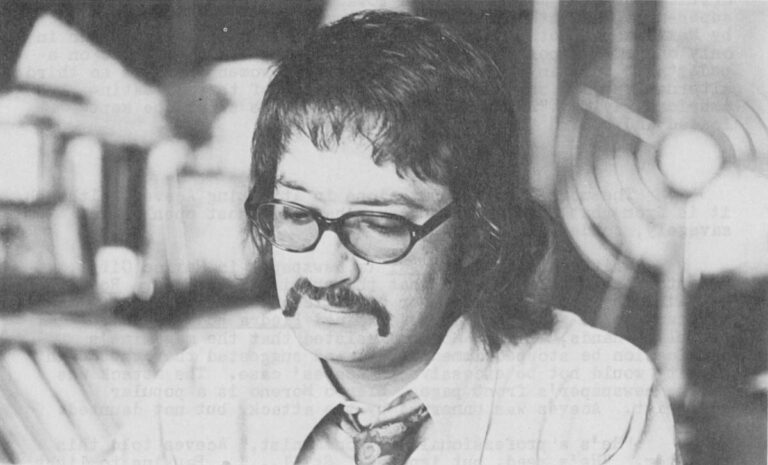

Aceves is the publisher and editor of Piedra Rodante, a semi-slick bi-monthly magazine that champions Mexico’s budding youth-culture.

While the circulation of his magazine climbs dramatically (its most recent edition of 50,000 sold out almost immediately), its advertisers retreat from the controversy it stimulates. Street vendors selling the publication are sometimes harrassed, and government authorities have several times threatened to stop the periodical from being published. Aceves is himself the target of telephone threats from policemen, and he is variously smeared in the national press as a “pornographer,” a “popularizer of drugs,” and a purveyor of what the political Left here calls “cultural or psychic colonialism.”

In addition, both his manhood and family origins have been questioned in a frank way not usually found in newspapers delivered to families.

Attacked by the Right, the Left, and the middle-class as well Aceves — long-haired, affable, and thirtyish — has no one to blame but himself. He has intentionally placed himself in the middle of a controversial, potentially volatile phenomenon: the rapid emergence of a Mexican youth-culture that directly challenges his country’s social traditions and, indirectly, the political order which rests upon them.

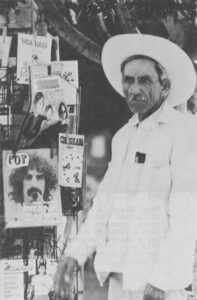

Signs of the sub-culture abound in Mexico.

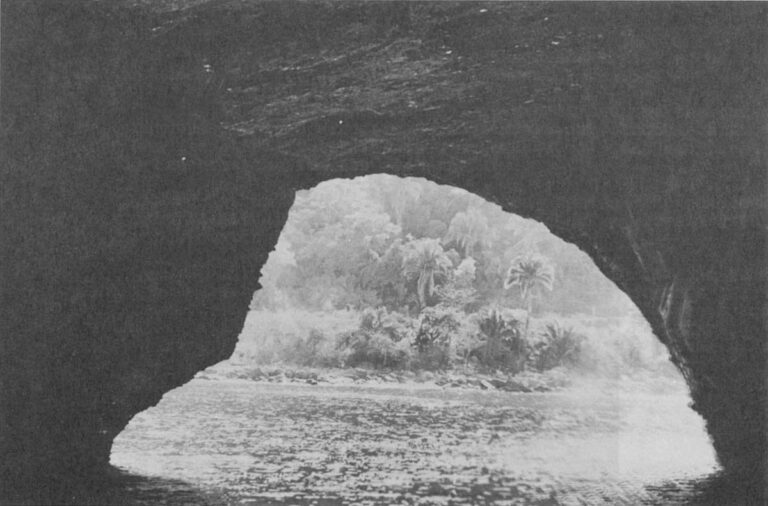

Long-hair, bell-bottoms, mini-skirts, and peace symbols are firmly entrenched in the fashions of the urban young, while local rock bands spring up in villages that have yet to encounter the telephone. Transistorized radios deliver the Rolling Stones’ latest hits to Indian enclaves deep in the mountains of Jalisco and Oaxaca, while youths in Guadalajara take advantage of rock “fiestas” in crumbling warehouses or in the city’s parks. While an increasing number of teens leaves the small towns for the excitement of the big cities, rural communes begin to emerge in the somnolent, dirt-cheap fishing villages on Mexico’s south-west coast. And everywhere that the young gather the saccharine smell of marijuana mixes with hard-rock music to produce a blend recognizable to the young of any country.

The editorial offices of Piedra Rodante are five floors above the Pasaje Londres, or “London Passage,” in Mexico City’s very plush “Pink Zone.”

Aceves’ own office is modest and comfortable, lined with books and dominated by a large wooden desk whose surface is covered with manuscripts, pencils, art-work, love mail, hate mail, and the material for the next edition.

Until recently, those editions were characterized by a wealth of material from the Rolling Stone, a popular American magazine devoted to music and counter-culture. Indeed, Piedra Rodante is itself named after that publication. But today the Mexican magazine is independent of its namesake, using little of the other’s material and emphasizing local subjects instead.

Aceves declines to elaborate upon his magazine’s split with Rolling Stone other than to say that “They treated us like muchachos, like little boys.”

So long as the Mexican magazine was dominated by American themes there had been relatively few problems. It was not until Aceves began to dwell on local issues that he found himself viciously smeared, his advertisers harrassed, his vendors threatened, and his right to publish questioned by government authorities.

There are more than enough local subjects and issues to treat. They range from women’s liberation to riots to drugs to rock-festivals to communes, and Piedra Rodante can usually be relied upon for objectivity, thoroughness, and restraint. That review cannot be applied indiscriminately in Mexico and, in fact, it may be said that Aceves’ difficulties arise more from his magazine’s merits than from any faults it may have.

Charges that Aceves is “a popularizer of drugs” stem from his publication’s sophisticated perspective on that subject, and its editor’s insistence on discrimination. Marijuana, for instance, is the recipient of a generally benevolent glance, while the so-called “magic mushrooms” are exhaustively discussed in an entire issue devoted to that subject. Glue-sniffing, which Aceves says is epidemic among young Mexicans, is exposed as a menace, as is heroin.

Further, each issue of the magazine contains a column, written by a physician, whose subject is dope, its availability, characteristics, price, and effects. Moreover, the magazine accepts advertisements for paraphernalia associated with smoking pot — the kind of thing one finds in any American magazine oriented toward youth. All this while the Mexican and American governments conduct a vigorous campaign to suppress drugs of any kind — a campaign which, in Mexico, is characterized more by a will to persuade than to inform.

“All drugs lead to jail, suicide, or murder.”

“Magic mushrooms are promoters of crime.”

“A drug-abuser is a living dead-man — dangerous.”

“Denounce all drug-traffickers to the police.”

The quotations are from the magazine Auxilio! — SOS, a conservative publication characterized by a Victorian moral pose. The same issue which featured the above aphorisms on the bottom of each page was devoted to two stories about youth-culture which were certain to boost circulation. One, purporting to be a report on a Mexican rock-festival (called Avandaro) held in the Valle de Bravo, was headlined: “Avandaro: Waterloo of the Old Morality: 150,000 youths in an orgy of sex and drugs.” The second report was entitled “SATAN MANSON: and his Band of Beautiful But Bloody Hippies.” (Their caps.)

Another publication, the photo-magazine Casos de Alarma, described the same festival as “a vicious and degenerate Inferno” of “drugs and sexual perversion.” Such festivals, and the hippismo which makes them possible, editorialized that magazine, “threaten to destroy our youth.” Appealing to the nationalism of its readers, Casos de Alarma wrote that “The worst of it is that it’s all by imitation (of American hippies).” Moreover, the editors concluded piously, “When one lives in family harmony, the hair does not grow so long….”

Auxilio! — SOS, not to be outdone, added that Avandaro “would have been the envy of a Nero or a Caligula.” The message was clear.

And yet it must have surprised the authorities because the official judgement, which Aceves shared, was that the festival presented few police problems other than those of traffic jams and littering. Certainly Nero and Caligula would not have been shocked, and the only evidence of “sexual perversion” was a photo of a girl dancing while nude to the waist.

It is partly Aceves unwillingness to echo the carefully-rehearsed shock of the popular press confronting youth-culture that has caused him to be branded a pornographer. Certainly his friendly interview with “The Naked Lady of Avandaro” (who partially disrobed at the rock-festival) did not endear him to Mexican parents. Nor have un-biased stories about run-aways and “groupies” helped Piedra Rodante’s image any more than have wry articles about America’s Plaster-Casters (a women’s group devoted to making plaster casts of rock idols’ penises).

To call Aceves a pornographer, however, is to stretch the Victorian moral perspective to its breaking point. Nevertheless, the charge is made, although it is directed not so much at any particular article or photograph, but at the magazine’s insistent challenge to traditional Mexican (and Catholic) attitudes about women’s roles, birth control, and sex in general.

Advocating the liberation of Mexican women from the rigid roles in which they are today confined, the magazine is sharply critical of many male attitudes toward women, the macho ethic of the super-male, and other traditional views which, however cherished by Mexicans of both sexes, conspire to place the Mexican woman in only one of two possible positions: supine in bed, or erect on a pedestal. For many, perhaps most, Mexican women there is no third alternative, and she must live the reality of the old Latin-American saying: “A woman is like a gun — she should be kept loaded and behind the door.”

The moralists are not alone in attacking Aceves, although it is from that quarter that Aceves has been most openly, and savagely, condemned.

Writing in El Universal (a newspaper in Mexico City), Roberto Blanco Moreno urged that the publisher of Piedra Rodante, be jailed by the government for his “vicious corruption” of Mexican youth. Saying that he examined Piedra Rodante “with trembling hands,” Blanco Moreno insisted that the magazine’s publication be stopped immediately and suggested that the death penalty would not be excessive in Aceves’ case. The attack was on the newspaper’s front page. Blanco Moreno is a popular columnist. Aceves was unnerved by the attack, but not daunted.

“He’s a professional anti-communist,” Aceves told this reporter. “He’s read, but ignored. Still….” Pausing to light a cigarette, he responds to a question with a shrug. “Yes, I could sue for damages. He’s called me a pornographer, a bastard, a popularizer of drugs, and he says I’m not a man. But this is Mexico: it wouldn’t get me anywhere. The courts are completely corrupt.”

By themselves, the attacks from Mexico’s “moral middle” would be difficult enough for Aceves. Coupled with the spectre of Right-wing extremism and vigilante activity, sharp criticism of youth-culture from the Left, and a combination of intimidated advertisers and a shrinking publication budget, Aceves is in considerable difficulty.

“We can’t survive on circulation alone,” he says. “We must have the advertising. But,” he adds with a forlorn smile, “we can only afford one ad-man. That is because he works for nothing.”

In the United States, the alliance between what has come to be called “youth-culture” and the political Left is largely taken for granted.

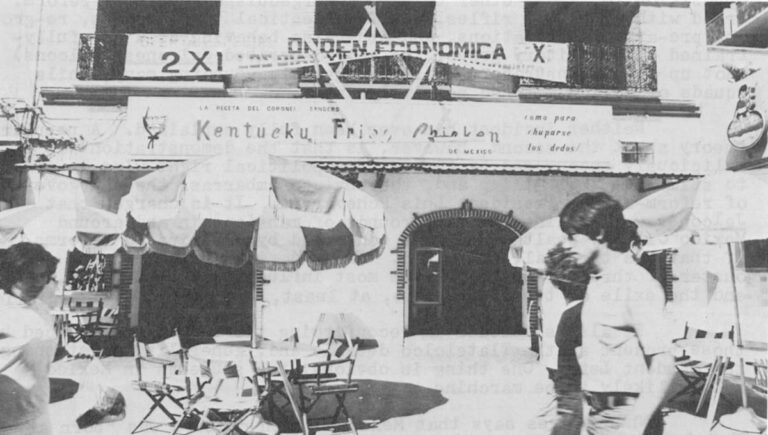

Not so in Mexico where the Left tends to view youth-culture as a C.I.A. plot to “Americanize” a country already questioning its dependence on the American economy. The phrase that is used is “cultural or psychic colonialism” and it is directed as much at long-hair and rock-and-roll as it is at the mushrooming number of Burger Boys and Kentucky Fried Chicken stands.

That theme is perhaps most wittily articulated in Los Agachados, a monthly comic-book written and drawn by the Marxist satirist “Rius.” The cartoonist takes frequent jabs at long-hairs, finding little difference between visiting hippies and businessmen, television and rock-music.

All, in so far as Los Agachados and many Mexican leftists are concerned, are devised to subvert Mexican traditions in order to render the people more amenable to “Yankee imperialist exploitation.” In the same way, drugs are viewed by the Left as an homogenous tool designed to divert the young from what they believe to be an on-going “class struggle.”

Aceves, who’s avowed aim is to divert Mexico from what he says is its “pre-fascist” course, rebuts the Left’s rhetoric with a combination of humor and reason. He points to the fact that his magazine is striving to alter social conditions by challenging traditions and roles that are inherently reactionary. He celebrates Indian culture, fights repression where he finds it, advocates women’s freedom from constrictive sex roles and strongly supports the most progressive elements in the society. Moreover, he has not forgotten, as the Mexican Left apparently has, that youth-culture has its origins in political dissidence: that it bodes more, not less, agitation (directly or indirectly) for meaningful reform.

“Mexican youth-culture,” Aceves says, “was born at Tlatelolco. Everyone dropped-out.”

“Tlatelolco” is the name given to a 1968 demonstration in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco Square.

At that demonstration hundreds of Mexican youths, according to witnesses, were slaughtered by converging Army troops. Until the shooting — which began during speeches at the Square — the demonstration was, by all reliable reports, peaceful.

The event is still much discussed by both the old and the young. Usually reliable witnesses, including professors, an attorney, and several reporters, insist that the bodies of the young were confiscated from the streets and driven to Army encampments to be cremated: a particularly heinous act in Catholic countries. The victims did not, as a result, show up in any official body counts; many were simply reported as “missing persons.”

That massacre (no other word is apt) was followed in June, 1971 by another of smaller proportions, also in Mexico City. The second saw hundreds of youths, mostly long-haired and wearing bell-bottoms, converge in municipal vehicles upon a student march in opposition to, among other things, “bourgeouis educational reform.” Armed with clubs and rifles, wearing identical tennis shoes, re-grouping pre-arranged locations, and otherwise behaving as a carefully-trained para-military group, the self-described Jalcones (Falcons) shot up the demonstrators, killing several, wounding many, while squads of police watched passively on.

Neither incident has ever been fully explained. A popular theory about the second, however, is that the demonstration was maliciously encouraged by the extreme political right-wing in order to stimulate the killing andl thereby, to embarrass the new government of reform-minded President Luis Echevarria. It is charged that Jalcones were trained on the grounds of mansions in and around Mexico City by wealthy Mexicans concerned by anticipated reforms. If that was the goal, it failed. Instead it resulted in the ouster of three of Mexico City’s most influential politicians, and the exile of two of them: so, at least, goes informed speculation.

It also succeeded in reconfirming the terror experienced by those present at the Tlatelolco debacle and, generally, in stunning the student Left. One thing is obvious: the students in Mexico aren’t likely to be marching anymore.

When Aceves says that Mexican youth-culture was “born at Tlatelolco,” he hints at the dissident roots of youth-culture as it is found beneath the border of the Rio Grande.

Perhaps he does so somewhat defensively. Because the one charge which the Left, the Right, and the “moral middle” are able to agree upon is that the Mexican variety of youth-culture is “imitative” and nothing else.

As evidence of that charge, all three groups point to the fact that nearly all Mexican rock-groups sing in English although the language is not commonly understood. They note that the Jalcones, responsible for the deaths of so many students and the harrassment of so many others, wore bell-bottoms and long-hair. And they add that so many slogans seemingly espoused by Mexican kids have no real content for them, having lost their meaning in the transition across borders.

In this regard, one notes that the “peace symbol” is little more than a commercial decoration in Mexico; it signifies youth, if anything, and has little or no political connotation. In the same way, the “Weatherman handshake” popular among radicals in the United States has no political significance among Mexicans, though many use it. Moreover, it is not unusual to find an automobile decorated with both STP and swastika decals with its driver roaring through town flashing the V-sign and crying “Piz ‘n Lof” to every American in sight.

Aceves acknowledges the “imitative” aspect of youth-culture in Mexico, but sees it as an aberration that will be overcome as the sub-culture matures. “We know,” he says “that the Jalcones wore bell-bottoms, that they had long hair. We have photos of them. We even know they smoke pot.” Do they then also read Piedra Rodante? “No,” he says with an angry look, dismissing the question. “They read Casos de Alarma.”

Aceves has intentionally de-Americanized his magazine, retaining only those aspects of international youth-culture that are relevant to Mexico (he has, for instance, attempted to make “Peace and Love” more than a slogan to his readers).

Moreover, the casual Spanish student may have a difficult time reading Piedra Rodante because of its editor’s encouragement of the slang peculiar to Mexican youth culture. That slang (in which “yes” is Simon, “no” is Nel, and the “scene” is, cryptically, called “the roller-skate,” or El Patin) is an idiomatic way of closing the scene to outsiders, making it more Mexican, and bending the tradition-steeped Spanish language to make it more amenable to El Rock.

As it is now, lyricists writing in Spanish are in a position such that certain ways of relating to others are excluded from their songs by the language itself. It is as if the Beatles had been compelled by English to write “I Want to Hold Thy Hand” instead of the song they did, in fact, compose.

Aceves’ emphasis on slang is part of an ambitious design which includes encouraging Mexican rock-groups to compose their songs in Spanish.

That effort has already shown some fruits. Earlier this year, the first all-Spanish rock-album was produced in Mexico City by the Polydor firm. The album, performed by La Revolucion de Emiliano Zapata, a very popular Mexican group, was thick with slang. It was quickly withdrawn from circulation, however, when it was banned from radio-play due to its “controversial” lyrics.

In fact, the lyrics which caused it to be banned were no more “controversial” than others that are typically heard on Mexican radio. But what may be ruled innocuous in English is not necessarily so in Spanish, as “La Revolucion” quickly learned. Nevertheless, despite the banning, other groups are planning to produce albums in Spanish and it may be expected that English will, in a few years, fade from use as a code among the young.

If that should occur, and Spanish proves malleable to slang and Rock, then it may be expected that Mexican rock-groups will fulfill a function for Mexicans similar to that fulfilled by English groups for Britons and Americans.

That is, such groups would come to serve as the political and moral consciences of the Mexican young.

In other words, Mexico may expect, if the current trend continues, to produce a native Bob Dylan or John Lennon. Only then can El Patin (it is also called La Onda, or “the wave”) be expected to take its own form.

It is for this reason that Aceves can deny the reality of what is called “Chicano Rock,” which he apparently views as about as Mexican as the igloo.

Chicanos, or Mexican-Americans, singing in English about experiences largely shared north of the border are Mexican only by descent. Their experience, however valid, is unique and not necessarily one which most young Mexicans can fully share. “There isn’t really any such thing as Chicano Rock,” Aceves comments.

The implications of an emerging maturity in Mexican youth-culture are potentially far-reaching.

If Mexican-rock follows the pattern of other varieties (and there are definite signs that it is), it may be expected to challenge a broad spectrum of Mexican tradition.

Already La Revolucion de Emiliano Zapata (whose “Nasty Sex” and “Lost City” sold more than 500,000 copies in Mexico) has assaulted restrictive sexual attitudes toward women and, more recently, emphasized their anti-establishment stance in a song called “I’m a Revolutionary.”

Other groups may soon be expected to follow and, given the ubiquity of the radio, one may anticipate an increasing politicization of the Mexican young.

Indications of that politicization may already be found on walls around Guadalajara and Mexico City where graffiti artists have (apparently intentionally) confused Lenin and Lennon.

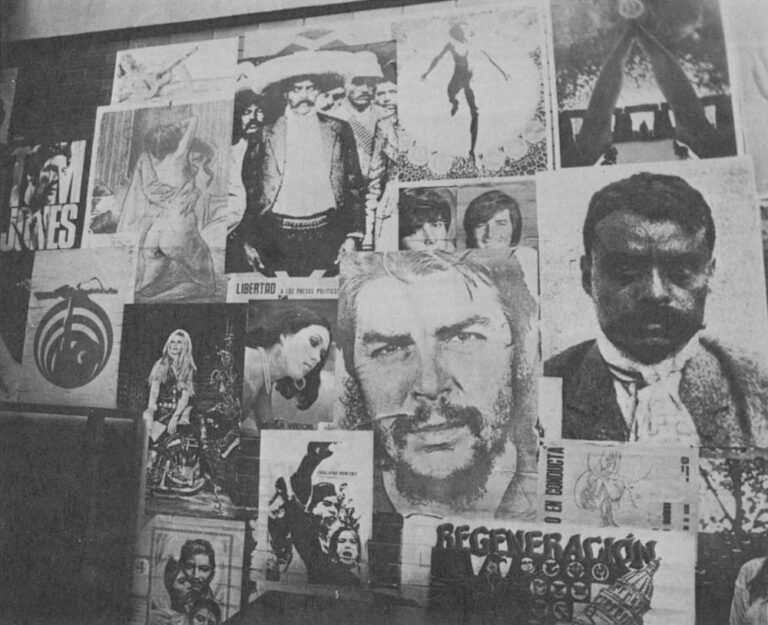

Indeed, at the Autonomous National University of Mexico, (UNAM) in Mexico City, the student cafeteria is papered with a sprawling poster-collage which mixes sex, transcendentalism, and revolution in one heady brew.

The collage, which covers an entire wall, juxtaposes Pancho Villa, Tom Jones, Emiliano Zapata, Brigit Bardot, The Rolling Stones, Meher Baba, and Goya nudes beside numerous images of “Che.”

Whether this is a sign of enlightenment or confusion may be subject to debate, but the students at UNAM are obviously comfortable with the somewhat kaleidoscopic relationship. Indeed, in the land of the charro (a romantic cowboy figure), it may well be that Mick Jagger is as potent an instrument for change as Pancho Villa was.

In any case, that’s what Aceves is betting upon. As he puts it, “The conventional Left is in a state of confusion here. They do not understand the implications of youth-culture.”

And, if opposition from the Establishment (Left, Right, and Middle) is any index to a phenomenon’s capacity to invoke change, then youth-culture should prove to be a potent catalyst. If it does, Aceves will have been at the center of its beginning.

Received in New York on March 6, 1972.

©1972 Jim Hougan

Jim Hougan is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Hougan, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.