July 21, 1972 Magic Center Western Asphalt Jungle (Amsterdam)

At 41, Kees Hoekert claims to be the greatest and most skillful dealer of marijuana in the Western Hemisphere.

He may be right. As head of the Lowland Weed Company, this intense, affable Dutchman is charged with the loving care, maintenance, and distribution of enough marijuana to keep the counter-culture high for as long as they can handle it.

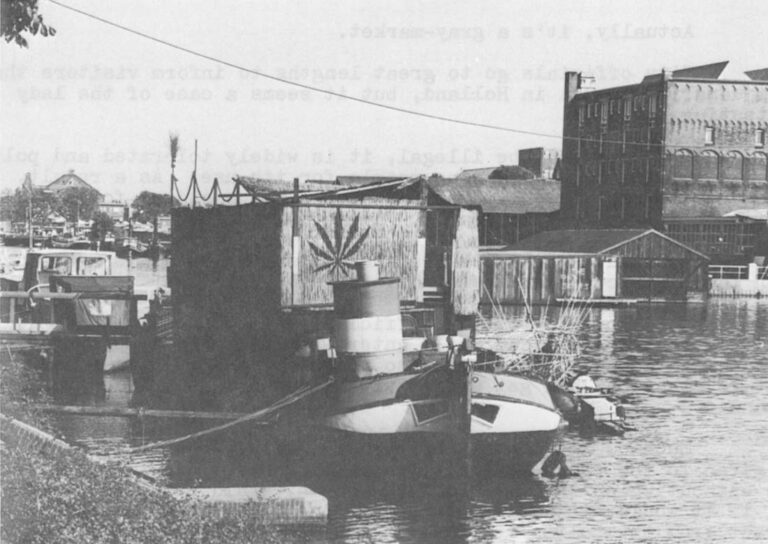

The company offices are aboard a comfortably dilapidated barge moored in Amsterdam’s Kattenburg Canal directly across from the local police station. The site is somewhat historic since it fronts upon the former location of the Dutch East India Company.

Moreover, it’s not difficult to find (and Kees likes visitors) because the company boat is emblazoned with a 5-foot high painting of a marijuana leaf. Fore and aft, to starboard and port, topside and inside, a few thousand marijuana plants grow to maturity in weather that made the tulip famous.

The story of the Lowland Weed Company is a rags-to-riches saga that began when Hoekert discovered, in 1963, that marijuana “of a fine quality” could be grown in Holland.

“Can you imagine,” Hoekert asks, “what it meant to me? An ordinary Dutch burgher dreaming of Walter Mitty? It was like discovering gold mines on your property! The first reaction I had was to hide it from my neighbors and get rich.”

But he didn’t hide it.

Instead, the budding and resourceful entrepreneur journeyed to one of Holland’s strangest and most provincial cities, Staphorst, a small community of rigid Calvinists. So culturally isolated is Staphorst, and so orthodox is its Calvinism, that art critic Sacheverell Sitwell once described it as “one of the seven wonders of the world.” Even the Nazis, it is pointed out, left Staphorst alone during their World War II Occupation of the Netherlands.

In Staphorst, Hoekert finagled the use of 4 acres on an experimental farm that was run under (apparently removed) government auspices.

“We were planting pot with a tractor. The farmers did it for me. They were working for the state and harvesting the marijuana without ever knowing what it was. Before long, I was dealing tons of the stuff that I’d stored in a hayloft to dry.”

Selling primarily in Amsterdam, Hoekert quickly flooded the market with his product, lowering the illicit retail price from $300 per pound to about half that amount. “I was making a million,” he explains, “I was becoming a capitalist.”

“But capitalism,” Hoekert notes, “is the only disease you can get rid of in one day. You just invite your friends to your house, and give everything away. You’ll find that friends are always ready to help in this way.”

Is that what he did?

“Of course not,” Hoekert says. “I put all the money in a Swiss bank. That way it is not taken by taxes. Today, I am a millionaire, but I don’t know what to do with the money. So, I sit here and await suggestions. Perhaps one day a good suggestion will arrive and we can make use of my fortune.”

City officials go to great lengths to inform visitors that marijuana is illegal in Holland, but it seems a case of the lady protesting too much.

While pot may be illegal, it is widely tolerated and police are discouraged from arresting people for its use. As a result, young people smoke openly, passing hash-pipes back and forth while policemen direct traffic nearby. In movie theaters and at dances the sweet smell of cannibis wafts amid the crowd without controversy becoming aroused. Only dealers and users of hard drugs are sought with the vigor customarily found in other countries.

It is because of this officially-established laissez-faire attitude that Hoekert can daily entertain literally dozens of friends and acquaintances in the manner to which he, and they, are accustomed. That is, they can all get stoned without simultaneously getting paranoid.

Much of the credit for the permissive freedom of Amsterdam is given to the Provo movement, in which Hoekert figured prominently, and without which the Lowland Weed Company would not exist today. Or, if it would, it would not be floating less than 50 feet across the street from the police station; it would be underground.

“UNDERGROUND!,” explodes proto-Provo Jasper Grootveld. “WHAT IS UNDERGROUND? We do not believe in underground. We cannot afford an underground in Holland. Already we are beneath sea level! Underground is water and we drown.”

Grootveld, Hoekert’s best friend and generally acknowledged as the founder of the Provo movement, punctuates his always metaphorical speech with painful finger jabs at the chest of whomever is listening. “We open up the underground,” he says, jabbing vigorously. “We communicate through mis-understanding! We are fools! Village idiots! Very important to the community. Everybody likes the village idiot!”

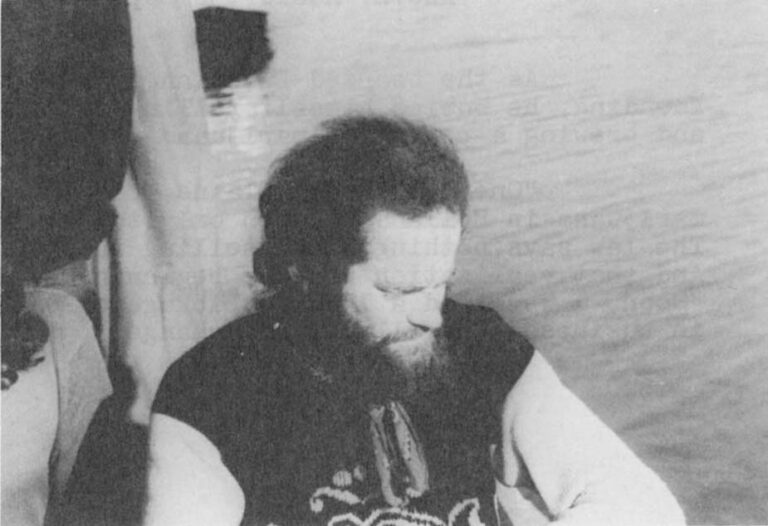

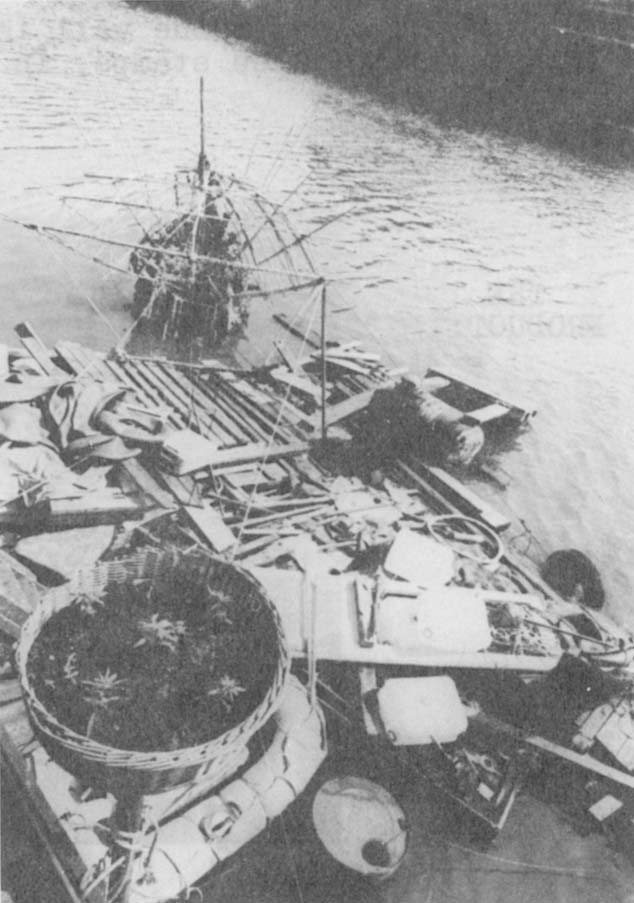

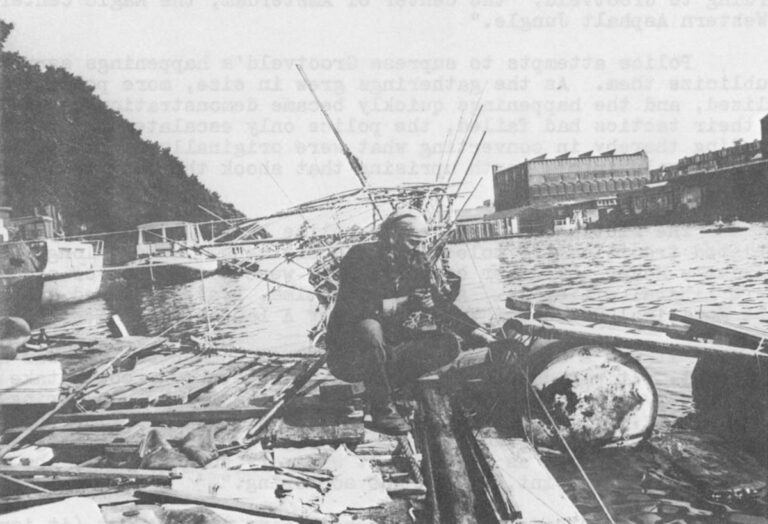

Grootveld preparing his craft for the odyssey to Sweden later this Summer. “First,” he prudently noted, “I must learn to sail.” In the foreground is the crow’s-nest, budding with young marijuana plants.

A loosely-knit group of anarchists, Provo emerged during the mid-1960s when restless Amsterdam youths gathered at the fantastic “happenings” organized by Grootveld. Each Saturday night, the powerfully-built, working-class provocateur would arrive at the statue of the Lieverdje. Donated to the city by a cigarette manufacturer, the statue of a little boy came to symbolize for the Provos “the addicted consumer of tomorrow.” And the site on which it stood became, according to Grootveld, “the center of Amsterdam, the Magic Center of the Western Asphalt Jungle.”

Police attempts to supress Grootveld’s happenings served only to publicize them. As the gatherings grew in size, more police were mobilized, and the happenings quickly became demonstrations. Seeing that their tactics had failed, the police only escalated their efforts, succeeding thereby in converting what were originally small Saturday-night festivals into a youth uprising that shook the city with devastating riots.

The rioting, and images of police beating young people, infuriated traditionally tolerant Dutch citizens. Before long, Amsterdam’s Mayor and other conservatives were forced out of office by more liberal officials. At the same time, Provo captured a seat on the Municipal Council (“Vote Provo For A Laugh”).

“It was a nice revolution,” Hoekert comments. “It was not a coup d’etat. It was an open revolution which everyone could take part in. I am very satisfied now. Before Provo, Amsterdam was boring, boring, boring, boring, boring, boring. It was as boring as Copenhagen, as boring as Stockholm, as boring as Brussels, as boring as East Berlin, as boring as Moscow. It was very boring. Now,” he says, pausing to light a joint, “it is not so boring.”

While Amsterdam may have been boring in the past (it isn’t today), Provo never was. Its tactics of ridicule and provocation (which inspired America’s Yippies) galvanized the city’s youth into a maelstrom of political activity. An estimated 1500 “Provo-cations” took place in the movement’s three-year life-span.

But Provo success was fatal to it. As one disillusioned Provo remarked after the group’s electoral success, “No matter who you vote for, the government always gets in.”

A Provo Liquidation Committee was soon organized by the Provos themselves, and a funeral was held for the group.

Today, the Kabouters (elves, or dwarves) have succeeded Provo, using essentially the same tactics and many of the same people, but avoiding violent confrontations. They now hold five seats on Amsterdam’s Municipal Council, having picked up more than 37,000 votes in the last city election.

“But now,” says Jasper Grootveld, “the Work is different. The Work is the Lowlands Weed Company. We think what is needed is marijuana for all. If everyone would smoke, it would bring them to themselves.”

The “Work” at the Lowland Weed Company takes place in what psychologists like to call “a supportive environment.”

Bobbing gently on a wide, quiet canal, the barge is a popular rendezvous for hip vagabonds, Kabouter aldermen, poets, surrealists, pot-heads, freaky professionals, and Consciousness-III victims of every nationality. The conversation begins late in the morning and, sustained by Hoekert and Grootveld’s anecdotal wit and potent dope, continues throughout much of the night. In one six-hour period recently, more than 30 people dropped in to turn on, buy some plants, or just to reminisce about the good old days of the Provo phenomenon. More than anything else, life on the barge resembles a round-the-clock television talk show held in a floating, alternative nursery.

Indeed, in an age when visions are at a premium, it may be said that the Lowland Weed Company’s cup runneth over.

According to Hoekert, the dope-boat is organizational headquarters of a European reforestation project that uses the tactics of Johnny Appleseed to sow Nepalese cannabis wherever the counter-culture travels.

“To date,” Hoekert says, “about 60,000 of our seeds have been sown in France, Spain, Italy, and Germany.” So far there have been no reports on the program’s success, but Hoekert is confident. “Marijuana,” he says, “what is it? A weed. There is nothing that is easier to grow than a weed. It grows anywhere. And our’s? Well,” Hoekert says, gesturing at the wall, “ours is the best.”

Tacked to the wall is the original burlap package, replete with faded Nepalese stamps, in which the first 15 kilos of seeds arrived.

But it isn’t all conversation and hyper-ventilation on the barge. There is also work to be done on an ongoing project that threatens to reach fruition late this Summer. That project is the construction of a 30-foot sailboat which will carry Grootveld, Hoekert, and as much marijuana as can be fitted aboard to Sweden.

The sailboat (under construction next to the barge) resembles a bombed-out version of the Kon-Tiki. It is being built entirely from pollution — whatever flotsam comes down the canal. Driftwood, battered oil drums, split planks, blown tires, wrecked lawn chairs, tin cans, and industrial detritus are lashed together with odd pieces of rope and string. The sails, according to free-lance naval architect Grootveld, will be woven of hemp — presumably so they can be smoked in a calm. Quite literally, the sailboat will be a Dutch junk.

Why Sweden?

“We want to help the Swedes realize that Holland has the best drug laws in the world,” Grootveld explains. The reason for that mission is that an epidemic of amphetamine abuse among young Swedes was recently blamed on four Dutch nationals who were caught delivering large amounts of “speed” by small-engine plane to rural airports in Sweden. Many Swedes reacted by calling upon Holland to stiffen their progressive drug laws.

Grootveld’s alternative is to wean the Swedes from the use of hard drugs by substituting marijuana in their stead. “Rather than coming at night by airplane with a cargo of speed to sell,” he explains, “we will arrive slowly, by boat, with grass to give away. This is in the great tradition of Dutch naval history, you realize.”

Received in New York on July 28, 1972.

©1972 Jim Hougan

Jim Hougan is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Hougan, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.