September 28, 1972 Ibiza, Spain

The big blue van, a smear of dust and dents and rust, jerked into the central square of Santa Eulalia, back-fired and clattered to a stop.

Slowly, its back-doors opened, groaning on ancient hinges. And then, tentatively, putting one foot in front of another and finally sliding onto the pavement, out stepped —

Right. A wrinkled green giant with red horns and temple bells.

Right. A wrinkled green giant with red horns and temple bells.

George, an expatriate bartender who left New York for Ibiza’s solitude, who wanted to write the Great American Novel or, failing that, a very dirty one, swore to himself, grabbed his groceries, and left: the last time something like this happened the police took to beating anyone who wasn’t wearing a crew-cut or carrying a cane.

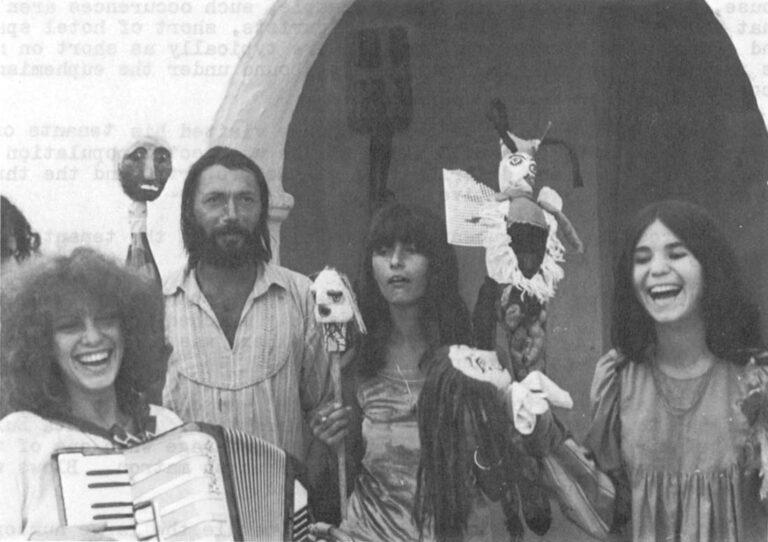

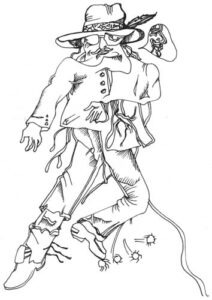

Meanwhile, the van was disgorging a painted cargo of wizards and elves, clowns and puppets, a French accordionist and a barking Dalmatian in period costume.

Somehow (people will watch anything) a crowd gathered. Spanish fishermen, farmers, German tourists, hippies and bell-boys gravitated toward the Square where the happening unfolded in three languages.

A lovely young girl with brown eyes the shape and color of almonds was walking on her hands. The accordionist, a towering, pencil-thin figure with an aquiline nose and a sorrowing expression, wrung mournful accompaniment to a battle of puppets. Mimes and acrobats meandered through the crowd, delighting the children. The wrinkled green giant sniffed poinsettias, fluttering from flower to flower with elephantine grace. The dog strolled on its hind legs like a dappled Louis XIV.

In the third minute of the show the Guardia Civil arrived and, making a display of fiddling with their holsters, arrested the entire troupe. The accordion gave a last, sardonic wheeze as the group was led to jail, the crowd emitting unhappy whistles, the green giant still skipping and sniffing poinsettias. The Guardia’s patent-leather hats, like the ears on corpulent Disney mice, bobbed at the edges of the troupe, curiously in context.

The crowd remained in the Square for a few minutes, grumbling its displeasure to itself. Everyone loves a juggler and a clown. The Virgin Mary herself, someone said, had sanctified them with a miracle long ago.

But there was nothing to be done. One could not reason with the Guardia who are, after all, foreigners from the Mainland. They do not, someone remarked, even speak the local language (Ibicenco). So the crowd muttered, and shrugged, and went away.

In the police station, the troupe submitted to a search for drugs, produced their passports, and acted with great seriousness.

Did they realize they could be charged with wearing masks in public?

No. Is that a crime?

Of course.

What mask?

The green head with the red horns. It makes a fine disguise. This is a punishable offence.

Oh.

Did they realize that they must cut their hair or be deported?

No.

Yes, this too is so. One cannot tell the women from the men.

Oh.

What is their reason for being in Spain?

To work.

And what sort of work did they do?

Comedy, clowning….

Did they have a license to clown?

No.

That too is a punishable offence.

Fortunately for the troupe, the Guardia did not press charges, assuring itself that the public order would be preserved if the group would simply get out of town. Which they did. And get hair-cuts. Which they didn’t.

SNIF! (the word is not an acronym, but an expletive found in French comics) is not Ibiza’s strangest commune. But it is certainly the island’s funniest and, probably, its most creative.

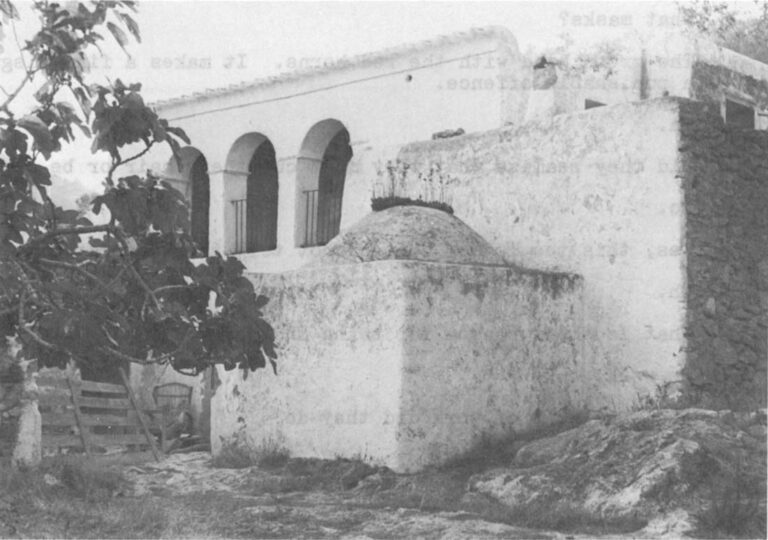

To find it, one must go to the island’s remotest part, a wild, mountainousplace where gnarled pines and blinking goats take lonely advantage of Ibiza’s stony soil. Atop a rumpled mountain overlooking the village of Portinatx and the Mediterranean Sea, invisible from the road below, is the SNIF! finca: a centuries-old manor house enclosing a simple courtyard that commands a spectacular view.

In residence are:

Isabelle — “You know, just Isabelle” — an insouciant brunette who tends to cartwheel;

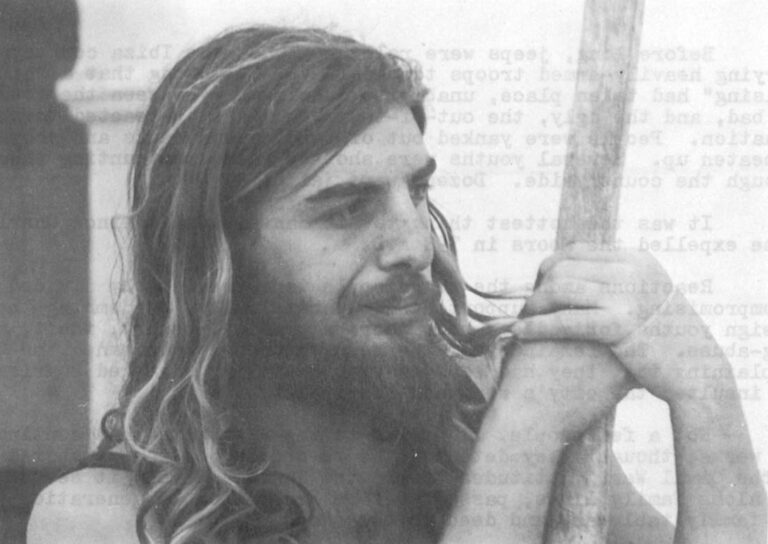

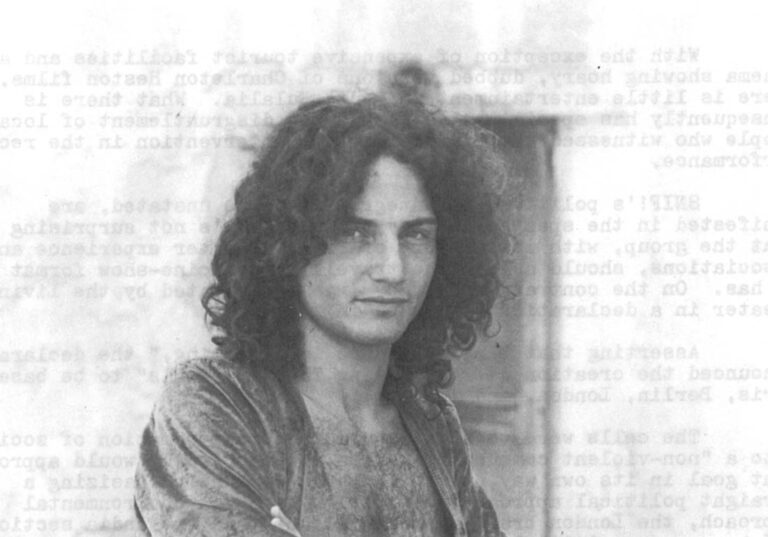

Ricardo Mosner, a young Argentine of prodigious talents and a Renaissance bent;

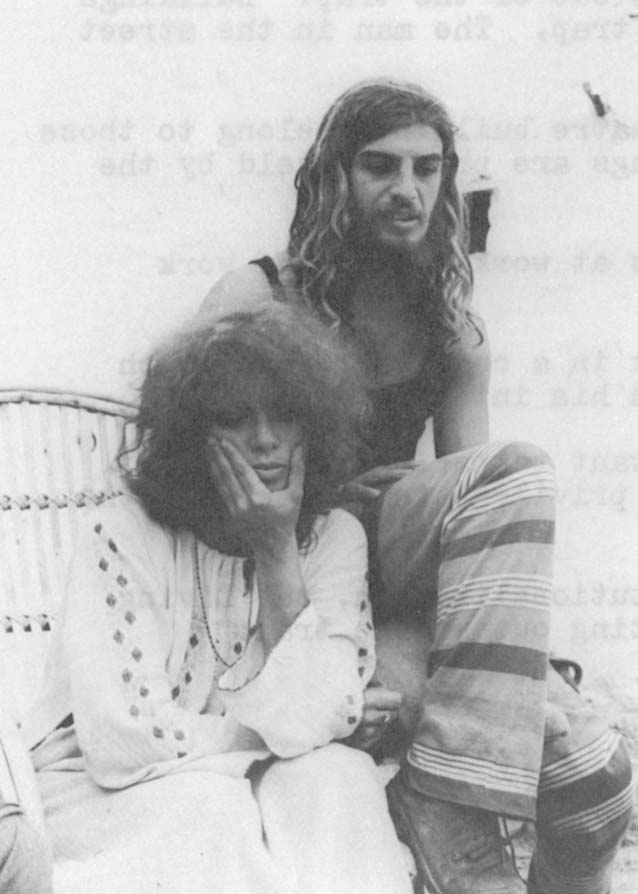

Elisabeth Wiener, a henna-haired French beauty, prospective mother of Mosner’s child, and veteran of more than a dozen French films;

Elisabeth Wiener, Mosner, and friend.

Victor Kesselman, an Argentine cinematographer;

Phillippe Bruneau de la Salle, an elongated Frenchman whose natural reserve and imperial demeanor often cast him in the role of puppeteering “heavy”;

Claire Naaleau, French, and, like Isabelle and Phillippe, a sometime part of the legendary, picaresque Living Theater;

and last, and probably least: The Dog, a friendly nudnik with a penchant for macaroons and low comedy.

Somehow, especially when they go into their act, it seems as if there are twice as many as there actually are.

Communes abound in profusion on Ibiza, as indeed they do almost anywhere that young people gather.

Some are organized according to religious or political positions. Others evolve around life-styles dictated by the members’ shared interest: macrobiotics, nudity, psychotherapy, handicrafts, LSD — whatever activity is likely to be most easily furthered in a closed group.

Other communes simply happen.

It was, in fact, a commune of this last sort that indirectly caused SNIF! its hassle with the Santa Eulalia branch of the Guardia civil.

That was the Commune-Which-Couldn’t-Say-No.

Not too much is known about the group. According to long-time Ibiza residents who witnessed what has come to be called “the incident,” a few friends rented a farmhouse outside Santa Eulalia last year. Apparently the tenants were keen hosts because, before long, an estimated 130 people were camping in, on, and around the house. (While this is an extreme example, such occurences aren’t that unusual; Ibiza is glutted with tourists, short of hotel space, and jammed with “youth tourists” who are typically as short on money as they are long on hair. Crash-pads abound under the euphemism of “communes.”)

Not too much is known about the group. According to long-time Ibiza residents who witnessed what has come to be called “the incident,” a few friends rented a farmhouse outside Santa Eulalia last year. Apparently the tenants were keen hosts because, before long, an estimated 130 people were camping in, on, and around the house. (While this is an extreme example, such occurences aren’t that unusual; Ibiza is glutted with tourists, short of hotel space, and jammed with “youth tourists” who are typically as short on money as they are long on hair. Crash-pads abound under the euphemism of “communes.”)

The farmer who’d rented the house visited his tenants one day and reportedly expressed alarm at the unexpected population density, the apparent deterioration of his property, and the threat to the (admittedly primitive) sewage system.

Brooking no argument, he promptly evicted the tenants, offering only a few hours notice.

Believing themselves victimized by an oppressive landlord, the occupants of the farmhouse immediately marched into Santa Eulalia, chanting, singing, and complaining that there was no place for them to go (as indeed there wasn’t).

By all reports the “demonstration” was closer to a celebration than to a concerted act of civil disruption. But Santa Eulalia is a relatively sleepy town. Someone took umbrage when one of the evicted began an impromptu dance with a Spanish matron. Blows were exchanged. The Guardia Civil was summoned.

Deeming themselves inadequate to handle the large number of demonstrators, the local contingent of the Guardia sent for reinforcements from the island’s capital city.

Before long, jeeps were rolling across the Ibiza countryside carrying heavily-armed troops to the fray. Believing that a “hippie uprising” had taken place, unable to distinguish between the good, the bad, and the ugly, the out-of-town Guardia over-reacted to the situation. People were yanked out of bars, restaurants and shops to be beaten up. Several youths were shot by guardsmen hunting them through the countryside. Dozens were jailed.

It was the hottest thing to hit Santa Eulalia since Charlemagne expelled the Moors in 798 A.D.

Reactions among the townspeople were predictably divided and uncompromising. Many supported the Guardia fully, condemning the foreign youths for godless behaviour, amorality, penury, theft, and drug-abuse. The remainder of the town vigorously condemned the Guardia, complaining that they had behaved with brutality, damaged tourism, and insulted the city’s renowned hospitality.

Not a few people, listening to the arguments that continued for weeks, thought they detected the re-opening of wounds sustained in the Civil War. Attitudes toward the Guardia Civil, it seems, often run along family lines, passed on from generation to generation with the family tableware and deed to the ranch.

It was into this nexus of hostility and bad vibes that SNIF! stepped when the collective made its first and last appearance in Santa Eulalia. What seemed audacious, however, was only innocence.

“We’d been here for awhile,” Victor Kesselman says, “and we thought, ‘Hey, let’s do a performance in Santa Eulalia.’ We didn’t know about last year’s riot. It seemed like a good idea.”

“It wasn’t a bad thing,” Mosner interjects. “The police just became part of the show. It was good theater, with both the audience and the actors fully involved. You can’t contrive that. It has to be accidental, spontaneous.”

Prudence, however, rules out a repeat performance in the same town. Instead, SNIF! puts the show on the road, taking it at random intervals to any of Ibiza’s more than 20 beaches.

“We pass the hat,” Elisabeth says, “and people are usually generous. But the beaches aren’t really a very good place for that sort of thing. I mean, everyone’s in bathing suits or naked — they hardly ever have money with them.”

Nevertheless, enough is collected to pay for the rent and the food, the commune’s only major expenses.

“For awhile,” Victor explains, “Elisabeth paid for everything. It was easy for her; whenever we needed money, she’d just make a film, and it would come. But it wasn’t a good way to do things. Now, there’s less money, but more equality. We relate better this way, and we work harder.” He pauses and smiles. “We have to,” he adds.

Daily life at SNIF! is as serene and playful as one could expect in a commune of clowns. The wild, isolated countryside, and the easy privacy afforded by the rambling, inexpensive villa allow extremes to flourish in comfortable proximity. In one room, Phillippe is reading. In another, Victor is making puppets of papier-mache. Upstairs, Claire is sleeping while Elisabeth plays accordion in the courtyard. Mosner is sketching the bizarre fantasies that teem in his brain. Two Argentine friends discuss Gurdjieff as they float past one another on swings. The Dog is rifling the cookie jar beside the well, periodically turning a quizzical look at Isabelle as she somersaults down the road.

Courtyard at SNIF! headquarters.

Later, Mosner will don the green giant’s head for an hour of mock hitchhiking.

Formerly, a monkey, brought by Isabelle from Barcelona, held court in an enclosed solarium (replete with wading pool and furry totem) beside the house. But, Victor says, “It was filled with hostility. It ran off into the forest.”

“Without working,” Mosner adds.

Because the performances are without scripts and therefore unrehearsed, the line between theater and life is blurred. Somewhere at SNIF!, someone is always “on.”

“We’d like,” Mosner says, “to synthesize our politics and aesthetics. But we have no rules, no scripts. We are what we do.”

“What we eat,” says Victor.

“What we show,” corrects Elisabeth.

“What we seem,” Isabelle comments.

“We want to get better at whatever it is that we are by getting better at what we do. There’s no message,” Mosner concludes with a grin.

Indeed there isn’t. While most of the SNIF! people have relatively concrete political opinions, there is no overt politicking in the shows themselves.

Which isn’t to say that the shows are apolitical: on the contrary. What SNIF! does, and does very well, is to present a wry and innocent perspective whose twin foci are mutual aid and spontaneity. It is no accident that authoritarian figures bear the brunt of their humor. Moreover, working outside the conventional theater, working outside work, SNIF! weaves labor and play into a life-style whose very example is a forceful rebuttal to some institutions which people are asked to accept without questioning.

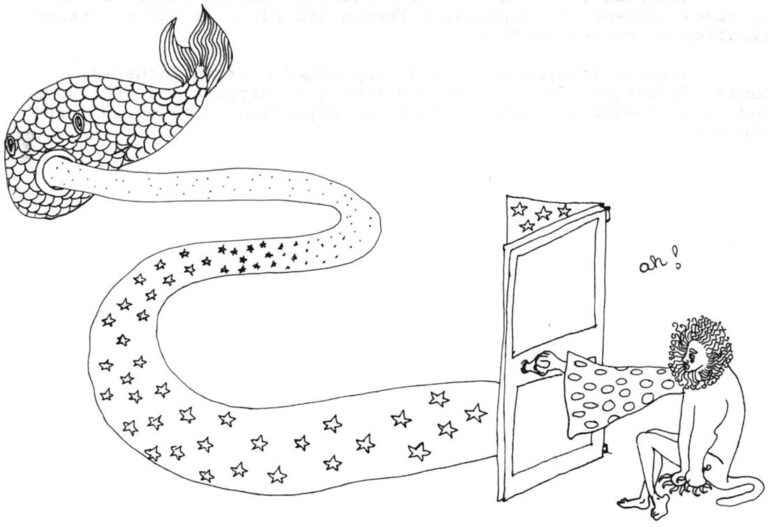

Further, SNIF! realizes as fabulists have since the time of Aesop that humorists (clowns, puppets, and animals) have a freedom of speech that is guaranteed, not by fragile human laws, but by human nature itself. To arrest a clown is to seem both a bully and a fool, a spoilsport whose comeuppance must someday arrive.

Children watching SNIF! perform in Santa Eulalia are unlikely to have been mollified by any explanations of why the police stopped the performance. Similarly, it’s equally unlikely that the average Spaniard-in-the-street was pleased by the sudden end to the free show.

Children watching SNIF! perform in Santa Eulalia are unlikely to have been mollified by any explanations of why the police stopped the performance. Similarly, it’s equally unlikely that the average Spaniard-in-the-street was pleased by the sudden end to the free show.

With the exception of expensive tourist facilities and a cinema showing hoary, dubbed versions of Charleton Heston films, there is little entertainment in Santa Eulalia. What there is consequently has special value. Thus the disgruntlement of local people who witnessed the Guardia Civil’s intervention in the recent performance.

SNIF!’s politics, so integral as to be unstated, are manifested in the spectacles they produce. It’s not surprising that the group, with its history of Living Theater experience and associations, should assume the travelling medicine-show format that it has. On the contrary, that form was anticipated by the Living Theater in a declaration it issued in 1970.

Asserting that “The structure is crumbling,” the declaration announced the creation of four Living Theater “cells” to be based in Paris, Berlin, London, and India.

The cells were to work toward the transformation of society into a “non-violent communal organism.” Each “cell” would approach that goal in its own way, with the Paris commune emphasizing a straight political approach, the Berlin group an environmental approach, the London branch a cultural one, and the India section relying on spiritual tactics.

In its declaration, the organization said:

“Our purpose is to lend support to all the forces of liberation. But first we have to get out of the trap. Buildings called theaters are an architectural trap. The man in the street will never enter such a building:

“Because he can’t; the theatre buildings belong to those who can afford to get in; all buildings are property held by the Establishment by force of arms.

“Because the life he leads at work and out of work exhausts him.

“Because inside they speak in a code of things which are neither interesting to him nor in his interest.

“The Living Theatre doesn’t want to perform for the privileged-elite anymore because all privilege is violence to the underprivileged.”

Complaining of its own institutionalization, the Living Theater prescribed a remedy for “getting out of the trap.”

“Liberate yourself as much as possible from dependence on the established economic system. A small group can survive with cunning and daring. It is now for each cell to find means of surviving without becoming a consumer product.

“Abandon the theatres. Create other circumstances for theatre for the man in the street. Create circumstances that will lead to action which is the highest form of theatre we know.

“Find new forms. Smash the art barrier. We only need art if it can tell the truth so that it can become clear to everyone what has to be done and how to do it.”

There is little doubt but that the members of SNIF! would blanch at being associated with the East-Is-Red prose of the Living Theater declaration. It is didactic and flamboyantly patronizing, totalitarian almost (“We only need art if…etc.”).

It’s not at all SNIF!’s style. Nevertheless, it is within the framework proposed in the declaration that SNIF! has chosen to work. Getting rid of the confinement imposed by the traditional theater, stepping outside the conventional economy for their support, and creating entertainment for the man in the street, SNIF! seems determined to “smash the art barrier.”

Just where that event will take place is unclear. But it won’t happen in Spain.

“Before we came to Ibiza,” Mosner says, “we travelled through a lot of very small towns in Spain, playing in the city squares. Like an American medicine-show, or a gypsy caravan. But everywhere — “

“The audiences are dull. It’s as if they were enclosed in shells,” says Elisabeth. “They’re so restrained.”

Where will they go then?

“To Chile,” Mosner says, “or San Francisco.”

The differences implicit in the alternatives seem jarring at first, but one encounters the same or similar alternatives proposed by young travellers everywhere in Europe.

South America seems to have a particularly exotic hold on much of young Europe’s imagination. Its vast size, remote location, political fragilities, and developmental extremes are alluring to large numbers of young people who are bored with Europe’s sophistication, Asia’s spirituality, and Africa’s dope. To many, South America has the quality of a last, unexplored frontier.

The United States tends to appeal on different grounds.

“It is,” the refrain goes, “where it’s happening.” (This is usually followed by a disclaimer such as “…whether we like it or not.”) Increasingly, a prolonged visit to the United States is as important to the contemporary European youth’s education as a tour of France was to a 19th Century aristocrat.

Mosner, of course, is an Argentine and his reasons for wanting to visit Chile are not necessarily those of the average traveller. Still, his alternative choices are the same ones espoused by many of his contemporaries.

Regardless of where SNIF! goes, or what shape its entertainments eventually take, it is almost certain to continue along the path it currently follows: a quest for a life-style that integrates politics and art without compromising either.

On the surface, that path seems identical to the one followed by many American communards who seek similar ends in their “return to the land.” In fact, however, the two paths are widely divergent. SNIF! emphasizes the element of play in self-realization, while American communes generally place an almost Puritanical emphasis upon hard work. SNIF’s sojourn in the countryside of Ibiza is one of temporary convenience — they’d be equally at home in a city — while American communes are usually steeped in a pastoral mystique. Similarly, American communards place an emphasis upon “roots,” permanence of place, and a tie to the land that European youths often find incomprehensible or, worse, sentimental. And, while the American communard keeps a sharp eye on productivity (of crops or handicrafts), his European counter-part is likely to judge his group’s success by less tangible measures. In so far as these generalizations hold true (and they are violated everywhere), it can be said that groups like SNIF! are engaged with society and its future, while those who “return to the land” are comparitively closed and looking backward.

The distinction between the two kinds of communes is one between an alternative culture (represented by the back-to-the-land movement) seeking detente with the larger society, and a counter-culture (represented by SNIF!) on the attack. One is passive and the other is aggressive. That difference may be at the heart of youth’s complex dilemma: to co-opt, or be co-opted? That is the question.

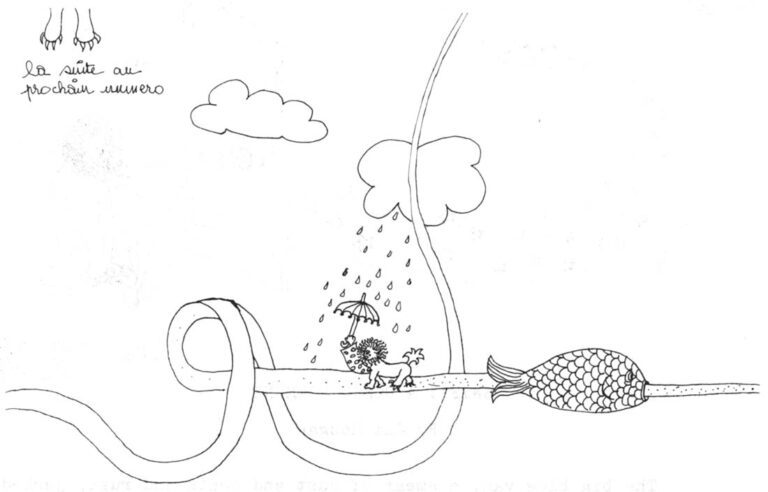

NOTE: The drawings were made by Ricardo Mosner and are used with his permission.

Received in New York on October 5, 1972

©1972 Jim Hougan

Jim Hougan is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wis.). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Hougan, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.