In June of 1996, Kathi Loughlin’s phone rang at work. It was her child’s nanny, and she was frantic. “Something is going on here, you need to come home,” the nanny said, a note of panic in her voice. Loughlin had trouble understanding what exactly was happening on their quiet street in Washington’s Spring Valley neighborhood. “Men in space suits,” the nanny said. “I’m just going to get out of here, I’m going to take the baby out of here.”

“Just stay home,” Loughlin told her. “I’ll come home right now.” She sped to the house in her car. When she turned onto Glenbrook Road and drove up to her family’s brick colonial home, she was stunned at the sight that greeted her. Trucks clogged the street, and about a half-dozen figures in white suits, gloves and boots teemed around her driveway. Breathing through masks, they were unloading equipment and putting up street barriers to prepare for some kind of work at their neighbor’s house, the residence for the president of nearby American University.

Loughlin pulled into the driveway and asked the men if her family was in danger or should evacuate. As she spoke to them, she was acutely aware that she was completely unprotected, while safety gear bundled the crew head to toe. But there was nothing to worry about, the men assured her. They were there to remove some glassware in the soil next door. Nothing to worry about. Loughlin told the nanny not to be concerned, they were just doing some cleanup. But to be on the safe side, maybe they should bring the baby to a friend’s house. Just to be sure.

Spring Valley was a safe neighborhood, the place where Loughlin and her husband Tom had found their dream home two years earlier. The men in space suits were there for a few days, sifting through the soil. And then they were gone. The quiet, peaceful life on Glenbrook Road resumed.

Afterward, the Loughlins puzzled over the incident. The university president had told them about buried glassware on the property, but they hadn’t expected anything as drastic as the crew in hazmat suits. Bemused, they decided the university was just being overly cautious. Sure, munitions and chemical warfare agents had been found on the far side of Spring Valley a few years before, but the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had reviewed the entire neighborhood and announced there was nothing more to find.

“We’re not connecting any dots at this point,” Tom Loughlin told me. “We’re not asking questions about chemical warfare material.”

*

For decades, families like the Loughlins moved to Spring Valley in search of a bucolic existence, a world apart from Washington’s urban neighborhoods. Not long before the Loughlins arrived, though, a long-buried legacy of the neighborhood had resurfaced. In 1993, a contractor digging in a newer area of Spring Valley called 52nd Court had scooped up long-buried World War I munitions containing chemical weapons agents, inadvertently uncovering a toxic heritage that, in time, would undo the Loughlin’s dream.

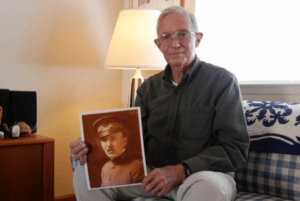

When I interviewed the Loughlins in winter of 2013, it had been almost 20 years since they moved to Spring Valley. They have rarely spoken at length about their experience. Tom, now 58, is tall and genial, a successful financial accountant with a circumspect, steady demeanor. Kathi, who is 57, is a diminutive fireball of energy. A public relations consultant, she is still filled with fury and indignation over what happened to their family.

They were reluctant to speak with me. Spring Valley was, for them, synonymous with a period filled with uncertainty and upheaval, a near-lethal brush with cancer, and a court fight that dragged for years. They had closed that chapter, and were reluctant to reopen it. Still, they agreed to the interviews, hoping that more examination might shed new light on what happened in Spring Valley, and how they came to live atop a chemical weapons disposal pit that is still being cleaned up today.

“You might say, when it happened in 1917 or 1918, what did they know?” Kathi Loughlin said to as we sat in the living room of their current home. “I don’t have any trouble with the guys back in 1917 or 1918. I have problems with the people since then who knew it was there. It’s very disheartening to me.”

*

Tom and Kathi Loughlin found their dream home in 1994. The young couple had been at other open houses in Washington, DC, that Sunday morning, but the house on Glenbrook Road was different. In the octagonal foyer, a real estate agent gave them a flier. It was more than 7,000 square feet, with four bedrooms — five if you counted the basement nanny suite. Four fireplaces. A two-car garage. All on more than a quarter acre of land.

Kathi, who was about eight months pregnant with their first child, felt as though she was floating on air. They wandered through the house, staring up at the coffered ceilings and the custom-milled paneling in the library. Sunlight spilled through the windows of the two-story great room. Brass fixtures glinted in the bathroom. She felt like Cinderella, and her prince had just taken her to his castle. And what a neighborhood Spring Valley was, this quiet oasis far from a shaky part of downtown where they brushed past prostitutes and junkies to get to their front door. This was idyllic, they agreed. It was perfect.

Other couples came and left. The Loughlins stayed the entire open house, discussing if they could afford it, and whether they could close with just a month before the baby’s due date. They were giddy with excitement. The builder, a man named Lawrence Brandt, came to talk with them. They liked the appearance of the nearly identical house next door, but Brandt insisted that this house, 4825 Glenbrook Road, was better for them. They put in an offer. Kathi left on a work trip, her last before the baby was born. While she was gone, Tom called. The offer had been accepted. She celebrated with a tiny sip of champagne.

At the closing, they were surprised to find Brandt there, too. Gathered around the granite-topped island in the kitchen, the Loughlins listened uneasily as the builder told them that a banned chemical herbicide had turned up in the soil during construction. But he assured them that all the tainted soil had been removed. He was disclosing this, he said, because he was a parent himself, and a grandfather. He felt he had an obligation to tell them as they began their family.

The Loughlins weren’t sure what to make of it. It was troubling, but he was so genial and earnest that they felt they could trust him. Still, they decided to split the cost of testing for the chemical. The results came back negative. The closing moved ahead again, but not before Kathi and Tom asked for an addendum to the purchase and sale agreement. A buy-back clause that they could exercise if contamination was found. Just in case. The Army, after all, was going door to door in Spring Valley asking for soil samples. They were testing for contamination. Something about Spring Valley in World War I. Something about chemical weapons.

*

Before World War I, Washington’s Northwest Heights were mostly farms and country retreats for wealthy Washingtonians. The banker Charles Glover had his country manse off Massachusetts Avenue. Former U.S. Senator Nathan Scott kept a weekend home nearby. Trees dotted tracts of land hitched together with rambling country roads. At the center was American University, a struggling Methodist school with grand aspirations but an anemic endowment.

Shortly after the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917, the university offered its campus rent-free to the government. The U.S. Army used the eastern end of campus as a training camp for soldiers shipping off to Europe. The west end of the campus had another, more mysterious purpose. Explosions boomed across the hillsides. Noxious odors wafted from the hill, sometimes drifting to more densely settled parts of the city. Hundreds of scientists in uniform rode the trolley cars to the university gates every morning. Barbed wire fences and warning signs sprang up, caging off the properties that the government leased from landowners.

After the war, the story came out: American University and the land around it had been used as a chemical weapons research station, a proving ground for developing and testing new wartime technologies. More than 100 buildings had been thrown up on the campus and the land around it. Scientists exploded grenades and smoke bombs, and detonated gas shells next to tethered goats and dogs, to see how long it took the animals to die. Artillery shells launched over the fields, blossoming into plumes of smoke and gas. Chemists brewed new poison gases in outdoor stills, including a new chemical agent called “lewisite.” Believed to be so potent that only a few drops were deadly, it was dubbed “the dew of death.”

The land around American University was so idyllic that even Army officials argued that its use for chemical weapons shouldn’t continue after the war. And so with the armistice, the campus buildings reverted to American University. Temporary buildings were torn down or sold (at least one burned down), and the government ended leases with landowners. Very little is known about what happened to the chemicals and munitions at the station. One article in The Courier, the university newspaper, hinted that ordnance was simply buried.

“The munitions were taken back to the limit of the University acres and there buried in a pit that was digged (sic) for them. Would that it were as deep as the cellar of Pluto and Proserpine. Requiescat in pace,” the article read.

A development company, the W.C. and A.N. Miller Co., bought up properties around the campus, subdivided them, and began building lavish homes. The Miller Boys, as they were known, marketed Spring Valley for Washington’s elite. “An exclusive community in the National Capital dedicated to residence of those socially and officially prominent,” one of the Miller brochures boasted.

In an era before the U.S. Supreme Court deemed racial covenants illegal, not just anyone could live in Spring Valley. “No part of the land hereby conveyed shall ever be used, or occupied by, or sold, demised, transferred, conveyed upon, or in trust for, leased or rented, or given, to negroes, or any person or persons of negro blood or extraction, or to any person of the Semitic race, blood or origin, which racial description shall be deemed to include Armenians, Jews, Hebrews, Persians, and Syrians,” read one deed from 1935.

The deeds gave the Millers tight control of the properties even after a sale. Houses could not be altered or fences erected without approval. Homeowners were forbidden from re-grading their properties. And the deeds gave the Miller Co. the right to enter Spring Valley properties at any time to remove items deemed to violate the deeds.

Whether the company ever exercised those expansive legal rights to remove anything from private homes — whether munitions, chemical warfare material or anything else — is unknown. At least one record indicates that new homeowners in the area found remnants of the wartime history. In a 1939 Washington Post article, a homeowner who moved to adjoining American University Park in 1925 “found shell holes and dugouts used for the storing of explosives all over the place.”

Robert R. Miller, the chief executive officer of the W.C. and A.N. Miller Co., did not respond to a recent phone message or email seeking comment.

The development of Spring Valley, as well as nearby Wesley Heights and American University Park, quickly spread. But two Spring Valley lots owned by the university, 4825 and 4835 Glenbrook Road, remained untouched even as the rest of neighborhood boomed. Eventually, that changed. In 1990, American University sold the properties and Glenbrook Limited Partnership, a business entity established by Brandt, bought the lots to build on.

Amid the construction, workers uncovered old laboratory equipment, and dug up a buried 55-gallon drum. Some experienced physical reactions requiring emergency hospital care, according to court documents. Still, by spring of 1994, the houses were ready for market, just when the Loughlins were looking for a new home. Before the property changed hands, the Army Corps of Engineers had collected soil samples on the property in March of 1994, and the EPA had collected its own samples a few days later. The Loughlins say they were never told of the tests or the results until years later.

*

The house was half-empty. The Loughlins had barely any furniture to fill it, and little time before the baby came. The pictures stayed packed. No rugs on the floor. The exception was the nursery, which they had painted with clouds, as if the room was bobbing in the sky. The baby, Nora, arrived in early May.

Life was good for the Loughlins. Both Tom and Kathi had grown up in working-class families in Connecticut — Tom had shared a bedroom with four brothers — and they felt fortunate to have been so successful. Now they had a house so big they scarcely knew what to do so it, with a baby girl in a nursery of her own and bedrooms to spare.

Slowly, they filled the house. They held charity fundraisers for arts organizations and dinners for co-workers. They hired a landscaper, who insisted on planting a tree for their daughter. When their second daughter, Hannah, was born, the landscaper planted a tree for her, too, close to the property line that lay between them and the South Korean ambassador’s residence next door. They hired a nanny who doted on the children and lived in the basement suite.

Everything was perfect. Still, there were episodes that, years later, Tom and Kathi wondered about. A few times each year, the nanny insisted that they sniff the basement air, to see if they smelled anything strange. When Nora helped to plant tulips in the yard, her hands developed an angry red rash. A doctor attributed it to sensitive skin. He prescribed a skin cream, and the rash went away.

Around June of 1996, their next-door neighbor came over with a flier. The neighbor wasn’t just anyone — he was the president of American University, living in the nearly identical residence that the Loughlins had eyed at the open house. Standing on the stoop, he told them a landscaper had dug up some glassware. There would be some cleanup. A team would come to take care of it.

Soon after, Kathi got the call from the nanny about the men in space suits.

They were like, ‘there’s this little thing, and we’re just getting rid of the glassware,'” Kathi recalled. What had happened at 4835 Glenbrook Road was more serious than Kathi and Tom knew. A landscaper had been digging a hole when he hit a buried cache of bottles, and some of them broke in the excavation. “A cloud of vapors came up and hit me in the face,” he told Fox News. A rash covered his face. When he went to the hospital, the doctors told him they were burns.

By this time, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had decided that no further action was needed in Spring Valley. The Army’s neighborhood-wide investigation after the emergency in January 1993, when construction workers dug up mortars at 52nd Court, had found no new evidence of contamination or buried chemical weapons elsewhere.

But the new discovery at 4835 Glenbrook Road, as well as the dogged efforts of some city officials and EPA employees, eventually prompted further review from the Army, which focused on the property next to the Loughlins, the South Korean ambassador’s residence. There was also new evidence. Photos had surfaced during the 1993 emergency dating from just after the war. One of the photos showed a young officer named Sgt. Mauer standing over a pit, along with dozens of bottles and canisters called carboys, destined for burial. On the back of the photo, someone had scrawled, “The most feared and respected place in the grounds.” The pit even had its own name, Hades. But where Hades had been dug, no one was entirely sure. In a further irony, it turned out the soldiers had a name for the area where it lay: Death Valley.

*

The headaches had begun in late 1997. Agonizing pain wracked Kathi’s head, but would come and go. Her public relations agency was expanding, and she attributed the headaches to stress. She popped Tylenol and guzzled coffee, which dulled the pain. But the headaches got worse, even during what was supposed to be a relaxing vacation in Florida.

One night, she had a dream that she was falling. Her arms and legs flailed in the bed. The next day, it happened again, this time while she was awake and on her feet. Her arms and legs began moving on their own, as if she was marching in place, and she was unable to stop them. Panic enveloped her. Then the spell passed. She was drenched in sweat. She summoned the nanny and phoned Tom.

Within a day, she was having regular seizures. At the doctor’s office, she lost all spatial sense, unable to touch her own nose. After she went for an EEG, a grim-faced technician said she needed an MRI. When the doctors held up the film, the golf-ball sized tumor was clear. By this time, she had lost the ability to speak as well as the use her right arm, and she burst into tears.

After several days of treatment to reduce the swelling in her brain, an operation removed the tumor successfully. Kathi was in the hospital for a week, then convalesced at home for several more. Their lives resumed a kind of normalcy — for a time. Then, in 1998, neighborhood residents received letters from the Corps telling them an investigation had been launched into the Korean ambassador’s property next door to the Loughlins. At a public meeting in early 1999, there was an enormous neighborhood turnout. The Loughlins, perhaps naively, had not realized how much public attention there was. Reporters and TV cameramen swarmed them, asking questions like, “what’s it like to live in a death zone?”

Soon representatives of the Corps asked for a meeting with the Loughlins. They met at the house. A member of the Army delegation, a man with a ponytail, was almost completely silent; when Kathi Loughlin bluntly asked who he was, he said that he was a lawyer.

The Army wanted permission to come on their property to test the soil as part of its reopened investigation. The Loughlins got their own attorney; he recommended that the Loughlins demand all the information the Army had about their property to date. When the Army produced a memo, it revealed that the earlier soil sampling had found a reading of 241 parts per million of arsenic in one sample, more than 10 times the cleanup threshold of 20 ppm. The reading was so off the charts that the Army had dismissed it as an anomaly.

Preparations began for the investigation next door. Even before it could start, a new discovery erupted. As the Army was preparing for the excavation at the South Korean ambassador’s home, a 75 mm artillery round surfaced just a few inches under the soil. At work, Kathi got another frantic call from the nanny. The men in space suits were back, this time at the door and ordering her and the children out of the house. Kathi and Tom rushed home, bundled up the children and a few belongings, and decamped to a hotel.

*

When I spoke with Tom and Kathi Loughlin, their account of the months that followed were a blur — a jumble of hotels, forgettable apartments, and tense meetings with the Army, punctuated by short-term returns to their home. The containment tent erected at the South Korean ambassador’s residence was inches away from Nora’s bedroom window; the roar of the ventilation system, audible in the Loughlin’s house, was enough to justify their relocation at the Army’s expense.

While the family lived in a corporate apartment, work began next door. Over the course of the eight-month excavation, 299 munitions had been unearthed next door, various glass containers containing chemical warfare agents, almost two dozen metal drums, and other items. The investigation, it seemed, would never end. But in November 1999, it did, and the Loughlins moved back home.

Around that time, the Army revealed to the Loughlins that soil samples had found arsenic high readings on their property far above acceptable levels. They needed to dig on the Loughlin’s property as well. And they had additional news: the burial pit called Hades may have been on their property. For the Loughlins, the house had been heaven. As it turned out, Hades may have been right under their back porch.

Tom and Kathi finally admitted what both had been thinking privately for some time: that they needed to get out of the house. In 2000, they invoked the buy-back agreement in their purchase and sale agreement. Brandt’s business partnership agreed to buy the property back, and later sold it back to American University for $3.525 million.

On the day of the settlement, Tom and Kathi walked through the house one last time. They wandered through the rooms where their daughters had played, where they had planned to live out their lives. Few words passed between them; they were speechless with grief.

Remembering their nanny, who had since left them, Kathi went down into the basement. When she opened a door to one of the shut-up rooms in the suite, she recalled, an overpowering odor of geraniums wafted out, like walking into a greenhouse filled with the flowers. Remembering that the nanny had complained of a strange smell in the basement, she called to Tom and their lawyer to come smell it as well. She didn’t know it then, but the scent of geraniums is the telltale odor of the chemical warfare agent lewisite.

A raft of litigation erupted from the troubles on the property. Among the claims in the Loughlins’ lawsuit was that Kathi’s cancerous tumor was the result of exposure to chemicals at the site, chemicals that should never have been there, and that had been hidden from them. The nanny — who had her own health problems — also sued the federal government, as did the Brandts. American University, which ultimately had to clean up several contaminated locations on the campus, sued the U.S. Army for $86.6 million in damages. In time, the lawsuits were linked together into a single case, which a federal court eventually dismissed.

American University has long claimed to have been a victim of the First World War legacy, too, saying that the school only learned of possible war-time burial in 1986 during campus construction, and has been diligent about disclosing everything known about the war-time uses of the campus. In late 2000, then-University president Benjamin Ladner responded to a critical article in a Washington magazine, saying that suggestions that the school had withheld information about buried munitions and chemicals “patently false.”

“My predecessors and I have worked closely with the Army Corps, the AU community, and our neighbors to share what we know about the impact of the World War I military operations on our campus,” he wrote in a memo to the campus. His successor, Cornelius Kerwin, reiterated those statements in 2009 testimony to a Congressional committee that held a hearing on the cleanup.

In the past, I interviewed officials from American University about Glenbrook Road and the Spring Valley cleanup. For this article, university spokeswoman Camille Lepre declined an interview request and asked instead for written questions. I sent a list of about two dozen, asking — among others — why nothing had been built on the property for so many years when the rest of Spring Valley was being developed, whether the school had any knowledge of contamination or debris on the property, and whether the school had withheld information at any point.

The university’s emailed response addressed a few factual points but didn’t actually answer any the questions I posed. Instead, Lepre referred me to documents the university submitted to Congress and had previously sent to me. “We reviewed your questions and can provide some additional information related to the settlement, but because your questions refer to a legal agreement and events over 20-30 years ago when current staff were not present, it’s not possible for AU to provide answers to all of them,” her note read.

*

On a crisp, late November morning in 2012, a gaggle of reporters fidgeted in the gravel driveway of 4825 Glenbrook Road, along with civic association members and curious neighbors. Officials from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stood in front of an excavator. Dave Morrow, a lanky U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project manager, stepped forward to a podium with the Corps’ castle logo hung in front.

“This is an extremely complicated project,” he said, gripping the sides of the podium. During the two investigations of the property — the first between 2000 and 2002, and the second from 2007 to 2010 — hundreds of pounds of munitions and lab glassware had been removed, he said, and more than 100 tons of contaminated soil carted away. “The selected remedy that we’re now implementing provides the best long-term solution for 4825 Glenbrook Road,” he said. That remedy was to tear down the house, scrape up all the soil underneath, and replace it with clean fill. Whatever remained of Hades would be taken away.

Brenda Barber, the site project manager, went to the podium next. The collar of her wool coat was hiked up against the chill, cinched in place with a scarf. She described how the demolition would proceed, pointing to a property diagram on an easel beside her. Parts of the property with a high probability of finding chemical weapons debris would be cleaned up under a pressurized tent. Low-probably areas would be cleaned up in the open air, she said.

There were questions. A reporter asked why it was important to remove the foundation of the house. The reason, Barber said, was the Mauer pit. She explained about the photo showing Sgt. Mauer burying chemical weapons agents. The pit was probably in the back of the house, near the porch, Barber said. Unless the foundation was removed, there was no way to ensure that the cleanup would be complete.

There were more questions, about what had been known about the property. About disposal of contamination. About who knew what and when. When all the questions were done, the group shuffled down to the street to stand behind barricades. Officers from the corps did one last walk-through of the house. Then the contractor started up the excavator, raised the bucket and turned it to the brick facade. At first, the excavator jaw gently picked at the brick facade. Then, with a roar, the bucket smashed through the window and the wall, into what had been Tom and Kathi Loughlin’s kitchen.

*

The Loughlins don’t think much about their old house. They told me that they avoid the topic at dinner parties and social events, and rarely discuss it with their two daughters, who are now teenagers. There isn’t much humor in the story for them; still, Tom Loughlin joked that “we’re formerly the largest private owners of weapons of mass destruction in U.S. history, but we just didn’t know it.”

Mostly the memories are a source of sadness as well as anger toward the actors today, particularly the Army, which they feel was dismissive of their concerns and more concerned with expediency than safeguarding the public. “You don’t find what you decide not to go looking for,” Tom Loughlin said. “If you’re living on some formerly used defense site somewhere in the United States, and the Army is saying things to you that are reassuring, don’t be reassured. Protect yourself.”

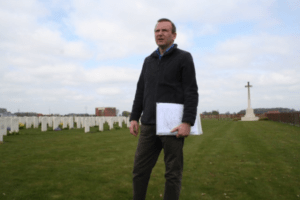

In 2012, Tom Loughlin went back to his old house one more time. It was the day after the demolition had begun. It was a frosty November morning as he pulled his Jeep Cherokee to the curb on Glenbrook Road. He was sweaty from his weekly tennis game, and he needed to get home to shower before work. He detoured through Spring Valley, curious to see the demolition for himself. He rolled down the window and looked across the street at what remained of his dream home.

He wanted to see the before and after. He knew the before. The before had began on that spring day when he and Kathi had walked up the steps for the first time and decided that 4825 Glenbrook Road would be the castle where they would raise their children. Before, there had been a tall shade tree in the front, and hostas planted on the gently sloping lawn. Flowerbeds had covered the grading between the ascending tiers of the lawn.

What a contrast, he thought as he gazed across the street. It was about the same angle as the picture on the flier that they had picked up at the open house in 1994, but half of the house was gone. The flowerbeds and lawn had been hacked up, the soil carted off for testing and burial. The trees long ago cut down. The excavator hulking in the driveway had shorn away the kitchen and dining room, along with the bedrooms and adjoining bathrooms above them. He could see the eviscerated guts of the house hanging out over what had been the driveway. Timbers jutted from under the roof rafters, and PVC piping hung in midair. Insulation showed from under the brick that had been peeled away from the facade. The jagged edge of slate shingles hung in the air. Soon, that would be gone as well.

Loughlin held up his phone and took a photograph through the car window. Then he shook his head, put the Jeep in gear, and drove away.

Today, the house at 4825 Glenbrook Road is gone. So is the pit called Hades. An enormous containment tent sits atop the footprint of the house where day after day, ordnance removal teams have been scraping away the soil. During the week of October 12, 2015, the current cleanup phase ended. In coming days, geologists would confirm that there was no more soil to remove. Then the tent would be moved for the final phase of the cleanup, taking up the garage floor and anything underneath. The whole project would conclude in mid-2017, right around the centennial of the U.S. entering World War I.

I met Brenda Barber at the work site on one of the last days. It was a sunny autumn morning, warm enough for Barber to wear a short-sleeve blouse. She often presents the official face of the Army Corps of Engineers at public events and community meetings; that day, she looked relaxed, wearing jeans and aviator sunglasses perched on top of her head. We walked up the metal steps of the command trailer together, and watched the overhead monitor as the three-member ordnance team in suits sifted through the last bits of soil that had been sealed up under the Loughlins house. “There’s not much to see,” she said apologetically.

In the end, very little had been found at the spot where Hades had been. Some Lewisite-tainted soil, a few artillery rounds, some glassware. Nowhere near the amount that had come out of the property previously. The cleanup phase that included the pit site went so quickly that the teams finished a month early.

Barber said she wasn’t particularly surprised that so little evidence remained of the Maurer pit; the Army had long suspected that its contents had either been spread around the site, or carted away during the home’s construction. Still, the grainy World War I photo had fired Barber’s curiosity. “Personally, looking at the photo and seeing what Sgt. Maurer was doing at that snapshot in time, I wanted to find it. I think what we found were remnants,” she said.

There are still unanswered questions. The Army has an ongoing investigation as to whether there are parties responsible for the contamination other than the Army itself. Lawrence Brandt, the developer, is not aiding the investigation, Barber told me. Back in 2001, Brandt claimed to have disclosed everything he knew about the property, saying “I’m upset because I purchased the property from AU.” A phone message and email to Robert Brandt, Lawrence Brandt’s son, were not returned.

I asked Barber about the Loughlins, and whether they were entitled to be angry. She paused before answering. The Loughlins’ ordeal was before her time, she said, and she has never had interactions with the family. “We were essentially looking for a needle in a haystack, and we had very limited information about where things were actually disposed of, and what was left behind. It was, I think, probably a frustrating experience, but we were doing the best that we could based on the information that we had.”

I pressed her, saying that what happened at the property wasn’t abstract for them — it was their home. She nodded. “I can clearly understand their frustration. I think it was probably a frustration that both parties felt, and wanting to answer their questions and not having the information we needed to give them the answers they were seeking,” she said.

On the overhead monitor, the cleanup crew was rotating out, and another crew coming in to replace them. The radio crackled in the background. I asked her if the Army had any regrets about how things had gone. “We’ve discussed it as a project team, and I think in retrospect, looking back at the history of just this particularly property, there are likely a lot of things that in hindsight we would have done differently,” she said.

@TheoEmery

Theo Emery is researching the origins of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service.