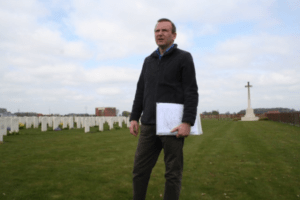

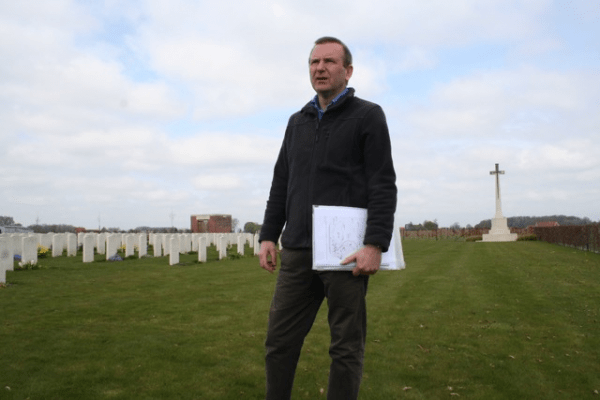

IEPER, Belgium — The breeze blew in from the east as Simon Jones crossed a newly mowed field in Flanders. It was a brisk April morning. He followed a green ribbon of grass that stretched across the pasture and ended at a marble archway. On the other side of a hedge lay rows of marble headstones.

At Jones’ back, the long blades of wind turbines turned slowly in the distance, the towers rising beside a canal not far from where the German lines lay in December of 1915, when clouds of phosgene, an industrial chemical, blew downwind into the British trenches and bunkers where soldiers lay sleeping.

Jones stopped short of the cemetery, one of almost 200 British graveyards from World War I near Ieper, where the Germans battled the allied armies back and forth for four years. Turning to face into the wind, Jones told me that some of the first soldiers ever killed by phosgene were buried here.

“We have a pretty good warning system now in the trenches, these klaxon horns. So in the front line those have sounded, where the troops are still there,” he said. He spoke in the present tense, as if the attack was unfolding around us. “But then, in the canal embankment itself, there’s a lot of troops sleeping in the dugouts. They don’t manage to get word to those men in time, because they’re in these dugouts. They’re asleep. Can’t alert them.”

One of the men who died that day was found with his gas mask on and a bullet wound in his head. An inquiry found that he had likely inhaled the gas before he got his mask on. Terrified of an agonizing death from gas poisoning, Jones said, he probably shot himself in the head.

Jones, a military historian who acted as my guide in Flanders Fields, brought me to the Talana Farm Cemetery on the outskirts of Ieper (or Ypres, in French) on April 22, a notorious date in World War I. Exactly one hundred years earlier, a different attack took place outside Steenstraat, a few miles north of where we stood. On that day, a German Pioneer regiment opened the valves on thousands of tanks of chlorine. Waves of the gas swept over regiments of French colonial troops and reservists, killing scores. Two days later, another attack followed, killing Canadian troops. More attacks were to come.

The chlorine attack, which I wrote about for its centennial, changed the tenor of the war, igniting outrage against the Germans and spurring the British and the other allies to adopt gas as well. The importance of the phosgene attack eight months later might seem less important, a footnote to the gruesome first that chlorine represented.

But the debut of phosgene has another, more subtle significance. When the alarms sounded and clouds of phosgene blew over the English lines, it illustrated the first major escalation of gas warfare and the start of the conflict’s chemical arms race.

Indirectly, that acceleration triggered something else as well: the modern disarmament movement that resulted, almost eight decades later, in the Chemical Weapons Convention that Bashar al-Assad has flouted in Syria, despite having agreed in 2013 to its edicts requiring chemical weapons disarmament.

“With the sporadic use of chemical weapons in Syria from 2012 through 2015, history is repeating itself,” Amy Smithson, a security analyst and expert on chemical and biological disarmament, told me in an interview and reiterated in a later email.

“This hundred-year anniversary is a reminder that it’s not just the so-called classic warfare agents like mustard gas and nerve agents that get used in war, but chemicals that have widespread commercial uses, such as chlorine, phosgene, can also find their way onto the battlefield,” she wrote. “Chemical warfare started in World War I with the use of commercial chemicals.”

The April chlorine attack had come as a surprise, even though the British had received intelligence about the attack beforehand. In the months that followed, the British anticipated an attack with a new gas, though they didn’t know when or what chemical would be used, Jones said. After the chlorine attack, the British had issued its soldiers rudimentary masks — a cloth hood soaked in neutralizing solution.

The British eventually gleaned details of the phosgene attack from the interrogation of a German prisoner, who was persuaded to talk after he was left handcuffed overnight in a freezing attic, Jones told me.

In the early morning of December 19, the British heard clanging and coughing from the direction of the German lines, and concluded that the attack was imminent. The alarms sounded and front-line troops began to evacuate to clear the way for the British artillery barrage that was to come.

The evacuation came too late. The gas cloud arrived while the men were still withdrawing. The men billeted in underground bunkers never even had a chance. In all, there were about 1,000 casualties and 120 men killed, including the four buried near Talana Farm, which was later turned into a Commonwealth cemetery.

Jones took out a map and oriented it to where the front lines would have been. He showed me the positions of the Germans and the British, the communications trenches where the British were frantically withdrawing when the gas alarms sounded. The dugouts where the sleeping English bunked. The site of the farm, where soldiers were billeted and brought for medical care after the attack.

Phosgene, along with its chemical cousin diphosgene, was considered more lethal than chlorine. Jones said its introduction escalated the chemical arms race in several ways. It forced the British to engineer a new gas mask, which soldiers had to wear for long periods and impeded their performance. In addition, phosgene’s higher toxicity made it a candidate for filling artillery shells; with gas shells, chemicals weapons became far more common on the battlefield.

It also created a scramble to manufacture it. The French first used phosgene in shells in spring of 1916, according to Jones, and soon all of the allies were packing it into shells. Chloropicrin, a nausea-inducing agent which was non-lethal, was the next escalation in the race. It penetrated gas mask filters, forcing those who inhaled it to tear off their masks and face exposure to deadlier gases that accompanied it.

Mustard, or dichlorethyl sulfide, unseated all of them in 1917 as the “king of the war gases,” because of its tendency to linger on the battlefield and its gruesome physical effects — blisters, rashes and blindness — that took soldiers out of action for weeks or months.

“Unfortunately, both sides were soon engaging in a tit-for-tat use of commercial chemicals, and when the Germans introduced mustard gas, then the allied countries followed suit. It was an atrocious escalation in the horror war,” Smithson told me.

The United States, after a slow start, began a vigorous war gas program of its own after entering the war in 1917. One of the first U.S. war gas plants was a phosgene factory offered up by a company near Niagara Falls. The hub of the American research program was in Washington, DC, at the American University Experiment Station, a lab where some 1,200 chemists and scientists labored to develop chemical weapons. By November 1918, the Chemical Warfare Service was manufacturing more gas than all of its allies combined and surpassing Germany. Lewisite, a new war gas concocted by American chemists, was ready for mass production in fall of 1918. The war ended, and it was never used.

In the modern era, few dispute that chemical weapons in World War I added a new layer of cruelty and barbarity to an already horrific conflict. But the actual effectiveness of chemical arms has been fiercely debated since its very beginning. Conclusive answers were elusive then and remain so today because countries inflated or deflated statistics about gas casualties when it was advantageous to do so.

Seth Carus, a distinguished research fellow at the National Defense University and former senior advisor for biodefense to the vice president from 2001 to 2003, reviewed statistics on the war’s gas casualty figures. He concluded that the most widely accepted figures of gas casualties and fatalities in the war were deeply flawed. Long-accepted statistics hold that gas produced a million casualties and 91,000 deaths on all sides. The actual numbers are probably far lower, Carus found, more like 600,000 casualties and 33,000 deaths.

Using gas on the battlefield was a “preposterous” way to wage war, he said, yet mythology about its effectiveness has shaped perceptions about chemical weapons ever since. By overinflating the importance of gas in the war, subsequent generations saw it as more effective and a greater threat than it actually posed. That fear was amplified after the war by a nightmare scenario that never actually transpired, at least not right away: aerial gas bombing of cities.

“The disadvantages to chemical weapons were often far greater than their advantages, and that in fact most people didn’t want to use the weapons because they weren’t terribly effective, at least in these operational military settings,” he said.

Jones also takes the view that chemical weapons were not particularly effective in World War I. Far more soldiers were killed with another new weapon in the war: high explosives, or HE, as they were called. Designed to explode on impact, HE killed far more soldiers than gas. Yet gas is considered to be a weapon of mass destruction, while high explosives are not.

“I think if you asked a soldier in 1918 to name a weapon of mass destruction, he’d say, a high explosive shell, number one, and, number two, machine gun,” he said. Gas was used on a mass scale, to be sure, he went on, but the number actually killed is dwarfed by the millions killed by conventional weapons. “So you can’t call it a weapon of mass destruction in the First World War. It just doesn’t make any sense.”

When, then, did chemical weapons morph into a weapon of mass destruction? The use of chemical weapons after World War I did not follow the arc that many predicted. Germany produced vast amounts of gas in World War II — including the new nerve agent tabun — but never used gas on the battlefield as expected in World War II, although gas was used to murder imprisoned Jews. Italy deployed it against Ethiopians, and Egypt reportedly used phosgene against Yemenis in the 1960s, though Egypt denied it.

The turning point was Saddam Hussein’s use of gas in the 1980s against Iran and Iraqi Kurds, setting in motion the Chemical Weapons Convention that went into effect in 1997. At the same time, chemical and biological disarmament became bargaining chips in the intricate politics of nuclear disarmament, creating a kind of false parity among the three, Jones said.

Now the accusations of Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical arms has added a new and troubling dimension to the issue that seemed to have been solved by international consensus. Syria’s deployment of sarin against civilians in 2013 led, with Russia’s brokerage, to al-Assad’s signing of the Chemical Weapons Convention. Now, he is now accused of breaking those pledges with repeated use of chlorine-filled barrel bombs against civilian targets. He denies doing so, but the nature of those attacks leaves little doubt as to which side dropped them.

In a macabre twist of history, al-Assad’s army is now allegedly committing the very acts most feared after World War I — the bombing of civilians from the air. Despite the complicated disarmament apparatus of the convention, he has faced no real consequences for doing so. That, too, has an echo of World War I, in that Germany also had signed pacts forbidding the use of asphyxiating gases on the battlefield, but went on to use them regardless.

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, the group charged with enforcing the Chemical Weapons Convention, has appeared ineffectual in the face of the accusations, unable to muster meaningful action against Syria.

In April, I questioned OPCW Director-General Ahmet Üzümcü about whether Syria’s violations reveal flaws or weakness with the convention. He defended the organization, saying that the destruction of sarin and mustard arsenals was “a big accomplishment.”

In June, he acknowledged in a speech in the Hague that the organization must evolve in order to meet new kinds of threats, saying that the Syria mission “jolted us into enhancing our approach.” The organization also needed to plan for the potential use of chemical weapons by terrorist groups and non-state actors, such as the self-proclaimed Islamic Station, which has also been accused of using chlorine. “Clearly, we don’t need to fix what is not broken. But we will need to do some tinkering, given the challenges ahead,” he said.

Smithson said no treaty is truly foolproof, and that includes the Chemical Weapons Convention. The toughest provisions — called “challenge inspections” — have never been activated, she said, despite suspicions of cheating in Syria and elsewhere. “That failure is one of political will rather than of the treaty’s provisions,” she said.

Now, the self-described Islamic State, also known as ISIS or Daesh, has reportedly used chemical weapons as well. In August, IS fired mortars against Iraqi Kurds containing some form of chemical agent. On August 21, U.S. Marine Corps Brigadier General Kevin J. Killea revealed that preliminary field tests suggested the agent was sulfur mustard, the king of war gases unleashed in World War I. IS had already been accused of earlier using chlorine bombs.

Smithson said that security analysts have long predicted that terrorist groups would adopt chemical weapons; the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo used the nerve agent sarin in two attacks in the mid-1990s. The Chemical Weapons Convention was intended to prevent both states and non-state actors from acquiring or making chemical arms.

Smithson believes it’s unlikely that a new chemical arms race is at hand, because most states long ago gave them up. But groups like ISIS and others find chemicals attractive because they are readily available and their use in relatively small quantities can injure, kill, and terrorize. Still, she said, “conventional bombs and bullets by far remain the favored tools of terrorists.”

In Flanders, my last stop with Jones was a cemetery tucked into the countryside. Dozinghem Military Cemetery was at the end of a dirt road, folded into the woods. A groundskeeper greeted us after we parked. Other than the gardener, the only person we saw was a woman walking a dog. It was quiet and still.

This place too, represented a grim first in the war. In mid-July of 1917, German gas shells began to fall over Ieper, where some British artillery and reserve units were stationed. Some 50,000 shells fell, scattering an oily liquid that had a faint smell of mustard or garlic. It took hours, even as much as a day, for the symptoms to emerge — blisters, blindness, burns. A Brigadier General who passed through a heavily shelled part of the city in his car was hospitalized for two months with burns and blisters.

Dozinghem was where the casualties were taken to two field hospitals. It was here that some of the first men exposed to mustard gas were buried. Almost 800 gas casualties were brought to one of the hospitals, and about 300 to the other. Ninety-five of them died over the days that followed.

Mustard was coveted as a war gas in part because of its debilitating affects, but also because it lingered on the battlefield, poisoning the very ground underfoot and depriving the enemy of territory.

Jones told me that the mustard gas attack on July 12 and 13 was intended to forestall a new British attack after the Battle of Messine Ridge. The attack was delayed, but for reasons completely unrelated to the gas. In other words, even from its first moment, mustard didn’t have its hoped-for effect. Nonetheless, the Germans continued to use it, pounding both battlefields and civilian-filled cities with shells. The allies adopted it as soon as they could unlock the secret of making it. It soon became ubiquitous on the battlefield, a part of the war’s grisly fabric.

As we walked between the rows of graves, Jones reflected on the failed assumptions that brought such a weapon to the battlefield. “They just never behave as they’re supposed to,” Jones mused about chemical weapons in general. “They never do what they’re supposed to.”

@TheoEmery.

Theo Emery is researching the birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service under his Alicia Patterson fellowship.