The ordnance team had been downrange about 20 minutes when the artillery round surfaced. Inside a hanger-sized tent in the Washington, D.C. neighborhood of Spring Valley, an excavator swiveled slowly back and forth, the bucket scooping soil from one pile at the tent’s rear and depositing it in another mound closer to the roll-off container that would haul the dirt away. Sensors sipped the air, testing for traces of chemical weapons agents. Reina Wunschel stood to one side in her Tyvek hazmat suit, watching the soil cascade from the bucket. Toward the back of the tent, another ordnance technician watched the other pile. A third crew member worked the bucket on the excavator. In their suits and masks, it was difficult to tell them apart until Wunschel’s voice crackled over her radio, calling up the hill to the command center.

“Can you zoom in?” she said.

Outside the tent, it was a crisp March morning, with a forecast for afternoon snow. Inside the command trailer, Reina Wunschel’s husband Scott, the site manager for the Army’s cleanup contractor, watched the ordnance crew on an overhead monitor. In the back room, the safety officer toggled the cam, adjusting the view on the three figures. There wasn’t much to see, just the repetitive gyrations of the backhoe and the slow motions of the technicians swaddled in their suits. The coffee machine sputtered out another cup of coffee. A sign tacked to the wall read, “Do not dumb here.” J.R. Martin, the operations officer, wore a sweatshirt with the emblem for his old Army EOD unit — explosive ordnance disposal. He calls ordnance guys like himself “migrant rust farmers.” His daily logbook with the day’s entry, March 3, was in easy reach, but so far there wasn’t much to record. He was describing tree limbs downed in a recent storm when Reina asked for the close-up.

“Go to your right a little bit, Reina,” the safety officer said over the radio.

“Something of interest?” she asked.

“Yeah, it is,” he said.

Amid the banter in the trailer, it took a moment to register that something was happening downrange. The cam zoomed onto the dirt pile. Reina Wunschel knelt down. Everyone in the trailer stared at the screen. There was an object in the dirt. It was long, with a narrow neck at one end, and stubbled with rust. Reina picked it up and cradled it. A 75 mm projectile buried since World War I. Martin looked at me, the reporter in the room. “Leave,” he said. Everybody laughed, but he was only half joking

Downrange is military jargon for a war zone. When soldiers and Marines hugged their families goodbye and deployed for Iraq and Afghanistan, they were going downrange. When artillery companies launch mortars, they explode downrange. Downrange is where shells land and bullets snap overhead. Downrange means UXO — unexploded ordnance.

In Spring Valley, one of Washington’s wealthiest neighborhoods, downrange means the property on Glenbrook Road, where the tent enclosing the excavation is within earshot of the South Korean ambassador’s home. Downrange is where day after day, technicians deployed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers sift through the soil, looking for ordnance, glassware and other chemical weapons artifacts buried on the property at the end of World War I.

For almost a generation now, the Corps has been a disquieting fixture in Spring Valley, the nation’s only neighborhood built atop a chemical weapons proving ground. For more than 10 years, the Glenbrook Road cleanup has been one of the Corps’ priorities in Spring Valley, and many neighborhood residents hoped that when the work concluded there and all of the contamination had been carted away, the Corps would finally pack up for good.

Instead, neighborhood residents have learned that the army’s work is not done. On April 8, the Corps released what it calls a Remedial Investigation Report, a roadmap for Spring Valley’s broader cleanup strategy. Rather than pointing toward a conclusion to the cleanup, as some residents hoped, it indicated that more cleanup may be required on almost 100 properties in Spring Valley. Some are near a possible disposal pit like the one on Glenbrook Road. Others lie within the perimeter of what had been test firing ranges. Some had already been deemed free of chemicals and ordnance.

The revelation that the cleanup may have years to go has been met with bewilderment, dismay and some anger in Spring Valley, where the relationship with the Corps has at times been fraught with distrust. Tom Smith, a member of an advisory board that represents resident’s interests in the cleanup process, told me that he was among those who believed that the end of the Spring Valley saga was approaching, and was astonished when he learned over the winter about the possible new cleanup spots.

“I’ve always thought on an anecdotal basis that there were some homes where, if you looked at the maps and you talk to the people, you sense that there’s probably more there than meets the eye, but you figure, OK, the army has this in hand, they know what they’re doing and all is well with the world. This was kind of a shock to a number of us,” he said. “I know it was a shock to me.”

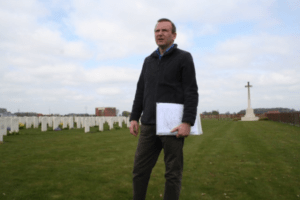

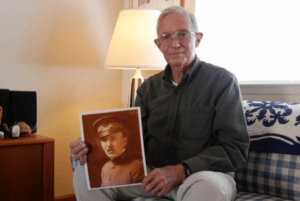

Theo Emery Cutlines: Safety materials and equipment used to gingerly remove and examine aged bombs and chemical weaponry buried under a residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C. Some homes in the upscale neighborhood have had to be vacated or torn down because of the hazards of the century-old weapons disposal site. Photos by Theo Emery.

In January of 1993, a backhoe operator at a home construction site on the northern edge of Spring Valley punched open a gas-filled projectile while digging a sewer trench. The hiss of gas that day turned the neighborhood full of retired civil servants and politicians and ambassadors into a military zone. Ever since, Spring Valley has been what’s known as a Formerly Used Defense Site, a contaminated property that was once under military jurisdiction. In 2013, there were almost 5,000 FUDS in the United States. None of them are quite like Spring Valley.

Before it was a desirable residential zip code, before the properties were bought up by a developer and subdivided and turned into a planned community, Spring Valley was open fields and pastures. The patchwork of properties surrounded American University’s campus, which the school’s board offered to the U.S. government for the duration of World War I.

The eastern side of the campus became a military camp called Camp American University. Later renamed Camp Leach for a deceased officer, engineer regiments trained there before they boarded transports to France. The western side was a top-secret research laboratory and proving ground called the American University Experiment Station. By the war’s end, more than a thousand chemists and scientists streamed through the gates each morning to work on chemical weapons research. They labored to improve gas masks and protective clothing. They tested different shells, the combinations of gas and smoke inside them, how far they went and how they fragmented. There were bomb pits and chemical stills. There was a dog kennel and a goat shed for the animals used in experiments with mustard gas, phosgene and other chemical agents. There were test trenches to simulate those on the front in France. On the edge of the campus, close to the hillside where the Army Corps trailers now sit, was the area where the research division launched shells in a fan stretching westward over the fields.

Mid-way down the hill, in an area forebodingly nicknamed Death Valley, was a pit the soldiers called ‘Hades.’ Shortly after the November 1918 Armistice, soldiers buried jugs and bottles full of chemicals in Hades. The Army learned this after a photograph surfaced of a soldier standing over the pit in a gas mask, apparently in the act of burying the chemicals. “The most feared and respected place in the grounds,” the photo read on the back. For almost seventy years, the property was just an overgrown, empty lot. Then, in the 1990s, a developer built a house atop Hades. The spot where Reina Wunschel cradled the 75 mm round was in the back yard, roughly outside the windows of the great room.

In the fall of 2012, I walked through that room. Ivy snaked through a broken window and clung to the interior wall. I peered through the doors onto the back patio, where a soil sample had come up positive for lewisite, an arsenic-based chemical weapon developed during the way. I trailed my fingers on the dust-covered countertop, and descended into the pitch-black basement with a flashlight. Somewhere in the house, a smoke alarm with a failing battery beeped over and over in a tinny, distant warning.

The Army’s original plan had been to leave the house and clean up around it. Over several years, the cleanup removed more than 500 munitions items, 400 pounds of laboratory glassware and 100 tons of contaminated soil, Then, an intact bottle of arsenic trichloride — one of the toxic ingredients of lewisite — was unearthed in the front of the house. It was a chemical that the Army hadn’t anticipated or planned for, and its discovery raised the question that perhaps the property was just too contaminated for the house to be salvaged. After more study, the Army decided to just take it down.

The day after I walked through the house, an excavator hacked through the upstairs, tearing out electrical wiring and insulation, sending timbers and brick and slate roofing tumbling to the driveway. Within a few days, the house over Hades was gone. Every few months, I returned to check on the progress at the site. With each move of the containment tent, I asked to walk the property, to see the contours of the work, to see what the ordnance team saw when they went to work.

When I went up to the property on the morning of March 3, it had been several months since I had been there. It was the first time I had arranged to watch the cleanup over the video cams. Reina Wunschel was on the second shift. I met her and another UXO technician, a U.S. Air Force veteran named Dan Batt, in the break trailer, where vintage Chemical Corps posters with pictures of cartoon gas masks had been tacked above a window. “Lewisite — smells like Geraniums.” “Mustard Gas — Smells like Garlic.” “Smells like musty hay — phosgene.”

Wunschel had layered up against the cold with a flannel shirt and a white cap pulled down low over her hair. She had flashing eyes and a wide smile, and was coy about how old she was — “a woman never tells her age,” she laughed. “It’s hush-hush.” She had worked in Spring Valley since 2007, during an earlier cleanup phase on Glenbrook Road. Batt, wearing a black Adidas sweatshirt, looked younger than his 34 years. He had been at the property since 2013.

Work in Spring Valley is meticulous and slow. Every step is watched by video. Everything is observed, noted, logged. There are protocols for everything. Some UXO techs don’t like working with chemicals, Batt said. There wasn’t much excitement, as far he’s concerned — a lot of downtime, a lot of monitoring. “Really, it’s very boring,” he said with an easy smile.

There are long stretches where nothing at all comes up. Earlier in the dig, in the phase before the house came down, there had been a lot more. When something does turn up, everyone’s heart starts pumping and the adrenaline flows. “We were finding 75s left and right, ” Wunschel said. “It was more exciting the first time.” Batt had found the last 75 mm shell in February, sealed up behind a retaining wall. That one had liquid inside. Closed shells with liquid are handled especially gingerly, as they might contain chemicals. In this case, it was water.

Those discoveries have been rare recently. Wunschel didn’t mind. She’d been on a cleanup at Camp Sibert in Alabama where she had to sit on a bucket during breaks if she didn’t bring her own chair. She retreated to her truck to stay warm in winter and keep cool in summer. She was willing to put up with the boredom and the monitoring and the extra protocols in Spring Valley. It had a comfortable break room, lots of time off, shift work. “This site here is the Ritz compared to Sibert,” she said.

She wondered if there would be more work in Spring Valley after the Glenbrook Road cleanup ended. She might get her wish, now that the Corps’ remediation report has revealed the more investigation was needed. Letters had gone out to about property owners saying that the Corps needed to return to their properties to check for chemical contamination or sweep for ordnance with metal detectors. The findings were scheduled to be discussed at a neighborhood meeting in a few days, on March 10. The Corps expected a large crowd.

It was about 9:30 a.m. now. The first shift would end soon, and Reina Wunschel’s was about to start. After we talked, she walked down the hill, past the on-site ambulance to the redress tent, where she shrugged into her suit and boots. She passed through the decontamination station, where she put on her mask, a member of her team sealed up her suit, and she hooked up an air bottle to breathe from as she stepped through the tent door, which snapped tightly shut from the air pressure of the ventilation system. Inside, she substituted the bottle for the air hose dangling from the ceiling, picked up a shovel and got to work.

Nothing but dirt for about 15 minutes. Just before the 75 mm shell surfaced, I had asked Reina’s husband, Scott, whether items were overlooked when they first came out of the ground and then spotted later in the pile. “Not too often,” he said. Occasionally that happened with a piece of glass or something that the magnetometer wouldn’t catch. A few seconds later, the shell appeared in the dirt. Chitchat stopped. The mood in the trailer grew tense. Everyone watched the monitor.

“Can we investigate?” Reina Wunschel asked over the radio.

“Yeah, see if you can do a probe,” the safety officer said.

“Copy,” Wunschel said. There was no fuse, which meant the round couldn’t explode, but she needed to know if the cavity inside was open or closed. If it was closed, it could still contain a chemical weapons agent. Or it might contain water. Or nothing at all. She carefully inserted a probe. It went in about four inches and stopped. The shell was closed. Martin got on the phone to the Army Corps headquarters in Baltimore to report that a mortar had been found. “I’m not kidding,” he told the Army site manager.

“Closed cavity. We’re going to pull the team out, send EOD in,” he said.

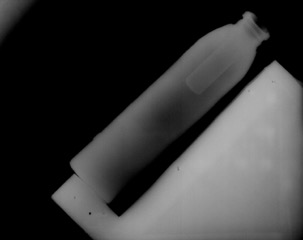

Wunschel used the probe to scrape dirt out of the interior of the round. Then she laid it down on a piece of plastic and snapped pictures. Her work was almost done. When a civilian team finds a projectile, it’s passed off to the military ordnance disposal unit, who come in to X-ray the shell, then pack it up in a special, stainless steel container to be brought off site.

Wunschel gingerly picked up the shell swaddled in the plastic sheet, carried it down the stairs to the tent door, and laid it carefully next to what had been the foundation of the house. Then she sloshed her boots in the shuffle pan beside the door to clean off any contaminants, and left the tent with the two other technicians, leaving the shell on the concrete slab that used to be a basement floor. It would be an hour or so before the EOD team brought in the X-ray to peek inside the round. When they did, it was a ghostly image, the century-old dirt and rust invisible, the cavity within sharp and clearly visible. And empty.

A week later, the X-ray appeared on a projection screen in the basement of the Methodist church up the street from the dig. The occasion was the bi-monthly meeting of the Resident Advisory Board. At the meetings, brisk Army efficiency sometimes collides with civilian skepticism. The Corps had been right to expect a bigger crowd. There were dozens of people in the audience. Extra chairs were carted out.

Brenda Barber, the Army’s stylish manager for the Glenbrook Road site, gave an update. She had done this many times, and moved quickly through the inventory of items discovered downrange during the dig’s latest phase.

Twenty-one truck-sized containers of soil removed. Glassware weighing 13.25 pounds. Three 75 mm rounds and two 4.7-inch projectiles, she said, with the X-ray of the shell Reina found behind her on the screen. No readings for airborne chemical agents. The fence had been replaced. Everything was on schedule, she said. There were no questions for her.

Dan Noble, the project manager for all of Spring Valley, was next. He had a harder job. He had to explain the remediation report and why it was coming out 22 years after the first emergency in Spring Valley. He also had to explain why the Corps now needed to go back to properties it had deemed safe years earlier. He pleaded for civility. “Please be polite. We always try to be polite with each other,” he said. “These issues can arouse concern and tension. But they are what they are.”

On the screen, an overhead slide appeared with an eight-step flow chart of the cleanup process, and he used a laser pointer to show where the Corps was in the process. “We’ve been here since 1993 conducting this process, so it might be a little discouraging to see that we’re — after 22 years — here,” he said. The pointer’s red dot hovered around step three. “I don’t want you to look at this and think, ‘well, they’ve got another 30 years, at least.’ That’s not true. But we’re simply acknowledging that it’s a long process.”

A map of Spring Valley replaced the flow-chart on the screen, showing a cone at its center, with the narrow end on the edge of the American University campus, flaring out as it extended northwest. There was a circle below it. He explained that the cone and the circle were areas that the army needed to investigate further. “There were two static test fire areas that were used in World War I. That’s this triangular area right here –” he pointed to the long cone on the map, “– and this circular area right here.” The cone had been the mortar range, the circle had been static test range in the middle of a circular test trench. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of chemical-filled shells had been fired in the downrange areas where homes now stood.

One homeowner asked why the army needed to return to properties it had already investigated. Another wanted asked about what kinds of shells had been fired, and what toxic payload they contained. A man in the front row was skeptical about the army definitions of risk and hazard. “It sounds like wordsmithing to me,” he said. “It sounds to me like they’re all risks, quite frankly.”

The board’s public health consultant gave a long presentation. The meeting had been going on for over two hours now. It was getting late. Some in the audience were frustrated. Tom Smith, the advisory board member, wondered whether residents in other parts of Spring Valley who had received assurances that their properties were clean might someday be told otherwise. “Here we are, 22 years after this project began, and we’re looking at properties that many people thought were clear,” he said.

The army could always come back, Noble said. “The bottom line with every formerly used defense site is never absolutely forever going to get rid of the military. We’re going to retain responsibility for the site basically forever.”

Inevitably, the questions turned to property values — a common refrain in a neighborhood where homes can sell for millions of dollars. The man in the front row who had complained about the Army’s definition of risk asked whether homeowners would be compensated if their home values fell because of the new investigation. “It’s a quarter-of-a-million-dollar question. A half-a-million-dollar question,” he said.

After some prickly back-and-forth, an advisory board member asked whether the conversation about home values should be held after the meeting. The audience erupted in indignation. “Why would you want to have it behind closed doors? Have it out in public,” the man in the front row snapped. “You have something better you’ve got to do?”

The final question came from a man behind me in a suit and tie. He had spoken with the Army when he bought his home. “There was never any mention about thousands of chemical munitions being unloaded on the property that I bought. Had I known that, I probably would have done some testing,” he said. Would the Army pay for additional testing? he asked.

Noble spoke carefully. “The basic answer is no, you can’t come to the Army and request us to test and we’ll do that. No, we don’t do that,” he said. The Army had worked out risk assessments with the EPA and city regulators, and all of the necessary testing had been done. “The conclusions of the (remediation) report are no, such a risk doesn’t exist, so…” His answer trailed off. A long silence followed.

The board chairman promised that a real estate expert would attend the next gathering. The meeting adjourned. It had gone far later than scheduled. Some residents congregated in the back of the room, next to the maps showing the range fan. Others gathered their coats and gloves and quickly walked out into the rain to their cars, and back to their homes. In the morning, the ordnance crews resumed their work downrange, sifting through the soil. The Corps released its end-of the-week update a few days later. No mortars, no glassware, no chemical weapons debris reported. Nothing but dirt.

Later, Smith told me by phone that he found the whole episode frustrating. In the years following the 1993 discovery, antagonism between the Corps and residents reached its nadir after the Army announced that its work in Spring Valley was complete and then was forced to backtrack on that claim. Smith said he hopes that history isn’t repeating itself.

“I would hope that it’s not gone back to those bad old days, but when you sat in meetings for the better part of two years with the Army talking about how they finished this and they finished that, and the only projects we have left are dealing with the groundwater contamination. And then one day, all of a sudden, we’ve got all these homes that have potential problems with them. It’s bound to make you think ‘what else have you missed?'” Smith said.

Dan Noble acknowledged that what’s underway in Spring Valley is a long process, and could be confounding to people who haven’t followed the story from the beginning. Moreover, he said, he could see why homeowners whose properties had already been cleaned up would be vexed to learn that the Army now needs to return to investigate further. But he said the Corps has done its best to be transparent about the process. “I think we’ve tried to remind people that it’s several steps and that it could lead to additional work.”

Theo Emery is examining the creation of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service during his Patterson fellowship.