On May 10, 1931, the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, as usual, was packed. There was a buzz in the crowd. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., the pastor, was ill. His son, Adam, Jr., would deliver the sermon. The pulpit hardly frightened Adam Junior. He was raised in this church. The women in the audience had known him since he was an infant, saw him take his first step, stocked his room with beautifully-wrapped gifts on special occasions: he was theirs. But some of the older deacons were wary of young Powell. To them he was a bad boy, a whistler in the dark. He had been kicked out of college for spending too much time with girls, had even boasted of it. Even now he was dating a showgirl. Some Sundays he skipped church to go rowing.

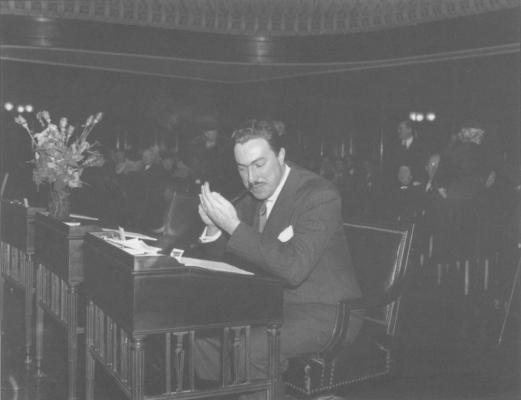

The poet, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, was in the audience that Sunday. After the sermon she rushed a note about the young Powell to a friend. “The boy is handsome, graceful and has marvelous personality and control of the massive congregation. Only 22 or 23. Ordained without any divinity training. But he can handle the people.”

The church sat at 138th street, massive and of Greek design. In the early 1930’s the congregation numbered more than 10,000. There were white-gloved nurses to administer smelling salt to those who fainted during services. Adam Senior was one of the most respected clergymen in America. Harlem was full of religious quacks at the time. Some meant well; all were strange. Father Divine, a short man with a mysterious background, had showed up in Harlem proclaiming himself to be God. He found followers and gave them names like “Wonderful Love” and “Sunshine Bright.” Sufi Hamid positioned himself on Harlem street corners, dressed in storm-trooper garb, and preached about the need to boycott stores that would not hire blacks. Marcus Garvey rode through Harlem streets, in an open convertible, wearing beautiful military attire and a plumed hat, urging blacks to leave America and come to Africa with him. One publication referred to him as a “Jamaican Jackass.” “If I die in Atlanta my work shall then only begin,” Garvey wrote to his followers from the Atlanta federal penitentiary in the winter of 1925. He had been sentenced for mail fraud. President Calvin Coolidge commuted his sentence in 1927, and Garvey sailed away from America, never to be seen in Harlem again.

There was nothing strange about Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. He had credentials. Church members were quick to point out that he was a Yale man. “You know ole man Powell went to Yale, don’t you,” they remind, still to this day. Adam Senior never was a full-time student at Yale. He studied, as an extension student, at the Yale Divinity School in 1895. A degree was never conferred. Still, to the Abyssinian congregation, there was only one Yale, and their minister had been there, and people from Yale did things, important things, got written about in newspapers, led movements.

Adam Senior was a Hoover Republican. The 1929 crash caught him off guard, as it did most Americans. Harlem began a nasty spin into the throes of poverty, far removed in a short time from the sweet music of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance. Adam Senior turned 65 in 1930. The church would have to take on an expanded role in the community. The time had not come for him to step down, for there was still fire in the soul, but it would be prudent to start grooming a successor.

Following a capable stint as business manager of the church, Adam Junior was named assistant pastor in 1932. He would quickly distinguish himself by beginning adult education classes, a nursery, a food line. Daniel Crosby, a Colgate classmate of Adam Junior’s, would remember getting a letter from a friend that said, “Did you hear about Adam, up in Harlem feeding the hungry?” Still, if young Powell dreamed of taking over the church someday, he was going about it in a strange way. In 1933 he became engaged to Isabel Washington, a dancer and actress. The older deacons recoiled, as did his father. Showgirls stayed out late, danced with gangsters, drank gin. Adam Junior knew better. There were veiled threats that his father would not give him money. “Take your money,” Powell said to his father outside the church one day.

As the marriage date grew nearer, Isabel Washington became the most talked about actress on Broadway. She says she and the groom had alternative plans if Powell Senior would not approve of the marriage. They would go on tour. He would give speeches and she would sing afterwards, a kind of on-the-road with Isabel and Adam show. After all, she says, “I was a successful actress when I met him. He was just a low-level preacher.” The idea of a road show was witty, but it never came to that. The couple were married March 15, 1933 in a massive ceremony at the church. “You could not get a taxi in New York,” Isabel Powell recalls. “We had detectives in the audience. Some crazy woman had threatened me.” They honeymooned in Virginia, on a friend’s farm. Then back to Harlem, where the Depression laid like a rug, but not at their doorstep. Powell Senior had amassed a small fortune from real estate; the new bride and groom had no worries. Isabel Powell gave up her show business career, though more than once she thought seriously about an offer from a producer that would put her and her husband on stage as Romeo and Juliet. “Adam finally told me he couldn’t do it. He was just too busy.”

One of Adam Junior’s first public confrontations came against Harlem General Hospital in 1933. It was reported that conditions at the hospital were filthy, and a significant number of the nurses were tubercular. Adam Junior led a throng into City Hall, demanding better conditions. City officials ordered a probe. Conditions would hardly change overnight, but at least it was a beginning. More than 50 percent of Harlemites were out of work in 1933. Misery deepened and strange things happened. On June 21st of that year, a knife-wielding man burst through the doors of the Abyssinian church looking for Adam Junior, who was not there. The man swiped at another pastor, drawing blood. The pastor found a pipe and struck the assailant over the head. The assailant died a week later at Bellevue. The medical report characterized him as “insane.”

Adam Junior’s first foray into politics was a disaster. His father had pulled .strings; to get him a position on the mayoral campaign of Joseph V. McKee, who was running against Fiorello La Guardia. Powell served as Harlem campaign coordinator. He was overwhelmed and outfoxed. He was accused of hogging the spotlight for himself, of turning the McKee movement into “a Powell movement,” as one editorial put it. But if it was a bad experience for the young Powell, says David Licorish, who was on the scene with Powell at the time, he had at least “tasted the good fruit” of political battle.

In his youth, Adam Senior had traveled extensively, around the world and throughout America. He was light-skinned enough to, at a distance, pass for white. He would spy lynch parties being formed in the South. On Sundays he would sermonize about the evils he had seen. He thought travel would be good for his son. Adam Junior was no fool on the road. Once, seated on a train, someone yelled out, “There’s a “n…..” on this train.” “Where?” Powell asked.

One morning Adam Junior arrived on the campus of Virginia Union University to give a speech. Samuel Proctor, a student, was his escort. “I had read a lot about him,” recalls Proctor. On this particular weekend the Powell speech was about “brotherhood and justice and the fallacies of white supremacy. This was before we won any civil rights victories,” says Proctor. “As college students, we were impressed. In the South we didn’t hear many speeches like that.” If Powell elicited praise, there was also suspicion. “He looked so different from black people. They lived in small towns,” Proctor says of the Virginia Union students. “They might of been intimidated by his rhetoric. They could not conceive of a black man who spoke so boldly.”

The travel and the further study at Columbia had begun to position Adam Junior to take over his father’s seat. The older deacons still might object, but they had not figured on the emotional rumbling of youth within the church. At least a third of the congregation by 1935 was under the age of 30. They liked Adam Junior and reasoned that if he hung out with communists, well, that was his business. Olivia Stokes was one of the youthful members of Abyssinian 50 years ago. She walked picket lines with Adam Junior, a trait he had picked up from Sufi Hamid, the man who wore storm trooper attire. Dazzled by Adam Junior’s savvy as she might have been, Stokes would remain, for years, leery of what she referred to as Adam Junior’s lack of “moral leadership.” She thought the differences between Adam Senior and Adam Junior huge. “His father called him to preach,” she says of Adam Junior, “not the lord.”

Strolling from his office to the pulpit, his robe billowing, his strides wonderful, women would say of Adam Junior, “Here comes my lord and master.”

On Oct. 22, 1937, Adam Junior was “unanimously” approved by the deacon board to succeed his father as pastor of Abyssinian. Adam Senior would swear he had nothing to do with the vote. A bevy of city dignitaries would be invited to the event.

“You have taken on great responsibilities here,” a church elder told Powell, now 29 years old. “Preach the gospel and tell the truth If they ask you for your resignation, give it to them and tell them you told them the truth.” During the ceremony the elder Powell grabbed his son, his only child, by the hand, looked him in the eye, and said, simply, “I wish you well.” It was thus predicted that “a new era” had dawned at Abyssinian, that the new pastor, who described himself as a “modernist,” was someone to keep an eye on. The older deacons would consider it their duty to do just that.

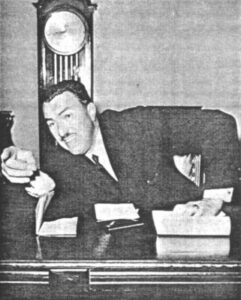

Adam Junior boosted attendance at the church. Parishioners had to be turned away, and he had loudspeakers installed outside so his sermons could be heard. He had allies–Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., Robert Wagner–speak at the church. He challenged those who disagreed with him on anything to come debate him at the church, in full view of the congregation, head to head. Who would walk into a lion’s den? His detractors declined. “What cowards!” Powell would say about them to the congregation. He dashed–headfirst–into community events. He picketed the Amsterdam News with employees of the paper when there were complaints about working conditions. Powell’s tirades became so vehement that the paper decided to do something about him: hire him on staff as columnist. The newspaper trumpeted his arrival: “Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., militant young minister, pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church, and graduate of Colgate University, will join the editorial staff as columnist, delving into social and economic problems. Liberal champion of the lowly and oppressed.”

“Negroes,” Powell wrote in an April 11, 1936 column, “we are at a crossroads. Left or right. Freedom or oppression. Quo Vadis?” From his soapbox Powell campaigned for an anti-lynching law, for jobs, for a boycott of the 1936 Olympics. He was not the only new leader emerging in Harlem. Roy Wilkins had arrived from Minneapolis. He was young and brainy and himself writing columns for the Amsterdam News.

A young opera singer turned union organizer by the name of A. Philip Randolph was there. Many predicted his future bright and said if Harlem ever got itself a Congressman, he would be the perfect choice.

Lloyd Dickens had come to Harlem from Oklahoma, where his father had worked in politics. Dickens was one of the first to envision a political career for Powell. It was Dickens who urged Powell to run for city council in 1940. Dickens remembers that Powell first brushed it away, thought his duties at the church would interfere with a try at politics. Dickens, however, persisted, and Powell was convinced he should run. “People were just wild about him,” says Dickens. Powell picked up endorsements quickly: the American Labor, Fusion and Democratic parties all endorsed him. His Sunday morning sermons became political speeches. Acy Lennon was hired as campaign assistant, a bodyguard, really. Lennon was from North Carolina, a farm boy who weighed 300 pounds. He carried a pistol to protect Powell. Lennon remembers that council campaign as thrilling. “We took the city by storm,” he says. “We had this thing organized. We couldn’t miss. Every day we put out a sign that said ‘Adam Clayton Powell will speak here tonight.’ We had music on the bandwagon. One man on saxophone, one man on clarinet, one man on drums. Just enough to make some noise.” Powell swept to a city council victory, being sworn in by Mayor La Guardia in 1941. He got assignments to committees–building, labor, housing–but city council quickly grew boring. It was a paper pushing job. One could go crazy worrying about garbage and street lights. Furthermore, it was far away from headlines. And now, the headlines were focusing on the fact that a congressional district, the 22nd, was about to be carved out for Harlem.

In 1942, along with three other investors, Powell founded a weekly newspaper, the People’s Voice. It was a kind of Village Voice, artsy and radical and a dime a copy. Powell gave himself a column, his picture above the column, the perfect platform for someone considering a run at high office. “It’s just me,” Powell said once when asked about the newspaper. “It’s just a reflection of me. That’s the way I am. I’m interested in the theater and in books and sports and in religion and in the great questions of the day. The paper reflects that.” Powell recruited a heady staff, and nepotism was fine by him. Fredi Washington, his sister-in-law and an actress, was named entertainment editor. Ollie Harrington, a Yale graduate, was art editor. “It was quite obvious he was using the paper for his own purposes,” says Harrington, who lives in East Berlin now. “But nobody minded it. That’s what the paper was for.” Harrington was amused by Powell, who he says was always “flamboyantly happy.” Not everyone was amused. “Many considered him a con man, but a superior con man,” says Harrington. “He understood people quickly, then sized them up, then proceeded to overwhelm them.”

When World War II broke, Powell was in a unique position with his newspaper and city council post. He rallied against Hitler. He wanted blacks to get equal treatment in the military. “Is this a white man’s war?” he asked. He talked up Roosevelt’s policies and stewardship of the nation. When the People’s Voice could not meet its payroll one week, Powell dashed a telegram to Eleanor Roosevelt, urging her to send him money, quick, so that he might keep the paper afloat, keep praising her husband’s policies, for heaven’s sake, keep the country going. The First Lady said no. Everyone was writing and asking for money; a fledgling newspaper publisher was hardly at the top of the list to help. Powell managed to get the newspaper out anyway.

In mid 1942, at a Freedom Rally at Madison Square Garden, Powell announced he was running for Congress. Even though the election was a full year and a half away, there was much work to be done, and the early bird might get the milk and honey. It was a massive congressional campaign. Powell’s friends from the art community helped. Lionel Hampton contributed a thousand dollars. The poet Langston Hughes wrote a campaign song. Sara Speaks, Powell’s opponent for the new Congressional seat, painted him as a gadfly. But Speaks was clearly outmatched. She had no Abyssinian Baptist Church. Powell spoke everywhere. His father offered wise counsel, politics suddenly looked good; how high the moon? If elected to Congress, Powell promised, the first thing he would do was push for passage of “an Omnibus Bill for civil rights.” He said he would not be denied a Congressional seat, nor would he suffer again what had happened two years before, when, during a march on the Capitol, he had been stopped, “at gunpoint,” from entering the chambers of the House.

It was a huge victory, with Powell winning the vote of the American Labor Party, the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. He teased and said he didn’t know which party he would choose to sit with. Finally he decided to sit as a Democrat, becoming the first black from the Northeast to sit in the House of Representatives.

There was a little business to take care of before heading off to Washington.

Hazel Scott was a leading chanteuse at the time. She had a regular gig at Cafe Society, an avante garde club in the Village. Frank Sinatra and Lillian Hellman and Heywood Broun and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., hung out there. Powell met Scott at the club, began an affair, and wound up in Walter Winchell’s gossip column. Finally Isabel Powell had to do something. She went to court and sued. “I have since learned,” she said in the suit, “that my husband had lost interest in our marriage because of his infatuation with another woman. This woman is a nightclub performer. The short-lived turmoil in Harlem meant nothing to Powell. “I thought you were a man of the cloth,” someone asked him. “I am,” Powell said, “silk.”

©1988 Wil Haygood

Wil Haygood, on leave from The Boston Globe, is examining the life of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.