It was Congress that rescued Graham Barden, born in 1896, from a town called New Bern, North Carolina.

He would become a seaman, then a football coach, gleefully running up lopsided scores against opponents. By 1920 he had a law degree from the University of North Carolina. A winning football coach, in a small town, with a law degree, could surely achieve more than just Friday evening glory on a football field. So the football coach turned lawyer ran for county judge. He won. He tired of that job and ran for a seat in the state legislature, winning there, too. By 1935, the hometown walls had become too easy to scale. Graham Barden ran for Congress from North Carolina’s Ninth District. It seemed another routine victory. Barden would go to Washington as a Dixiecrat, a Democrat who was conservative and would align himself with conservative Republicans.

Like so many other southerners, Barden was destined to hang on in Congress, for years, until his seniority grew, until he himself had a chairmanship. A northerner might come to Congress for a few terms, to beef up the vitae, then break for Wall Street or a prestigious law firm. But a Southerner had no Wall Street or industrial oasis to return to. A southerner, a Strom Thurmond or a Graham Barden, might revel in the game of Congress itself, stay there, like Lee at Appomatox, to defend the South. In 1943, Barden’s perseverance paid off and he became chairman of the education and labor committee.

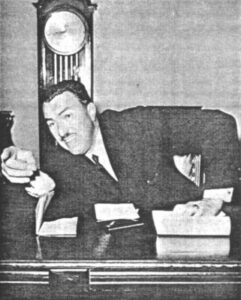

But Graham Barden did not like education and labor. He considered it his duty to keep the federal government out of the business of education and labor. To him education was getting up in the morning, going to school, coming home to study, then off to bed, a simple way of life that the federal government would best keep away from. Labor was nothing more than a day’s worth of sweat. So Graham Barden held few hearings for bills. When he did hold hearings, committee members would recall, he’d spend time reminiscing about his youth, and the football victories. His committee became known as the committee of “little education and no labor.” Barden himself had once remarked that he never knew the Republic to be endangered by “a bill that was not passed.”

By the mid-1950’s there were complaints from some of the young Congressmen on Barden’s committee. The complaints got loud, spilled over into the press, and turned into a revolt. Barden could not roll with the political winds, committee members said.

Barden had no apologies to offer. “I don’t have to look up the record to see how I voted on an issue five years ago,” he once said. “I know, because that is the way I would vote now.”

And yet the public mood was shifting for education and labor legislation. So Roy Wier and Mo Udall and Jim Roosevelt and Adam Clayton Powell went to Speaker Sam Rayburn and complained about Barden. Fed up with the discontent, Barden stormed out of one committee meeting: He would show them who was boss. When Graham Barden passed over Adam Clayton Powell for subcommittee chairman of education, a job he was entitled to because of seniority, he did it with swiftness and didn’t blink an eye. “Rank racism at its nastiest,” Powell cried.

Roman Pucinski had come to Congress in 1958 from Chicago. He was tough and liberal. His maiden speech was an attack on Barden for passing over Powell. Barden, taken aback, ordered Pucinski to sit down. “Mr. Chairman,” Pucinski said, “I got here the same way you did except that a lot more people voted for me than voted for you. I won’t be treated like a sharecropper.” Graham Barden had been in Congress since 1935, and now he had a revolt on his hands. Perhaps if he were younger he would have worked to silence the young turks. But the political winds were starting to shift, if ever so slightly. Education was being talked about. The Russians had sent Sputnik into space. Some were complaining that Americans were lagging in the fields of education and science. A nervousness spread across the land when a beep beep beep sound was heard coming from space. Some figured it was just echoes coming from Sputnik. Adam Clayton Powell, addressing a rally in Detroit, said he knew exactly what the beep beep beep sound was. It was a signal, he bellowed. that “the walls of Jim Crow are starting to come down!”

Clocks tick and perhaps Graham Barden was sincere when he said he simply wanted to go home to North Carolina and fish and be with his grandchildren. “It was the best kept secret in Washington,” recalls Jim Harrison, a labor and education committee member referring to Barden’s surprise announcement in late 1960 that he was retiring from Congress. Before stepping down, Barden helped defeat a minimum wage bill strongly supported by Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. The Raleigh News and Observer, which termed Barden’s quarter-century career “unproductive,” gave him a backhanded compliment when it said he had stayed “true to form to the very last.” It wasn’t the news of Barden’s retirement that sent shock waves through America, it was the revelation that his successor would be none other than Adam Clayton Powell. The pendulum was about to swing and the swing could not have been more wider. When news of Barden’s retirement reached Powell, he got down on his knees and “thanked God.” Then he went to his church in Harlem and told his flock that a new day was dawning. He made them feel the moment was a sweet event of divine intervention.

But now Graham Barden was gone and Adam Clayton Powell Jr., found himself in the spotlight. Now was the chance to prove his mettle. He would find a wonderful ally in President Kennedy. Kennedy, while campaigning for the presidency, had come into Harlem, was introduced to thousands by Powell, with Eleanor Roosevelt by their sides. Powell huddled with Kennedy at his Georgetown home to discuss the number one priority of the new president, which was domestic legislation. The administration knew how important Powell would be. There was a testimonial for Powell in Harlem, to celebrate his rise to chairmanship. Kennedy sent Arthur Goldberg and Abraham Ribicoff to Harlem. Ribicoff would praise Powell as a “great and eloquent advocate” for the downtrodden. He also said no issue would be more important than education legislation. Powell was downright effusive. “I personally come to this moment of a new era,” he said, “of a new administration, of a new Congress, totally free to do that which I feel is best for our land.”

“The Other America” was Michael Harrington’s portrait of a poorer America, less schooled, less well-fed, less well-off, a hurting America, hidden away in Appalachia and barrios and ghettoes. It was destined to become a reading classic. It was also the bible on which President Kennedy relied to fashion his attack on American poverty. He called his program the New Frontier. The majority of the proposed legislation would come through Powell’s education and labor committee. Powell looked forward to riding shotgun on the New Frontier.

Now, with a new president, a young president, it was a good time to be in Washington. Spunk was back in vogue and there was an air of New Deal-ism. Idealists rushed into Washington, their briefcases bulging with ideas. Old heroes from the Roosevelt years, like Wilbur Cohen and Robert Weaver, were still around. This might be their last hurrah. Powell himself had come to Congress with the FDR landslide in 1944. This would not be his last hurrah, but it was going to be an interesting ride anyway. Applications flooded into Powell’s office. He had doubled the hiring budget. Washington, in 1961, before the 1964 Civil Rights Act and anti-discrimination laws, could be a cold place for a black intellectual. You could, however, avoid that climate if you were lucky enough to get your application in the hands of Powell. He served notice his staff would be integrated, and it was, a model of affirmative action before the term would be coined. Suddenly his committee seemed the committee to work for; suddenly education and labor seemed spicy.

“The place is crawling with Ph.D’s,” Powell bragged. Deborah Wolfe was the type of worker Powell sought. Wolfe was born in Cranford, New Jersey. Her father was a preacher, and he believed passionately in education, as so many black clergymen did. He sent his daughter to Tuskegee Institute. She graduated at the age of 20, then stayed on, developing the school’s rural education program. She got her doctorate from Columbia University, and someone bought her to the attention of Abraham Ribicoff, Kennedy’s secretary of health, education and welfare. Wolfe said she knew nothing about health or welfare; education was another matter. She wanted to educate.

Powell offered her the job as his chief of education legislation. This was a break with tradition, inasmuch as most committees were run by lawyers. Wolfe thought Powell’s approach to education novel. “He believed that education was the major strategy for upward mobility,” she recalls. So she did research on education, read everything that she might not have read during the previous ten years on education. She would get businesses to invest in educational tools then have staff members in the office try them out. She would grab Congressmen from the hallways, shoving them into her office, to read this document, try that gadget, look at those statistics. People would say to her, “Deborah, don’t you miss teaching?” And she would say, “But I’m teaching the Congress!” The southern Democrats would stifle President Kennedy’s education bills. But little by little the evidence was being accumulated. It would not be long now; if not this session, then surely the next session.

Powell not only gathered a heady staff, he loosed the Congressmen on his staff who had been waiting for this kind of opportunity. John Brademas was a brainy young Congressman from Indiana. He had been a Rhodes Scholar. His specialty would be education. Jim O’Hara came to Congress from Michigan. He would study the Rules Committee, becoming an expert at how to maneuver a bill. Frank Thompson was a slick Congressman from New Jersey, a man of culture and an admirer of the arts. Edith Green, who had run Kennedy’s campaign in Oregon, her home state, would draw attention to the problems of juveniles in society. Powell turned them all loose, sent them on fact-finding missions, chaired the hearings. “He had these eager beavers on the committee,” recalls Congressman O’Hara, “who wanted to change the world. He pushed them.” Powell knew politics was a game of compromise. He made an effort to appease the Republicans–now minority members–of the committee. “I’ve given the Republicans more patronage than they ever got–$50,000 in salaries,” he noted. “No other committee has ever given them half that.”

Subcommittees were formed on education, the arts, juvenile delinquency, and vocational education. Diseases would be cured, scientists would be given grants, children would be better educated. The other America would be recognized.

It got dizzy. No other chairman held as many hearings as Powell. Experts stormed into Washington to testify before his committee. They came with passion in their eyes. They came to change public opinion, to say that yes, the federal government could make a difference, must make a difference. New Deal then: New Frontier now. Blacks felt particularly emboldened by Powell’s new stature. He reached out to the historically black colleges and had experts from those schools come to Washington to testify. He never forgot his home district, and sometimes would swoop into New York City, with an entourage, and conduct hearings right at the federal courthouse at Foley Square. ‘Dust will not gather on these hearings,” he promised. The hearings themselves were something approaching New Theater.

Waitresses from New York City came to Washington to testify before Powell’s committee about low wages and unfair treatments in the labor market. One waitress said she had been threatened not to appear before the committee. “Call my office,” Powell said to her as she sat on the witness stand. He’d provide protection. He was like a prosecutor stacking up the evidence. “The hearings,” recalls Congressman Jim Roosevelt, a member of Powell’s committee, “aroused support for legislation.” Powell said his hearings on the garment industry would be aimed at “the substandard living conditions of the garment workers and its relation to racial discrimination, racketeering, and the callous disregard of officials and others who have assumed a position of trust.” Union bosses said they would not show up for any damn hearings. Powell threatened them with subpoenas and they came.

There were hearings in 1962 on the entertainment industry. Diahann Carroll, the actress, appeared before Powell’s hearings and told of her woes. “I’m living proof of the horror of discrimination,” she told Powell. “In eight years I’ve had just two Broadway plays and two dramatic television shows. Seven and a half years without a Broadway show. I’ve asked myself why.” The great actor Sidney Poitier appeared before Powell and told of his unhappy feelings about being the only black star during the 1950s and early 1960s. Powell vowed further action: “I will put in the budget enough funds for the committee to go to California and look into the movie industry.”

Juvenile delinquents had been rounded up to appear before the committee. They told of living on the streets, of selling drugs, of not being able to find jobs or counseling. So the evidence piled up and the bills would start to be passed. A minimum wage bill, historic, was passed. A juvenile delinquency act was passed. Much of Kennedy’s domestic legislation would be trapped by the southern Republicans and Democrats. But the imprint was there: the other America’s time was coming. Then the young and handsome president went off to Dallas, Texas for a visit.

The bills that languished under President Kennedy had a new, even more vigorous leader in President Johnson. Johnson would bully Dixiecrats to vote with him. “Can-do” was his motto. “Get ready to go, Adam,” he said to Powell. Everything now was jets taking off. Bills were sent to Powell’s committee, shaped and sent over to the Senate and then back to the president for a hard stamp. There wasn’t even time for ink to dry on these bills. They just kept coming and Republicans started to complain they were being run rough-shod over, which was the point of it all. Powell and Johnson were uniquely suited for this task and each other. Both could be charming politicians one minute and vulgar operatives the next. Both commanded attention and had the bravado of Willy Loman on a doorstep at sunset.

Now in the dizzy afterward of a 1964 landslide, Powell and Johnson spent money and introduced bills. The education bill was passed, along with many others–involving manpower, Head Start, Medicare, lunch programs, college loans, all under the war on poverty umbrella. The president told Powell he was just flat-out “brilliant,” and Powell seemed to laugh, as if he had known it all along. However, Powell was not always cozy with the administration. He held up bills in his committee when he thought they needed more money.

“He never talked about the number of bills, but the millions of dollars being spent,” recalls Michael Schwartz, a top Powell aide.

Powell accused the administration of not looking hard enough for black judicial candidates. “Seek and ye shall find,” he advised. He would fly into Harlem and bask in his power, donning his preacher’s robe, walking hand in hand with striking hospital workers, reminding them, lest they forget, as he sometimes would, that power wasn’t everything, that he was still common, that he himself was “an ole picket walker.”

The lines between folk hero and tragedian are often blurry. When demons from the past come back to haunt, or recent events curtail the power, the blur lessens. Torn between his political genius and the tragedian that lurked in his very own soul, Adam Powell would take too long to realize the fragility of political power. He had an uncanny knack for pulling himself up from cliffs: tax trials and church scandals and nasty divorces.

He had double-crossed politicians in the past, as they had double-crossed him. But politicians have long memories. So in 1966, when allegations began to circulate about a misuse of committee funds on Powell’s staff, the job of investigating fell to Wayne Hays, of the House Administration committee. In 1956 when Powell had bolted his party and supported Eisenhower for the presidency, Hays was livid, suggesting that Powell be stripped of his seniority.

Powell, in another one of his huge, ribald, well-meaning investigations, had accused a New York lady of accepting payoffs from the New York police to cover up rackets involvement in the police department. The lady sued for libel and won and Powell refused to pay.

Hays had enough evidence to go a step further. He turned his findings over to Emmanuel Cellar. Cellar, head of the House Judiciary Committee, was an old liberal from Brooklyn, a force in getting the 1957 Civil Rights Bill passed. Powell refused to help Cellar with the civil rights bill in 1957 and Cellar expressed outrage. Cellar formed a select committee to investigate Hays’ findings.

The threat to Powell’s political survival was now real. There were rumors, laughed at, at first, that he would be censured and fined and even kicked out of Congress. It was a habit of Powell’s that he could harness passion of a legendary kind; he was more than just one person, more than just Harlem’s Congressman. He was the Congressman of black America, of the downtrodden, of Mississippi sharecroppers, of old Latino women in the Bronx, of Mexican fieldworkers in California. A threat against his survival seemed a threat against their survival.

The old civil rights heroes, Roy Wilkins and A. Philip Randolph and Gardner Taylor, came to Powell’s defense. A group of workers in Detroit said a work stoppage would take place if Powell’s seniority was tampered with.

“Their combined voices raised in my behalf has made it clear to me that the fight to retain my chairmanship–and this is really the only issue in this struggle–must be militantly pressed,” Powell said in early January of 1967. Days later he would be expelled from Congress in a surprise move that pitted liberal against liberal and conservative against conservative, that turned him into another battle-scarred 1960s figure, as romantic and tragic as the decade itself. His fate would go all the way to the Supreme Court, where the Warren court would have things to say about piety, as well as the powers of Congress.

© 1989 Wil Haygood

Wil Haygood, on leave from the Boston Globe, is examining the life of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.