Marie St. Fleur makes her way to the podium, zigzagging between the banquet tables, tossing a wave here, touching a few outstretched hands there, smiling like she’s buoyed by the warm applause and the giddy expectation coursing through the Miami hotel ballroom.

SIDEBAR - Up and Coming: Other Haitian-American Women Making Their Mark

Up and Coming:

Other Haitian-American Women

Making Their Mark

Marleine Bastien – Executive Director of Fanm Ayisyen Nan Miyami Inc. (Haitian Women of Miami Inc.)

Ms. Bastien co-founded the organization, known as FANM, in 1991 with 12 other Haitian-American women. A clinical social worker, she said she got the idea after seeing many Haitian women in crisis who didn’t know were to go to for help for social, economic and cultural problems.

The Miami Herald, in a special millennium edition, named Ms. Bastien and another Haitian-American women, among the “40 special people who will make South Florida’s next century as exciting and unpredictable as the last one.”

Last year, Amnesty International gave her a human rights award for her work on behalf immigrant women and children. She was also selected Volunteer of the Year by the Miami-Dade County Commission in 1995.

She says a decade ago the organization had no voice in South Florida. Now she and other FANM representatives are often asked to speak at universities and churches, and to address women and business groups. Two of the organization’s platform positions where selected for roundtable discussions at the United Nations World Conference on Women in Beijing China in 1995.

“For the last three years people have been trying to enlist me to run for office,” she said. “However, I haven’t made the switch from community activism to political activism. It would be a natural transition but mentally I’m not ready. I feel there’s too much to be done. What about FANM’s vision? What about the women I would leave behind? So many are not empowered. I don’t see myself leaving all of that.”

Therese Guilloteau

Consul General at the Haitian Embassy in New York

Before she became the first woman consul general at the Haitian Embassy in 1998, Ms. Guilloteau spent the previous two decades working on women’s issues and trying to raise the political profile of Haitian women throughout the United States.

In 1983, she arranged a conference in New York City that brought together Haitian women’s groups to organize around issues affecting Haitian women living outside of Haiti and to develop a common policy platform. Out of that conference, The Committee of Haitian Women in New York was born. Two years later, she traveled with a delegation of Haitian women to a United Nations conference on women in Nairobi, Africa to present a policy paper on Haitian women in the Diaspora. In 1993, Ms. Guilloteau organized another conference to develop a strategy to help Haitian woman move into leadership positions in their communities. About 170 women showed up.

Ms. Guilloteau returned to Haiti in 1995 to become Minister of Women’s Affairs, a cabinet level position. While there, she created the League of Women in Power, which provided leadership and assertiveness training seminars for women political candidates.

“In the 1970’s,” she said, “you found women activists working in the churches and in the community centers. They use to work behind the scenes. They didn’t want to show themselves too much. They didn’t want to hold positions but they were always willing to help. I think now they understand their value and they are not shy about saying so and are coming out and writing and talking about it. They are taking leadership positions and staking their claim.”

Leonie Hermantin

Director of Research and Development,

Haitian Neighborhood Center

A relative newcomer to South Florida’s entrenched Haitian-American political scene, Ms. Hermantin has nonetheless made a name for herself. She came to Miami in 1994 and by 1998 she was executive director of the Haitian American Foundation, Inc. a leading social service and economic development agency she lead until last summer. Politicians of various political stripe and ethnicity seeking the Haitian community’s support often go to her.

Ms. Hermantin recently joined the newly created Haitian Neighborhood Center, which aims to become a primary research center on Haitian-Americans. A Democrat, she was appointed to the Florida Commission on Human Relations last year by Republican Gov. Jeb Bush. She is also on the advisory board of the Alliance for Human Services, an organization responsible for identifying the funding priorities for health and socials services for the Miami area.

She was one of only two Haitian-Americans cited by The Miami Herald as one the “40 special people who will make South Florida’s next century as exciting and unpredictable as the last one.”

Ms. Hermantin left Haiti at age 12 and moved with her parents to Manhattan’s upper west side, once home to a small but vibrant Haitian community. By the time she was a teenager she was a political activist , taking part in protests on behalf of Mexican farm workers. She carried that social consciousness with her to New York University, but dropped out to be a full-time activist. (Among her activities were protesting the 30-year Haitian dictatorship of Francois and Jean—Claude Duvalier.) She eventually got her bachelor’s degree in Latin American studies at the University of California at Berkley.

“People think of me as a leader but I don’t consider myself a leader in the sense of traditional political leadership,” she said. “I consider myself a part of the social service community who has to negotiate politically to get things done for the community, to articulate the needs of the community and try to define policies that affect the community.”

Jocelyne Mayas

Project Associate at the New York State Citizenship Unit

Ms. Mayas was appointed to the newly created agency by Gov. George Pataki last spring to help new immigrants to the city. The job is very much like what she had been doing on a voluntary basis for the last 10 years, but now she is being paid to do it. She handles immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa and French-speaking countries, helping them find social services and employment, negotiate the public school system and solve problems with work benefits and tax issues.

Ms. Mayas worked for the Bankers Trust Company for two decades working her way up from a clerk’s position to become an assistant bank vice president. She left the job in 1991 to become a full-time street activist, joining other Haitian immigrants in vocally protesting the military coup that year in Haiti that toppled the country’s first democratically elected government in almost 200 years. They held rallies outside the United Nations and U.S. government offices, organized news conferences to bring attention to their cause, and lobbied Congress to oppose Haiti’s military regime.

She and four other Haitian-American women eventually formed Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees to act as a liaison between Haitian refugees who fled Haiti and the agencies in New York that were helping resettle them.

In 1996, she started offering weekend literacy and civics classes to help Haitian immigrants pass U.S. citizenship tests and be eligible for certain benefits that newly enacted immigration laws denied to non-citizens. The classes are held every Saturday morning at a Brooklyn church. After classes, Ms. Mayas and other volunteers interpret letters and government correspondence for the immigrants, offer job counseling and referrals, and help link them to other social service agencies.

She has been honored by New York’s city hall, the governor’s office and by several local Haitian organizations. She also received an award for her volunteer work from the International Immigrant Foundation in Manhattan.

“No, I don’t want to run for office,” she said. “Yes, I want to remain in politics purposely to educate my community to help them make the right moves and the right choices. I don’t need to be in the limelight, I just need to make sure there are more people like myself and in order to do so I have to keep doing the grassroots work that I do.”

Gepsie Metellus

Executive Director, Haitian Neighborhood Center

Ms. Metellus is well known in Florida for her advocacy work on behalf of Haitian-American women and Haitian political refugees. The former director of public affairs for the Miami Board of County Commissioners, she has been asked repeatedly over the years by both Haitian and African-American political leaders to run for local or statewide office. She says she’s not ruling out a future political career.

Last September, she launched the Haitian Neighborhood Center, a resource and advocacy center. A former high school French teacher, she is a poised and very effective public speaker and can often be found at public forums or on television programs defending Haitian rights, explaining Haitian culture, or pushing a pet political cause. She is a founding member of Haitian Women of Miami, the Association of Haitian Educators of Dade County and The Haitian American Grassroots Coalition.

An 18-year-resident of South Florida, she cut her teeth in immigrant politics in 1983 as a recent college graduate and transplant from New York City when she joined several Haitian cultural organizations. She eventually joined the board of the Haitian Refugee Center, once one of the more influential Haitian advocacy organizations in the United States, and became the board chairwoman.

“A new era has been ushered in by Haitian women who finally accept the fact that they have a great deal to offer to their communities,” she said. “Some people are uncomfortable with that and many of those people are men. Women have always had the skills and talent and that special way of making sure things got done. It’s not by accident that we have always been the backbone of our community. This is our time to break free from the mold that kept us confined and did not allow us to explore our full potential.”

©2003 Marjorie Valbrun

Marjorie Valbrun, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, is researching Haitian immigrants’ emerging American identity.

“This is going to be good,” one woman says to another seated beside her, as Ms. St. Fleur passes their table.

When she reaches the podium, Ms. St. Fleur scans the room and nods her head in approval.

“Fanm Haitian nan Miami” she proclaims loudly in Creole. “Mwen voye yon kout chapo.”

“Haitian Women of Miami,” she says. “I tip my hat to you.”

She praises her hosts for helping to empower Haitian women but warns, “Ladies, we still have a long way to go.”

“I think we must shape our own destinies here in this country,” she says. “Power concedes to no one, you must go out and get it.”

Before long, the event sponsored by the organization, Fanm Haitian nan Miami, is transformed from just another banquet room fundraiser packed with civic, business and political leaders, into an Oprah Winfrey moment.

The women in the audience clearly connect with Ms. St. Fleur, a Massachusetts legislator and the first Haitian immigrant elected to a state office in the United States. They nod their heads in agreement as she speaks, soaking in her every word like some feminist elixir. They beam like proud siblings watching a sister perform on stage, and swathe her in a collective emotional embrace.

It’s as if they traveled the long road with her, from Haiti, to Boston, to high political office in the House of Representatives. To them, Rep. St. Fleur represents a burgeoning spirit of feminism and political empowerment among Haitian-American women in the United States. Hers is the image of the new Haitian woman: educated, ambitious, politically conscious, and most of all, in charge.

And lately, this new image has earned a place in the political movement occurring in Haitian-American communities throughout the United States. Haitian women now stand along side of, instead of behind, the men who have long dominated Haitian-American political activism, monopolized leadership positions and shaped the group’s political agenda in this country.

Nowadays, the women say, they are speaking for themselves. That’s no small feat for women who came of age in a deeply patriarchal culture and were born in a country where men traditionally controlled most aspects of society and government.

“In Haiti, your primary role is to take care of the family, the kids, the husband. But here it’s not necessarily so,” says Lola Poisson, who came to the United States 33 years ago and is running for a seat on the New York City Council. “Here the women are starting to look at politics and saying ‘Hey, the men didn’t do it all.’ We can bring something else to government and politics.”

Ms. Poisson, a social worker, started and ran a Haitian community mental health center called Lakou Lakay, or Our Backyard. She is a Democrat but is running on the Independence Party ticket and hopes to represent her district in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn.

“I have been involved for 20 years, doing community work,” she says. “I started the community center from scratch. I decided to run for office because I felt I had a chance to take my work to a different level and have an impact on the community.”

Along with women like Ms. Poisson, who grew up in Haiti and are approaching middle age, are younger Haitian-American women who were raised and educated in the United States and saw firsthand the benefits of political engagement.

“As a new generation, were not thinking how our mothers and grandmothers were thinking,” says Farah Tanis, 29, executive director of Dwa Fanm, or Women’s Rights, an advocacy organization based in Brooklyn, NY. “We have developed a sense of ownership of our citizenship, our rights, and our ability to make decisions and affect policies and government.”

Among other things, Dwa Fanm provides leadership development training for women, runs an empowerment program for girls and conducts a domestic workers’ rights seminar.

Other organizations have taken note of Dwa Famn’s work and “are becoming more aware and prioritizing women’s issues,” says Ms. Tanis. “Our name says it all. They want to talk to us, hear about our programs, and see how they can coordinate with us.”

The increased visibility of Haitian woman activists and politicians can only enhance this momentum, she says.

“Now young Haitian women can see there are models out there, Haitian women who are making it and who are having an impact. And as different generations come up, it will get stronger and stronger.”

Still, Ms. Tanis notes, the political activism by Haitian women is inextricably linked to that of Haitian men because ultimately each side’s political successes benefit the Haitian community as a whole.

“White women, African-American women and women from other immigrant groups have been running for office and have been politically active and vocal for years,” Tanis says, “but throughout the 1980’s, Haitians struggled through obstacles we had to overcome as a group.”

Those obstacles included the Haitian refugee crisis of the 1980’s, tough immigration laws that targeted and penalized refugees feeling poverty and political persecution in Haiti, and a U.S. government classification of Haitians as a high risk group for the AIDS virus. Widespread protests by Haitian-Americans, led to fairer immigration laws, amnesty programs that legalized thousands of illegal Haitian “boat people” and removal of Haitians from the government list of AIDS carriers.

“Out of that, we have developed a new sense of group pride, a sense that we belong here and deserve to be here like everyone else,” Tanis says

Group pride notwithstanding, there is palatable sense of excitement in some quarters specifically about the emergence of Haitian women in politics.

Ms. St. Fleur, the Massachusetts lawmaker, is a rising star in the national Democratic Party. During the presidential campaign last year, she traveled the country stumping for Al Gore in cities with large Haitian populations. People in the Little Haiti section of Miami still talk admiringly about how her oratory skills rivaled even Jesse Jackson’s. (The civil rights leader shared a stage with her during the campaign.) Although she is only in the first year of her second term, the state Democratic Party chairman has already approached her about running for secretary of state. She was also recently appointed to a House leadership position as vice chair of the Committee on Counties.

Ms. St Fleur, 39, who immigrated to the United States with her parents when she was six years old, was first elected in a 1999 special election to complete the term of a state representative who left office to go work for the Boston mayor. The city’s political establishment lined up behind her, including Mayor Thomas Menino and Scott Harshbarger, her former boss and the attorney general at the time.

She had so much political and financial support from influential power brokers that her two opponents called her the “downtown candidate.” But Ms. Fleur had already earned political capital working as an assistant district attorney and an assistant attorney general for several years.

Unlike her counterparts in South Florida where ethnic politics rule, Ms. St. Fleur ran on a platform that focused on education, public safety, economic development and affordable housing. However, local newspapers and television news programs made much of her immigrant background and it seemed to play well with voters. She won with 77 percent of the vote. When she ran for reelection in 2000, she got 73 of the vote.

A mother of three, she gets invited to speak to Haitian women’s group around the country and not only because she has redefined old-fashioned notions of what a Haitian woman, wife and mother should be. She is also respected because she has jumped over race and gender obstacles and is now playing politics with the big boys.

“Haitian women have more education than ever before,” Ms. St.Fleur, who has a law degree from Boston College, says explaining the current trend among her female compatriots. “They’re less fearful about change. They feel they have more control of their destiny and don’t have to rely on men for their livelihood. They came to this country and saw the women’s movement and it influenced and changed them.”

In Boston, Ms. St. Fleur’s hometown, the requests for her time are even more numerous, and they come not just from women’s groups but from Haitian civic and political organizations, community service centers, churches and just about any Haitian with a problem. Yet Haitian residents make up less than two percent of her district. Unlike in Florida where eight Haitian-Americans hold elected office, she is the only Haitian-American in public office in her state.

“I think it’s a whole level of pressure that I had not anticipated,” she says. “It created positive energy in the community but also put pressure on me. Sometimes I have to tell them that my main priority is the people in my district not the whole Haitian community. I tell them, ‘Use me as an opportunity to empower yourself, demand of your state representative what you see me doing.’”

Still, she admits she has a hard time turning people down when they ask for help. She knows what her position and those of other Haitian-American lawmakers mean to Haitian immigrants who are use to feeling powerless and know little about negotiating the American political system.

“Symbolically, we’re creating momentum for the Haitian community to have a political identity and that’s very important,” she says, adding that Haitians in Boston make up a third of the city’s black population. The city is home to 80,000 Haitians, the third largest Haitian population in the United States behind New York and Miami.

“To me that suggests we need to understand that point of influence and know how to use it,” she says.

Some Haitian-American women say that’s precisely why female activists should be careful not to distance themselves too much from their male counterparts. There is strength in numbers they say and more political power with experience.

“We have a group of Haitian women here who are emerging as leaders and most of us are relying on men to help us get there because they are at the forefront, they are in power and they have more clout and more money,” said Margareth Jourdan, the first Haitian-American municipal judge in Spring Valley, NY, a suburban, upstate community with a sizeable Haitian population.

Ms. Jourdan, 40, a mother of four and former village trustee and immigrant rights attorney, was appointed by the village mayor last June to complete the term of a retiring judge. She is now running for reelection for a full, four-year term.

“I was very lucky that the mayor recognized my ability and asked me to run with him as a trustee,” she says. “Had it not been for him, I probably would not have gone into politics. Women at this point, we are new at this game, we don’t have the numbers, we don’t know all the key players and we must rely on the men who have gone before us.”

Ms. Poisson, the Brooklyn City Council candidate says she has found the sisterhood of activists lacking.

“I have more support from the men than the woman,” she says. “They respect me, they like me, they appreciate the strength that I have. The few men who were against my running, I can count on my fingers.”

Ms. St. Fleur and others do credit their male counterparts for the paths they’ve blazed. — Ms. St. Fleur speaks highly of Phillip Brutus, the first Haitian-American in the Florida House of Representatives, and he is a great admirer of her as well. — They just think it’s time the woman took center stage.

Not surprisingly, the emergence of the women activist has caused some rifts in the Haitian community and in once traditional Haitian households.

A few of the women activists spoke confidentially about now troubled marriages and unsupportive husbands who threatened to leave them when their stars started to rise. Some said their husbands had become emotionally abusive or distant.

“To be in a women’s right organization, you have to have support at home,” said Ms. Tanis of Dwa Fanm. “There’s pressure, there is insecurity, and it does create issues. I have been called a male-basher, even by Haitian women.”

A telling moment came last Spring when Ms. St. Fleur addressed the women’s group in Miami and spoke about domestic violence, an issue at the top of many of the women’s organizations’ agenda but a taboo subject in some Haitian circles, especially in public forums.

Ms. St Fleur was unapologetically blunt that night. “Haitian women must have zero tolerance for domestic violence,” she said forcefully.

Some of the men in the ballroom looked visibly uncomfortable. A few glanced at each other.

A man seated at a table full of woman scowled, then mumbled audibly, “What it this? Bash Haitian men night?”

Eno Mondesir, chairman of Haitian-Americans United Inc., a Boston community organization, said the problems are based in part on Haitian cultural beliefs that politics is aggressive and male dominated “and so women don’t belong there.”

“Plus you have a strong religious faction in the community that feel that politics is dirty and must remain in the hands of the crooked,” he says.

Ms. Mondesir who teaches a course in human growth and development at Roxbury Community College in Boston, says these notions are changing “but slowly.”

“Because we are an expatriated community, there are many other issues and obstacles to confront,” he says, “so discussing women in politics is not an issue that comes to table everyday. Until the men say, ‘If I share the power, I may become stronger in many ways because there will be more people in the power base,” until ignorance fades out and gives way to this kind of thinking, there will be pockets of resistance.”

In the meantime, the Haitian-American women aren’t waiting for the men to come around.

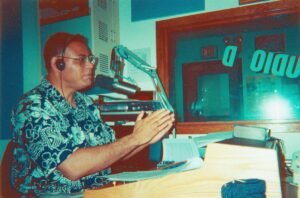

“We’ve been wanting to come out for a long time,” said Florence Bonhomme-Comeau, a business woman and former host of a long running Haitian radio program called Pawo‘l Famn, or the Word of the Woman. “This is not something that we were given, this is something that we have earned.”

©2003 Marjorie Valbrun

Marjorie Valbrun, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, is researching Haitian immigrants’ emerging American identity.