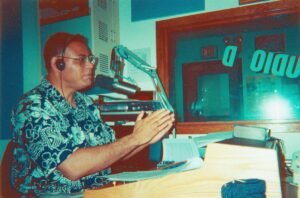

CHICAGO – A lazy, humid afternoon in the Windy City. Unity Radio is on the air. The topic? Politics. The opinions? Endless.

Today’s subject is the controversial presidential elections of last fall. The amateur commentators trade political views like sports announcers rattling off the minutia of a post-season game.

If you thought that by now even talk radio would have tired of mulling over the election results, you might have been right if this weren’t a weekly radio program run by and for local Haitian immigrants.

On this day, the disputed vote tally they are discussing is not the one that put George W. Bush in the White House. It’s the one that happened “back home” – in Haiti.

During the two-hour Creole language talk show, the subject of U.S. politics never comes up. Not the recent city council races or upcoming campaigns for the state legislature. This political discussion may be in America, but it’s certainly not of it.

Haitians here are deeply tied to Haiti and are acutely interested in what’s happening there, explains Willy Pompilus, a guest on the show.

“When you come to this country, you make a big decision,” he says. “And one of the first things you ask yourself when you arrive is, ‘What can I do for myself? And what can I do for Haiti?’”

This sentiment is illustrative of the gulf separating Midwestern Haitian communities like Chicago’s from their larger, better-organized, more influential counterparts on the East Coast.

While Haitian immigrants in Florida are fast becoming part of the mainstream political machine, those in the Midwest continue to lag behind, failing to even articulate a set of political priorities.

As Haitian immigrants throughout the country become U.S. citizens by the thousands, register to vote in record numbers and run for public office “U.S. style” in cities with large Haitian populations, Haitian activists in Chicago wrestle with a subtle conflict. They are torn between focusing on politics in Haiti and politics in the United States, trapped between allegiances to their countrymen back home and political realities facing their compatriots here.

Some Haitian-Americans say the political leadership has spent far too much time talking about Haiti and not enough time developing a focused political agenda for Haitians in the Chicago area. Others charge that Haitian activists here were slow to embrace the idea that by immersing themselves in U.S. politics, they might also affect politics in Haiti.

In the meantime, Massachusetts, home to a large Haitian-American community in Boston, and Florida, home to the nation’s second largest Haitian population, both have Haitian-American office holders in their state legislatures. There are now eight Haitian-Americans in elected office in South Florida, including the mayor of North Miami. Haitian immigrants there now talk about sending a Haitian-American to Congress. In New York City and New Jersey, several Haitians have announced candidacies for state and local offices.

There is just one elected Haitian-American official in the Chicago area, an alderman in Evanston, a suburb that straddles the city’s north side where many Haitian immigrants have settled. Lionel Jean-Baptiste, an attorney in private practice, was elected on April 3, becoming the first Haitian-American in the state to hold public office. Of the 8,000 residents in his ward, only about a hundred are Haitian and only about 30 of them registered voters, but that hasn’t stopped Haitians throughout the region from claiming him as their own. Eighty percent of the financing for his campaign came from Haitian donors.

Still, the community has had difficulty asserting itself.

“Without a critical mass, the extent of your being able to make yourself visible as a community and having an impact on the larger community will be limited,” says Jean-Baptiste. “And so will the likelihood of the larger community taking you into account, being sensitive to your concerns and accepting your demands.”

Indeed, Illinois’ Haitian population of about 15,000 is much smaller than that of Haitian communities on the East Coast. There are about half a million Haitians in the New York, New Jersey and Connecticut region, about 250,000 in Florida and about 70,000 in Massachusetts. Unlike those states, Illinois’ Haitian community is widely dispersed, with small enclaves of Haitian professionals, middle and working class people and poor, undocumented refugees scattered in small clusters in and around Chicago. There is not a Little Haiti neighborhood here, like in Miami, to act as a voting block. There are not any boat people washing ashore to grab headlines and energize grass-roots movements. There is no Abner Louima, (a Haitian immigrant whose sexual assault by New York police was widely publicized) to prompt outrage and bring the community together, or an Elian Gonzales to illustrate the disparity in immigration laws toward Haitian refugees.

When hundreds of angry Haitian voters took part in street protests in Palm Beach County last fall, claiming that they were turned away from the polls during the U.S. presidential elections, all Haitians here could do was watch them on television with a degree of admiration.

“The problem is we cannot find our driving force,” says Owen Leroy, explaining that while local Haitians may have some of the same unique concerns and problems as Haitians elsewhere, they don’t have the same political issues to coalesce around and build on.

Mr. Leroy has lived in Chicago for 20 years and started the city’s first Haitian radio program, Bonjour Soliel (Good Morning Sun), which aired for 14 years. He is pessimistic about the prospects for local Haitian political empowerment. He says because the community is spread out, there is a tendency among activists to think narrowly — focusing on particular Haitian neighborhoods, for instance, rather than on all Haitians in the region – and to compete instead of pooling limited resources. (Last year, three members of the main Haitian-American civic organization, citing philosophical differences, broke away and formed a separate organization. The Haitian American Immigrants Association is now located just a few blocks away from the more established Haitian American Community Association and offers similar services.)

William Leslie Balan-Gaubert, a Haitian historian and scholar in residence at the University of Chicago, says the lack of connection is due to ambiguity among local Haitians about the word “community.”

“They think it means having a place to gather,” he says. “They don’t see it as a sense of belonging, a sense of cause, a sense of caring about issues that are relevant to Haitians.”

Clausel Rosembert, consul at the Haitian Consulate here for the last seven years, says things are starting to change. When he first arrived he perceived a fixation on Haitian politics among the local Haitian community. “They would be concerned about issues and offer opinions and criticisms about complex situations in Haiti that they didn’t truly understand and meanwhile they were ignoring local and national issues that really affected them,” he said.

Questions about whether to become a U.S. citizen caused great anxiety for some people.

“They used to come up to me to explain, almost apologetically, why they were becoming U.S. citizens,” he says. “They considered it a betrayal, they felt disloyal to Haiti and would be embarrassed to tell their friends.”

A few years ago, Rosembert started to notice changes in attitudes. Established organizations that once focused on helping Haitians in Haiti started talking about helping Haitians here. The Cook County Voter Participation Organization was created to register naturalized Haitian-Americans to vote. He attended its first fundraiser at which a local alderman was invited to speak.

Jean Andre Gerard Bingue, executive director of the Progressive Haitian American Organization, who started the Haitian voter group, has been involved in the campaigns of several local aldermen, including Jean-Baptiste’s, and two congressional candidates’.

“I did it because I saw the necessity,” he says. “We have to involve ourselves in the American political process.”

Jean-Baptiste realized this long ago too. Over the years, he kept busy doing grass roots organizing, serving on his city’s civil service commission and on a U.S. congressional advisory committee on Caribbean affairs, in effect laying the ground work for his entry into politics.

His nationality was not an issue in his campaign but it played a role in his decision to seek office.

“I asked myself, ‘Wasn’t it time for us to step into the mainstream of American life and come out of the invisibility,’” he says. “The answer was, ‘Yes.’ It’s no longer a safe haven to be on the outside. We have to engage in civic duties that transcend our own nationalistic or ethnic boundaries.”

Lionel Chery, chairman of the Haitian-American Community Association, which provides housing and translation services, immigration and food assistance and legal service referrals, says natural leaders like Jean-Baptiste are key to moving the community from the political sidelines.

In 1991, after a bloody military coup in Haiti, Chery and other Haitian activists led weekly marches to the federal government building in downtown Chicago to draw attention to U.S. foreign policy in Haiti. They also called on the first Bush administration to prod the Haitian military to relinquish power to the democratically elected government.

Even in their community building efforts however, Chery and others had to be mindful of Haitians’ tendency to distrust those involved in politics. Political differences caused huge fissures in Miami’s Haitian community — and even violence – between those who advocated U.S. involvement in Haiti to restore a democratic government to power and those who supported the 1991 military coup.

Chery’s 20-year-old organization was dormant from 1994 to 1997 because of political infighting. When it was reactivated, “We made a choice not to get involved in Haitian politics,” he says. “We didn’t want to alienate segments of the Haitian community.”

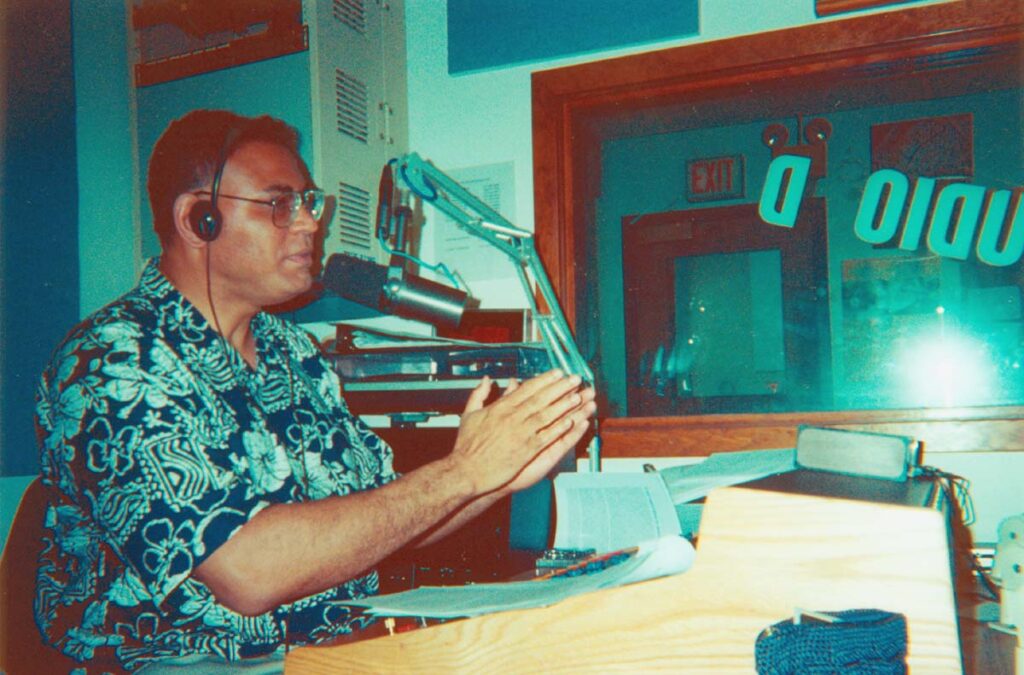

Harry Fouche, a 30-year Chicago resident and host of the Unity Radio program, says Haitian communities throughout the country are all reaching political maturity after a lengthy and difficult period of adjustment. Some communities reach it sooner, he says, but they all make the same journey.

“I think each Haitian community has its own peculiarity,” he says. “Being a smaller community, there are many things you would not have expected to happen here that have and many things you would have expected to take place in Miami but didn’t. Even in New York there was never really any integration into the mainstream political structure until recently.”

Fouche, a research economist for the state employment security department, looks to the children of Haitian immigrants who already see themselves as Americans to make that integration happen.

“You have a generation of Haitian-Americans coming up that believes that they must invest in their future,” he says. “They will make a real difference in how the community is perceived, either as a player or as a passive spectator.”

©2002 Marjorie Valbrun

Marjorie Valbrun, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, is researching Haitian immigrants’ emerging American identity.