Phillip Brutus insists he isn’t nervous, but there is an anxious edge to him on this first day of the Florida legislative session. It’s there, in his clipped conversations and his hurried gait as he walks the halls of the State House, shaking hands with this Senator and that Representative, popping into the offices of certain influential lawmakers, checking his Palm Pilot repeatedly to keep on schedule.

In addition to the countless ceremonial receptions marking the start of the session, there is a Democratic Caucus strategy planning breakfast to attend, committee meetings to sit through, and lawmakers to buttonhole to support for legislation he is sponsoring. He has five meetings scheduled with constituents, one with a lobbyist and one with a Republican committee chairman.

It’s as if Brutus has two days instead of two years to accomplish the goals he set out for himself and the community he newly represents. But considering how hard it was to get here, and how long it took, he figures he has some serious catching up to do.

“I’m still learning, but after that I should be able to effectuate some real change,” he says.

To some people, Brutus’ mere presence in the state capitol is a sign of real change. This hall of political power seemed a world away from Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood, eight hours by car and home to Brutus’ core constituency of political exiles, economic refugees and immigrants working menial jobs.

That all changed last November when he became State Representative Brutus, the first Haitian-American elected to the state legislature and only the second Haitian immigrant nationally to hold an elected state office.

Brutus’ win was a crowning achievement, not only for the candidate, who sought public office twice before and lost, but for Haitian activists long frustrated with not having one of their own among local and state political power brokers. His victory is seen as a significant step in a once slow march to political self-sufficiency. Lately though, that march has seemed more like a sprint as Haitian-Americans around the country run for public office — and win.

BECOMING AMERICAN: Haitian immigrants increasingly are becoming U. S. citizens. This chart shows their recent naturalization rates.

| Year | Total U.S. | Florida |

| 1988 | 2,350 | NA |

| 1989 | 3,692 | 1,232 |

| 1990 | 5,009 | 1,805 |

| 1991 | 4,436 | 1,475 |

| 1992 | 3,993 | 1,191 |

| 1993 | 5,202 | 1,256 |

| 1994 | 7,997 | 2,026 |

| 1995 | 7,876 | 1,459 |

| 1996 | 24,556* | 10,036* |

| 1997 | 15,667 | 4,571 |

| 1998 | 10,168 | 3,245 |

*Reflects a nationwide surge in naturalizations by immigrants in response to a 1996 immigration law that denied certain government benefits to non-citizens.

Source: U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service

Nowhere is this trend more apparent than in South Florida, home to about 150,000 Haitian immigrants. Two Haitian-Americans now sit on the five-member City Council of El Portal, a small village of about 3,000 people, wedged between Little Haiti, located just a few blocks from Miami’s downtown, and Miami Shores, a town in the northeastern part of Dade County. North Miami, a municipality of almost 60,000 residents, about half of them Haitian, elected its first Haitian-American councilman in 1999 and its second this year after three Haitian-Americans ran for an open seat on the City Council. The five-member City Council now has a Haitian majority since gaining its first Haitian-American mayor, a Republican, who ran for the seat two years ago and lost.

Coming to America: There are about half a million Haitian immigrants living in the United States, most of them in large Haitian enclaves in Miami, New York, Boston and Chicago. The U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service estimates that at least 105,000 of them are undocumented and are living here illegally. Haitian organizations put the Haitian-American population at one million when the American born children of Haitian immigrants are counted.

Although large scale Haitian immigration to the United States didn’t begin until the 1960’s, Haitians have been coming to this country since at least the 1930’s.*

Below are the number of Haitians who immigrated here legally.

| Year | Haitian Immigrants |

| 1931-1940 | 191 |

| 1941-1950 | 911 |

| 1951- 1960 | 4,442 |

| 1961-1970 | 34,499 |

| 1971-1980 | 56,335 |

| 1981-1990 | 138,379 |

| 1991-1994 | 80,867 |

| 1995 | 13,872 |

| 1996 | 18,185 |

| 1997 | 14,941 |

| 1998 | 13,316 |

*The INS did not start separating out Haitians by country of origin until 1932. Prior to then, they were simply counted as Caribbean immigrants.

Source: U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service

“Clearly, clearly the community is evolving,” says Brutus. “Ten years ago, we could not have even thought about achieving this.”

The political activity reflects a shift in thinking among the nation’s half million Haitian immigrants. Where once their interest in American politics mainly revolved around immigration issues and U.S. policy towards Haiti, they are now taking an interest in domestic affairs such as affordable housing, economic development, health care and tax policy.

Now, after decades of building lives and developing ties in the United States, many have discarded idealistic but unrealistic dreams of returning to their troubled homeland which is still mired in deep political and economic instability 16 years after the collapse of a brutal, dictatorial dynasty. Instead, Haitians are adopting the hyphenated identities they once shunned, becoming naturalized citizens in record numbers and voting in local and national elections.

According to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, close to 88,000 Haitians became U.S. citizens between 1988 and 1998, the most recent years for which figures are available. Almost 30,000 of those naturalized during that period were in Florida.

“We strongly want to be part of the American political process and not make the mistakes our parents made 20 years ago,” says Francois Leconte, 37, founder and president of the Minority Development and Empowerment Inc. Haitian Community Center, which runs social service and economic development programs in Fort Lauderdale. “They never became U.S. citizens. They never took part in the political system. They died here thinking they were going back to Haiti but never made it back. Let’s face it, most of us aren’t going back.”

Many Haitian-Americans believe that with Brutus, the community finally can move out of the shadows of the larger, more politically influential and economically powerful Cuban exile community and emerge as a potent voting block in their own right. They also hope to become less reliant on black American elected officials who, despite their sensitivity to Haitian causes and their racial allegiances, can’t fully relate to being an immigrant with a distinct language and culture.

Brutus, a Democrat, will represent district 108, a swath of Northeast Dade that includes the affluent residents of Miami Shores and the working poor of Little Haiti. The district also takes in several other towns including El Portal, Biscayne Park, North Miami and some unincorporated areas of the county.

The district has sizable Haitian and African-American neighborhoods and enclaves of gays, senior citizens and Hispanics. The largely Democratic district is 80 percent black, and of those, about 60 percent are Haitian-Americans, 40 percent of them registered voters.

While North Miami and Miami Shores have a growing Haitian middle class, Little Haiti, the symbolic heart of the Haitian community and the center of Haitian political activism, has one of the lowest income levels in Dade County. The median household income was $14,142 in 1990, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The average per capita income was $5,693, compared to $10,000 for the City of Miami and $30,000 for the county. There are no major businesses within its borders. Crime and unemployment are vexing problems. Large portions of the residents lack health insurance. Improving economic conditions there may prove to be one of Brutus’ greatest challenges.

“Turning around years of abandonment and neglect is a daunting task,” he says, “but I understand the necessity to succeed in that regard. Doing that would be the crowning achievement of my tenure.”

Already, Brutus and a senator from his district are pushing to bring a medical clinic to Little Haiti where residents can pay for services on a sliding scale based on income.

Though he clearly symbolizes the aspirations of his Haitian-American supporters, Brutus stresses he will not focus solely on Haitian constituents, a charge that his campaign opponents exploited in the 1998 and 2000 races and that Brutus had to counter repeatedly.

“The media has seen fit to sort of taint my candidacy as a Haitian candidacy, to say that I’m going to be a representative for Haitians only,” he said in a stump speech during the campaign. “Look. I was born in Haiti. I’m proud to have been born in Haiti, but I’m an American. I’m here and I cannot say that I am going to run a campaign for Haitians only.”

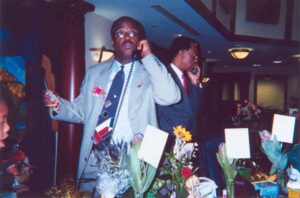

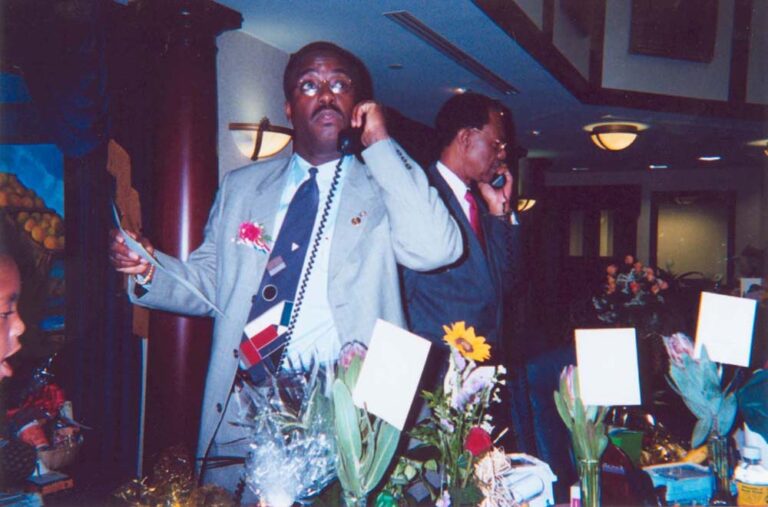

Still, Brutus could not have won without the Haitian vote. He campaigned hard in the Haitian community and on Creole language radio and cable television access programs. Supporters held voter registration drives and an army of volunteers canvassed Haitian neighborhoods to get out the vote. A good portion of the $75,000 he spent on his campaign came in $10 and $20 donations raised at soccer games and other low budget community events

Brutus went on a Haitian public affairs cable television program and, using sample ballots and an actual voting booth as props, did a step-by-step demonstration for first-time voters. He won with 81.7 percent of the vote, with near perfect turnout in Little Haiti. Brutus lost the 1998 contest by 51 votes, largely because of confusion among first-time Haitian voters who invalidated their ballots by voting for both candidates.

“They see me as a guy who can represent everyone, but who they can still call ‘our guy,’” he says of his compatriots.

Three years ago when Brutus and other Haitian-Americans were running for seats on local school boards, city commissions and in the legislature, community members dubbed the budding political activism the “Haitian Sensation.” All the candidates lost but they left an indelible mark on the local political scene.

Now that several Haitian-Americans have won office and more are running, Haitians speak in lofty terms of “our political movement” and point to Massachusetts State Representative Marie St. Fleur, a Haitian immigrant, as proof of their emergent national clout.

Calling this trend a political movement may be an overstatement, but there is ample evidence the political landscape is being altered by Haitian immigrants living in South Florida. In the process, they say they are shedding the image of their community as a collection of unschooled, dirt-poor, boat people and gaining it recognition and respectability.

Six years ago, there were no Haitian-American elected officials in South Florida. Today, there are five Haitian-Americans in public office. For a time, the five-member El Portal City Council had a Haitian-American majority until one lost re-election.

Political activism also has spread north to Broward County among Fort Lauderdale’s smaller Haitian population. Last year, a Haitian man ran for a state House seat and another campaigned for a city commission seat in Sunrise, a town known more for police corruption scandals than immigrant politics. In 1998, a Haitian man ran for the state Senate and a Haitian woman ran for the Board of Education. So far, all these candidates have lost.

To listen to political watchers, it’s just a matter of time before a Haitian-American is elected to the Miami-Dade County Commission, now dominated by Cuban-Americans.

“Being from Haiti, we always believed that in America, if you work hard and play by the rules, you could accomplish anything,” Brutus says. “This is a coronation of that mantra.”

Forty years after Haitian immigrants started arriving to the United States in large numbers, and 20 years after the first waves of Haitian refugees started coming to Florida shores, a new generation of Haitian-American political leaders is emerging. Some came as children with their parents, while others were born here. Many were educated in American colleges. They are politically astute and media savvy. They have high-powered jobs and outsized ambitions.

“If you want to have any impact, you can’t be one of those people who sits on the sidelines,” says Alain Valias-Jean, who was 26 years old when he ran for a state House seat last fall and lost.

Valias-Jean, who was born in Brooklyn, is a former congressional aide who now works as director of government and public affairs for the newly elected Broward County Supervisor of Elections. He says he knew his heart was in politics since an eighth grade civics class, when he tried to get his classmates to support Dick Gephardt’s 1988 presidential bid.

“After my experiences in Washington, I can say with complete certainty that if you’re not at the table when the decisions are made, your agenda all but goes nowhere,” he says.

Valis-Jean is a member of the Leadership Circle PAC, a political action committee founded three months ago by Leconte of the Fort Lauderdale Haitian Community Center and six other Haitian-Americans. They plan to assist emerging Haitian-American political leaders and support those already in office. They also plan to help non-Haitian politicians who work on behalf of Haitian-American interests.

Not surprisingly, there is widespread speculation that a Haitian-American will be elected to Congress this decade. And Brutus, who lost a 1994 bid to become Miami’s first Haitian-American county court judge, is being touted for the job.

“In 2004 when the Democratic Party starts plotting races, they’re going to have to come to us who won office instead of the self-appointed leaders in the community,” says Brutus, 44, a self-assured — some say arrogant — trial attorney.

Brutus has proven to be a curiosity around the state. In early March, at the start of the legislative session, a couple of lawmakers were overheard talking about “the gentleman from Haiti” and scanning the house floor to get a look at him. Local newspapers have run glowing profiles of Brutus, focusing on his immigrant roots and his up by the bootstraps success story.

Last November, after swearing-in ceremonies for new legislators, the Speaker of the House singled out Brutus and noted his status as the first Haitian-American State Representative. All eyes turned to Brutus as the room rang with applause and people rose to their feet. Brutus, visibly moved, stood up and waved, as his wife and law partner, Yolly Roberson, beamed proudly. Also in the audience were Ossman Desir, North Miami’s first Haitian-American City Councilman and other Haitian supporters.

Afterwards, Brutus was interviewed by a news crew from Island Magazine, a popular Miami Haitian public affairs cable television program which spent the day following him around.

“I stood there representing the Haitian nation, all black people, all immigrants, all poor people…who dreamed of the day,” he told his interviewer, adding that the standing ovation was not just for him but for the Haitian supporters whose votes carried him to the State House.

That so many Haitians lined up behind Brutus’ campaign was extraordinary considering the political infighting that once characterized the community. Not long ago, there was a palatable intolerance in Haitian Miami for political differences and inconsistent adherence to democratic principles, a byproduct perhaps of having lived under successive dictatorships in Haiti.

Death threats, slanderous comments in Haitian newspapers and radio programs, and boycotts of businesses owned by people who held politically unpopular views were not uncommon. Two Haitian-American radio broadcasters were murdered in Miami in 1991 for speaking out against businesses supporting the military regime that ousted Haiti’s first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Another broadcaster was gunned down in 1993 for doing the same thing.

Haitian-American politicians and activists say the community has matured and is more tolerant and politically sophisticated.

Newly elected North Miami mayor Josephat “Joe” Celestin, 44, who was the sole Republican among the Haitian candidates, personifies this political coming of age. A businessman who owns a contracting company, Celestin ran for mayor in 1999 and lost. He ran for a state House seat as a Democrat in 1996 and got just 10 percent of the vote.

In 1998, Celestin became a Republican and ran for the state Senate and lost. Back then he was a brash upstart running against a better financed, better-known, black American Democrat named Kendrick Meek. Meek is the son of Congresswoman Carrie Meek, who is popular in the Haitian community because of her history of championing Haitian political causes. During the campaign, Meek argued that Celestin was pitting Haitians and black Americans against each other, threatening their long working relationship and weakening the black vote.

Leoni Hermantin, executive director of the Haitian-American Foundation, Inc., never bought that argument. She voted for Celestin anyway.

“I knew Joe was going to loose and that Kendrick was the better candidate,” says Ms. Hermantin, whose organization provides social and economic development programs in Dade County. “But I knew we were at this critical juncture where it was important that the Haitian electorate’s potential as an emerging voting block be noticed and taken seriously.

“Had we, as a block, supported Kendrick Meek, it would have gone unnoticed. If 10,000 Haitians vote for him and he wins with 30,000 votes, it doesn’t say the same thing. It was when this renegade, Joe, started talking about Haitian political empowerment that people started to see Haitians as a voting block.”

Celestin says this time around he set his sights lower because ” I think it would be better to run locally first because you can show people what you are capable of and then move on.”

Still, it was his first run for public office that set him on his long term political strategizing. The day after his defeat, he started plotting a comeback. He purchased a voter roll of two million names and marked each voter with a Haitian-sounding surname and then created a database of those voters to gauge Haitian geographical strongholds district by district.

“I wanted to see where we had a strong base and what races we needed to put a Haitian challenger in,” says Celestin, who immigrated to the United States at age 22.

After analyzing the voter rolls, Celestin formed a Haitian-American Political Action Committee and organized a meeting of some half dozen politically active and prominent Haitian-Americans, including Brutus, to map out which districts they should run in for local and state offices.

“Politics is a science,” he said, a smile on his face. “You need to have people on both sides of the table to get anything done.”

In the last two and half years, Celestin kept himself visible, serving on North Miami’s Planning Commission and on the Board of Adjustment. He founded the Haitian-American Republican Club, which now claims 3,000 members and is charted by the state Republican Party. He conducted “voter education classes” on a Haitian radio talk show called Koze Politik, or Political Talk, from 1997 until 1999. And he regularly attends county naturalization ceremonies (18, by his count) to meet newly minted citizens and encourage Haitians to fill out voter registration forms, which he keeps in large supply.

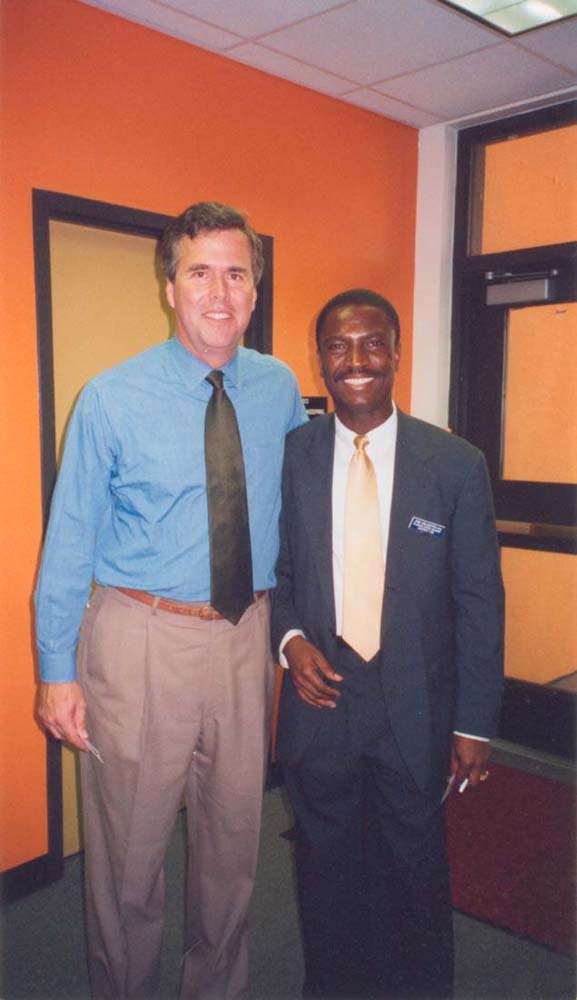

Last fall, Celestin and Sidney Charles, the vice chair of the Republican Club and a member of the state Republican Party committee, organized a gathering of Haitian-American Republicans to officially endorse George W. Bush for president. Jeb Bush attended. During Celestin’s unsuccessful 1999 race, a letter written by Gov. Jeb Bush was mailed to North Miami residents urging them to vote for Celestin.

“You have a unique opportunity to make Florida a better place to live, work and raise a family by electing Joe Celestin as your mayor,” the letter states. “I have long admired Joe Celestin for his commitment to the community of North Miami. Joe’s leadership, his strong business background and education credentials will make him an excellent mayor.”

Celestin, who has a reputation for being tactless and a penchant for exaggerating, also is careful to nurture his ties to the overwhelmingly Democratic Haitian-American community, even though the mayor’s race is non-partisan. Last year, Celestin spoke at a fundraiser for Brutus and said he would ask every member of the Haitian-American Republican Club to vote for Brutus. He also donated $150 to Brutus’ campaign.

It was a telling moment of how far Haitian politics had come in Miami when a Haitian Republican could stand in a sea of Haitian Democrats, speaking on behalf of a Democratic candidate — especially considering the awkward history between Brutus and Celestin. The two men nearly came to blows in 1998 when they publicly argued and shoved each other during a city budget meeting. They had to be pulled apart by Miami police.

“This is something we would rather not talk about,” Celestin now says. “It’s not something we’re very proud of. We became friends the same day, we apologized the same day, we worked it out.”

Extending such a visible olive branch at the fundraiser was a smart political calculation by Celestin considering Brutus’ popularity in the community,

“We may not see things the same way but we have certain things in common when it comes to the Haitian community,” Celestin says. “Besides, it’s not an issue of party, there’s a movement behind the Haitian community.”

With Brutus firmly in place at the State House, the focus shifted to Celestin.

The last time he ran for mayor, he got 45 percent of the vote, more than the other four candidates but less than 50 percent plus one he needed to prevent a runoff. He lost the runoff by 438 votes. He predicted 2001 would be his year and he was right. He was sworn into office last May.

So what happens now?

“The struggle continues,” he says.

©2001 Marjorie Valbrun

Marjorie Valbrun, a Wall Street Journal reporter, is investigating Haitian immigrants’ political activism during her Patterson year.