Tlacuitapa, Mexico — For a dozen days a year, Tlacuitapa, a depressed Mexican village so small and isolated that it doesn’t appear on any official map of Mexico, comes to life. That’s when hundreds of former residents now living in the United States come to Tlacuitapa to connect with the family members — mostly elderly grandparents and young children — they’ve left behind, to fix up houses which stand empty for most of the year, and to taste a life they miss only for its memories.

But the rest of the time, Tlacuitapa has the feel of a ghost town. The town square, the heart and soul of any Mexican village, is almost always deserted. On a recent afternoon, an old woman hunched over a walker peered onto the square from an open doorway, while schoolchildren carrying backpacks walked on a side street after trading pesos for candy at La Primavera, one of two tiendas facing onto the square.

The emptying out of Tlacuitapa has taken place over a half century, beginning in 1943 when town residents began migrating to the U.S. as agricultural workers in the bracero program, which over a 20 year period brought 5 million contract workers to the fields of California and other agricultural regions. By an accident of history, one Tlacuitapeno found work in a nursery in Union City an hour’s drive south of San Francisco. At that time, it was largely a farming community made up of lettuce and strawberry fields. Today, tract homes have taken over the fields, and it prospers as a bedroom community on the edge of Silicon Valley. Today hundreds, possibly thousands, of Tlacuitapenos live in Union and Union City and surrounding communities. Many have bought homes within blocks of each other, recreating the life they left behind in Tlacuitapa, but living far more comfortably.

The rock-solid links between places like Tlacuitapa and Union City have been largely ignored by lawmakers and policy makers in the United States in their so far fruitless efforts to deter migration between the two countries. Each decade brings a fresh effort: Operation Wetback in 1951, when tens of thousands of Mexican migrants were rounded up and sent back across the border; ending the bracero program in 1962, with the expectation that the migrant workers would go home; the imposition of fines on employers who hires undocumented workers; and the near-militarization of the border beginning in 1994. But, like hardy desert cacti, the migratory networks are so firmly in place that they appear to be immune to government attempts to uproot them.

One morning, 16-year-old Tania Marquez greeted a visitor in the small courtyard between the wrought iron gate and the front door of their house in Tlacuitapa. Dressed in jeans and a T-shirt with a slogan “Limit Congressional Terms,” clearly brought back by one of her U.S.-based relatives, she could easily pass for a typical American teenager. Tania has finished her primaria and secondaria — the U.S. equivalent of elementary and junior high school. Like most teenagers here, all she does is dream of when she can go to the United States.

There is no high school in Tlacuitapa itself. To get there, Tania would have to be driven by each day to the closest one in Lagos De Moreno, a half hour away. In a village where selling milk and cattle is the main industry, those costs are a sufficient disincentive, and almost no Tlacuitapenos ever make it to high school, let alone leave it with a diploma.

But it is not just a matter of finances; it is also one of desire. Eloisa Marquez says she is helpless to force Tania to go to school. Within the immigration-focused ethos of the village, graduating from secondaria, not the preparatoria, has become the rite of passage to the U.S. Maurilio Jr., the Marquez’ oldest son, has already headed north to join other family members, staying in a room in the comfortable tract home that Eloisa’s brother Eligio owns in Union City. The 19-year-old also has been able to land a job in construction, benefiting from kinship networks that act as an efficient employment agency as well.

Those left behind in Tlacuitapa feel obligated to explain why they are still here. In the old days, Eloisa says, women did not go the United States. That’s why she’s still here. Her husband Maurilio Marquez Sr. actually lived in the U.S. for many years. He now owns cows and runs what passes for the town’s only gas station — a crumbling adobe shack on the edge of the village. The gas is stored in an oil drum. When a customer arrives, he pumps the gas with an old hand pump into a plastic bucket. With the help of an overized yellow plastic funnel, he pours the gas into the gas tank.

Sitting on a rock outside the gas station, he eagerly tells his sad story. Life was hard in the U.S. and he struggled to make ends meet. He eventually began using drugs — cocaine — and was convicted and sentenced to three years in jail. When he got out he was immediately deported back to Mexico. But he still has dreams of escaping Tlacuitapa. For him and others, the way out is not nearby Lagos de Moreno, or the larger city of Leon, or even Mexico City. The choices is to be in Tlacuitapa or in the United States. There is nothing in between.

“These villages, which have so many traditions, now believe that the only way out of poverty is to go the U.S.,” laments Jorge Dorand, an eminent anthropologist at the University of Guadalajara two hours to the south. “Who remains behind are the weak and the rich.

The prospect of the immigration has immobilized people. They think that over there is everything, but here there is nothing. So what’s the point of working here? And the parents say the same thing. And they are right.”

In February 1998, the town was shaken by the tragic deaths of seven local teenagers as they tried to make their way across the border. Almost everyone in the town turned out for an emotional mass funeral service for three of the youngsters. The bodies of the others have never been found.

But neither the tragedy, nor the challenge of travelling 1000 miles to the border, of traversing triple steel fences, getting passed a line of 8000 Border Patrol agents, and evading high tech surveillance devices, has done anything to discourage Tlacuitapenos from fleeing north. “I feel sorry about those guys who died, but it hasn’t stopped anyone from going,” said Luis Marquez Gonzalez, the town’s delegado, the closest thing Tlacuitapa has to a mayor. A short, stockily built man wearing a blue shirt and jeans, with white leather shoes, he blames the deaths on the carelessness — descuidado —-of the young men themselves. They were drinking, he says, and they also made the mistake of choosing a particularly dangerous route through the desert in Coahuila, trying to pass through Ciudad de Acuna on the Texas stretch of the border.

In fact, Marquez said, more people are going than ever before. In the past, it was only men who went north. Now increasing numbers of women are going as well.

“They get married, and they take their wives,’’ he said “And then they come back, and take their daughter, or the brother will come back to fetch his sister.”

The only reason Marquez is in Tlacuitapa is that he returned here eight years ago after 28 years in the United States. He left in 1963 at the age of 16, living mostly in Los Angeles where he worked as a plumber. Now a U.S. citizen, he lives in his comfortable Tlacuitapa house with its bright blue exterior wall which stood vacant for the better part of three decades while he was in the U.S. Over the years he upgraded the house, remodeling the kitchen and laying expensive floor tiles in every room.

But his 22 and 23-year-old sons live in Los Angeles, where one is a roofer and the other works in construction. “It’s the case of the dollar,” he says, explaining why he believes as many as 90 percent of the people in his village eventually make their way to the U.S. If you’re lucky enough to get work in the town — as a garbage collector or a gardener for the municipality, for example — you earn 210 to 220 pesos, or $20, a week. In Leon, you may be lucky enough to be paid 300 to 350 pesos a week —but still less than your day’s work in the U.S. earning the minimum wage.

The town, he laments, is in an economic wasteland. There are no textile or auto plants, shoe factories, or any industries of any kind. So many people have left that Marquez says he can’t find young men to do even odd jobs around the town. “How much are you paying?” they ask me,” Marquez says. “When I tell them, they say, ‘I can make much more in the U.S.’” Government programs, he says, are too limited in scope and are riddled with corruption to do any good. Procampo, the government’s main rural assistance program, is supposed to subsidize feed for cattle, but in Tlacuitapa only about 40 farmers get around $55 a year in subsidies. In any case, Marquez complains, “they just give it the rich guys, and also too people who don’t even have any cattle.”

What keeps the town going, he says, is the continuous influx of money or remittances sent by family members across the border. “If it wasn’t for the remittances, every person in this town would be up north” argued Rudolfo Tuiran, the respected head of the National Population Council, which studies demographic trends between the two countries.”

A few blocks away Gonzalo Amezquita Marquez and his wife Elsa are an exception to the inexorable northward tide. They are one of the few families to have actually returned with their families after years in the United States. Gonzalo and his wife lived for 10 years, mostly in Chicago, where he worked for a landscaping company. They returned because they thought Tlacuitapa would be a better place to raise their children — all of whom were born in the United States — free of gangs and other hazards of urban life.

Gonzalo, whose boots are caked with mud, and whose T-shirt carries the admonition “Hang Loose,” is the closest thing to an entrepreneur you’ll find in Tlacuitapa. He owns 70 head of cattle and 40 cows, and he buys and sells houses and pick-up trucks. But despite his apparent successes, he has difficulty making ends meet. The North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement, he complains, has opened the door to imports of meat and powdered milk. That, along with price fixing and corruption, has depressed the prices he can get for his products. If he’s lucky, he can get 2 pesos per liter of milk. That’s less than it costs to buy a liter of Coke, Elsa adds in a conversation in the living room of their large, sparsely furnished home.

In a major setback to their efforts to establish themselves here, they were unable to stop their eldest son, now 16, from going back to Union City as soon as he finished secondaria. As a U.S. citizen, he had no trouble getting across the border. He now lives with one of his father’s brothers, and was easily able to land a job in a meatpacking plant, despite being a minor.

“He doesn’t like the campo, the countryside,” Elsa says.

“He wants an easier, more comfortable life. Here we don’t even have one day of rest, because the cows don’t wait for you. You can’t even take vacation, to go to Acapulco for a day or two. All you can do here is graze the cattle, and milk the cows. The young people have nothing else to do, and they get bored. And they want money and they don’t have money here.”

Making matters worse, their son returned to the U.S. with a friend who used to help milk the cows. Without them, their life has become even more difficult. “Now me and my husband are doing all the work,” she said. At the same time, she accepts that they were powerless to stop their son from going. “If we opposed him, he would have found his way there anyway, and it is better that he go with our consent.”

One consolation is that he will have a vast extended family to keep an eye on him. All Elsa’s six brothers and sisters are in the United States. Her brothers Cruz, Ramon, and Enrique live within a few blocks of each other in Union City, where each works for a chain link fence company. Her sister, Blanca, lives a mile away from them. And her mother Rosa, the matriarch of the family, returned briefly to Tlacuitapa after decades in the U.S. to take care of a granddaughter, but recently returned to live permanently with her children in Union City. Gonzalo also has three siblings there, and another two in Chicago.

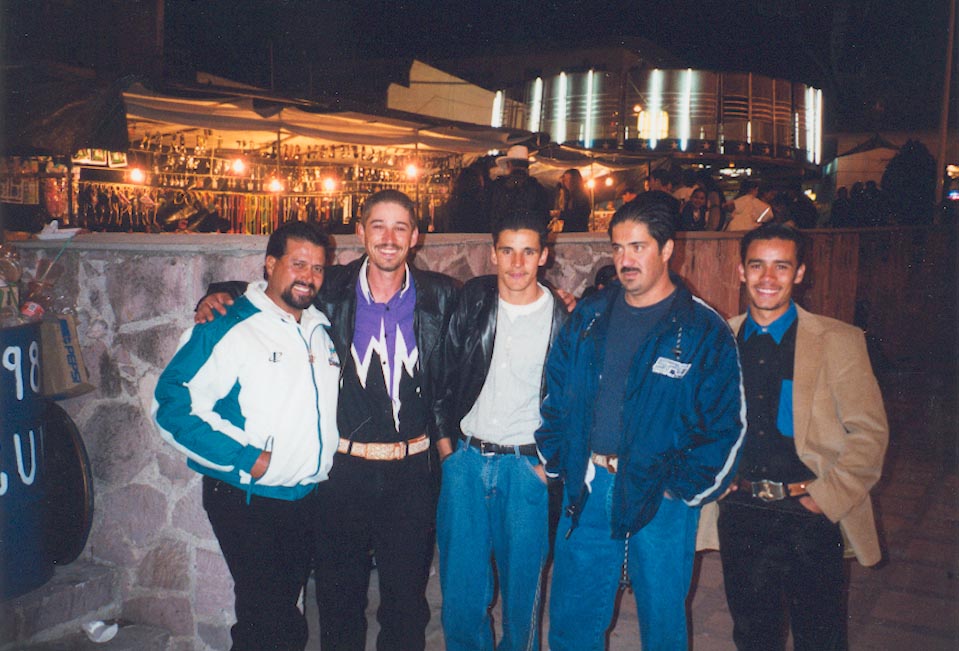

Now they are trying to decide whether they should return to Union City as well, which in many ways has the feel of a vibrant Mexican community much more than Tlacuitapa does. Almost every weekend there are fiestas in the local park, baptisms, quinceaneros, weddings, and baby showers, attended by dozens, and sometimes hundreds, of migrants from Tlacuitapa and surrounding villages. The men wear their customary white straw hats, blue jeans with a leather belt and silver buckle, and brown leather boots. The women cook posole, caldo de pescado, and other traditional dishes from Tlacuitapa.

The standard view of migration is that there are “push” factors in Mexico — a poor economy, a devalued peso, lack of jobs — and “pull” factors in the United States, primarily the lure of jobs, that keep the migratory stream going. But the kinds of ties that exist Tlacuitapa and Union City suggests that the migratory ties themselves contribute to additional migration, independent of what “push” or “pull” factors may exist. “Networks that connect people to their communities of origin create the conditions that the migratory movement will continue and perpetuate itself,” says Rudolfo Tuiran.

With 8 million Mexicans living in the U.S., there are similar ties between literally hundreds of communities in Mexico and in the U.S. Those migratory networks will be impossible to break, if only because the more people come, and the longer they stay, the stronger those networks become.

©2001 Louis Freedberg

Louis Freedberg, a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, studied immigration issues during his Patterson year.