El Paso, Texas—Wire fencing encases the sides of the Rio Grande where the river slices through El Paso on the U.S. side and Ciudad Juarez on the Mexican side of the border. Its purpose: to keep out illegal migrants who each year routinely swim across to seek their fortunes in the United States. Today, as far as the eye can see, the concrete canal is empty of people, an apparent success story in the three billion dollar attempt to shut down one of the longest — and busiest international borders in the world.

It is in El Paso that an obscure Border Patrol chief, Sylvestre Reyes, had a simple but original idea. Instead of having his agents scurry through the bush to apprehend migrants one by one after they had crossed the river, why not post agents along the river at quarter mile intervals in an effort to deter them before they even tried to cross?

In October 1993, Reyes implemented his vision, calling it “Operation Hold the Line.” Within days, the flood of immigrants that usually could easily overcame the weak currents of the Rio Grande slowed to a trickle. Initially, Reyes’ approach ran so counter to the prevailing philosophy of the Border Patrol that he met fierce resistance from his superiors in Washington. But soon his ideas were picked up by the Clinton Administration, prodded by Congress, and implemented all across the border.

“It is a strategy that worked,” said Reyes, who has parlayed his successes in El Paso into a seat in the House of Representatives in Washington D.C. “You’ll never seal the border completely. The Berlin Wall proved that. But we believe we can be 85 percent effective.”

So effective, in the eyes of Congress and the Clinton Administration, that Operation Hold The Line morphed into Operation Gatekeeper, on the western edge of the border in San Diego, to Operation Rio Grande in Brownsville on its eastern edge. According to a five part strategy announced by Attorney General Janet Reno and Immigration and Naturalization Service Commissioner Doris Meissner in February 1994, the purpose was “prevention through deterrence” — to make it “so difficult and so costly to enter this country illegally that fewer individuals even try.”

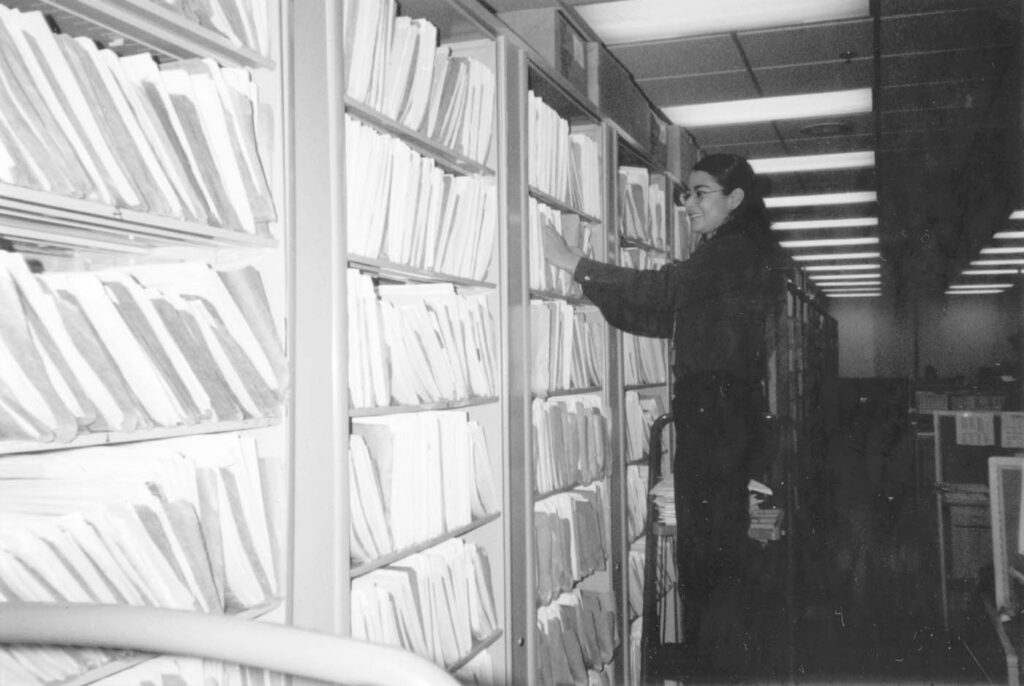

Between 1993 and 1998, the budget of the Immigration and Naturalization Service mushroomed from $1.5 billion in 1993 to nearly $3.97 billion, by far the greatest increase of any other federal agency. The number of agents on the Southwest border rose more than doubled, from 3,400 to 7,353. Along with it there has been massive increase in the use of ground sensors, helicopters, and border lighting, along with new technologies like night scopes and computerized fingerprint identification systems.

But, six years after the strategy was initiated, there is scant evidence that the flow of illegal migrants has slowed. Census figures indicate that there are at least as many illegal immigrants in the U.S. —some 5 million—-as there were in 1994. The number of new illegal immigrants who settle permanently in the U.S. each year continues to grow at a pace of between 275,000 and 300,000 each year.

What has happened is that migrants are having to try more often to get across without being apprehended, and are using different routes to do so. In fact, there is reason to believe that the new border controls have inadvertently interrupted long standing patterns of circular migration, in which large numbers of migrants, especially those from Mexico, moved back and forth across the border, staying only temporarily in the U.S. Today, the new border controls are having the unintended consequence of encouraging migrants to stay longer in the U.S. than before.

“Although the strategy has made certain areas of the Southwest border more difficult to cross,” a May, 1999 General Accounting Office report concluded, “large numbers of illegal aliens continue to make their way into the U.S.” In addition, the report cited INS figures on apprehensions at the border which indicate “a continued shift in illegal alien traffic from traditionally high illegal entry points to other areas.”

These are areas where they run the risk of losing their lives. Until Operation Gatekeeper went into effect, most deaths on the border were on the freeways outside of San Diego. Now the deaths-—254 known fatalities in 1998—appear to be taking place in desert areas like those near Mexicali east of San Diego, where temperatures routinely reach 120 degrees.

Even Immigration and Naturalization Service Commissioner Meissner concedes that securing the border has been far more difficult than originally anticipated. “We expected geography to be our ally, and in fact people have been far more willing to cross in places that are formidable,” said Meissner. Driving them to cross, she said, is “the most fundamental human motivation that exists, which is to eat and support your family and survive and have a future.”

By far the most ambitious effort to secure the border has been at the boundary separating San Ysidro from Tijuana south of San Diego. At first glance the effort seems to be paying off. On a recent evening on a dark hillside on the border, a lone Border Patrol agent peered through his night scope— a device that can detect any living creature for miles around. In the distance, newly cleared expanses of bare earth illuminated by stadium style lights could be seen. The only movement detected by the night scope were four men pacing near the border fence some two miles away.

A few years ago these same hillsides were covered with hundreds, if not thousands, of illegal immigrants each night, scurrying through the bushes trying to evade frustrated agents. These days, at the Border Patrol station in Imperial Beach, just yards from where the border fence runs directly into the Pacific Ocean, agents complain of boredom, yearning to be transferred to livelier sections of the border.

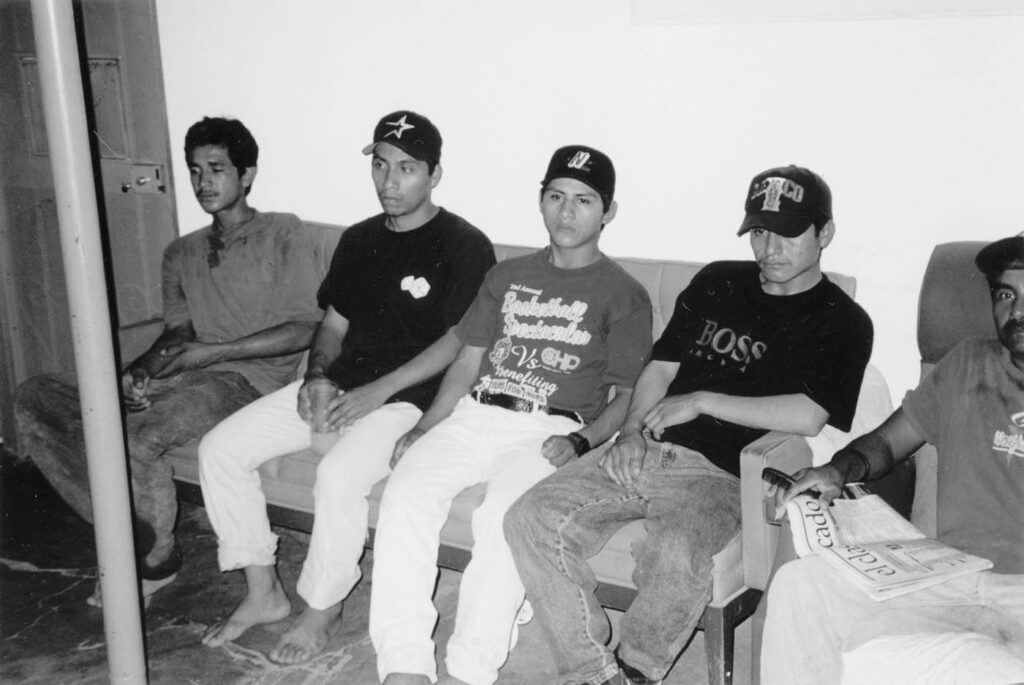

But even here, at the most defended section of the 2,000 mile long border, migrants have not yet given up. Cross to the Mexican side of the fence, and groups of mostly men can be seen huddling together alongside the fence, some hiding in drainage ditches, others sleeping or hanging out on mattresses, waiting for the best time to cross.

In one large drainage pipe, a dozen Mexican men were plotting their next attempt to cruzar la linea. From where they sat, they could see Border Patrol agents waiting in their white utility vehicles at regular intervals along the ridge across the fence, while bulldozers cleared the last remaining vegetation on the U.S. side. For an outsider, it was hard to imagine how anyone could cross here undetected.

But Jose Luis Ortega, the apparent leader of the group, said they were going to try again, for the fourth time that week. The 23-year-old slightly-built Mexican with shoulder-length hair had worked for five years as a construction worker in Temecula, a bedroom community half way between San Diego and Los Angeles. Nine months earlier, he had returned to visit his family in his home town of Tecate, a border town better known for its export of beer than migrants.

When he and his fellow travelers tried to return to the U.S. the previous week, they were apprehended three times by the Border Patrol, who put them on a bus and took them back to Tijuana. Each time they tried again to cross. Ortega said they were going to stay try for another week. And if they don’t make it? “We’ll head towards Mexicali, and try to cross there,” he explained, referring to the border town 150 miles to the east which has become a favorite crossing point for increasing numbers of migrants.

His story underscores the difficulty of trying to seal a border as long and as porous as this one. Shut down one section and migrants simply try to get in somewhere else.

Measuring illegal migration flows is by its nature an inexact science, which in turn makes it difficult to assess the success of the new border policy. Another is the number of apprehensions made each year by the Border Patrol — although apprehension data is notoriously difficult to interpret. Finally, interviews with migrants themselves give some indication as to how the new border controls are working.

Taken together, these sources provide no evidence that the border controls are deterring migration. Last year, for example, the Border Patrol apprehended 1.5 million migrants, compared to 1.2 million in 1993 and 980,000 in 1994. The increase strongly suggests that more migrants are attempting to cross than before.

What the new approach to the border has done is change the nature of the migratory flow significantly. In 1993, 68 percent of all apprehensions were made at the border near San Diego and El Paso; by 1998, only 24 percent of apprehensions were being made there.

Apprehensions did indeed declined precipitously in the San Diego sector— from 531,000 in 1993 to 248,000 in 1998. But during precisely the same period they soared at points further east where the border was less secure. Last year, for the first time, there were more apprehensions along the Arizona stretch of the border than in San Diego. (Apprehensions in Arizona have jumped from 92,639 in 1993 to 387,000 in 1998.)

As a consequence, Douglas, Arizona, an isolated, depressed town with a population of 56,000 on the edge of the Sonoran desert, has been transformed into the key staging ground in the war against illegal migration. For decades, the town coexisted peacefully with Agua Prieta, the neighboring Mexican town, with an even more run down appearance than Douglas. The fifty Border Patrol agents posted there caught fewer than 100 migrants a day. But after Operation Gatekeeper went into effect, apprehensions leapt to 300, 400, sometimes 1,000 a day. “It was chaos,” said Victor Colon, a Border Patrol agent who has been posted here for five years. “We were being overrun.”

To cope, the INS quadrupled the number of agents in Douglas to 300. Along the entire Arizona stretch of the border the number of agents increased from 281 five years ago to 1100 today. And the INS instituted many of the same techniques it used in San Diego, tracking migrants with night scopes, ground sensors and helicopters. Last August, it put the finishing touches on a five mile 12 foot-high fence between Douglas and Agua Prieta, separating two communities that had been linked like Siamese twins for more than a century.

On a recent night patrol, Colon spotted a bus about to leave the Douglas Super Shuttle, a bus company directly across the street from the brand-new pink Dennis D. Concini U.S Port of Entry building. Colon, whose parents are immigrants from Puerto Rico, boarded the bus and asked passengers for identification. More than a third could not produce the required documents, and a dozen passengers were forced to disembark.

One of them was a tired and dejected-looking Ephraim Espinoza, wearing a yellow and black checkered shirt and tattered pants. Nine months earlier, he explained, he returned to Lagos De Moreno, a picturesque town 1200 miles south of the border in Jalisco, to get married. Before that he had lived for 11 years in San Jose, California, mostly working in a Mexican restaurant earning $300 a week.

But back home he found could only earn one tenth of that — about $20 to $30 a week — through odd jobs and the sale of milk from his cows. Even his wife agreed he had no choice but go back to California and try to reclaim his old job.

In previous years, Espinosa explained, he would have flown to Tijuana, easily slipping across the border, and catching a bus from there to San Jose. But that was before Operation Gatekeeper went into effect. He had heard it would be easier to cross in Arizona, an assessment he is no longer sure of. Bu he vowed to try to cross again, if only because he had already spent $1300 for a coyote to guide him across the border. “You do what you can do,” said Colon philosophically. “At least it’s a helluva lot better than before. We’re not getting overrun.”

On the Mexican side of the fence, Mexican authorities have installed signs near the border fence cataloguing the dangers migrants face in the desert, a parched landscape dotted with organ-pipe cactus. “Peligro —Temperatura Extremas,” warns one sign. Another warns of “Corrientes Peligros” (dangerous currents), and yet another of “Animales Venenosos,” a reference to the scorpions, snakes and poisonous spiders that abound here. And in May, 1996 the Mexican government set up a nine person police unit known as the Grupo Beta to try to protect its citizens from some of the most obvious hazards.

On this day, Maria De La Paz Reyes, the coordinadora of the unit, headed out on her daily patrol along the Mexican side of the fence. Whenever she or her colleagues came across a would-be migrant, they gave them cards listing the telephone numbers of Mexican consulates on the U.S. side of the border. She warned them not to wear valuables like watches — and to carry enough water. Dressed in casual clothes, wearing sneakers, and carrying small backpacks, most seemed woefully unprepared for the journey.

In Agua Prieta itself, men and women hang out on the sidewalks in front of rundown hotels with names like Hotel San Francisco, Casa Huespedes, and Hotel Frontera. Many of the hotels, several directly across from the new fence, have opened in recent months in response to the new demand for accommodations. “I don’t think it was reduced the number of crossings,” said Reyes, pointing to the fence. “They are just going to go to the end of the fence and try to cross there.

Some supporters of the U.S. border strategy say it is far too soon to assess its long term impact. Representative Lamar Smith, R-TX, the chairman of the House Subcommittee on Immigration, believes that until the INS reaches its full compliment of 10,000 agents prescribed by the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, undocumented migrants will continue to cross.

“We hope that doubling the number of Border Patrol agents will cut illegal immigration in half, but we will have to wait for four or five years before it will have that kind of impact,”’ said Smith, one of the strongest advocates of restricting immigration in Congress. “We will always have people trying to come into the country illegally. We will never stop it entirely, but we do hope to reduce it substantially.”

But 10,000 agents may not be enough to do the job, according to researchers at the University of Texas at Austin. The university’s Center for U.S. Mexico Border Studies estimates that 16,133 agents would be needed to reduce the flows achieved in El Paso and San Diego. That’s as many as are currently deployed. The INS already is having difficulty reaching its 10,000 target, because of the difficulty of recruiting and training such large numbers of agents and keeping them long enough before they resign from boredom or dissatisfaction with low salaries.

Now INS Commissioner Meissner argues that equally important to controlling the border is doing something about what is attracting migrants in the first place: the lure of jobs, an opinion shared by a wide range of immigration experts. “You can’t totally do the job at the border,” she said. “It must be coupled with workplace disincentives to eliminate the siren call of jobs just across the border.”

In the meantime, leaders of some border communities are trying to persuade the federal government to call off its border wars. Ray Borage, the mayor of Douglas, wrote to President Bill Clinton, telling him that the U.S. has failed to recognize the economic pressures driving hundreds of thousands of Mexicans to enter the United States illegally.

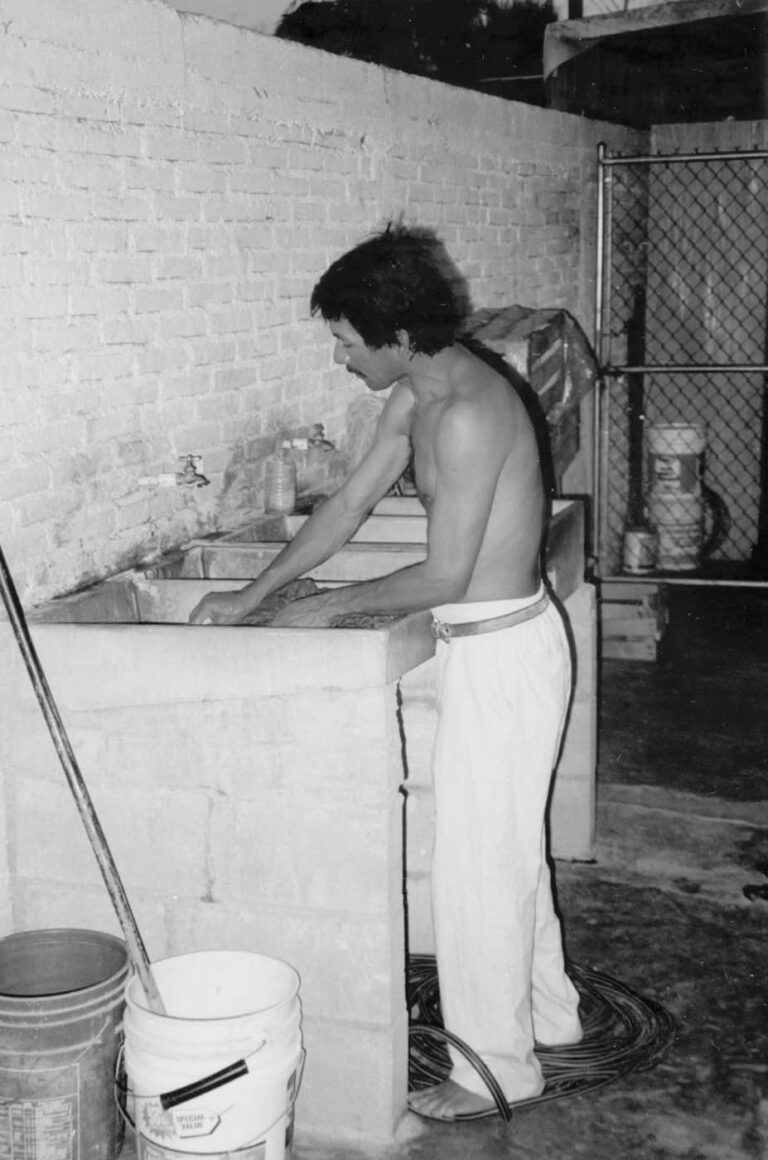

“Despite increased law enforcement, many of them will eventually find work with farms, meatpacking plants, hotels, motels, resorts, factories and other employers,” wrote Borage, who worried that his once peaceful town has been transformed into a Mecca for illegal immigrants. “These people are occupying jobs that people in the United States simply don’t want and will not do.”

©2000 Louis Freedberg

Louis Freedberg is a Washington correspondent for the San Francisco Chronicle, is studying how immigration is changing America.