“You’d always know in the pen when somebody got the L note [A life sentence]. It’s the one time a man can cry in prison. Being sent back to Haiti…it’s like being buried alive.”

Touchè Caman, U.S. deportee and organizer for Chans Altenativ

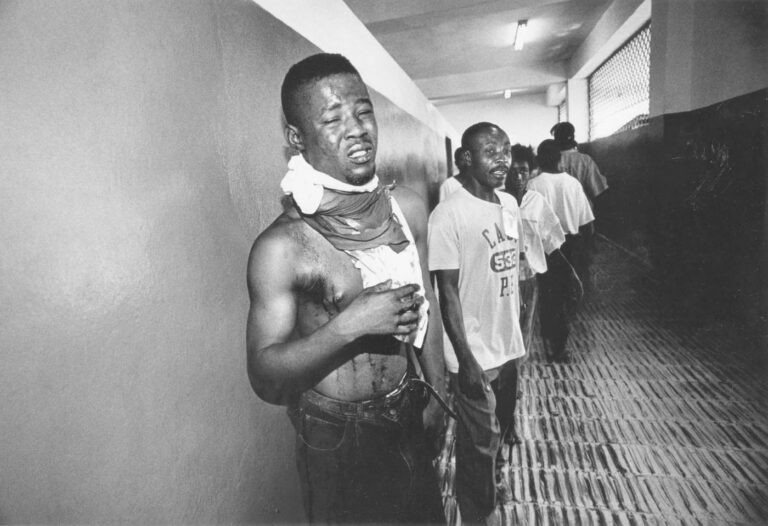

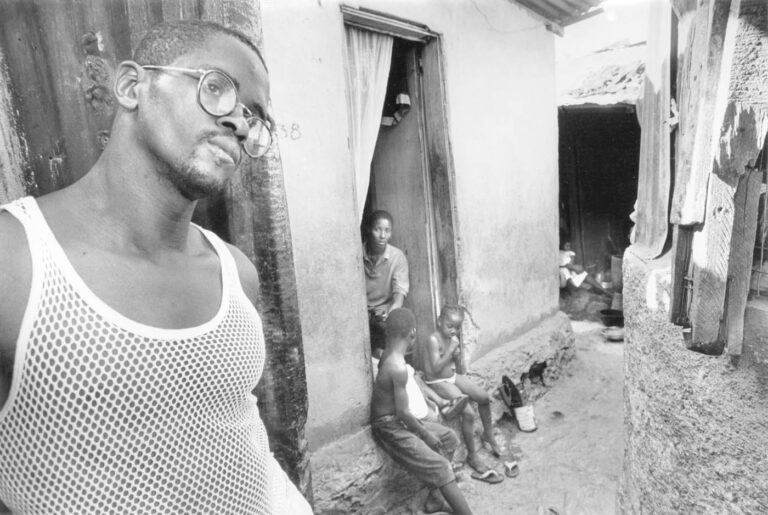

Port-au-Prince, Haiti—On the second day of his homecoming—after living eleven years in the United States—twenty-two-year old Patrick Etienne is overcome with emotion. The silent rivulets streaking his cheeks and staining his pristine white tee shirt are not tears of joy.

Along with 36 other criminal deportees, he was escorted by U.S. Federal Marshals onto a special plane and released into the hands of CIMO, the paramilitary anti-riot squad of the Haitian National Police. Patrick doesn’t yell—as several of his cell mates do—about his rights or the unsanitary and primitive toilet facilities here at the Haitian National Penitentiary where the group are being held. “Just wait till they get outside,” he utters in a barely audible whisper

As Patrick describes the incident that has landed him back in Haiti—injury he caused another motorist when, without a driver’s license, he took his mother’s car for a spin—anguish is visible in his young eyes. He doesn’t know if he will see his parents and siblings or the modest comforts of their Miami home again. Patrick recalls from childhood memory the destitution in which his extended family live—nearly a day’s journey over the crater-pocked road to Cap Haitien.

Patrick is embarrassed about the shame he will likely cause his relatives: US deportees are regarded as vile thugs in Haiti. “I have a sense of morality,” he tells me defensively. Struggling to keep his dignity as he wipes his eyes, he continues imploringly, “I just hope I can find work and that others can learn from my experience.”

In a country where fewer than half of all adults are literate, Patrick’s credentials—a year of community college, fluent English and fluent Spanish—are impressive. Yet they will be of marginal use without French, the language of Haiti’s educated elite. His chances of getting a job of any kind are a long shot in a land with nearly 80% unemployment.

Patrick’s fate is part of a recent trend. Every year the United States deports thousands of foreign-born youths with U.S. criminal convictions to Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. Few among them are drug kingpins or sophisticates from the ranks of organized crime. Most have already completed U.S. prison sentences when the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) scoops them up and sends them “home.”

U.S. frustration with crime and illegal immigration have changed the rules for non-citizens. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 and anti-terrorism legislation passed that same year now mean that one brush with the law, one strike, may put you out of the country. The INS deported 254 criminals to Haiti in 1997. The figures for the first half of 1998 were roughly 35% higher and other Caribbean and Central American countries are all seeing increases.

In U.S. ghettos, where struggling immigrant families live alongside America’s jobless, public institutions are being eroded by funding cuts. Overworked judges and lawyers routinely process cases with plea bargains rather than the clearer, but slower and more costly determination of guilt or innocence afforded by jury trial. Public defenders, unaware of their clients’ immigration status, unwittingly advise them to accept more lenient plea sentencing when doing so leaves any non-citizen, even permanent legal residents, vulnerable to deportation. Many Haitian criminal deportees have plea-bargain convictions. Most often they are for non-violent street level drug offenses.

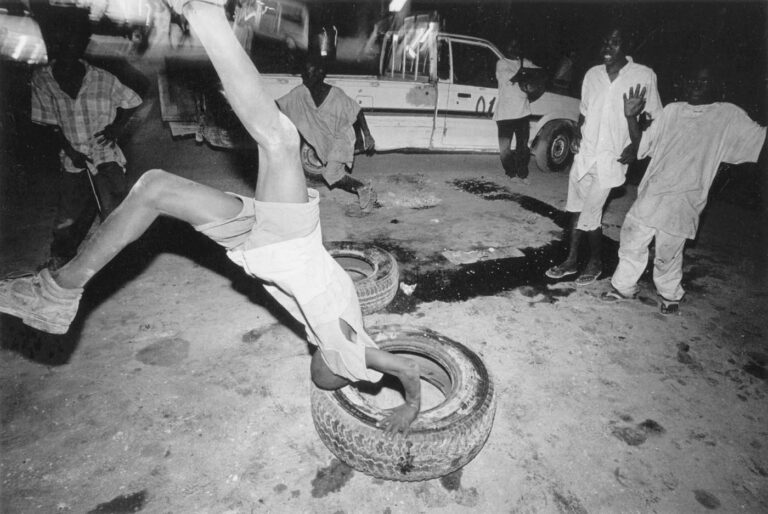

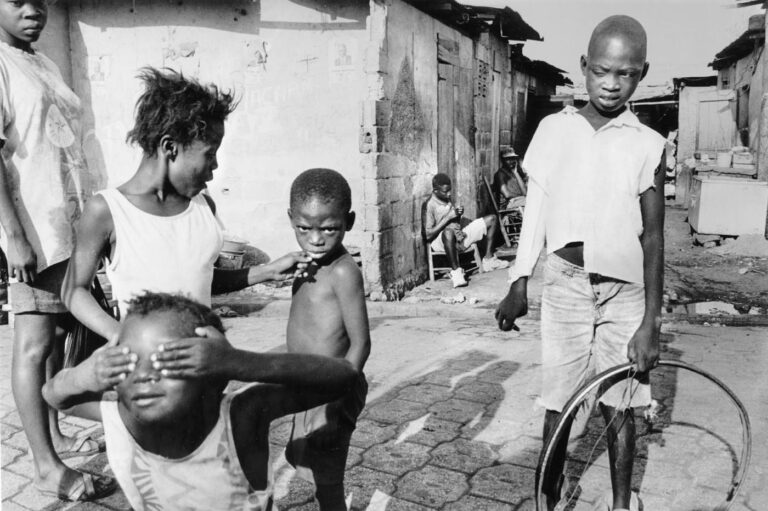

Crime and punishment are big concerns not only in the United States, but throughout Central America and the Caribbean. The emergence of youth gangs beyond U.S. borders and rising rates of violent crime, in countries as culturally distinct as El Salvador and Haiti, are routinely attributed to the burgeoning numbers of U.S. criminal deportees and gang members who arrive in the region each year. Frustrated with corrupt and inefficient judicial systems, citizens are often willing to accept vigilantism in response to crime and juvenile delinquency.

Elizè, a broad-shouldered Haitian youth, weaves through sweating crowds dodging the reckless and colorful public transports known as tap taps to lead me into a crumbling building. Dank air provides relief from the tropical heat outside. The winding passage offers a visual tour of poverty and technology from different centuries. I am reminded of Cairo’s subterranean catacombs where Egypt’s contemporary poor live side by side with the dead. But nothing here resembles even shabby Egyptian grandeur. These are private scenes of misery and degradation made public through gaping holes in the walls

Reaching the end of the passage we climb through one of the larger holes to a cell-like enclosure. The man I am seeking—a deported member of Miami’s Zo Pound gang—eludes me still. The room is empty but for rubble and a white Princess Line Touch Tone phone.

“Maybe he come later,” Elizè’s Creole cadenced English replies to my questioning gaze. Seeing my disappointment he offers, “You call States—50 gourdes 5 minute.” He offers me the Haitian rate three U.S. dollars. It’s half the rate he normally charges blancs—as whites, the wealthy or foreigners are known—and a third the price charged by the state-run monopoly Telecor. I make a collect call—not wanting to insult Elizè’s gesture of friendship or add to the bill of the person whose line this phone illegally tampers.

Elizè smiles knowingly at my misgivings about his fraudulent phone. A sense of security, a bourgeois belief that hard work results in progress, or deeply held ethical convictions are necessary to have such scruples. Elizè is not without values. He resisted the corrupt and cruel Duvalier regime. For Elizè’s generation the spiritually-based democracy movement, of the radical former-priest Jean Bertrand Aristede, was hope’s most potent symbol.

Now like many other Haitians his age, he faces the transition to democracy at the end of the millennium with anxiety over violent crime exacerbating perpetual third world miseries. The euphoria and terror of recent Haitian history—from the ousting of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986 through the long and violent backlash against those struggling for democratic rule—has worn people out.

The murder rate for young men remains high, but in the late 90s the body count is seldom politically motivated. Homicide is most often the work of vigilantes, angry mobs or criminal gangs. Persistent corruption and economic recession have eroded faith in political leaders. In the cosmos Elizè currently inhabits, virtue is either a mirage or a luxury he can ill afford. He is not cold-hearted. But the only effort that strikes him as genuine or vital is amorally Darwinian—the struggle to live.

In another part of the city I find Elizè’s friend—the brains behind the phone tampering scheme and one of several Zo Pound gang members from Miami that I’ve learned are living in Port-au-Prince. According to Ronald (not his real name) Zo Pound doesn’t operate as a gang in Haiti. “I don’t really know who’s really my friend anymore,” he tells me adding that “in Haiti it’s every man for himself.”

Ronald says most criminal deportees he knows survive on money sent by their families in the States, or hang around the airport and hotels hoping either to wash cars for tourists and visiting Diaspora Haitians or find day work as English-speaking guides. Some sell marijuana. Others get involved in more nefarious petty schemes like loan sharking—common in slums where few people have access to credit through banks.

One criminal deportee I met boasted earning $200 U.S. dollars a day from an American TV network for translation services during the deployment of 23,000 U.S. troops accompanying exiled President Aristede on his return. It’s an awesome sum when one considers that the per capita Gross National Product of Haiti is $230 U.S. dollars a year

Several gold-toothed deportees, hawking goods at an industrial park, reminisced about profiteering from U.S. servicemen they provided with art, drugs and prostitutes. When I asked Ronald about their stories he shrugged. “Myself, I catch wires for clients who want a long distance line. It’s not legit. But even the police show up at the spot to call the States.”

Though police spokesmen, Haitian officials and the press blame increased violent crime on U.S. criminal deportees, Ronald feels they’re simply scapegoats. “There’s a few deportees committing crimes, but they working for bigger crooks. Trust me if they didn’t have somebody to back em up, they wouldn’t do it. Somebody that knows this country good like the palm of their hands, that got access, that got guns. Cause believe me man, the moment that you step out that airplane you know you in a different world. You see bodies every week, all these young guys waking up dead. They from this country. There is no law, you know. Kill or be killed. It’s a jungle for real. If you want to live civilized, you got to have money.”

The police station in Cite Soleil is the Fort Apache of Port-au-Prince. Police Inspector Bazille Berthony never gives his schedule to anyone and he varies the route by which he enters the Cite. He has been threatened with grenades and his car tires have been shot up on more than one occasion. According to Berthony, it isn’t U.S. deportees who are leading the gangs here.

“Base Big Up, our largest gang, existed when I was a child growing up here in the Cite,” the 23-year-old inspector tells me. He adds that the leaders of Haiti’s most notorious gangs include corrupt cops drummed out of the newly formed Haitian National Police and former Ton Ton Macoutes as well as members of criminal families. “During the confusion of the post-Duvalier era, criminal gangs began recruiting twelve and thirteen year-old youngsters from the slums. We are now in our third generation of these gangs,” Berthony sighs. “They are a minority, but they are well armed and they terrorize the populace.”

Many local officials and some U.S. military personnel I spoke with claimed U.S. deportees were behind the Haitian gangs. But a foreign police trainer whose expertise in organized crime includes training and investigative operations in Mexico and Lebanon, confirmed Inspector Berthony’s assessment. “There is neither the critical mass in terms of numbers of U.S. criminal deportees nor the organized gang structures among them to have the kind of significant impact on crime that U.S. gangs are beginning to have in Mexico,” he told me. He also confirmed that some of the police who have been dismissed from the Haitian National Police force are now involved in criminal gangs. He says the most significant law enforcement problem Haiti faces is corrupt magistrates who, for a price, grant criminals impunity.

In this context, any effort to fight despair and restore faith is both admirable and inspiring. Michelle Karshan, an American supporter of Haiti’s democracy movement, has chosen to focus her efforts on building a sense of community and hope among one of the country’s most despised and feared groups—U.S. criminal deportees. She knows many Haitians are baffled about why she wants to help outlaws, who blew their chances in the land of opportunity, when there are so many innocent starving children in Haiti. But Karshan believes these “Americanized” Haitians have skills Haiti needs. She says that the social cost of ignoring them will eventually be increased crime and that Haiti can offer these prodigal sons a sense of identity and a purpose beyond the alienating materialism of the street life most knew in the U.S.

“Many of these young men are very bright, with strong English skills and more formal education than most Haitians, but criminal deportees fall into a caste system,” Karshan explains. “When these guys first get here they feel they’ve been banished” she adds, explaining that they are caught between two worlds. “They are traumatized by so much misery. How do you cope with Haiti when you grew up on U.S. television sit coms?”

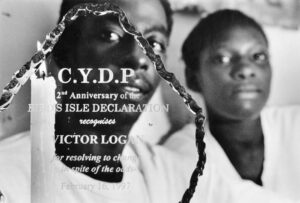

With Karshan’s help, a handful of criminal deportees formed a support group in early 1996. In Creole it is called Chans Altenativ (Alternative Chance). The program offers deportees, most of whom are coming straight from U.S. jails or INS detention, a fresh start and a bridge to understanding Haiti. Since its inception, Chans Altenativ has offered classes in Creole and French, computer skills, non-violence training, and life skills. It has helped some members with referrals to alcohol and substance abuse support groups as well as clinic referrals for health and nutrition problems. For those without relatives in Haiti, Chans Altenativ is the closest thing to family.

Sheltering from the morning downpour, I stop at the home of Touchè Caman, an organizer and founding member of Chans Altenativ. The fetid grey sludge that on drier days creates mucky lanes throughout the La Saline slum, swells into a knee-high filthy river outside the cramped quarters where Caman, his girlfriend and their two children huddle. “If you think this is bad,” Caman shouts above the metallic din of raindrops pelting his leaky roof, “just wait till I take you to see the sewage flowing through Cite Soleil. “You’ll see why they say it takes a germ the size of an elephant to kill a Haitian,” he tells me laughing.

Caman, a 28-year-old street tough who left Haiti at age five and grew up in Stamford Connecticut, is one of my guides through the nether world of Port-au-Prince slums. He spent 3 1/2 years in U.S. prison for trafficking in drugs before being deported to Haiti five years ago. He alternates between hip sardonic banter and glib efforts to shock me with P.T. Barnum visions of the bizarre. But behind all his defensive theatricality, Caman’s African “American” eyes offer a complex and poignant vision of Haiti and of his immigrant childhood.

“I grew up around second generation Irish and Italians. I thought I was as American as them.” Caman tells me. “At our family gatherings or weddings just like theirs there’d be tons of food. But then you’d see a Haitian take a whole tray of rice. You’d think to yourself who takes rice, a whole platter? It was always look at them Haitians. They seemed like unkempt children. I didn’t feel Haitian,” he says shaking his head before adding: “You don’t know what hungry means till you’ve seen people starving like they do in the provinces here. Now I understand about the plates of rice.”

Understanding and laying to rest wounded feelings is something his work with other deported youths is helping him achieve. “I’ll never forget the day my father made me wear my older sister’s hand-me-down jeans to school,” Caman tells me raw emotion in his voice. The fact that he was twelve and that the jeans were obviously girls’ is but one example of a kind of deprivation and humiliation not easily understood by elders formed in a country where children wear rags.

His father’s own deprived background and stern rigidity made him unable to sympathize with a son’s embarrassment. The conflicts that resulted between father and son led Caman to leave home at 15. An avid reader, he completed high school. But to survive, Caman began living a street hustler’s life and that eventually landed him back in his father’s country.

Being sent to Haiti—the poorest, most deprived corner of the Western Hemisphere—after having paid for whatever crime landed you in prison is a harsher fate than most deportees face. “It’s a life sentence, like being sent to die in Hell,” Caman remarks. “I used to see Haiti on TV and change the channel— all that poverty and violence. Who wants to go to Haiti? You want to go to Hawaii.”

Caman spent his first years in Haiti deeply depressed. He missed his family and his American-born daughter. He spoke no French and little Creole. Haiti was shocking. “Nobody ever told me about this stuff, child slavery, kids with huge bellies and diseases we have vaccines for,” he tells me his eyes widening. “You just can’t believe people can live like this. It’s not human.”

Everywhere he looked, Caman saw corruption and degradation. It was hard for him to feel pride in anything. “They told me this is a black country, “ he says shaking his head. Observing the mulatto caste system based on skin color and the power of U.S. dollars, Caman concluded: “The only two colors that matter here are white and green.”

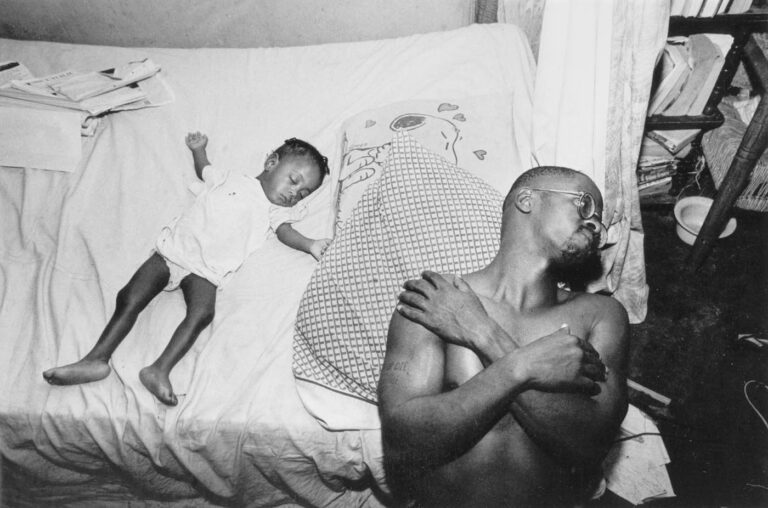

After his first year, Caman settled down with his girlfriend Alud and their son, Malcolm, was born. By the time of his daughter Jasmine’s premature birth, Caman’s economic situation had worsened and Alud was in poor health. The baby was tiny as most preemies are. Though she grew, she failed to crawl. Caman and Alud waited hours at clinic after clinic only to be told that the child’s condition was likely congenital. It was the lowest point in his life.

These days, Caman is guardedly optimistic about the future. A doctor he met through friends of Chans Altenativ diagnosed his daughter with rickets. Since beginning her vitamin treatments and physical therapy Jasmine is beginning to walk. “I wasted so much time before I got on track with Chans Altenativ,” Caman says.

The members of Chans Altenativ have ideas for expansion. The group have recently acquired a new location that will be their own and they have plans to open a restaurant—a venture that will help members by creating employment and raising funds for the program. A weekly hour-long radio show hosted by Chans Altenativ members also is being launched. It will increase the group’s outreach and discuss issues of interest to young people.

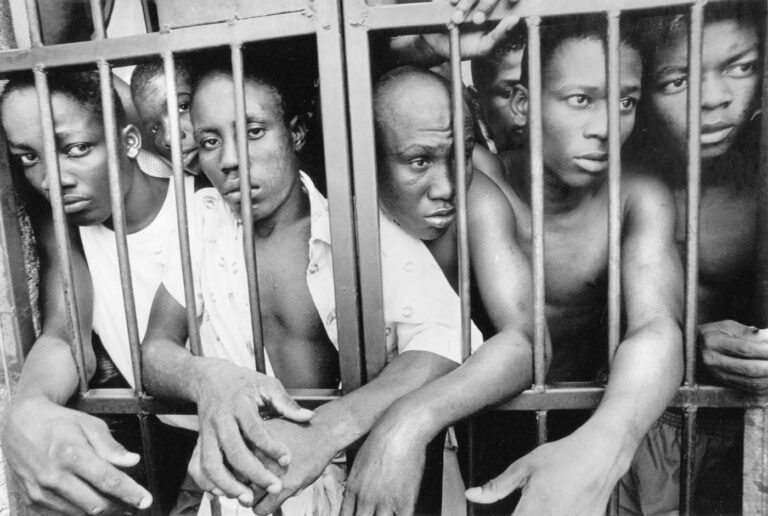

![At the Haitian National Penitentiary, Touchè Caman does outreach for Chans Altenativ. looking for deportees among the inmates. “I never thought I’d be going back into a prison after the last time,” he tells me laughing. “It’s a lot different on the other side [of the bars]. “Maybe Chans Altenativ can help a few of them when they get out.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DeCesare_Haiti01-768x522.jpg)

“At least we can help others understand where they are, learn from our mistakes and know they are not alone.” Caman says. That is perhaps the most potent hope that Michelle Karshan, Caman, and the other members of Chans Altenativ hold out to newly arriving deportees like Patrick Etienne.

©2000 Donna DeCesare

Donna DeCesare, a freelance photographer in New York City, is researching and illustrating youth identity and gang violence in the Americas.

![At the Haitian National Penitentiary, Touchè Caman does outreach for Chans Altenativ. looking for deportees among the inmates. “I never thought I’d be going back into a prison after the last time,” he tells me laughing. “It’s a lot different on the other side [of the bars]. “Maybe Chans Altenativ can help a few of them when they get out.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DeCesare_Haiti01-300x204.jpg)