Built along the Nile in Southern Egypt, the town of Luxor is near the ancient city of Thebes, which served as the capital of Egypt during the period known as The New Kingdom (1,539-1070 BC). In just a few square miles, it contains what is perhaps the greatest concentration of pharaonic monuments in Egypt: the glorious temples of Luxor and Karnak on one side of the river and the vast Theban necropolis on the other, containing the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens and the Valley of the Nobles, where Egyptian royalty of the New Kingdom from King Tutankhamen to Queen Nefertari have their tombs.

Outside of the tourist area, life in Luxor is still largely rural and moves to the rhythms of life that were established in Egypt about six or seven thousand years ago when Nile Valley civilization began. You can see men following a horse and plow across a field, women carrying huge bundles of sticks on their heads and children driving a donkey cart. The ancient Egyptians believed that the cycle of life and death was repeated every day by the sun’s course as it rose over the temples of Luxor and Karnak, proceeded slowly across the river and set over the craggy hills of the Theban necropolis on the West Bank. Virtually all royal tombs and pyramids in ancient Egypt were placed on the West Bank of the Nile, where they believed the kingdom of the dead resided.

The two ancient temples used to form the markers of the two ends of town, with Luxor at the south and Karnak on the northern edge of town, but in the last twenty years, the town has grown, the Eastern bank is lined with luxury five-star hotels and now Sheraton Hotel constitutes the southern edge of Luxor, while the Hilton hotel a mile or so past Karnak forms the northern border. Until recently, the only way to cross over to the Theban necropolis was by ferry, a long slow, twenty-minute ride amidst the chickens and goats of Egyptian farmers wearing turbans and galabayas (robes). The river was about the only thing slowing down the juggernaut of international tourism streaming across the see the tombs of the West Bank. But the Egyptians are now opening a bridge across the Nile so that the giant air-conditioned tour buses can drive straight up to the entrance of the necropolis.

Three million tourists visited Egypt last year, spending a record three billion dollars, making tourism the nation’s biggest growth industry. The minister of tourism says he expects these numbers to double by the end of the century. With Egypt’s population expected to rise from 64 million to 100 million in the next fifty years, the government is counting on a growing tourist industry to meet the country’s rapidly expanding needs.

The Egyptian government is aware that it needs to protect the monuments if it wants to keep its tourist economy healthy, but doing so often conflicts with other needs and interests.

In the Valley of the Nobles – the smallest of the three main burial sites at Thebes – there is an entire village living literally on top of the underground tombs. The sewage from the houses drain off into the tomb areas, adding to the problem of salt crystallization. When the walls of the tombs become wet, salt inside the surface moves to the surface attracted by the moisture. When the walls dry, the salt crystallizes and hardens, expanding in size and pushing out the surface of the wall, which begins to peel off. The government has tried to get local residents to move out and has even built new housing for them elsewhere. But they do not want to move because they are living on top of their livelihood in a major tourist site where they can sell soft drinks or souvenirs to tourists out of their own homes. In a country where the average person makes about two dollars a day, they are living in the middle of a major income stream.

“There are many different interests we have to keep in mind and try to reconcile,” says Faiza Haikel, a noted Egyptian archaeologist who is heading up Egypt’s Sinai Salvage Project, an effort to identify and secure archaeological sites in the Sinai before the area is entirely developed as a resort for tourists wanting to vacation along the Red Sea.

“If you go to speak to the local people who live near and on top of the monuments, they think the monuments belong to them,” Haikel explains. “They believe that they are free to do with them what they want, to chip paintings off the wall, to dig up objects and melt them down. Then you have the Egyptian government that sees them as a national resource and as a great economic resource through tourism and finally you have the foreign archaeologists and the Egyptian scholars who see them as world heritage that belong to everyone and are to be preserved for the future.”

Luxor is in many ways a perfect place from which to observe these different interests at work and often in conflict.

Modern Egypt is struggling with problems of truly gargantuan proportions: Although a country with a vast territory larger than the states of Texas and New Mexico combined, 96 percent of the land is desert, forcing virtually the entire population to live and work on the thin green ribbon of arable land on either side of the Nile River that flows from its border with Sudan on the south to the Mediterranean. At the height of its glory, ancient Egypt is believed to have supported a population of between one and two million on the same territory where 64 million now live.

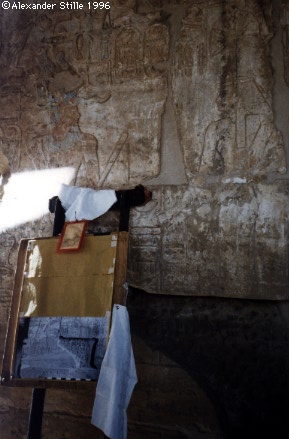

Modern Egypt – needing to feed its exploding population is furiously trying to make more of its land available for agriculture to feed and house its people through year-round irrigation. The water table of the entire country has risen a full meter in just forty years and monuments that once stood in dry sand are bathed in water throughout the year. Glorious temple columns of limestone and sandstone are gradually crumbling back into sand. The deadly white bloom of salt crystallization can be seen on the temple walls at Luxor eating away delicately-carved inscriptions and sculptural reliefs that have captured the triumphs, joys, incantations and fears of a long-past civilization.

“We are trying to document as much as we can before it disappears,” says Peter Dorman, the director of Chicago House, the University of Chicago’s residence in Luxor. The scholars from Chicago have been concentrating their energies on accurately transcribing the reliefs at Luxor and an equally important temple in the necropolis area. But fully documenting a major temple – painstakingly photographing, drawing, and transcribing faded and sometimes fragmentary scenes and inscriptions – can take twenty years. Photographs made earlier in this century show clearly that many scenes and inscriptions are already gone – most of the damage having occurred in the last generation.

“When the temples of southern Egypt were flooded by the building of the high dam at Aswan, the whole world mobilized to save them because the problem was so dramatic and obvious to people,” says Professor Ray Johnson, a member of the University of Chicago team at Luxor, “but the current problem is just as serious, but in some ways even more insidious because it’s so subtle and gradual that the casual observer would hardly notice. If you go to the temples of Karnak and Luxor, you see these huge columns and pylons still standing and you say, ‘Gee, they look pretty good to me,’ but if you look more closely, you realize that it could all collapse.”

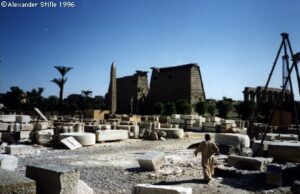

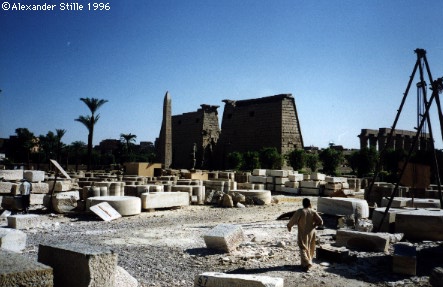

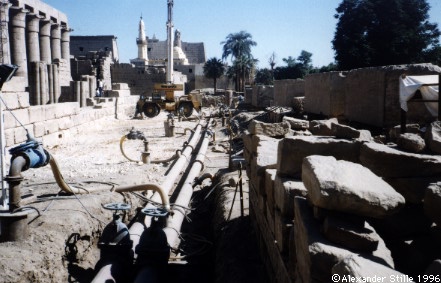

The Egyptians have had to remove an entire row of columns from the Luxor Temple because of stability problems. Twenty years ago, Professor Johnson was standing on a scaffolding near the columns when an earthquake erupted. “The columns swayed, because the ancient Egyptian built them in sections so that they would be flexible, but they didn’t budge,” he recalls. “Now that it is the last place I would want to be during an earthquake.” Currently, Egyptian workmen are laying new foundations for the columns and a pump is working sucking up water near the temple trying to lower the water table. But engineers warn that the pumping may potentially make the problem worse. When you pump water from the ground, if you pump too vigorously, you bring up fine particles from the underlying soil. The ground shifts to compensate for the missing particles that are sucked up with the water, destabilizing the walls and foundations of buildings. On the north end of the temple site, Egyptian workmen are busy carving sandstone. They are actually replacing entire sections of the 3,000-year old columns with newly-carved stone.

At the Valley of the Kings on the West Bank, thousands of tourists arrive each day, crowding sometimes ten or twenty at a time into small tombs that were built never to be entered by anyone. Carved deep underground in order to hide their treasures, the tombs are small enclosed spaces, that can become incredibly hot and humid when filled with people.

Conditions in the tomb of Queen Nefertari, the favorite wife of Ramses the Great, had deteriorated so badly that it remained closed for nearly twenty years, with much of its paint flaking and held on with gauze strips that look like bandages. During the 1980’s, the Getty Conservation Institute in California undertook a major restoration that restored the tomb to the best condition it has been in since its discovery in 1904. In the course of the restoration, Getty scientists conducted a series of careful tests that measured the effect of visitors on the environment of the tomb. They found that the presence of even a small number of visitors drastically altered the relative humidity of the tomb and that – especially in the hot summer months – it took the tomb several days to recover its equilibrium. The Getty also created a “virtual reality” reconstruction of the tomb in hopes of convincing the Egyptian government to keep the tomb closed to the general public and to use the three-dimensional computer-simulated version as a replacement.

The Egyptian antiquities service – badly in need of foreign currency – reopened Nefertari to tourists, and it is not hard to understand why. The cost of a ten-minute visit to the tomb is 100 Egyptian pounds (about $34 U.S. dollars) per person, which is the same as the monthly salary of a trained archeologist or a museum guard working for the Supreme Council of Egyptian Antiquities. The recently-restored tomb of Queen Nefertari in Luxor is more brilliantly-colored than its virtual reality version could possibly suggest, but its condition is extremely fragile. Nefertari looks like a beautiful patient on life support, with wires sprouting from every wall to various machines monitoring her every breath and heart beat. Despite the extremely high cost, as many as 150 tourists have been lining up each day to see the tomb, much to the distress of the Getty Conservation Institute. Only a few miles away in the Valley of the Kings is an example of what can happen: the equally splendid tomb of King Seti I has been closed after much of its painted ceiling simply fell in one day. Swiss archeologists are so worried about the problem that they have proposed closing all the tombs in the area and making replicas of them for tourists to visit.

“We have reached a point where push has come to shove,” says Kent Weeks, an Egyptologist with the American University of Cairo, who has worked in Luxor for more than thirty years and recently made the renowned discovery of the tombs of the sons of the Ramses the Great in the Valley of the Kings. “Because of the combined forces of population increase, urbanization, pollution, the rising water table and mass tourism, things have reached a critical threshold: if we don’t do something very soon, in another generation we are going to be faced with some very ugly choices: One third of the monuments may be gone, one third may be fine and we will have to concentrate our efforts on saving the remaining third.”

Although particularly acute in Egypt, the same pressures are at work throughout the world. “You could say the same thing about virtually any country with significant antiquities,” says British egyptologist Chris Ehre, of the University of Liverpool. “Italy will probably lose even more because it has too many monuments.”

©1997 Alexander Stille

Alexander Stille, a freelance writer in Atlanta, Georgia, is examining the future of the world’s past.