It’s hard to find a better potato farmer in Southwest France than Jose Sanchez. He started from scratch ten years ago on about five acres of land, tearing up cypress wind barriers and planting new ones, filling in gulches with cart loads of dirt to create the smooth fields he now works from dawn to midnight six and seven days a week during harvest time.

Today Sanchez (who like many farmers in this region that once belonged to Spain, has Spanish ancestors to account for his name) owns about 12 acres and rents an additional eight. He owns all kinds of machinery and employs one farmhand year round. If he unable to meet his $19,000 payment on a government loan this year it will be through no fault in his farming, but because like a good part of the farmers in the ten-member European Economic Community (EEC), he is far too successful for his own good. In this season of plenty, potatoes from Spain, Italy, Germany, and France are flooding the European market. Although it cost Sanchez about 16 cents to produce each kilo (2.2 pounds), potatoes are going for about one-third of that a kilo on the wholesale market. At age 32, Sanchez is contemplating the possibility of complete financial failure.

For twenty years, EEC farmers have reaped the benefits of a program designed to ensure that Europe would never again suffer the hunger that followed the devastation of World War II. The program, known as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), worked. Only ten years ago the agricultural sector was perhaps the proudest embodiment of the EEC’s project for a united, stable Europe. The ambitious goals of agricultural self-sufficiency, stable food prices and improved living conditions for farmers had been largely achieved.

Today however, the harvest of success is bitter. European farmers like Sanchez are producing too much food for the market, and prices are collapsing. Almost 70% of the EEC’s $22.1 billion annual budget goes to the CAP. And two-thirds of that goes to buying the surplus production of certain key products at guaranteed prices–notably milk, cereals and meat. But for the second year in a row, CAP funds have been insufficient to deal with the growing surpluses, and the program has had to rely on advance funds from the expected contributions of member nations. It is generally recognized that a radical restructuring of the EEC’s agricultural policies is urgent, but with unemployment stubbornly holding at around 12% across the community, cutbacks in subsidized agriculture could threaten social stability by forcing farmers off the land without providing an alternative. In France, where there are already far more unemployed (2.5 million) than members of the agricultural labor force (1.7 million) this is a particularly acute problem.

On the international horizon, even darker clouds are gathering: next year Portugal and Spain will join the EEC, adding their large stock of cheaply produced wine, fruits and vegetables to the common pool. And across the Atlantic, the United States is threatening to regain some of the international grain market lost to EEC competition.

Sanchez and his wife, Christiane, discovered how close they were to catastrophe on an early morning last June when they took their first crates of potatoes from the summer harvest to the local agricultural wholesale market in Perpignan. Unable to find a bidder who would pay anywhere near their break-even price, they took their produce out of auction. Later that day, standing in front of the magnificent but still unfinished house that Jose Sanchez has been building for the last four years, Christiane was almost beside herself with anguish. “We’ve had bad times before,” she said, “but never one bad season after another after another like this, that leaves us no chance to recover. What are we going to do? We couldn’t even sell the land to pay off our bills because nobody will buy (it) any more. Agriculture is simply no good.”

In late spring and early summer I talked with farmers in northern and southern France about the problems their success had brought. In the past northern French dairy farmers have benefited enormously from CAP programs designed first to stimulate production and then to deal with the surplus by purchasing it at guaranteed prices. In southern France farmers have enjoyed far less protection from the EEC’s Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund, but in both areas the fundamental problem remains the same. Productivity has increased beyond demand, but farmers must keep producing in order to keep up with the rising costs of machinery, seed, fertilizers and feed, and rising interest rates on government loans. In the process, the European Community’s Common Market, conceived as a unified force large enough to compete with the other major world economies at a time of world economic expansion, has become a common battleground where member states compete for a share of the market while facing growing competition from abroad.

Producers like Sanchez know that the number of farmers will diminish drastically in the next few years, and that those units which survive the shakedown will do so by producing food at much lower prices. But in northern Brittany, Georges Lemarchand, a successful dairy farmer, pointed out that it takes a lot of money to produce food cheaply. “We had to buy equipment,” he said, “a manure spreader, ensilage harvester, baler, forage condenser.” The machinery allows Lemarchand to keep up with the efficiency and productivity of northern European dairy farms, but it costs money. In order to keep up with his loan payments, Lemarchand must produce ever-increasing amounts of milk, if only to sell it to the French government, which under the EEC’s guarantee program pays a fixed price for the milk and processes it for storage. This absurd cycle has led to the EEC’s notorious “milk lakes” and “butter mountains.”

Like other European dairy farmers, Lemarchand is vehemently opposed to the 8.8% milk production quotas imposed last year by the EEC. Lemarchand says the smaller farmers can’t survive any reductions in their income and the statistics indicate he is right. Since the cutbacks were imposed a year ago last March, more than 10% of France’s 440,000 dairy farms have abandoned milk production altogether. According to Jacques Barret, spokesman for the powerful trade organization, the Assemblee Permanante des Chambres d’Agriculture, many of these farms have switched over to less capital intensive crops with a far lower cash yield, and their future remains uncertain. Dependence on the CAP’s surplus purchase program has become the only guarantee of economic survival for many farmers, but it is also a barrier to agricultural innovation and successful adaptation to the changing times.

A stench so powerful it could rival that of the most Herculean stable permeates the area around the Distillerie Cooperative of Cuxac, in the Languedoc region of the French Midi. Inside the cooperative, however, all is in order and cleanliness. Its main business is transforming locally produced wine into industrial-grade alcohol. The clear antiseptic liquid is stored inside in vats. Outside, a purple stream of wine by-products is responsible for the smell.

The distillery’s business is the result of a three-year old Community policy to keep wine prices from collapsing by removing a certain amount from the market each year. The policy affects ordinary wine–vin de tableand vin du pays–and not quality wine, which by definition is produced in limited amounts. As of this year small producers are required to distill about 2% of their yearly output. Larger growers must bring in at least 11.5% of their wine for distillation.

Jean Claude Cibenel, whose job it is to supervise this process in Cuxac, is highly critical of the policy, and it takes only a few minutes to understand why: “This year the hectoliter of alcohol is being paid at 236.6 francs,” he explained. “On the open market, the wine brings in about 165 francs. Many producers who don’t have enough wine to qualify for distillation are smuggling more in from Italy to make up their deficit. The policy simply does not encourage quality production.”

The last point is pertinent, because there is general agreement that one answer to surpluses–in wines as in every other product–is diversification, with a strong emphasis on quality production. Daniel Dulout, of the local Chamber of Agriculture, is a fervent advocate of quality vineyards, but it is difficult, he said to convince fellow wine-growers.

Dulout and I were headed for the village of Cucugnan (pop. 100), which sits on a hillside in view of the Chateau de Queribus, a medieval castle pitched on a blade of rocky mountain. Around us were the precipitous chalky slopes of the Languedoc garrigue, scented by lavender, punctuated here and there by parcels carved out of the hillside where Carignan grapes were preparing for their future as Corbieres (a ‘Vin d’Appellation d’Origine,’ or quality wine).

“At the Chamber we’re trying to associate our wines with ancient caves in the area,” Dulout said, “so that growers can profit from tourism by taking in paying guests. They cannot compete in the market on the basis of their quality wine alone. Take my case; it cost me about 220 francs to produce each hectoliter this year, and I will be getting about 238 francs for it. I do it for love.”

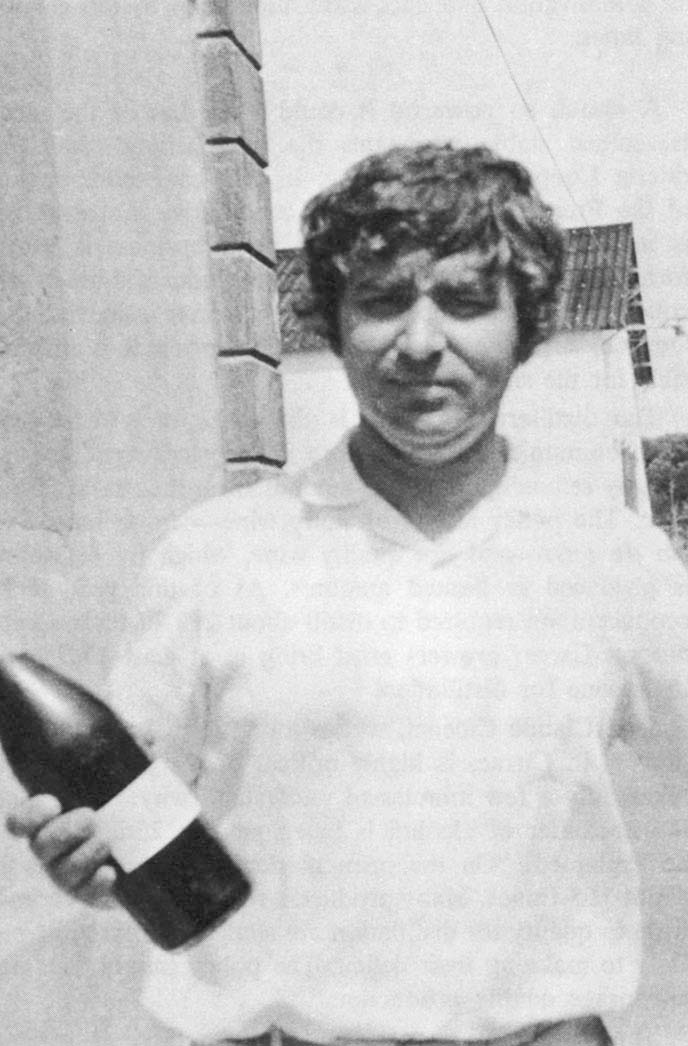

In Cucugnan, Michael Riviere, 32, with a wife and child to support, cannot afford to be so cavalier. Rather, he wonders if one if his neighbors hasn’t been more foresightful than he in selling off his land to set up a coffee shop, in expectation of tourists who have yet to arrive. Riviere owns about 25 acres and cannot hope to produce enough wine to qualify for the distillation quota. “So I hire myself out right and left to work in other growers’ vineyards. I’m always scrabbling for a solution. The Chamber recommends quality production, and I’d be willing to try, but it takes money.”

Because of unemployment, Riviere’s options would be drastically limited if he left his lovely village. And Dulout explained why Riviere cannot take advantage of a Community premium paid to growers who are willing to plough under their vineyards: “Can you tell me what other crop could produce a similar income per hectare on this dry, chalky, steep land?”

France’s farmers and politicians are coming to grips with the inevitable conclusion that a drastic reduction in the size of the agricultural labor force is in order. Many of the country’s 900,000 farms will have to go. “We estimate that fifteen years from now there will be 400 to 500 thousand economically viable exploitations (farms),” said the Chambres d’Agriculture’s Barret. “But the size of the agricultural sector will be the result of a political decision: if the government wants the cities full of the unemployed, then the number of farms will be limited to the profitable ones. But if the state desires to maintain some sort of social balance, it will have to provide assistance to a considerable portion of the current rural sector.”

Either alternative is politically fraught in an era of economic recession. Predictably, the crunch will hurt most those sectors of rural Europe which by general acknowledgment have benefited least from the CAP: the poor Mediterranean regions most dependent on agriculture, and the smaller farmers–the ones who with limited capital and knowledge force a precarious living from the land.

Henri Gispert bounded out from among his peach trees, barefoot and joyous. “Bon jour!” he virtually shouted at a visitor, stopping on the way to pick up a peach from a wheelbarrow and offer it with a handshake and a huge-toothed grin. “Ca va?” It was not the attitude one would expect at 8 o’clock in the morning from a 51year old man contemplating bankruptcy.

There was little time left for contemplation, in any event. In the orchard behind him four women–his wife, sister-in-law and two friends–were keeping up a conversation that flew as fast their hands. Testing a peach here, picking a peach there, rejecting a third, they filled their plastic crates as quickly as the burly Gispert could trundle them on his wheelbarrow and stack them on the back of a decrepit slatbed truck. It was the early harvest season and the picking on Gispert’s seven acres had to keep up with the fruit’s increasingly fast maturation.

But the market was no good. “This year I am making zero!” Gispert said with emphasis, describing an empty circle with one hand. “Wiped out!” His hand scythed down to the ground. “No profits for the last three years!” Both hands erased the future. He picked up his wheelbarrow again and trundled towards the truck. “Ten years ago peaches sold very well, and since everything else was doing very badly everybody began making peaches. Now it is the catastrophe. Agriculture is terrible everywhere, and it’s because there’s too much production, I believe.”

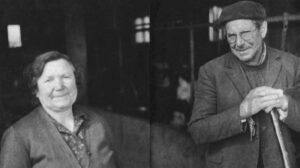

But how could Gispert not take pride in what he has built so painfully? He has been farming his land for 20 years. “Before that I had a second-hand tractor and I worked the fields for others,” he says. “Now I have this and the house…you will see.”

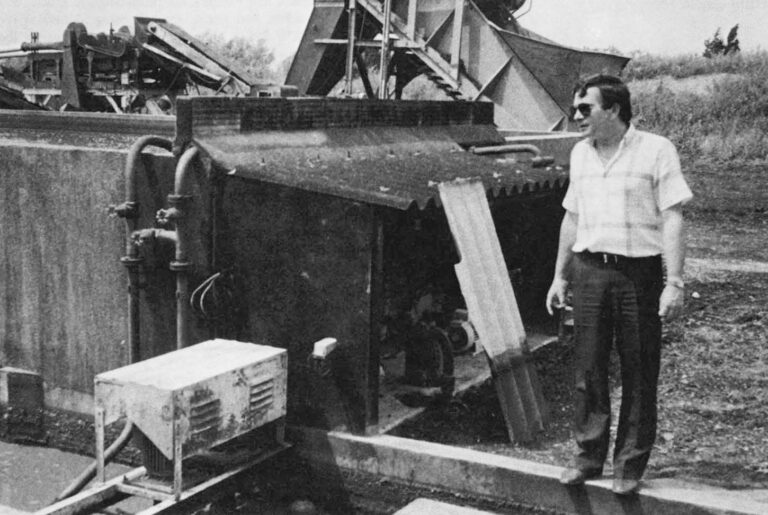

The small white house was drowning in a sea of roses and hortensias. Gispert’s mother-in-law dozed on the porch in the company of a marmalade cat. Her exemplary potato ragout wafted its scent into the garden, where the historic tractor sat along with Gispert’s most recent pride, a small mechanical fruit calibrator/sorter. “It’s good, no?” Gispert affirmed. It is indeed, but it doesn’t add up to a profit margin, “How could I ask my daughter to take this up?” he asked. “You know, the government talks about the SMIC (Salaire Minimum Interprofessionelle de Croissance, or minimum wage), but I don’t even make half the SMIC. I am up at dawn, I work until nightfall and after, but this year we are eating off our profits from the past.”

The future looks worse, because just across the border in Spain Gispert’s fellow Catalans are preparing what all of Southwest France describes as an invasion. With Spain’s formal entry into the European Economic Community due January 1, southern French growers will lose a vital seasonal advantage: The spring sun reaches Spain a few critical weeks earlier, and shines on a land where labor costs are about half as high as in France. “C’est la guerre,” Gispert says firmly. Again, the Common Market will be a common battleground.

The first skirmishes of the “war” are already being fought; Southern farmers have embarked on their seasonal ritual of emptying trucks bearing Spanish produce, and when President Francois Mitterand visited the region in late June, security forces had to step in to keep angry demonstrators from getting out of hand.

The protests are not expected to change much. A former high official in the Ministry of Agriculture pointed out that there are limited resources to cushion the blow of redundancy for small farmers. Two factors will reduce their number, he said: retirement among the. large proportion of farmers now over 50 years old, and the de facto dismantling of the CAP’s price support program. “Liberalized price policies will reduce the size of the (agricultural) sector,” he said. “As they have in the United States.”

“And where will we go?” asked Gispert. “Anguish is something that is strangling us all around here. The future is frightening. It belongs to the super-exploitations…” he searched for the word “…performantes. The small farmers will crack,” his hands described the breaking of twigs, “one after the other.” This absorbing thought brought Gispert to a halt in his trundling, but a few seconds later he was on his way again. “Of course I know what I will do,” he said. “I will sell everything and go hire myself out to one of those big exploitations, if they will have me.” He pointed towards the orchard and apologized to a visitor. “If you will excuse me now, I must go back to work.”

©1985 Alma Guillermoprieto

Alma Guillermoprieto, a reporter on leave from The Washington Post, is chronicling changes in rural life under the policies of the European Economic Community.