SANGUINEDO, Spain–Depending on how you look at it, Pepe Lopez came to farming by accident or by inescapable destiny. The accident was that he was caught without work papers and deported from Switzerland ten years ago. Destiny was waiting for him in the beautiful and backward region of Galicia, Spain, on the seven hectares of land his father, grandfather and great-grandfather had farmed before him, and which Lopez says he had wanted so much to escape.

Depending on how you look at it, Pepe Lopez, age 30, is a success or a failure. In Galicia, where poverty is as plentiful as potatoes, he is sitting right on the edge of prosperity, farming more land for pasture than his six neighbors own between them, and selling a major dairy company the milk from his 14 cows while his neighbors–like 70 percent of all Galician dairy farmers–each make do with six or fewer cows.

But on the production graphs of the European Economic Community (or Common Market, as it is also known), Lopez inhabits the gulches, far from the airy heights where Dutch and Danish farmers chart in with daily milk outputs of more than 18 liters per cow. When the milk company’s little Range Rover station wagon comes clattering down the road to his stable every day, Lopez’ father, Senor Jose, is pleased to be able to load it with a single 60-liter milk can, and he points to the clunky, hand-carried milking machine as the reason for the Lopez cows’ sudden surge in production two months ago, up from their previous hand-milked total of 45 liters or so a day.

The comparison with Common Market production figures is ominously relevant for Lopez and the estimated 250,000 other Galician dairy farmers who produce one-fourth of all the milk in Spain. Last March the EEC foreign ministers voted to admit Spain and Portugal as the 11th and 12th members of the Common Market, effective next year. At that time, the import barriers that currently protect Galicia from outside dairy competition will gradually be lifted, and the milk companies that buy and process milk in Galicia for sale in the rest of the country have made it clear that they will shift their purchases proportionately to the cheap high-quality milk that northern European farmers sell at below Lopez’ production costs.

Politicians across the broad Spanish spectrum agree that Common Market entry is an indispensable passport into the world of modern commerce, international politics and technology, but for Lopez the world is a smaller, more urgent place. “The Common Market…they say that’s coming to ruin us all, don’t they?” he said recently, his normally cheerful round face tight with worry. It was hard to know, either from his tone or his circumstances, whether the sentence was a question or a statement.

The Common Market is perhaps the single largest and most pervasive economic influence in rural Europe today. To a large degree, its Common Agricultural Policy determines what products some eight million people grow in the ten member countries, what price they receive for their products, how those products are processed and, increasingly, as agricultural production outstrips demand, how much of each product gets grown.

Since it was first formulated in 1962, the Common Agricultural Policy has contributed greatly to the vast improvement in living and working conditions in much of rural Europe. It has done so at huge financial cost, primarily by subsidizing guaranteed prices for many export and basic crops. But according to some of the EEC’s most thoughtful analysts, the policy has done little to diminish the stubborn gap between rich and poor member nations, between prosperous and backward regions in each country, and between those farmers who were already wealthy enough to adapt to EEC requirements and those who were ill-prepared to make the transition from a peasant subsistence economy to commercial farming.

It was in order to examine the possible impact of EEC policies on small farmers in rural Spain that I traveled last February to a tiny village in the parish (municipality) of Sanguinedo, Galicia, where the Lopez family lives. On the advice of the agricultural extension worker who provided my first contact with Sanguinedo, I stayed with the most prosperous family in the zone rather than the many much poorer ones. “For the poorer folk, it won’t make much difference whether we enter the EEC or not,” he said. “They are mostly over 50; most of them have pensions. They grow a little corn, a few potatoes, they’ll always be poor. It’s the people like Pepe, who have mortgaged their land in order to modernize, who live by the rules of the market, whose future is really at risk with entry.”

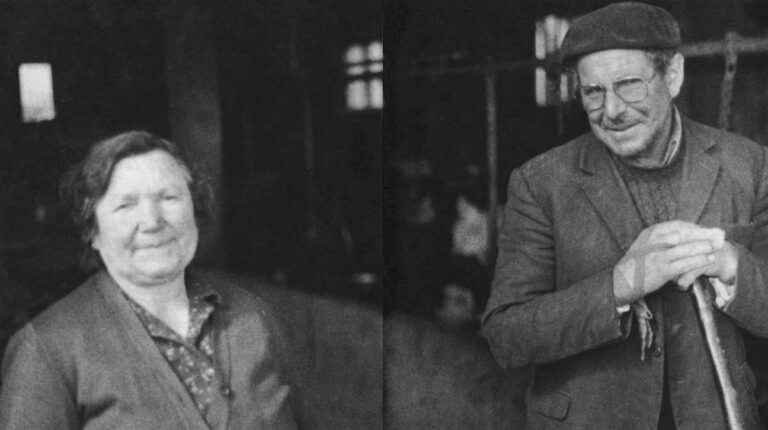

Everything about Pepe Lopez–the perfect Spanish he speaks, his brand-new two-story concrete house, the adjoining silo, his tractor, car, milking machine, the jaunty golf cap he sports–speaks of his one overwhelming longing: to be a part of the modern world.

Everything about his father speaks of tradition: Senor Jose wears the peasant’s dark suit and beret. Courtly, shy, spare of both flesh and word, he speaks only Galician, a blend of archaic Portuguese and modern Spanish. He never went to school, has never traveled further than the provincial capital–the breathtaking medieval city of Santiago de Compostela, some 70 kilometers away.

Every day, Senor Jose unlocks the cows from their stanchions in the stable on the ground floor of the Lopez home. Armed with galoshes and an umbrella against the persistent Galician rain, he escorts the herd out to pasture. Standing in the misty, hilly, green Galician landscape, he can look down the road or across the valley and see other peasants holding umbrellas and leading two or three cows on a leash or, like him, simply watching the animals to make sure they don’t trespass from one minute plot of land over to the neighbors’.

The younger Lopez has no time for these necessary but consuming tasks. He is always rushing somewhere: to the agricultural extension office to tend to the “young farmer” loan that enabled him to build the house, stable and silo two years ago, or to the local weekly town market, or to his tractor to etch a set of rows expertly into a plot ready for planting. These activities are part of the sharp distinction he draws between himself, his neighbors and–though he will not say it–his father: the others are “labradores”–tillers, or peasants. He is an “agricultor,” a farmer.

“Labradores don’t think ahead, only of getting by day to day,” he said, sipping coffee in the huge traditional kitchen/laundry/living room where the family always gathers for meals and for the warmth from the wood-burning stove that is kept burning almost permanently.

As we talked, his quiet and sensible wife, Clarita, knits a blanket for the baby she’s expecting in August, her first. Senor Jose listens, making no comment, but Pepe’s mother, Senora Manuela, is frequently the one to remember the precise year the tractor was purchased (1976), or explain the different advantages of Holstein and the native “rubia gallega” cows. She is by far the most lively and inquisitive member of the family, and at the same time the one most firmly rooted in tradition. After I had ruined four rolls of film trying to catch her mischievous smile, she explained in Galician why she put up her hand each time: “people would see me smiling all alone, without my husband, and they would think I am shameless.”

Now during this late evening conversation Senora Manuela is trying to press more food on me: “You can’t have children if you don’t have a good round belly to grow them in,” she says, as she does every time she ladles another boiled pig’s ear or more potatoes into my bowl at mealtimes. This time she’s trying to tempt me with home-cured ham. The family used to keep pigs and grow wheat, she says. Now there are chickens, small plots of cabbage, onions and beets, and a large field of potatoes, but under Pepe’s direction almost all the land and resources have been turned over to dairy farming. “In 1978 I decided that what we had to do was clear our idle land so we could accommodate more cattle in the future. I replaced our “rubia gallegas” [a native breed of cow, well-suited to plough-work but a dismal producer of milk] with Holstein-Freesians. Later I began to get friendly with the agricultural extension people and got a two-million peseta (about $20,000) loan to build this house. I look around me and see younger men who haven’t done what I have,” Lopez says.

What Lopez was doing at the time was responding adequately to a government policy encouraging milk production in Galicia. Both Madrid and the “Xunta,” or governing body of the autonomous region of Galicia, were interested in getting Lopez’ generation to stay on the land. Galicia’s traditional solution to land scarcity and poverty had always been emigration, but the deep European recession had cut off that route, as Lopez discovered in Switzerland. At the same time, milk consumption was rising rapidly throughout Spain. Galician farmers were encouraged to stay on the land and produce more. Lopez did so, and tied the first knot of the double-bind he is currently caught in:

On the one hand, Lopez’ cows produce scant quantities of milk at extremely high cost. On the other hand, if the Galician milk sector increases its efficiency, it will add to the stock available of a product the Common Market is currently drowning in. Milk is the single largest item in the Common Agricultural Policy’s subsidized purchases program. The Community bought and stockpiled almost $3 million worth of milk last year to keep the market from collapsing. Current Spanish government programs to modernize Galician agriculture run directly counter to Common Market policy discouraging dairy production, although it appears that under the terms of Spain’s entry, the programs will be allowed to continue during a seven-year transition period.

But have these programs–have the house and the stable and the silo and the second-hand milking machine–made it possible to make a decent living off the land? In unison, the younger and older couple shake their heads. “The monthly payments on the loan,” Senora Manuela says, “come out of our old-age pensions.” In Galicia, where thanks to emigration half the population is over 50, it is common and bitter knowledge that a young couple with a “crop of oldsters” (at least two surviving parents on pensions), is far more financially secure than a farmer with five cows.

The conversation has taken a somber turn. The normally irrepressible Senora Manuela is pensive. “Come, it’s almost midnight,” she says, shaking herself and touching her husband gently. “Let’s go do the milking.”

The stable at midnight is full of mysterious sounds: the milking machine’s motor roars outside, an industrial backdrop for the single cowbell ringing impatiently in the foreground; Paloma, one of the three “gallega” cows waiting for her calf to be brought to her. A dog whines, discomfited, as Senor Jose chases him from his bed of hay to grab an armful for Paloma. A hen squawks–”What time is it? What time is it?”–as it rustles awake. Senora Manuela milks Paloma by hand while the calf feeds, and Senor Jose attaches the rhythmically sloshing milking machine to one of the Holsteins. The stable at midnight, so idyllic, so Galician, is also a cemetery of good intentions, an inventory of planning mistakes, and a sort of monument to the difficulties of modernizing Galician dairy farming.

“You mean to tell me that this man got a two-million peseta loan and used it to build a house with a stanchion-type stable downstairs and no milking parlor?” Eloy Villada, one of the approximately 150 agricultural extension workers with the local Xunta, is incredulous. One after another, as he listens to my account, the factors emerge that are limiting Pepe Lopez’ production to a ruinous 60 or 70 liters a day. Lopez decided against the modern system of keeping cows outdoors except for feeding and milking, preferring to lock the cows in stanchions in a closed stable. “They would get cold otherwise,” he explains The Lopezes have not been taught to wash each cow’s udder down before milking to lessen the chance of infection, free the milk, and decrease its bacteria count. Their loan did not provide for a cooler to store the milk in between collections. In any event, a cooler might be impossible: the electricity provided to the area is so weak that the Lopezes have to disconnect their refrigerator, television and upstairs lights before they can turn on the milking machine motor. Lopez relies to a high degree on industrial feed for his cattle, rather than optimizing the yield on his pasture with quality seed and fertilizers, Villada says, eagerly showing me the charts documenting Irish farmers’ skillful use of similar land to produce cheap, good feed for their dairy cattle.

“But you see,” Villada concludes, leaning back and sighing, “only a few of us have been trained in advanced dairy farming techniques. There was a special program sponsored by the World Bank. We traveled to Ireland, New Zealand, Holland, and learned a great deal. Our pilot program with 500 farmers brought them up to Irish production levels in four years. But that program has ended now, and no more funds for training have been granted.”

Contrary to widespread Galician conviction, the government in Madrid is keenly aware of the difficulties Spain’s most backward region will face under the EEC regime. At the State Secretariat for Relations with the European Communities, technical advisor Jose Manuel Silva can list the problems by heart: primitive marketing systems; tiny and fragmented land-holdings; an aging and poorly trained population; overproduction of an item–milk–which is the EEC’s single largest headache; one million heads of cattle poorly suited to milk production and with a large incidence of tuberculosis and brucellosis. …He stops midstream to answer a question: “Yes, in principle, one can conclude that EEC entry will have a negative impact on the area. But,” he adds, “the structure of Galician agriculture has to change, with or without the EEC. Personally, I think that without some sort of deadline, without the traumatic mechanism that the EEC provides, Galicia will not emerge from underdevelopment. On the other hand, the impact cannot be too brutal, or it will generate enormous social problems.”

As Silva tells it, the government strategy for bringing Galicia successfully into the EEC appears predicated on an equal number of hopes and plans. He says that other milk producing regions will be oriented away from the product, to leave Galicia more of the national market. Galician farmers will be encouraged to branch out into sheep-rearing and produce, which have an open market in the EEC. Upon entry into the EEC, Galicia will be encouraged to sell milk to neighboring Portugal, which has an even more backward dairy sector. Upon entry, Spain will press for a sizable portion of the EEC’s Regional Development Fund. And “ecology” will be relied on to provide an essential part of the solution, by ridding Galicia of up to 50 percent of its agricultural population as the elderly die off while their offspring look for more profitable work elsewhere.

It is well to remember that under its current statutes, the Regional Development Fund, which is intended to strengthen Europe’s economically weakest regions, can only fund up to a maximum of 40 percent of projects already developed and approved by the member countries, and only as long as they do not contradict general Community policy. Diversification will also be at best a long-term solution for peasants who have been struggling for 20 years to bring one activity–dairy farming–up to modern levels. And in the ongoing economic recession, which has produced unemployment levels of over ten percent throughout Europe and more than 20 percent in Spain, it is by no means certain that the offspring of retirement-age peasants will choose to migrate. “That road is closed now,” says Pepe Lopez, who tried to find work as a dishwasher and construction worker in the industrialized areas of Spain after he was deported from Switzerland. Pepe does not trust the EEC, and he does not trust the government to defend his interests before it. He explained why in terms I was to hear repeatedly from Galician intellectuals and politicians, agronomists and radical leftists: “For Madrid, Galicia is not a part of Spain. They will bargain away as many of our interests as they need in order to get into the Common Market, and let Galicia be damned.”

For a less impassioned observer, the issue is different. Admission to the Common Market may be Spain’s last chance to become a full-fledged member of Europe. As a Spanish colleague in Madrid put it: “the question is whether Spain will have a chance to become like France, say, or whether we will remain ‘Europe’s Morocco’-a colorful exporter of oranges.” The Socialist government of Felipe Gonzales recognizes that access to modern technology and finance agreements, membership in NATO and EEC entry are geopolitically linked issues. In today’s depressed Europe neither the EEC nor the Spanish government have the resources to pour into a pain-free adaptation of rural Galicia to the world of international agribusiness. Along with marginally productive farmers in other areas of Spain–Asturias, Extremadura, and even highly developed Andalucia–Pepe Lopez and his family are part of Spain’s admission fee into the modern world. “We’ve taken a lot of blows, but we have always managed to carry on,” says Senor Jose.

©1985 Alma Guillermoprieto

Alma Guillermoprieto, a reporter on leave from The Washington Post, is chronicling changes in rural life under the policies of the European Economic Community.