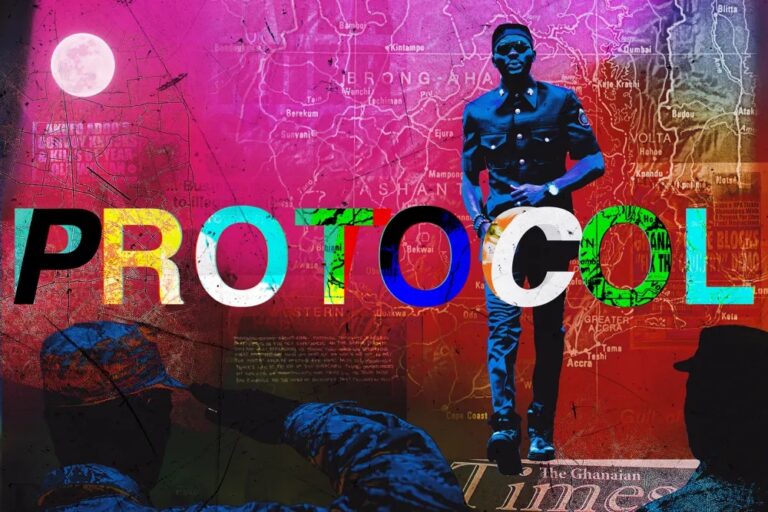

Special “protocol” treatment has become a way of life for the privileged few.

A friend recently told me a story about his attempt to get his first dose of COVID-19 vaccine in Accra, the capital of Ghana. When he arrived at the distribution center, he was instructed to join a line outside. An attendant gave each person a number to ensure there were enough doses for everyone. Then a familiar scene appeared: A trickle of cars was ushered into the compound, one by one. Soon afterward, the attendant informed my friend that the facility had run out of shots.

In Ghana, the inside connection that likely allowed the people in the cars to skip the vaccine line is called protocol, or “proto” for short. Paradoxically, protocol often means expedited access that circumvents established procedure. People in Ghana do not follow protocol; they have it, through kinship or a social connection. One might use protocol to quickly access a public service, while applying for a job, or to get into a good school. Its prevalence reflects how equal rights and access are becoming a mirage in Ghana, fueling disillusionment with the government and the country’s supposed meritocracy.

Although my friend was irritated that he couldn’t get a vaccine, the situation wasn’t a surprise. Family group chats, church WhatsApp groups, and alumni associations across Ghana are all buzzing with people asking if anyone has protocol in one place or another. Insiders openly advertise “protocol vacancies” in the government and military. While waiting to renew a driver’s license or passport, it is common to see a protocol group standing apart from the regular line. They aren’t sure where they’re going, but they are secure in getting what they came for.

For those without protocol, routine bureaucratic interactions have become a point of stress. Its normalization means that people seeking a service the normal way may feel like second-class citizens—even if they came first. But many Ghanaians have largely accepted the system, even as they complain about it. One Twitter user noted that without protocol, it takes months to get a copy of one’s birth certificate. I’ve seen another joke that the ubiquity of protocol means one needs it to make new friends in Ghana.

Beyond individual concerns, the protocol system threatens to undermine Ghana’s state institutions, which are already perennially underperforming. It casts doubt on the meritocratic idea that government staff are recruited because of their abilities and increases the likelihood of other protocol hires. After recent revelations that Ghanaian police officers were involved in the robbery of armored vehicles drew attention to the police recruitment process, Modern Ghanacolumnist Stephen Atta Owusu pointed out that protocol hiring could even increase security risks.

Anakwa Dwamena is a 2022 APF fellow, examining how climate change and democracy is playing out in West Africa.