Story by Andrew Meier with photographs by Mia Foster

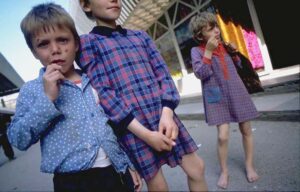

Tiraspol may be the bleakest of cities in the former Soviet Union. A gray town of some 50,000 beleaguered souls, it has not witnessed the destruction visited upon the Chechen capital, Crozny, nor the chromosomal damage that haunts the irradiated zones in nearby Belarus and Ukraine. But life in Tiraspol, the capital of the self-proclaimed “Transdniestrian Moldovan Republic” (known in its Russian initials as the “PMR”), is just as hard. When the Russians who predominate here declared their intention to break free from the former Soviet republic of Moldova, an armed conflict ensued in the summer of 1992. Five years later, life in this implausible mini-state has approached its minimalist limits. Crossing its threshold is reminiscent of entering East Berlin, circa 1980.

Frozen in the darkest days of the Soviet era, Tiraspol is an island of absurdist propaganda, Lenin statues and fear. Its factories are closed, streets empty and dingy state stores bare. But this time socialism Politburo-style is not to blame. For Tiraspol is under siege, and the enemy is a criminal regime of alien occupiers that clings to power by fear and force.

The trouble in Transdniestria began, just as in every regional argument in the former Soviet lands, in the last days of the USSR. However, its roots, not surprisingly, grew out of Stalin’s map. Moldova is small nation with a long and tangled past. Most of it was once part of Romania, occupied by the USSR in 1940 under the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, sealed in secret by the foreign ministers of Stalin and Hitler. Transdniestria, a sliver of land on Moldova’s eastern edge wedged between the river Dniestr and Ukraine, is the significant exception. It once belonged to the land to the east, Ukraine. Never part of an independent Moldova or Romania, Transdniestria has been inhabited by ethnic Romanians since the late Middle Ages. But thanks to the Soviet practice of Russification, Russians were lured into the province and handed the top jobs in its abundant factories and state offices. Transdniestria, with its heavy industry and Party apparatus, became Moscow’s loyal outpost in the southwestern corner of the USSR, a reliable lever against the volatile Romanians.

Thus sliced off from Romania, Moldova was the only Soviet republic with a “mother country” outside the USSR. Despite Moscow’s perverse efforts to fabricate a Moldovan culture distinct from Romania’s, the language, religion and wines of this pastoral nation of 4.5 million remain true to their pre-war lineage. The Conflict – as both sides have christened the wound that has rent Moldova – first stirred when the 43% ethnic-Romanian-speaking majority began to defy Moscow, denounce their ethnic Russian compatriots, and as the Soviet empire crumbled, call for reunification with Romania. The fear in Tiraspol, not entirely unfounded, was that Russian speakers would be denigrated in the new order. The independence rallies in Chisinau did yield an unforgiving nationalism, as a new mantra rang out – “chemodan, vokzal, Rossiya,” “suitcase, train station, Russia” – giving the Russian population their marching orders. And so, in Transdniestria, the ethnic Russians grew convinced that only separation from Moldova could save them from Romanian reunification. In September 1990, under the specter of a rising Greater Romania, Transdniestria declared its independence.

The leadership in Chisinau, the Moldovan capital that lies a short drive from Tiraspol, sought to halt the secession of their industrial engine – and the province that hosts Russia’s heavily-armed 14th Army. Thus, in the spring of 1992 when the Russian troops distributed arms to local militias in the PMR, The Conflict ensued with the sides squaring off along the Dniestr. In Moscow, the failing heart of the Motherland, Communists embraced the PMR as their last resort: a small, but pivotal battleground for the revival of the USSR. With the support of the Red-Brown factions in Moscow, the Tiraspol separatists set out to claim their land. The battles of the summer of 1992 were brief. Peace was restored by General Alexander Lebed, who as commander of the 14th Army, marched both sides to the cease-fire table. Lebed, as he would later recall, stemmed the bloodletting with characteristic bluntness: “I told the hooligans in Tiraspol and the fascists in Chisinau – either you stop killing each other, or else I’ll shoot the whole lot of you with my tanks.” By August 1992, a tripartite peace-keeping force of Russian, Ukrainian and Moldovans was in place and has monitored the cease-fire ever since. The PMR, however, crawls along, having taken on a new nickname, in honor of its corrupt regime, in Moscow’s liberal dailies: “Haiti on the Dniestr.”

When the history of the first post-Soviet decade is written, the fight for Transdniestria is not likely to loom large – and deservedly so. The fraternal war in Tajikistan took tens of thousands more lives. As did the battle for Chechnya. The war over Nagorno-Karabakh took a high human toll and renewed feuds that reverberated East and West. To many, “The Conflict” in Moldova does not even rank as a war. By the standards of the regional conflicts that raged across the old empire, a few thousand men, taking aim at one another with old Soviet rifles from the muddy banks of one of Europe’s forgotten rivers, do not measure up impressively. In the bloody calculus of post-Soviet independence movements, the body count – though still disputed – was comparatively low. (Even the most bitter on both sides say no more than a few thousand died here.) As a spectacle of combatants, Transdniestria may have trouble making the history books, but The Conflict deserves attention. For only here, along the southwestern flank of the old USSR, did Russians take up arms to fight for their independence. Moreover, Moldova became the first target of Moscow’s military intervention in its old Soviet backyard. Today, Moldova remains the last country in Europe to suffer the humiliation of hosting Russian troops – despite a 1994 pact signed by Moscow promising their withdrawal.

By now, the euphoria of the PMR’s first days is long gone. Transdniestria has paid dearly; instead of independence, it has isolation and dependence on an ailing Russia. Its 720,000 residents face a frightening, and increasingly obvious, conclusion: their sovereignty is untenable. Most salaries have dipped below $10 a month, paid out in bank notes freshly printed in Germany. Inflation is so high, the printers cannot keep pace. “You have to imagine another zero on the end,” explains one resident, pointing to a new 50,000 note. “As soon as these hit the streets, they became 500,000 ones.” Despite the preponderance of evidence, the defiant souls of Tiraspol remain devout believers in their separatist dreams.

“How dare you come here to interrogate us!,” spits a pensioner in a frigid bakery, as she waits for her ration of bread. “Don’t you try to tell us how to run our country.” Some country. Transdniestria, in the post-Soviet parlance of diplomats and journalists, is but a “breakaway region.” Except for generals in Moscow, Kremlin-watchers in the West, and future biographers of General Lebed, the backwater is unknown. But if you ask the rogues who run it, their sovereign state deserves worldwide recognition with all the trimmings – a seat at the U.N., World Bank transfusions and emissaries in foreign capitals.

“We had every right to found our republic, we were forced to protect our future,” insists Grigoni Marakutsa, chairman of the ‘Supreme Soviet’ in Tiraspol. “If we hadn’t, we would be speaking Romanian and living under some king in Bucharest.” Once upon a time, afloat on the wave of independence, Marakutsa and his underemployed ex-Party cohorts were full of grand plans. Having staved off the Romanian onslaught, they would revive Russia’s military might and craft a new national identity. Their Grail? Nothing less than the resurrection of the Soviet Union. By now these hopes have faded into a vapid recitation, declaimed to visiting journalists and the local population alike, in the face of the obvious shortfall. The PMR’s failure to meet its first 5-year plan is fittingly illustrated by its new currency, adorned by the visage of the province’s patron saint, Tsarist General Alexander Suvorov. The separatists boasted that their little republic would become, as it had been in Suvorov’s day, a bulwark for the empire’s defense. But today their currency – at 700,000 “Suvorovki,” as the notes are nicknamed, to a dollar – is nearly worthless.

The PMR’s chieftains, however, have grown fond of ruling. They reign over a private fiefdom, replete – thanks to the bridges along the Dniestr blown up during The Conflict – with its own moat. Moldova, meanwhile, has elected a new president, Petru Lucinschi, a moderate progressive, especially, for a Politburo veteran. Lucinschi put the restoration of Moldova’s territorial integrity and the removal of the remnants of the 14th Army – some 6,500 men – at the top of his agenda. “Deadlines have come and gone,” Lucinschi said, “but sometime dialogue must turn into deeds.” For five years Moldova has pleaded with Russia to remove its troops. Washington has seconded Chisinau’s entreaties, as has the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). But Moscow has stalled. In 1994, after Gen. Lebed’s departure, Moscow did “restructure” the l4th – rechristening it the “Operational Group” – trimming its troops and packing up some their Red Army surplus. “They changed the name, but not much else,” says a Western diplomat in Chisinau.

Moldova has reason to be impatient. While its agrarian economy is hardly flourishing, amidst the bedlam of the former Soviet lands it is doing well. Inflation is down, and this year there is renewed hope that its fertile fields will again bear the fruits that earned Moldova the reputation as the orchard of the Soviet Union.

Transdniestria, five years after the guns have cooled, offers an elucidating mirror image of the secessionist struggle in Chechnya. In Chechnya, Moscow could not brook the centrifugal urgings of the Muslim rebels. Yet when the Russians in Tiraspol decried the (anticipated) sufferings promised by a sovereign Moldova, Moscow adopted them as “patriots.” More than politics underlies Russia’s support. The 14th Army was built as the Soviet firewall against the Balkans. “In the doomsday script,” says Colonel Mikhail Bergman, Commandant of Tiraspol, and Lebed’s loyal adjutant, “the 14th was to pave the way through Romania into southwestern Europe.” And so, Moscow made sure it was well-stocked. The arsenal remains large – and dangerous. Some of it dates from the 1930s, all is under uncertain guard. “They’d sure make some fine firewood,” said one Western diplomat. A NATO analyst offers a lengthy (if incomplete) inventory: “121 battle tanks, 288 armored personnel carriers, 6 armored vehicle-launcher bridges, 7 combat helicopters, 36 anti-tank guided missile launchers, 129 artillery systems and some 450,000 automatic weapons, and several million pieces of ammunition for artillery.” The PMR has yet to grant access to the OSCE to inspect the materiel depots in the town of Colbasna near the Ukrainian border.

The Russians complain that they lack the means to ship out these stockpiles, claiming 11,233 railway carriages are required. In Transdniestria, however, ethnic Russians insist that the presence of the Russian troops is their only guarantee for peace. Lebed was so beloved here that when he took leave of Tiraspol in 1994 to enter the political fray in Moscow, a group of women blocked the tarmac in Tiraspol to prevent his replacement, Lieutenant General Valery Yevnevich, from landing. Forced to land at a reserve field, Yevnevich had to helicopter into his base. Asked for his assessment of the present stalemate, the General failed to be as forthcoming as his predecessor: “Don’t you worry, the situation is under control.”

Perhaps, but whose control? For despite Stalin’s successful perversion of native demographics, ethnic Russians comprise just 25% of Transdniestria’s population. However, they have monopolized the province’s political and security structures. Ethnic Moldovans may make up over 40% of the populace, but dispersed throughout the rural province, they have no representation in Tiraspol. Ethnic Ukrainians, 28% of the PMR, fall somewhere in between: tolerated as fraternal Slavs, but expected to heed the call to arms should the Romanian beasts rise again.

These days, however, you would be hard pressed to find anyone on either side of the Dniestr who still believes ethnicity incited The Conflict. “We were all fearful of ‘ethnic conflict,”‘ recalls Lyudmilla Skalnaya, head of the Moldovan Women’s Association, one of the largest organizations in the country. “But we’ve learned that we were mislead – by the disinformation on Russian state TV and by our own ambitions. Look around, who wants to join Romania? By now it’s clear to both sides: this was a political conflict.” As a political dispute, the cause could easily be manipulated, and in Tiraspol, hijacked by a handful of minor despots.

“It’s not Soviet socialism any more,” says a Western ambassador, struggling to articulate Transdniestria’s form of governance. “It’s a cleptocracy.”

Transdniestria is ruled by a band of venal chieftains, widely believed to be corrupt to their core, masquerading as defenders of the Motherland. “Whatever it is that exists over there,” says Donald Johnson, the head of the OSCE mission in Chisinau, “it’s not a subject of international law – it’s some kind of nightmarish Disneyland.” Another diplomat tries to be delicate: “There seems to be a divergence of objectives between the population and the regime.”

The PMR regime resembles a band of minor devils risen from the surrealist pages of Gogol and Bulgakov. One of the chief protagonists, “Mephistopheles,” as Colonel Bergman calls him, is one Vadim Shevstov. With his goatee and bulldog scowl, “Major General” Shevstov rules Transdniestria’s “Minister of State Security,” the boss of its reinvigorated KGB – estimated to employ some 5,000. Shevtsov bears more than a superficial resemblance to Goethe’s seducer. For, as Bergman and Lebed revealed with great drama, before migrating to Tiraspol Shevtsov was Vadim Antyufeev, a long-term servant of the Latvian police during the Soviet era. For months after his unmasking Shevstov reigned in denial. With good reason: he remains a wanted man in Latvia. In Riga, during the failed coup against Mikhail Gorbachev in August 1991, Antyufeev had taken part in the bloody crackdown, in a vain attempt to prevent the Latvians from slipping their Soviet bonds. In Tiraspol he found a haven – and a promotion. Igor Smirnov, former director of one of Tiraspol’s factories, may be the PMR’s “president,” but Shevtsov controls its streets, press, and, as his more brazen servants will tell you, protection rackets. “It’s no secret to anyone who lives here,” says Col. Bergman, “that this disguised criminal and his bandits are running this place into ruin.”

Yet even Shevtsov’s grip cannot strangle all dissent. There is, for example, one critical voice on the airwaves. “I can’t say it’s been easy, but we’re still alive and working,” says Eric Abildaev, 28-year-old director of TVK-Asket, the lone independent media outlet in Transdniestria. Since its founding in 1991, the station – a jumble of rooms in a decrepit dormitory – has witnessed the wrath of Shevtsov’s forces, who have more than once tried to close it down. Yet even in the PMR, the truth – however inconvenient – reverberates. TVK-Asket, known for its bold broadcasts during The Conflict, has attracted a loyal following. At the same time, across town 668 children attend the only Romanian school in Tiraspol. “The Moldovan language is taught in our schools,” insists the parliament chief Marakutsa. But he fails to add that it is taught in Cyrillic, the alphabet of the Soviet empire, while Moldova long ago restored the language to its native Latin script. “No one protects us,” says the school’s director, Ion Iovchev. Like Abildaev’s station, more than once, the school has suffered the abuse of its critics, its windows smashed and walls defaced by vandals. “We know our work is not appreciated,” says Iovchev. “But the century is nearing its end, and we must keep our language, if not ourselves, alive.”

Although the cease-fire has held, this summer as The Conflict marks its fifth anniversary, a political stalemate endures. A draft agreement, “The Memorandum on Normalization of Relations between Moldova and the PMR” – dubbed “the Memorandum” – was to be signed by Chisinau, Tiraspol and Moscow last July. But when the day came for its Kremlin unveiling, one of Boris Yeltsin’s recurrent heart attacks ruined the schedule. Then, given Moldova’s fall presidential campaign, no one in Chisinau rushed to sign it. The Memorandum thus remains unsigned.

“This is not an unsolvable conflict,” insists the OSCE’s Johnson. “This is not about generations of hatred built up over the years. There aren’t tens of thousands of victims for whom blood feuds have to be paid. This is a political deadlock. And it’s about high time someone made a move.” This year, at winter’s end, that move may have come. During a secret stopover in Chisinau, Yuri Baturin, the head of Yeltsin’s Defense Council, promised Lucinschi Russia would cut its troops in Moldova to 2,500 this year. The troops, however, may not go quietly. For most, like Col. Bergman who was born in Tiraspol, are natives to the province. Moscow, moreover, may not be willing to part with its Transdniestrian trump card. Days before reassuring Lucinschi, Baturin ventured into the PMR to cheer the Operational Group of Russian Forces – as Moscow has rechristened the 14th Army. At a closed meeting with Gen. Yevnevich and his boys, Baturin assured them they would stand guard until a political settlement emerges. In other words, indefinitely.

While the Russians may be tacking toward conciliation, the rogues in Tiraspol are anchored in revolt. After Baturin’s visit, “President” Smirnov broke off negotiations with Chisinau and the OSCE. “Outraged and shocked” by a recent OSCE report on Transdniestria, Smirnov shrieked that the cold war had flared again. The OSCE report, he protested, maligned the PMR thanks to “America’s determination to undermine Russia.” His proof? “Johnson is an American!” he screamed to the Red-Brown press in Moscow. The attack on the Ambassador was well-earned. In contrast to most diplomats in the region, who for years have tolerated Transdniestria’s wastrels in muted protest, Johnson made a stand. The OSCE report detailed the PMR’s illegal introduction of military posts and banned weaponry – Soviet GRAD missile-launchers, for instance – in the demilitarized zone along the Dniestr.

The Ambassador also noted Shevtsov and company’s refusal to grant Moldovan and OSCE monitors access to suspected military sites. Moreover, Johnson had the temerity to recount Tiraspol’s refusal to allow Transdniestrians – who remain, after all, Moldovan citizens – to vote in Moldova’s presidential elections.

Smirnov and Shevtsov, thankfully, do not speak for the PMR’s majority. By now, the veterans of Transdniestria’s battles are left with one dream: that the lives felled on the banks of the Dniestr not be relegated to obscurity, buried as post-Soviet footnotes to absurd ambition and nationalist extremism. If only Shevtsov and Smirnov lose their Moscow patrons, posit the optimists in Chisinau and Tiraspol hoping against hope, reason and compromise may just prevail. The key to closing The Conflict, they say, lies in Moldova’s new constitution. “It’s colossally liberal,” says a U.N. official, of the document that would grant Transdniestria ‘special status’ within the republic.

Isolated and rotting, the PMR, however, may be nearing its end. The regime has failed to lure any foreign aid or investment, let alone recognition. Tiraspol’s residents have been reduced to hunter and gatherers. Any new shoots of private enterprise – for even Tiraspol cannot stave off the intrusion of post-Soviet commercial impulses – succumb to Shevtsov and his enforcers who control the little trade trickling in from Ukraine. Moreover, Moscow may have lost its appetite for subsidizing its fraternal outpost. Last year, unable to pay wages or pensions, and perhaps sensing the end approaching, Smirnov proclaimed a state of emergency, enhancing the powers of Shevtsov’s militia.

Moldova, meanwhile, yearns to define its nascent statehood, to unburden itself of Romanian and Russian fealties. “Moldova is pretty independent, because no one depends on it,” quips Dima Solovyov, a young Russian journalist in Chisinau, who spent the summer of his 21st year driving up and down the Dniestr counting bodies during The Conflict. But Moldova, lying at a vital crossroads between the Balkans and the old Soviet lands, has been dealt a tough draw. It yearns to repair its borders and social fabric, but at what cost? “The time for settlement has come,” says Lucinschi. “We’ve grown up since our first days of freedom. We’ve become Europeanized and now we’re ready to take a seat at the European table.” His republic, however, remains caught in a Russian bearhug, reliant on Moscow for 98% of its energy. Its internationally recognized independence, some have noted, is seasonal: sovereignty depends on how well the fruits and grapes grow. Tucked away in one of Europe’s unknown corners, Moldova would simply prefer to be left alone. “We don’t need to join NATO,” Lucinschi assures, “but neither do we want to become a buffer zone between an enlarged Western alliance and an unhappy bear.” For a borderland suffering an open wound, and forced to shelter the servants of an alien army, the choice is unenviable.

©1997 Andrew Meier

Andrew Meier, a correspondent with Time magazine in Moscow, has been examining the fate of the former Soviet republics.