Story by Andrew Meier with photos by Mia Foster

TAJIKISTAN – It had been a lovely afternoon drive through the mountain passes of this small Central Asian state. As we made our way along the craggy reaches of northeastern Tajikistan, the greatest threat had been the stretches of the dirt road that had washed away in the heavy spring rains. We had just navigated a narrow valley littered with the detritus of yet another battle in the four-year-old Tajik civil war. On a deserted field battered and burnt tanks lay scattered as monuments to an opposition victory. But the rebels had not held this ground long, and within a month they had been forced back to their perches in the surrounding mountains.

Now the government forces were back in charge. The road was open and safe, it seemed, to traffic. But here along the remote roads of this beleaguered nation of 5.9 million, as in so many of the war zones of the former Soviet Union, security can be a fleeting sensation. Each checkpoint brings new worries, and the one at Sicharog that afternoon in mid-May proved no exception.

“Get out of the car!” demands the teenaged soldier, one of a half dozen stranded at this post, left on their own with little food and shelter to guard their lonely stretch of the valley. “Get out and show us your documents!” he screams again. But there is question about the wisdom of exiting the vehicle. “Once they pull you from the car,” a seasoned aid worker had explained back in the capitol of Dushanbe on the eve of our journey to the front, “your chances of survival diminish dramatically.”

The checkpoint at Sicharog is no different from hundreds of others scattered along the dusty roads of Tajikistan. But it is worth describing. The post is nothing more than a dark hut. Nearby sits a disabled armored personnel carrier sinking into the thick mud. In the trees behind it, you can make out a pair of gunners’ positions, haplessly camouflaged with sparse branches. One perhaps has a stationary machine gun with enough ammunition to feed it for a brief firefight. Were it not for their location and hardware, the boys assembled here would be hard to recognize as soldiers. Some wear tattered Red Army surplus, others just t-shirts and track suits, the ubiquitous uniform of post-Soviet irregulars. But all wield Kalashnikov machine guns, of various vintage and prowess.

There is no evidence of danger here, but this bend in the road at Sicharog – which in prewar days must have served as a crossroads for goats and sheep and tired travelers heading into the capitol – is filled with fear. For we are all trapped here at this checkpoint. The soldiers have to stop us, and we have to obey. We are stuck here together, in the middle of Tajikistan in the middle of the fifth year of a brutal civil war that has now been down-graded by the U.N.’s military experts to a LIC – a “low intensity conflict” – from its early peak in the summer of 1992. Then, in their newfound independence from the deceased Soviet empire, tens of thousands of Tajiks were slaughtered under the banner of many causes, at the behest of many warlords. The war has left both sides exhausted and divided and fighting harder for less of the diminishing spoils.

Oddly enough, just a day before this stretch of the road had offered a bucolic scene of young men bathing in a stream, while others wrung out their soaking uniforms. Then they had seemed like strong young men. Now up close they looked like scared young boys, reeking of vodka and high on a crude local cocktail of wild herbs and perhaps, opium.

“We’ve been hit,” the youngest one explains in broken Russian. “By them,” he says as he tilts his gun to the surrounding hills. Opposition fighters had attacked at 5 a.m. that morning, killing six of the boys at the checkpoint, and wounding their commander. No wonder they are scared. Left on their own to defend their embattled government’s tenuous hold on this remote mountain region, it’s no wonder they are blitzed beyond cognition.

The heart stops briefly at each of these checkpoints. It is as if the body is making good use of the time to measure its pulse. Still working, yes. But for how much longer?

After a brief exchange, a bearded sub-commander has taken charge, inserting himself between his younger charges and those in the car. His words are unintelligible, and his grip uncomfortably firm. But at last I hear him mumble the welcome phrase, “Rokhi safed!” – “Safe Travels!” – while his junior partners shout out in broken Russian, “Get out of here. Not safe. Get out!”

Spring is the season for fighting in Tajikistan.

“When the snows melt,” an opposition leader in exile in Moscow told me, “the boys come down from the mountains to continue the cause.”

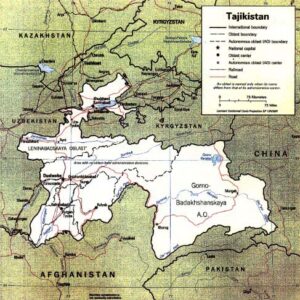

Right or wrong, that cause has carried an enormous cost. Of all the former Soviet republics, none has fallen further or faster than Tajikistan, a small, mountainous state lodged in the heart of Central Asia between Afghanistan, China, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Always the poorest republic, in the final year of the U.S.S.R., Tajikistan delivered less than 1% of the total Soviet gross national product. Since gaining independence in 1991, Tajikistan has suffered even harder. Now it is a land in limbo. The neo-Communist regime of President Imomali Rakhmonov may control the corridors of power, but much of the country remains beyond its reach, and the work force that once harvested its vast cotton fields has been reduced to anemic hunters and gatherers.

The war had a simple start, but its roots – stretching back to the inception of Bolshevik rule here in 1929 – are long and difficult to trace. Political violence broke out in the spring of 1992, as the country floated rudderless in the sudden freedom from Soviet control. Seven candidates contended in Tajikistan’s first presidential election in 1991. In a vote that was widely disputed, the Communist Party claimed victory over Davlat Khudonazarov, a film-maker and secular liberal. In the months that followed, the tensions that arose during the election spawned a civil war that ranks among the most violent in any of the former Soviet republics – with as many as 50,000 Tajiks dead and an estimated half million more forced to flee their homeland. The secessionist struggle in Chechnya may have garnered more headlines, but the Tajik body count rivals, if not exceeds, the Chechen figure.

The conflict has been routinely characterized as “ethnic.”But the war followed the country’s traditional regional fault lines. “This has always been a battle among regional forces,” says Gantcho Gantchev, head of the Tajik mission of the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). “After all, they’re all Tajiks.”

Who is a Tajik and what is Tajikistan, however, is a matter of considerable contention. Before the Bolsheviks seized power here in 1929, there was no Tajikistan. The area where “Tajiks” lived, then belonging to the emirate of Bokhara, had been a bulwark of the Islamic resistance to the Communist Revolution. Only Stalin, in true form, drew up the artificial borders of Tajikistan. In defining a nationality largely based on the Tajik language, which is nearly identical to Farsi spoken in Iran and Afghanistan, Stalin had to shift its script from Arabic to Cyrillic.

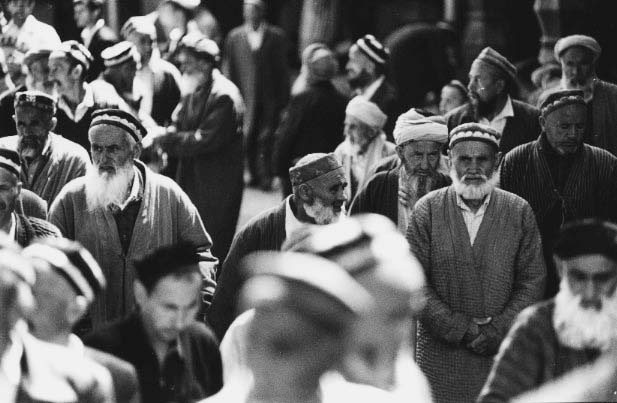

Despite the foreboding Stalinist facades of Dushanbe’s state buildings and the Moscow’s efforts to dilute the Tajik culture and language, the Tajiks managed to stave off complete Russification. Lenin died before the Bolsheviks finally wrested control here in 1929 from the defiant partisans in the mountains. Even now, as Tajikistan once again embraces Russian domination, the look of the land remains distinctly non-Soviet. In Dushanbe weeping willows limn “Lenin Park,” chenar trees line its broad avenues and women still wear their traditional brilliant dress. Men greet one another – with their hand on their heart – with the gracious salutation, “Asalaam alecheim,” “May peace be in your house.” Despite six decades of Soviet rule, the Tajiks’ eastern ways have survived with a defiant grace.

“Part of our burden is that we don’t know who we really are,” explains Gavhar Juraeva, who with her husband, Khudonazarov, has been forced into exile in Moscow. “Tajikistan stands at the crossroads between Asia and the West. We’re an ancient people. But we’re still not sure if we’re really Asian or European.”

As the fronts followed regional – and not ethnic – lines, it was hard even for the combatants to identify their enemy. While Gharmis and Pamiris speak a distinct dialect of Tajik, which is itself closely related to Dari. But their features reveal an ancestral mix of the Indo-European, Turkic and Mongol tribes and traders who roamed the region centuries ago and trekked along the silk route from China through Central Asia to Europe. In appearance alone, Gharmis and Pamiris are often indistinguishable from the natives of other regions. “In Dushanbe, we had to wear different color bandanas just to tell who was who,” recalls one fighter from the victorious Popular Front.

Religion also failed to unite the Tajiks. While most are Sunni Muslim, the Pamiris are Ismaili. “But the real religion here is popular Islam,” says Guita Ranjbaran, an American anthropologist doing research here. “The Tajiks themselves aren’t sure what they believe, although they all say they’re Muslim.”

So as the U.S.S.R. crumbled, Tajikistan had no foundation myth to rely on. Instead the war pitted the powerful and weak groups – created by Moscow during the Soviet era – from the north and south, mountains and valleys, against each other. Those who perceived themselves as victims sought to redress the gross economic imbalances between the developed north and impoverished south. On one side were the people from the provinces of Leninabad (since renamed Khojand) and Kulyab, who dominated the State nomenklatura and the Communist party during the Soviet era. While the Khojandis are predominantly ethnic Uzbeks, their alliance with the Kulyabis revealed a hunger for power greater than any ethnic enmity. The opposition formed around a loose coalition of aggrieved social and regional groups. First among them were the beleaguered Gharmis, past and present residents of the remote Gharm Valley whom Stalin forced to the south to irrigate the cotton fields in the 1940s. The Pamiris, people from the mountainous region of Pamir, joined the Gharmis to fight alongside a melange of secular nationalists, Westernizing intellectuals and Islamic leaders for a share of the government after having been shunted aside for so many decades of Communist rule. But the opposition was never certain which banner to bear; some yearned for more Islam, others for more openness, and some for more personal power.

The war was distinguished by atrocities on both sides, but its lasting legacy lies in the south, where the mud-brick kishloqi, the villages scattered among vast cotton fields, became killing fields. The conflict destroyed a vast swath of the south, as the victorious Popular Front (led by a brutal vanguard of well-fed and well-armed fighters from the Kulyab region) seized and burned village after village of Gharmis and Pamiris. Cleansed of undesirables, today many of these kishloqi have been bulldozed beyond recognition, let alone for use as habitation for the trickle of refugees returning from Afghanistan, Russia and the neighboring Central Asian states.

By now the large-scale bloodletting has ebbed. Except for a periodic cycle of political assassinations in the capitol, the fighting is isolated around the town of Tavildara in the foothills of the Pamir mountains. The regime is hanging on, but only in the shadow of Russian tanks. Russia’s 201st Motorized Rifle Division, boasting the highest-paid officers in the Kremlin’s forces, is oversubscribed. In Boris Yeltsin’s revision of the Brezhnev Doctrine, Russia is here – with 25,000 troops – to secure a sphere of influence in its so-called “near abroad.”

A ceasefire signed in September 1994 is broken almost daily. The peace talks sponsored by the U.N. are now in their fifth round, without yielding any significant results. “We’ve come to the limit,” says Gantchev. “We now face the dilemma of having political agreement or not.” The government is opposed to any sharing of power, while the opposition insists on scrapping both the parliament and the present administration to establish a National Reconciliation Commission. The envisioned coalition would then revise the constitution and run the country during a transitional period before new elections.

“But the government says the constitutional reform’s already been done and no changes are needed,” says Davlat Khudonazarov. “They’ll accept new elections for president, but only if organized by them.” After receiving numerous death threats and spending a year at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., Khudonazarov has returned to Moscow, where he openly scorns both sides of the Tajik conflict. “By now they’ve both been corrupted by blood and money,” he says. “They’re fighting only for their own survival, just to get more money from their sponsors – whether they be Russian, Uzbek or Arab.”

As the conflict continues, and the peace talks yield neither peace nor political concessions, many in Dushanbe have begun to worry that the U.N. may pull out altogether. “That would be bad for all the parties involved,” says Shilovic, the Croatian head of the U.N. mission here. No one is more frustrated by the political deadlock. “We are only facilitators,” Shilivoc says. “So what can we do? We sit here and we write reports.”

Both sides are playing a crude propaganda war. The opposition accuses the regime of wholesale corruption and illegitimacy, while Dushanbe and Moscow denounce the rebels as drug runners and Islamic fundamentalists. “The Islamic opposition is set to continue their partisan war,” Lt. General Pavel Tarasenko, the ruddy-faced commander of Russia’s border guards stationed here, told a Tajik newspaper recently. “All armed groups who try to cross into Tajikistan will be thoroughly eliminated,” he assured his attentive audience.

But the general’s confidence leans heavily on wishful thinking. Since 1992, opposition rebels have attacked the Russians who guard the 900-mile Afghan-Tajik border more than a hundred times, and there is no sign of their abating. In retaliation for the raids, this spring jets bombed two villages in northeast Afghanistan, alleged nests of Tajik rebels, reportedly killing 6 civilians and wounding 15. Moscow denied any involvement in the sorties, while a U.S. State Department official coyly noted that “the planes fly at night and the pilots are careful not to talk over the radio.” But reports in Afghanistan point to the Russian hand. “No doubt about it,” said a U.N. aid worker who found himself in one of the villages during the bombing, “these jets were Russian.”

As the war lurches on, the government has had to rely heavily on Russian support and domestic repression. By now, Rakhmonov’s regime has earned a reputation as the most totalitarian to arise in the wake of the Soviet empire. Nearly all of the country’s dissenting politicians, poets, and journalists have been silenced – either by prison terms, exile, or assassination.

“Democracy here is a farce, the human rights record is disastrous,” says a U.N. source with unusual candor. “It’s an oppressive, autocratic, dictatorial regime – that has been recognized by the U.N., by all the countries in the region and in fact by all the countries in the world.”

Tajikistan has also been recognized as the most dangerous place in the world for journalists. Forty-one have died here since 1991, according to the Foundation for the Protection of Glasnost in Moscow. Abdulfyattokh Abdurakhmon, 36, runs “Istiklol,” or “Independence,” Tajikistan’s only non-governmental, non-tabloid newspaper. Since February his staff of three has managed to run off four issues – 2,000 copies, four pages each – on the state presses. The fifth issue is ready, Abdurakhmon points out, and has been for weeks.

“But with no newsprint to buy, the news is getting old.”

Given the regime’s dislike for bad news, Istiklol’s survival – even for a few months – is no small feat. Abdurakhmon remembers well the heady days of glasnost, when “the kiosks were full of so many papers, so many views.” But “once they started to hunt journalists,” he recalls with a shrug, “suddenly papers began to close.”

Journalists are not only ones in Tajikistan to meet early ends. In January, on the first day of Ramadan, Tajikistan’s highest religious official, Mufti Fathullo Sharifzoda was killed in his home in Dushanbe along with four family members. In May, the director of Dushanbe’s medical institute and his deputy joined the ranks of the capitol’s high-ranking murder victims. By now the routine for each case is scripted: an official investigation is launched, but never completed, no suspects are found and no forensic details come to light, but the incriminating rumors fly far. While assassinations once served to stall negotiations, as crime spirals upward in Dushanbe, the murders no longer seem purely political. As one Tajik journalist put it: “Before, we all knew why someone was targeted. But now who knows what kinds of business is involved?”

Rising crime is but one of the problems facing the government on the home front. “It’s becoming harder and harder for them to keep the troops fed, let alone happy,” says Thomas Merkelbach, director of the International Committee of the Red Cross mission here. Not surprisingly, earlier this year the regime faced a two-headed mutiny within its own armed forces. In the western town of Tursun-Zade, Ibodullo Boymatov, the local commander, denounced the “mafia surrounding Rakhmonov” and called for their removal. Boymatov, an ex-taxi driver who rose to power as a Popular Front commander, is an ethnic Uzbek, who reportedly speaks no Tajik. At the same time, the commander of the regime’s first brigade, Makhmud Khudaberdaev, brought his troops and tanks from their southern base in Qurgan Teppa to within ten miles of the capitol to challenge Rakhmonov into sharing the spoils of the war.

In “le petit putsch,” as one French aid worker termed it, Dushanbe waited nervously before Rakhmonov blinked and acceded to his insubordinate commanders’ demands. As the internal power struggle mounted, the Russians finally managed to keep the peace – in Dushanbe at least. “If it hadn’t been for the Russians,” says a Western diplomat. “We would have had the civil war against the Kulyabis this time.

Since the victory of the Popular Front, tension had mounted between the Kulyabi and Uzbek factions of the victorious coalition. After they took power, the Kulyabis united the southern regions of Qurgan Teppa and Kulyab into one province, depriving ambitious Uzbeks in northern Tajikistan of a southern power base. The Uzbeks, in turn, have had to watch as Kulyabi warlords looted the country’s diminishing resources. “It’s a natural internal struggle after a victory,” says the OSCE’s Gantchev.

At the same time, the insurgent forces in Tavildara have steadily gained ground, nearly 30 miles at one point this spring, and reportedly taken several hundred government soldiers prisoner. During the recent fighting, the rebels captured a string of villages and severed the sole highway connecting Dushanbe with the eastern province of Gorny-Badakhshan.

While figures are hard to confirm, in June helicopters delivered a half dozen wounded soldiers almost daily to Dushanbe. “Our boys are hurting in those hills, ” admitted one high-ranking government officer charged with securing Tavildara. “It’s not an enjoyable business of bringing home bodies,” he said after riding one of the choppers back to the capitol. During the increased fighting in June, according to U.N. estimates, as many as 300 government soldiers were killed, 400 wounded and 750 taken captive.

“There’s no way the government wins up there,” predicted an American diplomat in the region. “No way, that is, without some heavy air support from their Russian friends.”

But the Russians, after a series of aerial assaults last winter on Tavildara, are keeping to their stations in Dushanbe, Qurgan-Teppa, and along the Afghan border. Nominally “multi-national,” with a few hundred troops contributed by neighboring Central Asian states, the Russian-dominated forces here proudly call themselves “kollektivnye mirotvorcheskie sily,” or “collective peace-making forces.” Although they have sewn faux U.N. blue patches onto their old Soviet uniforms, the distinction between peace-keeping and peace-making does not worry them. “The Russians are quite happy with this low intensity conflict,” said one the U.N.’s 44 military observers here, arguing that the role of peace-maker serves Moscow’s interests in the region. “Keeping things on a low boil doesn’t cost them much, and it justifies their presence.”

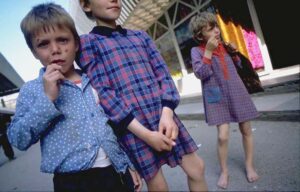

But the boil may be rising. When the World Bank has been visiting since 1993 but has yet to loan a dollar and the average Tajik salary hovers around $6 a month, the litany of complaints has grown long. Forced conscription has become the norm, as male youths are forced from city buses, village marketplaces, and university classrooms to fill the armed forces’ dwindling ranks. Even the members of the prized Presidential Guard look scrawny and weary, little more than teenagers in outsized uniforms, their belts doubled around their waists.

Last year, according to the U.N., the consequences of the war jeopardized the health of the populace residing in peaceful areas. Dushanbe is plagued by a disintegrating water system that pumps out water so brown the locals call it “coffee from the tap.” The country recently set a world record for diphtheria epidemics, with 4,455 cases recorded in 1995. After 333 died, the regime finally mobilized an army of 20,000 health workers to halt the disease’s spread. “It took quite a bit of convincing, but in the end the government realized they had no choice,’ says Johan Fogerskold, head of UNICEF’s mission in Tajikistan. “Hundreds more surely would have died.”

The government’s health workers may have halted the epidemic, but trouble elsewhere abounds on the home front.

Outside the capitol, you find few of the modern amenities of civilization, such as working hospitals and open schools. Even Dushanbe boasts little heating or hot water. Only along the short stretch downtown between the Presidential Palace and the Presidential Dacha, according to one fortunate Tajik official who resides there, “you have everything – gas, electricity, and even hot water.”

But Tajikistan does abound in fear. With the war maturing and the economy in freefall, fear plagues both sides. This is not just the soldiers’ fear of losing their lives, but of losing their patrons and perhaps even their country. “Will there be an independent Tajikistan in five years?” asks Guissou Jahangiri Jeannot, who for the past year has chronicled the regime’s record of abuse for Human Rights Watch. The answer could well be another question: “Is there an independent Tajikistan today?”

Certainly the country has the semblances of sovereignty. There is a new currency – the Tajik “rubl” instead of the Russian “ruble” – and a new Constitution, Parliament and Government. Tajikistan by now is a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States, the U.N., the OSCE, the IMF, the World Bank, and even President Clinton’s $150 million Central Asian-American Enterprise Fund. But given the bloody birth of Rakhmonov’s regime, and its dependency on Russia and its Central Asian neighbors, sovereignty has yielded little more than a soapbox for the triumphant Popular Front, and a treasure-chest for the redistribution of their war booty. Although there is less and less to gain, the battles continue because fighters are paid (and almost no one else is), because the U.N. and the O.S.C.E. do next to nothing to stop it, and because the U.S. and the rest of the West have given the Russians a free hand in their own backyard. “We’re basically doing Russia a favor,” concedes the U.N.’s Darko Shilovic. “Until Washington decides to make the buck stop in Tajikistan, there’s nothing we can really do.”

Although the evidence of the state’s bleak balance sheet mounts, the regime seems in no hurry to end the costly fighting. “The government needs this war, because they’ve lost their social base,” says Oinokhol Bobonazarova, who in prewar days headed the law faculty here. Her voice carries moral authority, having endured most of Tajikistan’s post-Soviet independence under house arrest. “What does peace mean for them?” she asks rhetorically. “It only means elections and the end of their time.”

In “Camp-I-Sakhi” in northern Afghanistan, thousands of Tajik refugees have spent four years waiting for that day to come. “Sakhi” should be no man’s land. But instead it was the site selected in late 1992 by the U.N. for the tens of thousands of Tajiks who fled the fighting in their homeland and crossed the Amu Darya river that separates Tajikistan from Afghanistan. Sakhi – which in Dari means “generous” – lies a forty-five minute drive from Mazar-i-Sharif, in the middle of a desert where camels graze by day and lizards have the run of the roads at night.

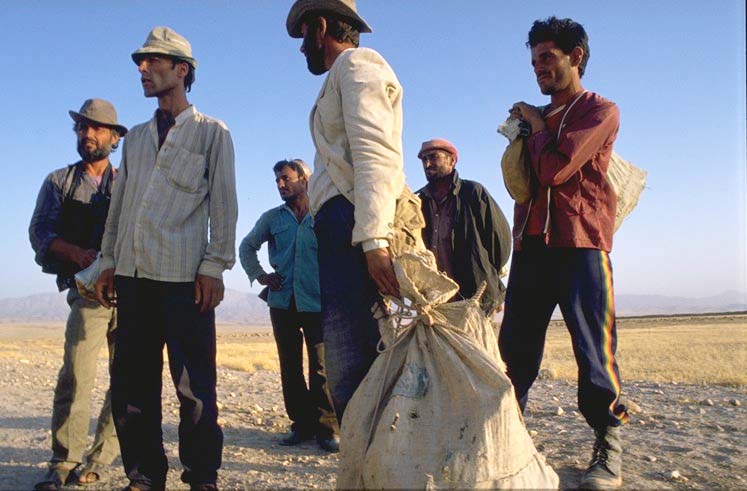

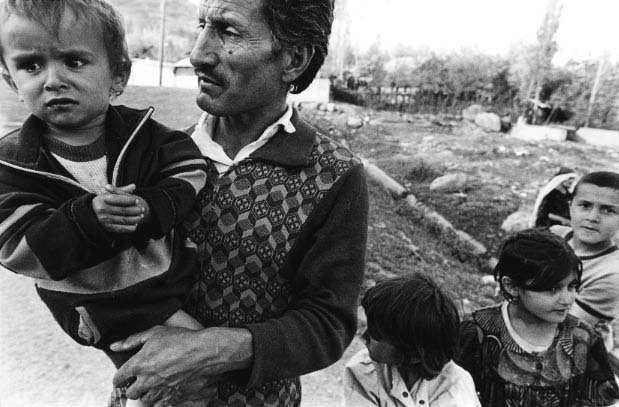

This camp once overflowed with refugees. More than 41,000 sought shelter here at the peak of the Tajik fighting in 1992. Nearly all were Gharmis. In Dushanbe, government officials routinely slip into their dominators’ vernacular when they refer to these refugees as “gorizeh,” or fugitives. After four years, their number has fallen to 7,381, according to the U.N. High Commission for Refugees (U.N.H.C.R.). In recent years, thousands were repatriated, but by June of this year, only 39 had returned to Tajikistan.

“How can we go home?” asks Hussein Tadzidinzod. His frame too lean and his beard too gray for his forty years, Hussein left a legal career in Tajikistan, but has found a new calling representing the refugees here. “I don’t know who it was, the Communists or the Fundamentalists, but somebody burned our homes.”

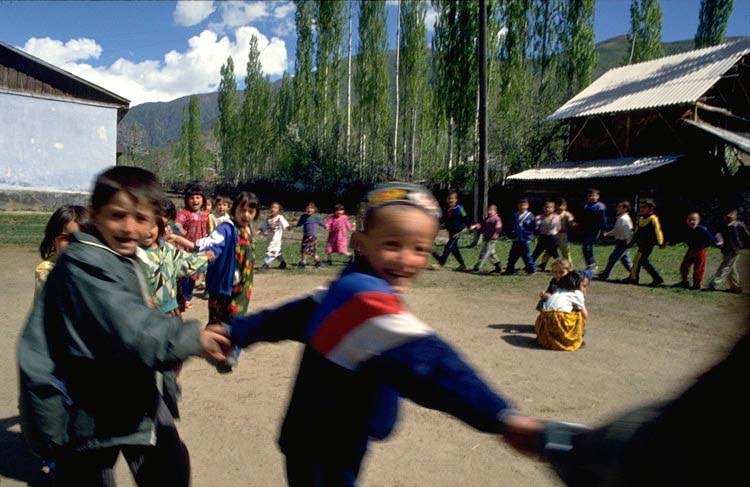

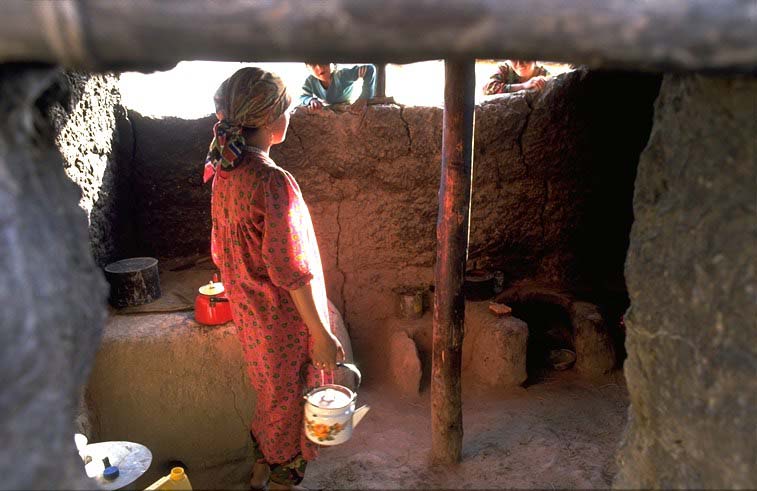

For the refugees, living in mud huts with no electricity and less and less food provided each month by the U.N.H.C.R., this barren Afghan steppe has become an inhospitable dead end. Yet in Sakhi one discovers unexpected signs of normalcy. Tajik women wearing familiar bright dresses make the national bread, lepyoshki. Children gather water from the communal pumps, while a few resourceful men tend small plots of vegetables. But no one here has settled. Their houses, one aid worker notes, were “built out of mud and in the rains dissolve back into it.

“The “hospital,” a dug-out basement ward with plastic sheeting covering its walls, is a cave for the dying. This is where mothers bring their sick babies to struggle to gain weight, to try to climb back into a life they have barely begun. On a June afternoon, eighteen are lying here, suffering from a vicious cycle of diarrhea and malnutrition. “It’s hard to say which one kills them,” says Brian Raleigh, local health director for Medecins Sans Frontieres, the Belgian group that oversees this makeshift I.C.U. “But we know that each month children will die here.”

All 18 babies are less than a year old. On Bed No. 14 sits Lola, at 17 the youngest mother here. She has come of age in Sakhi, having arrived a teenager. At 15, she married. On her lap lies her first born, Bohornadin, a six-month-old who, the doctor whispers, is not likely to survive the summer. Last year 49 children under five years old died in the camp, joining more than a thousand refugees buried among the sagebrush in the cemetery on its western edge.

The Sakhi Camp is replete with the uncomfortable paradoxes of exile. Battery-operated Russian televisions mix strangely with an overt sympathy for the armed Islamic opposition. Moreover, although food is scarce, paid work even rarer and most families boast at least six children, three or four babies are born each week. But in the midst of these suffering infants, you cannot fail to see the cost of the Tajik conflict and the mad logic of its Pyrrhic victors.

Like Hussein, most of the refugees here have had enough time to make sense of the war. Carrying in his body eighteen bits of shrapnel from the night his hometown became the front line, Hussein is fond of posing an apt question: “Why is it that in most countries, the people choose the kind of government they want, but in Tajikistan the government gets to choose the kind of people it wants?”

The question, unanswered, hangs in the dry air of the hundred-degree afternoon. It lingers around the camp, caught in the same despairing limbo as the babies dying nearby, the scared soldiers in Sicharog, the rebels in the hills, and the satraps of the regime pining for legitimacy in Dushanbe. To be Tajik, in the wake of the war, is to face a vanishing future. “The only thing we can be sure of,” says Lola without lifting her eyes from the baby wasting away in her arms, “is that there will be no end to our misery any time soon.”

©1996 Andrew Meier

Andrew Meier is a freelance journalist from San Francisco who is spending his Patterson year in the Soviet Republics.