It was in a US military helicopter going from Port-au-Prince to Hinche that I first met a representative of the Haitian justice after the return of the exiled president Jean-Bertrand Aristide was made possible by the soft-entry invasion of US troops in Haiti in September 1994.

The director of the Agency for International Development (USAID), Brian Atwood, was going on a visit to inspect programs funded by AID and – knowing the terrible state of the road to Hinche – offered a few seats on the copter to journalists and one to Monsieur Ernst Mallebranche, the new Haitian minister of Justice who wanted to solve a case pending in the Hinche tribunal.

The presence of the Minister lured me onto that trip. I hoped to have a few relaxed moments with him because I was warned that he is an extremely stiff and formal man. A conversation with the Minister at that very moment had an additional attraction for me: two days before our trip he signed a decree formally creating a Truth Commission in Haiti so I was perhaps going to be privileged and see the process of the creation of that body from its very conception.

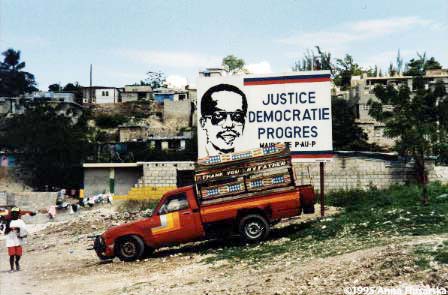

While the development programs that AID was involved in were no doubt important, the reform of the justice branch was probably the most crucial element in bringing democracy to Haiti.

“Bringing back” one may argue, but it would be not correct: the democratically elected government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide lasted less than a year and did not manage to change much in the justice system’s working. And during the exile of Aristide the cause of justice suffered a serious setback when the Minister of Justice whom he appointed, Guy Malary, was killed, gunned down on October 14, 1993 in his car near the Ministry in downtown Port-au-Prince. His chauffeur and one of his bodyguards also were killed. Malary, a young prominent Haitian attorney and political moderate, had represented several victims of military violence in their efforts to seek justice. Shortly before his assassination, Malary had presented the Parliament with a proposed law creating a civilian police force independent of military control. Then, in February 1994, Port-au-Prince Chief Prosecutor Laraque Exantus, who was named by Malary, was abducted from his home and has never been seen again. Exantus was responsible for several sensitive criminal investigations, including the Malary killing.

By the time I met Monsieur Mallebranche, who had Malary’s portrait in his cabinet, part of the late Minister’s plans were being carried out, although the credit for it does not go to the Ministry of Justice: the returned president Aristide was about to reduce the military to a small music band, a new police force was planned and interim police were being trained. But until this day the case of the assassination of Minister Malary is not solved.

There is this Haitian proverb: “Law is paper, bayonets are steel.” The Lawyers Committee for Human Rights used it as a title of their 1990 report about “The Breakdown of the Justice System in Haiti,” a document which starts by announcing: “There is no system of justice in Haiti. Even to speak of a ‘Haitian justice system’ dignifies the brutal use of force by officers and soldiers, the chaos of Haitian courtrooms and prisons, and the corruption of judges and prosecutors.” Then, for over 200 pages the report goes on to describe in sometimes gruesome details the state of lawlessness in Haiti in the four years following the downfall of the Duvalier regime.

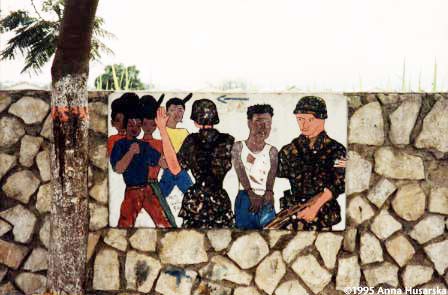

After the short-lived government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide came three years of the military junta rule (the so-called “de facto” period). The abysmal state of the Haitian justice system during that time was monitored by the joint UN/OAS civilian mission known by its acronym MICIVIH.

The MICIVIH’s human rights monitors concluded in its March 1994 report that during the military junta’s rule, the armed forces, including the army, police, rural section chiefs, attaches and members of the armed paramilitary group called FRAPH (Front pour l’avancement et le progräs haitien, Front for the Haitian Advancement and Progress) threatened, beat and sometimes killed judges, prosecutors and lawyers. Judges and prosecutors admitted to the Mission’s monitors that they were too afraid to issue arrest warrants or investigate cases involving the military, para-military groups or certain civilian supporters of the military. This was true even after the return of president Aristide.

Until this day the serious accusations (political murders in the last year of the military regime) against two leaders of FRAPH, Louis Jodel Chamblain and Emmanuel “Toto” Constant have not been followed by their arrest. The former does not intend to return from the Dominican Republic and the latter flew, according to the weekly “Haiti Observateur,” to Washington “on a visit to relatives.” Nineteen people testified against those two FRAPH-istes but it is almost certain that justice will never reach them. Part of the reason is that Haitian justice is in shambles but another, more powerful explanation is that the US may not be keen to see Toto caught: he got off the CIA’s payroll as recently as spring 1994.

The MICIVIH also reported what almost everyone in Haiti knew: that corruption and extortion were endemic to the system. Bribes are abetted, but not excused, by the abysmal salaries paid to judges, prosecutors and other judicial officers. It is common knowledge in Haiti that people pay the police to arrest a rival and that prosecutors demand payment before opening an investigation or issuing an order.

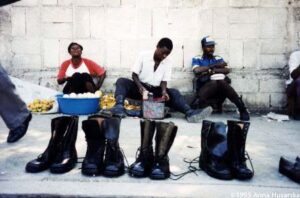

In the countryside the anarchy is such that the local sheriffs called “chefs de section” have total power over their subjects. During a visit to the Artibonite Valley in the de facto period I heard about many instances of regular extortion: the equivalent of $15 had to be paid to “chefs de section” for a wedding (the assumption being “if the peasant can afford a wedding, he can afford a bribe, too”), a pregnant woman had to pay the same, a piece of cattle killed for private consumption cost a ransom of $3, a goat or a pig was $1.50, and so on. Those were taxes not to be found in any law and they were imposed arbitrarily; those who resisted paying were threatened or arrested, so everyone paid.

Prison guards demanded payment when the family wanted to bring food to a detainee and they extorted money from prisoners under threat of beatings or tortures. When I visited Verettes in the Artibonite Valley in 1992, two common crimes were committed recently in its vicinity and a wave of arrests followed. With the pretext of conducting an investigation the “chefs de section” started a massive extortion in the area, demanding the equivalent of $10 in their local section, then sending the person to Verettes where freedom could be bought through a further payment of the equivalent of $50.

At the lowest level of the Haitian justice system is the “juge de paix” or justice of the peace who deals with civil and commercial cases and with petty misdemeanors. Those judges have often never been to a law school and have received no specialized training to be judges. Similarly, most of the higher level judges and prosecutors are very poorly trained and lack motivation. The “juge de paix” in a little village called Cazales in the mountains above Cabaret was simply the local tailor. I tried to engage him into some talk about the Haitian justice system but his knowledge was nonexistent; the local population told me that he was the best tailor in the village (He was the only one, too). I suspect that his credentials as a judge rested on similar premises.

The MICIVIH observers reported from Hinche that one of the prosecutors in this department was a school director, a dentist, he owned a pharmacy, a bookstore, a clothing store and he was a big landlord and MICIVIH commented that “his extremely limited work schedule at the Court leaves him enough time for his various non-judicial pursuits.”

The “juge de paix” whom I met in Cazales did not – of course – have anything like an office or even a desk (his old Singer machine served him all right) but higher courts in bigger agglomerations also lack even rudimentary materials necessary to function. Most have no electricity or phones, and things like copy machines, computers or faxes are unheard of. The tribunal in Hinche (a departmental capital) was a wooden one-floor structure with no electricity and no window shutters so that the whole of Hinche stands outside looking into the proceedings. The high court in Port-au-Prince had two working phone lines when I visited it (I was trying to contact the prosecutor who was handling the case of “Toto” Constant) and no operating photocopy machine.

Logistical deficiencies are only part of the problem. Material shortages are another: the basic texts (the civil and penal codes, the code of criminal procedure) are usually lacking and besides most of the proceedings are conducted in French, a language that is not understandable outside the restrained circles of elite. But the main problem is a total contempt for the rule of law, for any procedures or protections offered by the legal system. Most arrests are conducted without warrant, and resemble abductions. No registers are being kept in prisons, smaller jails or detention centers.

After the Multinational Forces (MNF) were deployed in Haiti in September 1994 they did not conduct any regular inspection of the prisons or detention centers. One counterintelligence officer from the 10th Mountain Division, Captain Lawrence P. Rockwood, impatient with his superiors’ indifference to possible human rights violations, conducted an unauthorized inspection of the National Penitentiary in Port-au-Prince and was court-martialed for doing it. The facts that emerged during his trial have brought mostly embarrassment to the conduct of the US Army. For instance, the first inspection carried out in that National Penitentiary happened exactly three months after “the immaculate invasion” as the MNF landing was called, but it also revealed a lot about the way the Haitian penitentiary system functions or rather does not function. No registers were ever kept, the prisoners did not have any attorneys and in fact, as the International Red Cross found out to its amazement, 95 percent of the inmates were not even indicted.

The other thing that I learned in all the appalling detail during the trial of Captain Rockwood were the conditions of detention in Haitian prisons. A visit by the US Special Forces to the police station in the southwestern town of Les Cayes led to an unplanned inspection of the adjacent jail. What was found was a real dungeon; 30 men forced to sleep together in one 40-by-15-foot cell. Captain Paul Lombardi from the Special Forces summed it up rather explicitly: “I’ve never seen anything like that, and I’ve been in every shit hole in the world.”

Given the ghastly state of anything vaguely related to the question of justice it is no wonder that most Haitians view lawyers, judges and virtually anyone connected with the justice system, with well-deserved scorn and contempt. The rich buy justice and the poor mistrust it. Those who can, try to resolve disputes on their own, with often disastrous results.

Like the Augean stable, the Haitian justice system needed a radical cleaning job, but Minister Mallebranche was certainly not the Hercules that was called for. When I suggested that this was perhaps a case of wrong man in the wrong place, his friends defended him by pointing out to the defects that Mr. Mallebranche had not: “He is incorruptible and he is not stupid.” I would add on the positive side that he is elegant, has a comedian’s talent and speaks a very refined French but this still did not make him fit to be a minister. The best day of his ministership was the day he left it. But precious time was lost before his successor, Jean Joseph Exhume, who used to be a legal adviser to Jean-Bertrand Aristide, started on the job.

Apart from the broad reform of the justice system which was more than overdue, the most urgent task awaiting Minister Exhume was the launching of a Truth Commission, along the lines of the one in El Salvador, Argentina, Chile or more recently South Africa. Exhume now has been replaced by René Magloire, a former member of the fledgling Truth Commission.

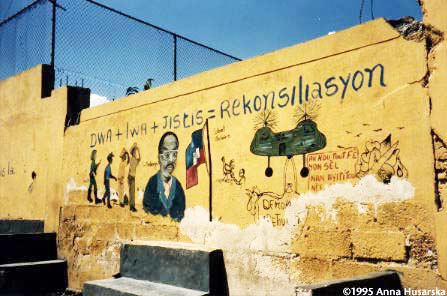

By investigating claims of human rights violations, the Commission would give Haitians a chance to testify on the abuses they experienced and its report would establish a record for later prosecutions. Such a Commission would also have an effect of catharsis. Bill O’Neill from the National Coalition for Haitian Refugees, told me that it was necessary for the national healing and as a good faith effort to try and end the cycle of impunity in Haiti.

Another foreign human rights expert working in Haiti was even more explicit: “A Truth Commission buys time by dealing with what the justice system in its present state would not be able to handleIt prevents the simple introduction of ‘victor’s justice.'”

Of course the human rights violations in Haiti and in El Salvador were different, mostly because El Salvador had a regular civil war going on for more than a decade, whereas in Haiti there has been no insurgency, no guerrillas and all the violence came from one side: the military and its paramilitary allies. Similar differences emerge in comparisons with Argentina, Chile or Uruguay, but not so much when one looks at South Africa, although there the handing over of power was a result of a bilateral effort and amnesty had a different sense. But all these and other Truth Commissions were a precious source of experience to draw on. (According to Priscilla B. Hayner, an expert in the field, there have been fifteen Truth Commissions in the world.)

Like in most other countries that went through a long period of authoritarian or totalitarian regime with extensive violations of human rights this experience there is ample knowledge in Haiti of the atrocities committed in the last three years. The number of victims is estimated at 3,000. Tens of thousands more were beaten or tortured. But a Truth Commission report would mean the acknowledgement of those crimes, which may not vindicate the reputation of the victims but would bestow at least some dignity on them.

The principle of the creation of a Truth Commission was agreed to by the Haitian Senate and it was welcomed by all human rights organizations in the country and abroad. O’Neill, of the National Coalition of Haitian Refugees drafted several option papers, made precious suggestions and offered advice. The Montreal-based International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development was asked by President Aristide in January 1994 to prepare a detailed proposal for establishing a Truth Commission. The proposal was ready by November 1, 1994.

According to this proposal, the Truth Commission’s mandate was to cover the entire period from the fall of the Duvalier family dictatorship in February 1986 through Aristide’s return to Haiti on October 15, 1994, including his seven-month tenure as president in 1991 which ended with the military coup d’etat. Three members of the Commission were to be nominated either by the UN Secretary General or by the Organization of American States, subject to Haitian government approval. The Aristide government was to name the three other commissioners, all Haitians.

On December 17, 1994, president Aristide signed a decree creating the commission and naming sociologist Francoise Boucard as its head. But the decree did not specify the concrete mandate of the Truth Commission, neither did it nominate the other members. I met Minister Mallebranche two days after he signed this very same decree and asked him about it. “Truth Commission?” His eyebrows met in a theatrical frown: he vaguely remembered that he had signed something on some such thing, but could not recall the name of the person who was nominated as head, nor could he tell anything about the prerogatives of this Commission.

This was not a good sign. The streets of Port-au-Prince were full of graffiti calling for “jistis.” But judging by the discussions I had in December both in the capital and in the countryside, Haitians were growing impatient with the lack of justice. One man in Hinche told me that in his opinion it was more dangerous not to bring justice than not to bring food, shelter or medicine to people. Another said that reconciliation was important but at least truth had to be established. I left Haiti without seeing any sign of justice being done.

I returned to Port-au-Prince in mid-April, two weeks after another presidential decree creating the Truth Commission, this one with all the members fully named, and its term limited to six months with one possible extension of three months. Now the Commission’s mandate was spelled out too, and it was decided that its work would cover only the de facto period, i.e. none of the human rights violations that occurred while Aristide was in office would be investigated. The fact that Aristide was not going to subject his own actions to scrutiny was considered among the human rights’ organizations as a mistake because it diminished the appearance of fairness.

The question of establishing the responsibility for the human rights violations – whether names would be named – was not solved in the decree. Its article 4 only says: “the Commission should try to identify the material authors and the accomplices of [serious human rights violations and crimes against humanity], their instigators and shed light on the methods and means that were used.”

To get some information on the work in progress I tried to approach the Commission but its members were not speaking to the media and they only issued a very short press release that was a simple wish-list.

My next trip to Haiti, in July, was a fiasco too and this time it was alarming. The Commission, created formally on March 28, was halfway into its existence and it was still virtually dormant as seen from outside. There were no public announcements on radio or television. In over a week of conversations with Haitians in the capital and outside it I did not encounter one single person who heard anything about the Commission’s work.

Even the nongovernmental organizations concerned with human rights did not know where exactly the Truth Commission was located. I finally learned that its headquarters were in Peguyville, a very elite quarter above Pietonville, in a former embassy of Ivory Coast and far away from the downtown area where potential witnesses live.

Having called beforehand from the States, I arranged several appointments with the Commission’s president and members with the intention of following its work. During an interview, Francoise Boucard was defensive, secretive and she denied having any problems with the Commission’s work. She said I could come to the office the next day but when I arrived she did not allow me to speak with anybody. After my insistence, she let me talk for seven minutes with one Commission member Mr. Freud Jean, and then made sure that I left the premises.

Permission to speak with future investigators, with the database specialist or indeed with anybody in the headquarters was out of question. One thing Mme. Boucard shared with me was her outrage at the journalist who wrote a negative article about her and the Commission’s activities. She said she did not know why it was so negative. I knew.

The very difficult personality of the Truth Commission’s president may account for a lot of problems, but there is much more to the whole picture. The parliamentary elections held in June (generally considered as extremely messy) are a good example of how bad logistics and lack of discipline can make serious political irregularities possible.

The Truth Commission has been reluctant to publicize its work, so halfway into its term it still had no offices apart from the headquarters, no advertisements on radio or TV and the investigators did not start taking testimonies. It appears that the way the Commission is going to publicize its existence is mainly through local grass-root development organizations and no public announcements are foreseen. This may bias the final result because the final report will indicate that the repression was more premeditated and political then it really was.

When asked why the Commission is so invisible, Ms. Boucard hints at possible security concerns, but to have a semi-clandestine truth commission defies its very purpose. One of the most prominent human rights activists in Haiti, Jean-Claude Jean, resigned in February from the provisional membership complaining of incompetence and lack of political will.

All Haitian and foreign or international human rights groups that I spoke to complained about the Truth Commission’s incompetence, slow pace and disorganization. Many of these groups have extensive files on human rights violations and those files – with proper guarantees regarding confidentiality – could be used by the Commission. Reports by MICIVIH and testimonies gathered by Lawyers Committee for Human Rights could also be used but none of these groups will let its material be used unless there are some guarantees as to the seriousness of the Commission’s work. Recently I even heard opinions that because the Truth Commission is doomed to be a failure, it is better to write it off than to tarnish one’s own credibility by cooperating with it.

There are serious problems with the financing of the Truth Commission. The UNDP gave it $80,000 of seed money but this was all what came from abroad; the rest had to be provided by the Haitian government. Canada has promised over a million Canadian dollars and United States promised $250,000, but none of this materialized. The USAID also has earmarked $18 million for a reform of the Haitian judicial system but this money is going to be paid to a U.S contractor who will carry out the task. This reform project, by the way, totally ignores the existence of the Truth Commission.

The United States government, whose role in the return of Jean-Bertrand Aristide to Haiti is undisputable, may have a more complicated role in bringing democracy back to Haiti. The links that members of FRAPH had with CIA may be only the tip of the iceberg, and the CIA (especially after the bad press it got for its involvement in Guatemala) certainly has no interest in seeing a very thorough investigation of the past state crimes and human rights violations in Haiti.

A lot depends on the Commission’s success, since this may be Haiti’s only chance to deal with the issue that matters most to many of its citizens. A fiasco of this project may deceive Haitians forever, and they may want to take justice into their hands. Partial success may not be sufficient because, given the internal divisions in the camp once united behind president Aristide, it may lead to suspicions. Violence could follow the publication of a report where only the current supporters of Aristide are presented as victims of the military junta.

Because the Haitian constitution does not allow president Aristide to run for office again, he is required to step down in December and the report of the Truth Commission must be out by then. There are many other aspects of Aristide’s government that will be taken into account in evaluating the whole period, but if he does not achieve reconciliation among Haitians, it is difficult to see who would. The president knows it. Ever since he returned, he made the slogan “No to violence, no to vengeance, yes to reconciliation, yes to justice” his mantra. But can he do it is another matter.

©1996 Anna Husarska

Anna Husarska, a staff writer of The New Yorker and a contributing editor of The New Republic, is examining the politics of memory of new democracies.