When the Guatemalan president-elect Alvaro Arzú promised on January 7 that his government “will be one of total and absolute respect for human rights,” the announcement had a novel ring to it that on second thought was rather chilling. Mr. Arzú led his rival, Adolfo Portillo of the Guatemalan Republican Front or FRG, by only 31,950 votes. Given that FRG’s founder and leader, General Efraín Ríos Montt was responsible for massacres in Indian villages during the 1980’s, Mr. Arzú’s victory allowed the human rights community to sigh with relief. But whether the new president will be able to keep his promise and bring an end to the killing of civilians depends mostly on his handling of the military.

The 35-year-old Guatemalan civil war is the longest in Latin America and also the most under-reported. The media showed interest in the country when Guatemala was the backdrop for investigations of the killing (probably CIA-directed) of U.S citizen Michael Devine and Efraín Bámaca, a guerrilla leader married to an American lawyer. But the Mayan Indians who comprise 60 percent of the country’s 10 million people and constitute the majority of the civil war’s victims hardly ever get into the headlines, unless it is as corpses.

Most of those who travel to the remote Maya lands from the U.S. are anthropologists and writers or else political tourists: covert CIA agents and more or less guilt-ridden internationalists. To get an unbiased picture of the Indians, I contacted a humanitarian group, Doctors Without Borders or Médecins sans frontiéres, (M.S.F.) who run a mission in the Guatemalan hinterlands. Soon with a small backpack, rubber boots and a reporter’s notebook, I was on the road.

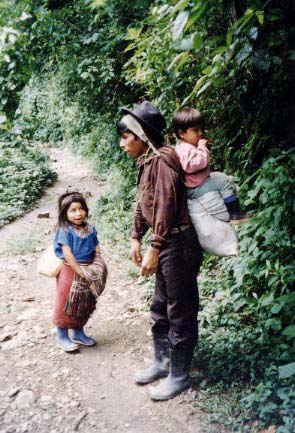

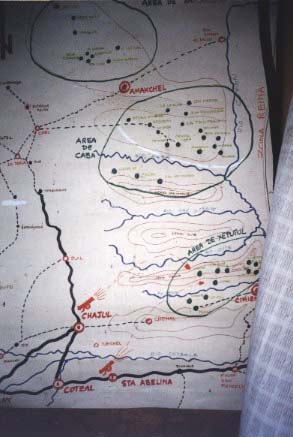

Our destination, the village of Caba, lies in the northern part of the province of Quiche. The trip is an exhausting trek up and down very steep mountains; we were jumping over streams and cutting our way through a tangled wet jungle. At times, we combatted virtual rivers of treachously boot-sucking mud, at other times we followed a path that was as wide as a foot because we were walking in a natural gutter. The air was a mild version of sauna, although during daytime, in the parts of the road where the canopy was looser, it turned into a stove.

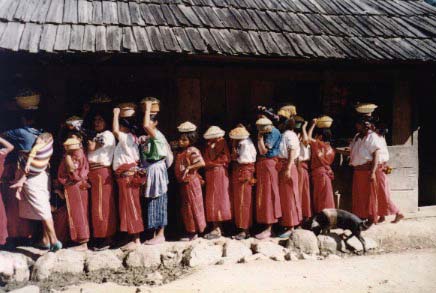

The reward for all that suffering was worth it: we traveled into the past (and into utopia). Caba, which has a population of some 6,000, looks not very different from the settlements the Spanish must have seen when they occupied Guatemala in 1524. All women wear their full traditional Ixil dress each day (very bright red skirts, and huipiles, heavily embroidered white blouses). Probably 90 percent of the teenagers have never seen a car – the wheelbarrow is the most complicated piece of mechanics they know. Cabans are all Ixil Indians save one Quiche family. In other villages the population is less homogeneous.

Looking through the diary of Isabelle, the French M.S.F. midwife, I found an entry from a village eight hours walk from Caba: “Yesterday I met the 15 women who will participate in my midwife training courses in Santa Clara. Nine of them are Ixil, six are Quiche, none speaks the other’s language, none speaks Spanish, all are illiterate.”

Caba lies in a very hilly part of Quiche. The scattered houses are mostly primitive one-room huts with barren soil for floor that smell of smoke because the fireplace is in the middle. There is no electricity or running water. Guatemala is a poor country in general, its rural areas have only basic services, but Caba is just outright primitive.

Why did these Ixils choose to live in such a remote area and in such appallingly rough conditions? They did not choose. The persecution by the Guatemalan army is responsible for the location of this and other groups of fugitive Maya Indians who call themselves Community of Population in Resistance or CPR. Because Quiche became the stronghold of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor twenty years ago, even civilians suffered from the hands of the Guatemalan army.

The worst repression happened in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when 440 villages were totally wiped off the map by the army’s policy of “scorched earth.” Approximately 100,000 civilians were killed, an additional 40,000 disappeared and more than a million people were uprooted and displaced (internally or to Mexico).

The Guatemalan army attacked from planes and helicopters, shooting the Indians, dropping bombs on them, burning their houses, killing their animals and destroying their crops, so the Ixils fled further into the jungle.

Forced to lead a nomadic and secretive life, they learned to build makeshift shelters that could be quickly dismantled. They got used to eating roots and herbs, because visible crops were being destroyed by the army, and to unsalted food, because buying salt in town was a tale-telling act.

The Indians hiding in the mountains say they were never armed and their only means of defense was posting sentinels and digging stake-pits to prevent, or at least delay, the army’s attack and to give them time to escape.

When I got to Caba it was one week after the yearly General Assembly of the CPR de la Sierra. The big letters on the roof of the community center (which consists only of that roof and its supports) read “WELCOME” flanked on the ends by two symbols not unlike a hammer-and-sickle except it was a machete-and-ax. “Where does the inspiration for this decorative motive come from?” I asked Francisco, a compañero from the Coordinating Commission, or CDC, an Ixil version of Politburo. “Oh, this? From the old Mayan culture,” he said without a wink.

Certainly the most shocking feature of Caba and all the rest of the CPR de la Sierra (total population 16,000), is a strange leftist rhetoric which sounds as you have tuned into the Spanish section of Radio Tirana, the Albanian agitprop broadcast.

All the members of CPR whom I asked denied any association with guerrillas. However, since the comrades lied to me on many other touchy questions, I have no reason to believe them. I cannot say who did most of the Marxist indoctrination – the liberation theology priests or the armed guerrilleros – but I have worked some time in Sandinista Nicaragua and I have DONE some time in Fidelista Cuban detention, so I am not completely new to the subject. Besides, the small distances and a common language make it easy for messengers to travel Central America with the leftist gospel in a khaki backpack or wrapped in a cassock.

I hasten to say that this sovietophile aura prevailing in the CPR in no way diminishes the righteousness of these people’s demands to be left in peace, the urgency of their claims for land, the suffering they endured or the savagery of the Guatemalan army that forced them to be on the run for 12 years.

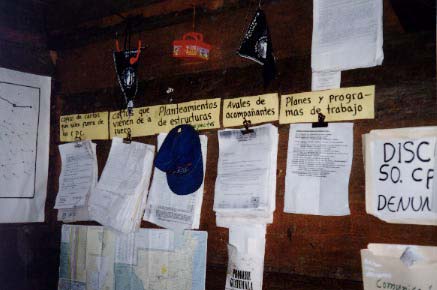

The next day after our arrival I was summoned with my passport to the CDC office. Seeing the charts of power structure in the CPR (the commissions for Projects, Education, Health, Production, Permanent Political Training and Vigilance) hanging all over, the “agent provocateur” in me immediately suggested a troubling question for the comrades from the CDC: Don’t they have a Justice Commission? “No, it is not necessary.” Oh, so they themselves decide who goes to jail for what? “No, there is no jail in CPR.” No prison? So where do the criminals go? “There are no criminals in our CPR, companera.” C’mon, every society has criminals. “Not ours,” and after a ceremonious pause Francisco added in a didactic tone: “Crimes are committed where there is no democracy, here in the CPR we have justice, so there are no crimes. Criminals, corruption, robberies – it all exists in the governmental zone, but not here, not among us.”

Most foreigners who come to Caba would probably believe him because they want to find a paradise lost. Indeed, after the CPR came out in the open and appealed for financial help, foreign solidarity groups started flocking in. Call them fellow travelers, internacionalistas. They refer to themselves as “acompañantes” because they do “acompaniment,” a sort of chaperonage, i.e. they stay with the CPRs using their cachet as foreigners to protect these Indians from the army. A few years ago there may have been a need for such protection but nowadays it appears more like boy scout games.

The acompañantes (who have names like Misha or Trocki) try to maintain the revolutionary fervor in spite of diminishing raison d’àtre. So they issue statements on the necessity of revolutionary vigilance and make bull horn broadcasts during the Sunday market conveying to the Ixils the world news that they heard on Radio Havana. At the acompañantes’ library among the statements and the Cuban radio frequencies list I found a kitschy water-colors rendition of St. Basil Church from the Red Square in Moscow dated 1994 and the inscription (in Spanish) “Seed of a red dawn in other times.” Now I suddenly became tired after my two-days’ muddy ordeal. All this effort to come across Commie apparatchiks who are indoctrinating Ixil masses in the Guatemalan jungle?

©1996 Anna Husarska

Anna Husarska, a staff writer of The New Yorker and contributing editor of The New Republic, is examining the politics of memory of new democracies.