Andrew Meier

- 1996

Fellowship Title:

- Ethnic Conflict in the Former Soviet Union

Fellowship Year:

- 1996

Report from Abkhazia

By Andrew Meier with photos by Mia Foster SUKHUMI — One afternoon not long ago in the beleaguered capital of Abkhazia, a tiny self-proclaimed republic on the Black Sea, its reigning satrap, Vladislav Ardzinba, paced his spartan office, nervously awaiting a call from Moscow. On his untidy oak desk, amidst Soviet maps and tomes on medieval Abkhaz history, sat a satellite telephone. Since the spring, when Abkhazia’s long distance lines were cut, satellites became the sole bridges to the world beyond its narrow borders. When the call finally came, half a year late, the news was good. In the Kremlin, Boris Yeltsin had at last stirred. “Bring me Ardzinba,” he instructed an aide, “…it’s time to settle this thing.” Against the backdrop of war ruins, a young widow — one of the thousands in Abkhazia — waits for a bus in Sukhumi, the capital of the self-proclaimed republic. With public transport scarce, the wait can stretch to an hour. Much of the city center, once lined with palms and oleander, now lies in rubble. Although

Independence Free Fall: The Collapse of Moldova’s Industrial Engine

Story by Andrew Meier with photographs by Mia Foster Tiraspol may be the bleakest of cities in the former Soviet Union. A gray town of some 50,000 beleaguered souls, it has not witnessed the destruction visited upon the Chechen capital, Crozny, nor the chromosomal damage that haunts the irradiated zones in nearby Belarus and Ukraine. But life in Tiraspol, the capital of the self-proclaimed “Transdniestrian Moldovan Republic” (known in its Russian initials as the “PMR”), is just as hard. When the Russians who predominate here declared their intention to break free from the former Soviet republic of Moldova, an armed conflict ensued in the summer of 1992. Five years later, life in this implausible mini-state has approached its minimalist limits. Crossing its threshold is reminiscent of entering East Berlin, circa 1980. Russian peacekeepers line up for lunch at the Transdnestria border. Since the 1992 conflict subsided, in addition to Russia’s reconstituted 14th Army based in Tiraspol, Russian and Moldovan soldiers have kept a joint watch on the border zone. Frozen in the darkest days of

The Spoils of War: Report From Nagorno-Karabakh

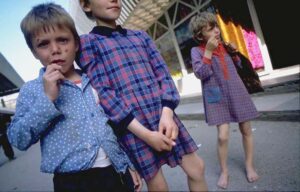

Story by Andrew Meier with photos by Jacqueline Mia Foster You’ve won the war, now win the peace.” The words come to me from an old hand in the tangled politics of the Caucasus. We are sitting in a well-appointed foreign embassy in the capitol of Armenia. My host, a western diplomat, related his prescription for Armenia’s ailments. “This is what we must tell the Armenians all the time now. The war’s over, you’ve given the Azeris a good licking, but still there is no peace. What then have you really won?” Two Azeri girls are displaced persons following the war. Stepanakert is the capitol of Nagorno-Karabakh, the disputed Armenian enclave that was within neighboring Azerbaijan on the old Soviet map. The victors of the oldest war in the former Soviet Union are at last rebuilding. After eight years of fighting for independence – first from Soviet control, then from Azerbaijan – a 1994 cease-fire is holding, and the leaders of the self-proclaimed “Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh” are patching Stepanakert’s shell-ravaged apartments and paving the craters

Report From Tajikistan

Story by Andrew Meier with photos by Mia Foster TAJIKISTAN – It had been a lovely afternoon drive through the mountain passes of this small Central Asian state. As we made our way along the craggy reaches of northeastern Tajikistan, the greatest threat had been the stretches of the dirt road that had washed away in the heavy spring rains. We had just navigated a narrow valley littered with the detritus of yet another battle in the four-year-old Tajik civil war. On a deserted field battered and burnt tanks lay scattered as monuments to an opposition victory. But the rebels had not held this ground long, and within a month they had been forced back to their perches in the surrounding mountains. Now the government forces were back in charge. The road was open and safe, it seemed, to traffic. But here along the remote roads of this beleaguered nation of 5.9 million, as in so many of the war zones of the former Soviet Union, security can be a fleeting sensation. Each checkpoint brings