David Owen

- 1984

Fellowship Title:

- Standardized Testing and American Education

Fellowship Year:

- 1984

Tempting the Medicine Freaks

The standardized multiple-choice examinations of the Educational Testing Service have been fixtures in American society for so long that we tend to take them for granted. When ETS refers to such tests as “objective,” we seldom stop to think that the term can apply only to the mechanical grading process. There’s nothing genuinely objective about an exam like the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), ETS’s biggest seller: it is written compiled, keyed, and interpreted by highly subjective human beings. The principal difference between it and a test that can’t be graded by a machine is that it leaves no room for more than one correct answer. It leaves no room, in other words, for people who don’t see eye to eye with ETS. Understanding how the test-makers think is one of the keys both to doing well on ETS tests and to penetrating the mystique in which the company cloaks its work. Despite ETS’s claims of “science” and “objectivity,” its tests are written by people who tend to think in certain predictable ways. The easiest way

Inventing The SAT

“We must face a possibility of racial admixture here that is infinitely worse than that faced by any European country today, for we are incorporating the Negro into our racial stock, while all of Europe is comparatively free from this taint.” From A Study of American Intelligence, by Carl Campbell Brigham Carl Campbell Brigham was a young professor of psychology at Princeton. His book, published by the university’s own press in 1923, was a painstaking analysis of the Army Mental Tests, which Brigham had helped administer to new recruits at the time of America’s entry into World War I. Brigham’s work with soldiers had convinced him that Catholics, Greeks, Hungarians, Italians, Jews, Poles, Russians, Turks, and–especially–Negroes were innately less intelligent than people whose ancestors were born in countries that abounded in natural blonds. In his book he argued passionately for stricter immigration laws and, within America’s borders, for an end to the “infiltration of white blood into the Negro.” “The really important steps are those looking toward the prevention of the continued propagation of defective

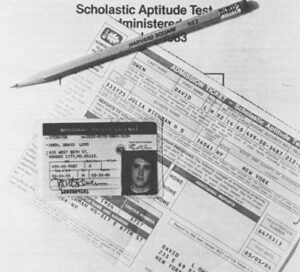

Taking The SAT

It was already evening when I suddenly remembered. I rummaged through my desk and then emptied a kitchen drawer, turning up several ambiguous candidates. Is a Woodclinched Eberhard-Faber Blackwing the same as a No. 2? My wife buys the pencils in our household, and she favors exotic leads. Suddenly gripped by an old but familiar fear, I hurried to the corner drugstore and bought a package of Harvard Squares. College-bound high school students may have guessed the reason for my moment of panic: I had signed up to take the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) the following morning, and a No. 2 is the only pencil whose mark is legible to the machines that score it. The instruction sheet I had received with my admission ticket advised me to bring two No. 2’s to the test. I sharpened four and put them beside my wallet on the bureau. The SAT–published by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) under contract with the College Entrance Examination Board–is the most important college admissions test in the United States. More than

Testing Teachers

In November of 1983, the Governor of Arkansas signed a bill requiring public school teachers to pass competency tests in order to keep their jobs. As you might expect, the new law was harshly criticized by teachers. As you might not expect, it was also criticized by the Educational Testing Service (ETS), the nation’s largest testing company and the manufacturer of the examination Arkansas originally wanted its teachers to take. “It is morally and educationally wrong,” said Gregory R. Anrig, president of ETS, “to tell someone who has been judged a satisfactory teacher for many years that passing a certain test on a certain day is necessary to keep his or her job.” Anrig said his company would no longer sell its National Teacher Examinations (NTE) to states or school boards that use the tests to determine the futures of practicing teachers. Education writers generally applauded Anrig’s announcement as an unexpected gesture from a tax-exempt $130-million company that has never been eager to acknowledge the limitations of its products (which include not only the NTE