The standardized multiple-choice examinations of the Educational Testing Service have been fixtures in American society for so long that we tend to take them for granted. When ETS refers to such tests as “objective,” we seldom stop to think that the term can apply only to the mechanical grading process. There’s nothing genuinely objective about an exam like the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), ETS’s biggest seller: it is written compiled, keyed, and interpreted by highly subjective human beings. The principal difference between it and a test that can’t be graded by a machine is that it leaves no room for more than one correct answer. It leaves no room, in other words, for people who don’t see eye to eye with ETS.

Understanding how the test-makers think is one of the keys both to doing well on ETS tests and to penetrating the mystique in which the company cloaks its work. Despite ETS’s claims of “science” and “objectivity,” its tests are written by people who tend to think in certain predictable ways. The easiest way to see this is to look at the tests themselves. Which test doesn’t really matter. How about the Achievement Test in French? Here’s an item from a recent edition:

2. Un client est assis dans un restaurant chic. Le garcon maladroit lui renverse le potage sur les genoux. Le client s’exclame:

- Vous ne pourriez pas faire attention, non?

- La soupe est delicieuse!

- Quel beau service de table!

- Je voudrais une cuiller!

My French is vestigial at best. But with the help of my wife I made this out as follows:

2. A customer is seated in a fancy restaurant. The clumsy waiter spills soup in his lap. The customer exclaims:

- You could not pay attention, no?

- The soup is delicious!

- What good service!

- I would like a spoon!

Now, (B), (C) and (D) strike me as nice, funny, sarcastic responses that come very close to being the sort of remark I would make in the situation described. A spoon, waiter, for the soup in my lap! But, of course, in taking a test like this, the student has to suppress his sometimes powerful urge to respond according to his own sense of what is right. He has to remember that the “best” answer–which is what ETS always asks for, even on math and science tests–isn’t necessarily a good answer, or even a correct one. He has to realize that the ETS answer will be something drab, humorless, and plodding–something very like (A), as indeed it is (even though, of the four choices, the only genuine exclamation–which is what the question seems to ask for–is C). Bright students sometimes have trouble on ETS tests, because they tend to see possibilities in test items that ETS’s question-writers missed. The advice traditionally given to such students is to take the test quickly and without thinking too hard.

Another way to learn about the ETS mentality is to investigate the process by which ETS writes and assembles examinations. This is difficult to do, because ETS is very secretive about its methods. Throughout its existence, the company has insisted that its work is too complex and too important to accommodate the scrutiny of outsiders. Although the company’s spokesmen frequently and vocally celebrate their commitment to “openness” and “public accountability,” their operative attitude is that the real story of testing is none of the public’s business. But with some determined digging around, even an outsider can get an idea of what goes on inside ETS’s test development office.

ETS likes to imply its test questions are written by eminent professors and carefully trained experts in whatever fields it happens to be testing. In fact, most test items, and virtually all “aptitude” items are written by ordinary company employees, or even their children. Frances Brodsky, daughter of ETS executive vice president David J. Brodsky, spent the summer after she graduated from high school writing questions for ETS tests. Writing questions requires no special academic training. Aileen L. Cramer came to ETS in 1963 after working as a juvenile probation officer and an elementary school teacher. Her first job at ETS was writing and reviewing questions for the Multi-state Bar Examination (MBE), the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE), the National Teacher Examinations (NTE), and the California Basic Educational Skills Test (CBEST). ETS occasionally runs advertisements in the company newspaper, telling secretaries and other writing employees that writing test items is a good way to earn extra money. Other item writers are brought in on a freelance basis. Former employees sometimes earn pocket money by writing questions part-time. “Student interns” from local colleges and graduate schools are also hired.

Frances Brodsky and Aileen L. Cramer, for all I know, are excellent question writers. But they aren’t the sort of people outsiders think of when they think of the people who write ETS tests. Many people, for example, assume that questions for ETS’s the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) are written by law school professors or prominent attorneys. But this is not the case.

“We would sit around and discuss,” I was told by a young man who, on the invitation of a friend at ETS, wrote questions for the LSAT while a graduate student in English at Princeton. “Say I had written a question. I would say, Well, it seems to me that I was looking for answer (A) to be the right answer, for these reasons. But then in fact people would say most of us chose answer (B), and then what we would try to do was revise the passage or the stem in some way to lead people more directly to what seemed to be the reasonable answer. It was all pretty pragmatic. It wasn’t very theoretical or anything.”

This item writer had never actually taken–or even seen–the test he helped to create, but he became fairly adept at writing questions for it. “I did quite a few,” he told me. “It’s pretty tedious. The first time it took a week or two to do ten. By the end I could do ten or twenty a day. I think we were paid fifteen dollars a question whether or not it appeared on a test.”

Every test is built by a single assembler, who arranges individual items in strict accordance with strict statistical blueprints that dictate where each item will be placed. To find out whether newly written questions conform to these requirements, ETS “pretests” all new items. One thirty-minute section of the SAT consists of untried questions that don’t count toward students’ scores. How students respond to these items determines whether they will ever be used on real SATs and, if so, how they will be arranged.

Once a test has been put together in accordance with these statistical guidelines, the assembler gives it to two or three colleagues for a review. ETS’s test reviews aren’t meant to be seen by the public. The words SECURE and E.T.S. CONFIDENTIAL are stamped in red ink at the top of every page. But the review materials for the SAT administered in May of 1982 were used as evidence in a court case, and I obtained a copy. (The test itself can be found in the College Board publication 6 SATs, beginning on page 79.)

An ETS test review doesn’t take very long. The reviewer simply answers each item, marking his choices on ordinary lined paper and making handwritten comments on any items that seem to require improvement. For example, the fourth item in the first section was an antonym problem; students are supposed to select the lettered choice that is most nearly opposite in meaning to the word in capital letters:

4. BYPASS:

-

-

- enlarge

- advance

- copy

- throw away

- go through

-

The first reviewer, identified only as “JW,” suggested substituting the word “clog” for one of the incorrect choices (called “distracters” in testing jargon), because “Perhaps clog would tempt the medicine freaks.” In other words, JW said, if the item, were worded a little differently, more future physicians might be tempted to answer it incorrectly. The assembler, Ed Curley, decided not to follow JW’s suggestion, but the comment is revealing of the level at which ETS analyzes its tests.

In ETS test reviews, the emphasis is not always on whether keyed answers are good or absolutely correct, but on whether they can be defended in the event that someone later complains. When the second test reviewer, Pamela Cruise, wondered whether answering one difficult item required “outside knowledge,” Ed Curley responded: “We must draw the line somewhere but I gave item to Sandy; she could not key–none of the terms were familiar to her. She feels that if sentence is from a legit. source, we could defend.” ETS test reviewers alternate between an American Heritage and a Webster’s dictionary, depending on which supports the answer ETS has selected. In reviewing item 44, JW wrote, “Looked fine to me but AH Dict. would suggest that matriarchy is a social system & matriarchate a state (& a gov’t system). Check Webster.” Curley did this and responded, “1st meaning of ‘matriarchy’ in Webs. is ‘matriarchate’ so item is fine.”

I’d always thought that ETS item-writers must depend heavily on dictionaries. (“I had some pause over this too, but tight by dictionary,” Curley wrote in response to a criticism of item 10 in the first section.) The diction in SAT questions is sometimes slightly off in a way that suggests the item writers are testing words they don’t actually use. (“It ain’t often you see CONVOKE!” noted JW of a word tested in one item.) SAT items also often test the third, fourth, or fifth meanings of otherwise common words, which can create confusion. In the following item from the same test, the word “decline” is used peculiarly:

17. He is an unbeliever, but he is broad-minded enough to decline the mysteries of religion without them.

-

-

- Denouncing

- understanding

- praising

- doubting

- studying

-

My Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary gives the fourth meaning of decline as “to refuse to accept.” This is more or less what ETS wants to say. But the dictionary goes on to explain that decline in this sense “implies courteous refusal esp. of offers and invitations.” This usage, and not ETS’s is the proper one. What ETS really wants here is a word like “reject.” Cruise made a similar comment in her review, but the item was not changed (“Sounds fine to me and is supported by dictionary,” wrote Curley).

It may simply be that ETS item writers don’t write very well. Here’s a sentence from a reading passage in the same test: “Yet if Anne Bradstreet is remembered today in America, it is not, correctly, as the American colonies’ first poet, but as a ‘Puritan poet,’ even though her 1650 edition is an essentially secular volume–not only not ‘Puritan,’ but not particularly Christian.” Yet if…it is not…but…even though…not only not…but not. JW pointed out that this sentence was, “very confusing.” And Cruise noted that the first question following the passage was “unnecessarily confusing cause of the negative in the stem & in the options.” Curley agreed with JW and apologized to Cruise (with a “sorry” in the margin), but neither the passage nor the question was rewritten.

The most important statistic, in terms of building new SATs, that ETS derives from pretests is called “delta.” Like virtually all ETS statistics, delta sounds more sophisticated than it is. It’s really just a fancy way of expressing the percentage of students who consider a particular item but either omit it or get it wrong. (Or, as ETS inimitably describes it, delta “is the normal deviate of the point above which lies the proportion of the area under the curve equal to the proportion of correct responses to the item.”) For all practical purposes, the SAT delta scale runs from about 5.0 to about 19.0. An item that very few students get right might have a delta of 16.8; one that many get right might have a delta of 6.3.

ETS calls delta a measure of “difficulty,” but of course its logic is circular. A question is hard to find if few people answer it correctly, easy if many do. But since delta refers to no standard beyond the item itself, it makes no distinction between difficulty and ambiguity, or between one body of subject matter and another. Nor does it distinguish between knowledge and good luck. Delta can say only that a question was answered correctly by the exact percentage of people who answered it correctly. It takes a simple piece of known information and restates it in a way that makes it seem pregnant with new significance.

ETS is almost always reluctant to change the wording of test items, or even the order of distracters, because small changes can make big differences in statistics. Substituting “reject” for “decline” in the sentence completion item discussed above could have made the item easier to answer, thus lowering its delta and throwing off the test specifications. (ETS doesn’t pursue the implications. If correcting the wording of a question changes the way it performs on the test, then some of the people now getting it wrong–or right, as the case may be–are doing so only because the question is badly written.) Making even a slight alteration in an item can necessitate a new pretest, which is expensive. Revisions are made only grudgingly, even if assembler and reviewer agree that something is wrong. “Key a bit off, but OK,” Cruise wrote in regard to one item. JW commented on another: “At pretest I would have urged another compound word or unusual distracter. However its tough enuf as is.”

Test assemblers don’t like being criticized by test reviewers. When Cruise describes item 26 as a “weak question–trivial,” Curley responded in the margin, “Poop on you!” The question stayed in the test. Curley’s most frequent remark is a mildly petulant “but OK as is,” which is scribbled after most criticisms. Assemblers invest a great deal of ego in their tests, and they don’t like to be challenged. Reviewers often try to soften their comments so the assembler won’t take umbrage. “I keyed only by elimination, but I think that was my problem,” JW wrote about item 10 in the first section. Sometimes the reviewer is nearly apologetic. “Strictly speaking (too strictly probably), doesn’t the phoenix symbolize death & rebirth rather than immortality. Item’s OK, really. It needs Scotch tape.” JW concluded this comment by drawing a little smiling face. (The item was not changed.)

The phoenix item, an analogy problem, also drew a comment from Cruise. “Well–item OK–but this reminds me of the kind of thing we used to test but don’t do much now–relates to outside knowledge–myth, lit., etc…This might be an item that critics pick on.” In ETS analogies, students are given a pair of words and asked to select another pair “that best expresses a relationship similar to that expressed in the original pair.” The item:

42. PHOENIX: IMMORTALITY:

-

-

- unicorn: cowardice

- sphinx: mystery

- salamander: speed

- ogre: wisdom

- chimera: stability

-

Cruise said she would “be more inclined to defend item if it were a delta fifteen.” The item had been rated somewhat lower (i.e. “easier”, at delta 13.2) What Cruise thought she was saying was that if the item had been more “difficult,” and thus intended for “abler” students, the ambiguity in it would have been less objectionable. But all she was really saying was that she would have been more inclined to defend the item if fewer people had answered it correctly. (Or, to put it another way, she would have thought it less ambiguous if it had been more ambiguous). This, of course, doesn’t make any sense. Cruise had forgotten the real meaning of delta and fallen victim to her own circular logic. ETS’s test developers cloak their work in scientific hocus-pocus and end-up deceiving not only us but also themselves.

Curley didn’t share Cruise’s peculiar concern. “Think we can defend,” he wrote. “Words are in dictionary, they have modern usage, and we test more specialized science vocab than this. Aren’t we willing to say that knowledge of these terms is related to success in college?”

Some items, including the following one, provide especially revealing glimpses into the ETS mentality:

15. Games and athletic contests are so intimately a part of life that they are valuable–the intensity and vitality of a given culture at any one time.

-

-

- modifiers of

- antidotes to

- exceptions to

- obstacles to

- indices of

-

“What does intensity of culture mean?” asked JW, answering, “Nothing, I suspect.” This strikes me as a comment worth pursuing, but Curley made no response. Cruise also paused at number 15: “Odd to say that games are indices of the intensity & vitality of a culture–more like intensity & mood or intensity & special interests. When I think of the vitality of a culture, I want to take a lot more than games into account.” (The “special interests” of a culture?) Curley, in a marginal note, explained that the word “vitality” was “needed to make B wrong.” He also explained why (A) was not a suitable answer: “Cuz why would you want to lessen the vitality? And if by ‘modifier’ you mean ‘changer’ or ‘qualifier’ then the word still has negative connotations.”

Ed Curley–believing that to modify something is to “lessen” it, and that change has only “negative connotations”–found this item okay-as-is and moved on to other matters. But he ought to have thrown it out. Number 15 is badly written (“given” and “at any one time” are meaningless padding; most of the other words are vague; what does it mean to be “intimately a part of life”?), and ETS’s answer is not obviously the “best” choice. “Intensity of culture,” as JW points out, is meaningless; to say that one culture is more intense than another is like saying that one animal’s biology is more intense than that of another. Curley says that the purpose of the word “vitality” is to “make B wrong,” which implies that in his mind cultural intensity is a negative quality, something for which an antidote would be desirable. If this is true, ETS’s sentence is nonsensical: vitality and intensity are terms in opposition to each other.

Chess and basketball, two games played avidly in both the United States and the Soviet Union, are not, in and of themselves, indices of anything at all about the “intensity and vitality” of these two very different cultures. Games and athletic contests are more nearly modifiers of culture than indices of it: they are part of culture (along with literature, painting, government, music, and so on), and by being part of it they change it. Whether this is “valuable” or not is a matter of opinion and surely ought not to be the basis for scoring a question on a vocabulary test. (A) strikes me as the “best” choice among five very unappealing possible answers to a badly written and ill-conceived question.

In a defense of this item (presuming ETS could be prevailed upon to make one) Ed Curley and his colleagues would haughtily imply that they had delved more deeply into its nuances than any layman could ever hope to. But the confidential test reviews prove that ETS’s testmakers are hardly the sophisticated scientists they pretend to be. Their trademarks are flabby writing, sloppy thinking, and a disturbing uncertainty about the meanings of shortish words.

Whether the SAT is culturally biased against minorities is a hardy perennial controversy at ETS. The company says it has proven statistically that the SAT is fair for all. Just to make sure, for the last few years it has used “an actual member of a minority” (as one ETS employee told me) to read every test before its published. According to an ETS flier, “Each test is reviewed to ensure that the questions reflect the multicultural nature of our society and that appropriate, positive references are made to minorities and women. Each test item is reviewed to ensure that any word, phrase, or description that may be regarded as biased, sexist, or racist is removed.”

But the actual “sensitivity review” process is much more cursory and superficial than this description implies. The minority reviewer, a company employee, simply counts the number of items that refer to each of five “population subgroups” and enters these numbers on a Test Sensitivity Review Report Form. On the verbal SAT administered in May 1982, actual minority member Beverly Whittington found seven items that mentioned women, one that mentioned black Americans, two that mentioned Hispanic Americans, none that mentioned native Americans, and four that mentioned Asian Americans (actually, she was stretching here; these particular Asian Americans were Shang Dynasty Chinese, 1766-1122 BC) Two items overlapped, so Whittington put a “12” in the box for Total Representational Items. She also commented “OK” on the exam’s test specifications, “OK” on the subgroup reference items, and “OK” on item review. She made no other remarks. ETS made Whittington take a three-day training program in “test sensitivity” before permitting her to do all of this. When her report was finished, it was stamped E.T.S. CONFIDENTIAL and SECURE. Then it was filed and forgotten.

After its sensitivity review, every SAT is passed along to what the College Board describes as a committee of “prominent specialists in educational and psychological measurement.” ETS and the Board talk publicly about the SAT Committee as though it were a sort of psychometric Supreme Court, sitting in thoughtful judgment on every question in the SAT. According to the official mythology, the SAT Committee ensures the integrity of the test by subjecting it to rigorous, independent, expert scrutiny. But in fact committee members are largely undistinguished in the measurement field. They have no real power, and ETS generally ignores their suggestions.

“They always hate to see my comments,” says Margaret Fleming, one of the committee’s ten members and a deputy superintendent in Cleveland’s public school system. “Now, we have had some showdowns about it. Sometimes they change, but I find that item writers are very pompous about their work, and they don’t like you to say anything. I am saying something, though, because I feel that maybe forty people are responsible for writing items, let’s say, for the verbal area, and why should forty people govern by chance what thousands of youngsters’ opportunities might be?”

Far fewer than forty people are involved in writing an SAT, but no matter. I asked Fleming if she thought ETS resisted her criticisms of test items.

“I do find resistance,” she said. “It’s different in mathematics, for example, where there is a hierarchy of subject matter rather agreed that one ought to know some geometrical principles or know equations and the way to handle them, and then the processes of addition, subtraction, etc. In the reading areas, the verbal area, there’s not that, you know, well-defined hierarchy of what we think it is. We do feel, though, that a person with an extensive vocabulary base, a person who is well read, generally does better in a college situation. But how one samples this preparation is what is at issue. You know, which words. Theoretically, any word that is in the English language that you could arrange in an antonym or an analogy or a sentence completion or a reading comprehension format could be tested. And I just want to make sure that youngsters have had an access to that in some way. Oh, for example, occasionally something will creep in that is not just through information in that test item; it is something based upon past experience which may be related to your social class or ethnic group, and that’s what I’m always on the lookout for. I think you ought to try to get some universal items rather than something like, say, the rules of polo. Well, who knows the rules? I don’t. Do you?”

I think she meant that good verbal tests are harder to write than good math tests–although, as she told me later, “They make more goofs on mathematics than they do on the verbal, because the verbal you can always come up with a reason.” Perhaps she meant only that language is less precise than mathematics–an opinion that would be hard to argue with under the circumstances.

I called Hammett Worthington-Smith, an associate professor of English at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania, and asked him to describe his duties on the SAT Committee.

“We review exams,” he said, “we prepare questions, we take the tests, and that type of thing.”

“You prepare questions in addition to reviewing tests?” I asked.

“Yes, we have that opportunity.”

“And do you do that?”

“Yes.”

But committee members don’t write questions for the SAT. Willie M. May, chairman of the committee and assistant principal for personnel and programming at Wendell Phillips High School in Chicago, told me in no uncertain terms that preparing questions was not one of his committee’s duties. “We are in an advisory capacity,” he said. “We don’t do any tinkering at all.”

According to the College Board’s one-paragraph “Charge to SAT Committee,” each member reviews, by mail, two tests a year. An ETS answer key is included with each test. I asked William Controvillas, a guidance counselor at Farmington High School in Farmington, Connecticut, what these reviews entailed. “Reviewing involves both verbal as well as the math,” he said. “You review the questions to make sure that the question is legible and that there aren’t any trick language aspects to it, and that it’s clear, and that you come up with the answer that you think should be gotten. You get an answer sheet and some statistics with it. If you happen to be less competent in math, you still review it for language. I tend to be more verbal.”

In the course of our conversation, Controvillas used the word “criteria” twice as a singular noun and told me that the committee reviews each test “physically” (he also seemed to be uncertain about the meaning of the word “legible”). In general, he said, he found the SAT impressive. “These are tests, of course, that are made up by professional test-makers, so in a sense what you’re doing is applying some kind of quality control. A quality control function.”

Another of the official duties of the SAT Committee (the College Board’s “charge” lists eight altogether) is “to become thoroughly familiar” with the test’s “psychometric properties.” To make this possible, ETS encloses a package of statistics with every SAT it sends out for review. Committee members–even those whose strengths, like Margaret Fleming’s and William Controvilla’s, are primarily verbal–are supposed to consult these numbers in making their reviews. The computerized “item analysis” for a single SAT runs to roughly fifty pages and contains thousands of very daunting statistical calculations, including observed deltas, equated deltas, response frequencies, P-totals, M-totals, mean criterion scores, scaled criterion scores, and biserial correlation coefficients. What committee members make of these numbers is hard to say. “Math is not my forte,” said Jeanette B. Herse, dean of admissions at Connecticut College and a recent member of the committee. But she learned a lot about psychometrics during her term. “I was really very innocent when I went on the committee about what was involved in testing,” she told me. “So that’s why I say I learned a great deal about the orderly development of tests, the kind of field work that’s done, and the resources that are used.”

The SAT Committee’s real duties have more to do with public relations than with test development. Committee members tiptoe through questions and statistics they don’t understand, flattered to have been asked to look at them in the first place, and then help spread the good word about ETS. ETS has little interest in their opinions. By the time the committee receives a test, changing it is virtually impossible. “Minor revisions can be made in questions at this stage,” says an ETS document, referring to a test-development stage prior to the one in which the committee is consulted, “but a major revision in a question makes it necessary to repretest the question in order to determine the effect of the changes on the statistical characteristics of a question.” Such revisions are almost never made. As soon as committee members have completed their busywork, the test is sent to the printer.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

The Educational Testing Service issued the following statement in response to a story by David Owen which appeared in the Fall, 1984 APF Reporter

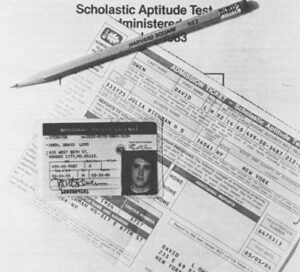

We received a letter in January, 1984, from a test candidate (David Owen) who complained about testing conditions he had endured during an SAT administration at the Julia Richman High School in Manhattan.

Whenever ETS receives a complaint about testing conditions at our test centers, it is a matter of routine policy to conduct a preliminary investigation of the test administration in question. In this case, our initial check indicated that there was sufficient cause to send an ETS test center observer to Julia Richman High School.

Our observer went to Julia Richman in May, 1984, to monitor a subsequent SAT administration, and confirmed that a number of security and administrative procedures were not being handled properly.

Immediately following the test administration, the observer met with the test center supervisor to discuss the problems and to insist that the appropriate corrective action be taken. The need for immediate corrective action was reinforced in a letter to the supervisor from ETS’s Test Center Management office in July.

A follow-up visit by an ETS observer in November revealed that no corrective action had been taken at Julia Richman, and the high school was officially canceled as an ETS test center later that same month.

ETS administers the SAT in almost 4,000 test centers nationally. These test centers are in schools or colleges and are supervised by professional personnel from the schools or colleges. We very much regret conditions like those reported by Mr. Owen, and take corrective action as soon as we learn of such conditions. Our objective is to assure that all 1.5 million students who take the SAT each year do so in settings that permit them to do their best.

David Owen replies:

ETS’s apparent concern for the security of the SAT is encouraging, but its statement is quite misleading.

ETS did indeed “conduct a preliminary investigation” in response to my letter, as I described in my article. But according to ETS’s original response to me, this investigation turned up nothing. The investigation, I was told, had determined that “all procedures were followed as outlined in the Supervisor’s Manual” and that “the instructions were in no way breached.” ETS decided to send an observer to Julia Richman only after I made a follow-up phone call and insisted that something be done.

As I described in my article, ETS’s observer at Julia Richman was apparently sent as much to observe me as to observe the test center: With several hundred seats to choose from, she sat in the desk next to mine. She also misinformed students about the proper way to take the test.

ETS finally did close down Julia Richman (though not until after my article was published, nearly a year after my original complaint), but it has done nothing about the thousands of students whose scores must now be considered suspect. Every student who took the SAT with me at Julia Richman either cheated on the test or was cheated by the proctor. And yet ETS has neither scheduled retests nor informed these students (or the schools to which they applied) that their SAT scores are invalid.

ETS’s true concern is with public relations, not test security. As I demonstrated in my article, the company knows that undetected cheating is rampant on its tests but does little about it because combating it costs a lot of money and produces unfavorable publicity. If I hadn’t pressed my complaints, and if I hadn’t been a reporter, Julia Richman would still be in operation.

© David Owen

David Owen, formerly a senior writer for Harper’s Magazine, concludes his investigation of standardized testing and American education.