James Magdanz

- 1979

Fellowship Title:

- Subsistence Living in a Changing Eskimo Village

Fellowship Year:

- 1979

Farewell to Shungnak

The Mine and the Meeting (SHUNGNAK, ALASKA) — To hear Charlie Lee tell it, it was quite a night. “Day shift, night shift, day shift, we was really working,” he remembers. “It was fall time. They was about to close down the camp. At night, after everybody go to bed, I heard a lot of shouting. I thought something was wrong down there, lots of fellows hollering. The day shift had gone off. That night shift started drilling a little, and they found copper. Boy they was really happy. Go wake up the boss. Hollering, wake up everybody in camp. The boss run around with no pants on, in his underwear. Everybody happy. That was the first they find at Bornite.” Charlie Lee is 79 now, living in the Eskimo village of Shungnak on the Kobuk River in northvvest Alaska. More than 20 years ago, he was a summer employee of Bear Creek Mining, exploring the southern flanks of the Brooks Range near Shungnak. Now a subsidiary of Kennecott Copper Corporation, Bear Creek found some

Very Expensive Education

SHUNGNAK, ALASKA – George White molds the lives of thousands of people. Millions of dollars flow across his desk. Mention of his name is sure to draw opinion, while his own opinions are sought by many. A public servant, his salary exceeds the governor’s or the U.S. Senators’. He is one of the most powerful men in this part of Alaska. His business is not oil. His business is children, Eskimo children. George White is superintendent of Northwest Arctic School District headquartered in Kotzebue, Alaska, serving 1,550 students in grades K-12 with 130 teachers and 227 aides, cooks, custodians, principals and administrators in 11 small villages scattered across 36,000 square miles of roadless Alaskan wilderness. It is an unusual operation. It spends over $6,000 annually per student, three times the national average of $1,800. It pays first year teachers $20,033 for a nine-month contract, half again the U.S. average for all teachers (but less than some rural Alaskan districts). In Shungnak Alaska, a village of 200, it built a $2.7 million school for 75 students.

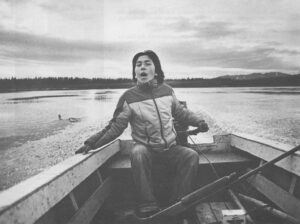

Eskimo Fish Camp

(ON THE KOBUK RIVER)-A fat chum salmon slid over the bottom of the Kobuk River, following tiny trails etched in the sand and leaving yet another trail to mark his passage. Nearby swam scores of other salmon, now silver but growing mottled pink as they left the ocean behind. Females fat with roe broke water and dove again. The shallows rippled in the long evening light as school after school surged upriver. Three Eskimo boys eyed the current where the salmon passed. On a long sandbar behind them stood two white canvas wall tents. A fire burned slowly under a black iron pot of beaver stew. A dozen paces downwind stood long wooden racks heavy with cut and drying fish. This is the middle of the vast Alaskan wilderness, north of the Arctic Circle and hundreds of air miles from Fairbanks or Anchorage. A map shows no roads, but charts instead huge parks, mineral deposits and five small Eskimo villages with a population of slightly more than a thousand. While America debates the fate of

Spoiling the Blueberry Patch

(SHUNGNAK, ALASKA) – The road to the new sewage lagoon runs through a blueberry patch. It’s a small matter. An acre of blueberries was traded for easy access to the lagoon and, coincidentally, to the rest of the blueberries. On a windy day this summer, you could often find village women and children hiking out the new road to gather wild berries for the winter. When their baskets were full, the road carried them home again to Shungnak, past the new school, past the telephone and television satellite dish, past the water and sewer plant and finally home to a new plywood and frame house. Supper was soon readyfresh moose and pilot bread, hot tea and wild berries with seal oil and sugar. “If I were around when they were trying to put the sewer near the blueberry patch,” said Jenny Norris, the young Shungnak city administrator, “I would have been against getting the water and the sewer. “But people didn’t reallv think about what they were getting into. They didn’t realize what the costs

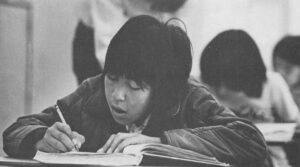

Eighth Grade Eskimo

(SHUNGNAK, ALASKA) – “We are going out hunting tonight, hunting muskrats, beaver, whatever. You want to?” Jamie Commack sat up in a makeshift canvas tent in front of his parent’s cabin. “Let’s go ask Greg if we can use our boat.” Jamie Commack “Take 30-30,” suggested Vernon Douglas, crawling out of the tent after Jamie. “Yeah, 30-30, 30-40,” he laughed. Jamie walked quickly toward the cabin. “Let’s go get ready, Niqi,” using Vernon’s Eskimo name. Jamie and Vernon are Eskimos, just completing the eighth grade in Shungnak, Alaska. Jamie is the youngest son of James and Buelah Commack. James is mayor of Shungnak; Buelah is school cook. Vernon is the son of Vera and Leonard Douglas, local Alaska Fish and Game Department representatives. Today, Jamie and Vernon are hunters. Preparing for the Hunt In the cabin, they went over their arsenal. “Think that shell will come out?” Jamie asked, holding up a lever-action 30-30 rifle for inspection. “We might get some caribou. Try see…” A cartridge was half in and half out of the breech,