Kay Mills

- 1995

Fellowship Title:

- Faces of Head Start

Fellowship Year:

- 1995

Indian Head Start: Restoring a Culture

HARLEM, Montana – Winston Morin pulls the Head Start bus up to a pink quonset-hut classroom at the Fort Belknap Agency and joshes with teacher Barbara Long Knife as she climbs aboard for the late-morning ride. The two-way radio hanging above Morin’s left hand crackles briefly to let him know that one of the children on his route won’t need a ride this chilly morning. The bus rolls out beyond the tribe-run Kwik Stop and its gift shop onto the main road on this north central Montana Indian reservation. Winston Morin drops off his charges after the morning bus run. Transportation is a major expense for Fort Belknap’s Head Start program. The ride is my introduction to a handful of the children served by 121 Indian Head Start programs in 28 states. The 168 three-and-four-year-olds enrolled at Fort Belknap and the other Indian children nationwide make up only 4 percent of Head Start’s total, but their needs dramatically illustrate not only the impact of this federal program but also some of its problems. Indian Head

Head Start: Helping Alabama’s Poor Survive

Question: Which of these activities involves Head Start? A woman sets as her goal obtaining a commercial bus driver’s license, succeeds, and then aims at a new target- taking the test for her high school equivalency diploma. A child sees commitment to service in adults around him and ultimately decides to join the Peace Corps. A woman who had dropped out of school in the eighth grade nonetheless has a yearning for more education, earns a high school diploma, then completes bachelor’s and master’s degrees. A family can’t pay its rent or buy food because someone got sick and there was no health insurance. They call a federally-financed community services program seeking help. Thirty-six families move into new two- and three-bedroom apartments on the edge of a university town. Twin girls have their height and weight checked and wince as they have blood drawn so that it can be tested for lead and iron levels. The answer, in Lee County, Alabama, is “all of the above.” Marian Wright Edelman (far right) cuts the ribbon opening

Migrant Head Start: Following the Seasons of the Soil

WESTLEY, California – Just as farmwork has changed, so has care for children of those who work in America’s fields. Head Start, for migrant farmworkers’ children, follows their parents’ seasons on the soil. A father weary after a day in the fields picks up his daughter at the Walter Thompson Center in Ceres, just outside Modesto, California. Head Start centers for the children of migrant farm workers care for children from six weeks old to school age. They operate seasonally and open before dawn each workday. Farmworkers often move less frequently today because they have better housing (better, but not always good). They no longer have to take their youngsters into the fields or leave them in their cars, under a shade tree where possible. Now they start arriving at 5 a.m. at the Head Start program in the migrant housing camp at Westley in the rural San Joaquin Valley, or at scores of other centers wherever crops are being picked. Across the country, for example, parents drop their children at the Head Start at

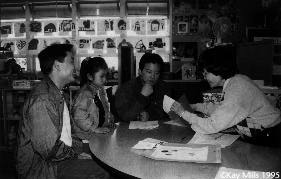

Head Start: Keeping The Edge

SAN JOSE–Tin Hout sits in one of the pint-sized chairs in which parents inevitably find themselves when they confer with their child’s kindergarten teacher. His five-year-old daughter Marina stands shyly, but attentively, beside him as Santee School teacher Margie Oyama reports that the child is progressing well. Marina, who attended Head Start last year, can count almost to 30, knows her colors, recognizes shapes. Against a backdrop of children’s artwork, Santee School kindergarten teacher Margie Oyama (right) tell Tin Hour, his daughter Marina and head Start transition project family advocate Nisseth Sath how well Marina is progressing. There is one more person in what would otherwise be a typical parent-conference picture. Nisseth Sath, a refugee from Cambodia like many of the families he helps, is translating Oyama’s report into the Khmer language that Marina’s father speaks. Sath telephones many of the parents to schedule these conferences, helps families negotiate government bureaucracies, and sometimes transports people to doctors’ appointments. His job is called “family advocate,” a key part of a nationwide pilot project to ease children’s